By Taisa Batkina (Pine)

Part eleven

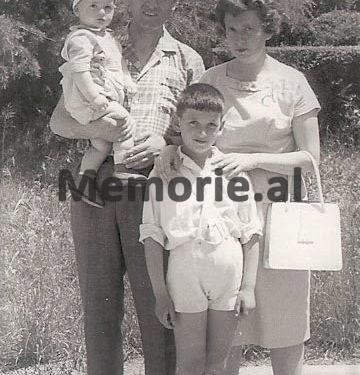

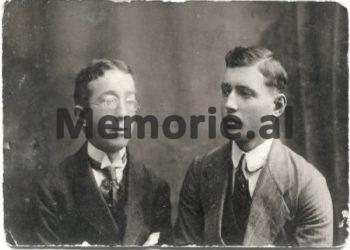

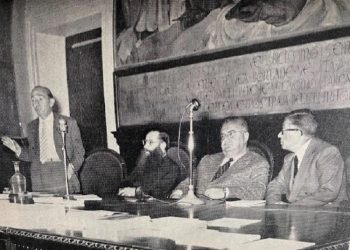

Memorie.al/ publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was orphaned at a very young age, after her father lost her life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, and began life in the city of Tirana, where Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkina on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to 16 years in political prison, which she suffered. in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a book of memories. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because we… fell in love! And let no one ever forget what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Continued from the previous issue

It had to be helped

With that amount I bought everything Natasha needed, and I decided to try to give the money to my children when they came to meet me. And suddenly… control! I had hidden the money well in the food suitcase. We were waiting in the yard. The control lasted for 3 hours. There were no more than 70-75 of us in the corps and we had very few of our belongings, but they left nothing unturned. They called them all in turn and gave each one his own belongings. My turn was not coming. Out of impatience I did not know what to do, just grazing up and down the yard, because not only would they take my money, but for a long time they could take away my right to meetings, or packages from home, or put me in jail for a few days. They finally called me, gave me my suitcase and bag. What a joy that they did not find the money! It wasn’t any big deal, but for there in prison, with that extreme poverty, you could call it pretty. With that money you can buy food for a month or two, as a supplement to the camp ration. Even the dungeon…! Luckily, I escaped this time, because those who stayed there for a while, as soon as they came out, were sent straight to the infirmary with a cold, lungs or something else. With that 500All I bought 5 meters of white sheet material and gave it to my poor husband and children.

What did we eat?

Common conditions in prison were considered the existence of half-starved man, insufficient food, but also hunger. The conditions they gave us in prison during the investigation cannot be described. Water, where a little rice, a little pasta, blackened spinach leaves, pieces of onion were boiled at the same time – all without a drop of fat! You can eat such a liquid only after a few days of hunger. Such “soup” was given to us at lunch and dinner, and in the morning only thin tea, almost without sugar and bread, a few pieces of gray bread, not well baked. In the camp it was something better, though the rate for those who did not work was the same as that of the prison, except that it was cooked normally. In the morning very thin rice soup, at lunch pasta or vegetable juice, or beans. Beans were the best food. For dinner tea Without the help of the people of the house, without work, man very quickly became like a shadow. This did not last for days or months, but for years. Every day without normal food, without what the body needs. And everyone fit in as best they could. I have often repeated the word “steal”. This was a necessary theft, a theft to escape. It was food to help survive, to give strength. Everything was made just for daily bread. There we were convinced of the wisdom of the word of the people: “God give you the day, God gives you food.” Think for a moment: in the suitcase, where he holds food, there is nothing; You have nothing to eat except the juice of the prison soup! And suddenly a small niche opens, where they share either a little excess spirulina, or a piece of leek, or some tomato seed from the garden. Someone might even bring you a bite of bread. If the neighbor next door to you at the canteen has had an appointment, she can entertain you, or give you her own lunch ration. But we also brought what we could from the field, or from the garden. When a large truck loaded with potatoes entered the camp grounds, we mingled with the unloaders, carrying heavy sacks on our backs to the warehouse on the third floor. For this work we were given some potatoes, and on the way we put some in our pockets or breasts; for themselves and for the elders, who had no power for such work.

We did not hate any work; we had to work to survive. We had a kitchen for our own use, we had built it ourselves, and before that we cooked and boiled water on the fire that was lit in the camp yard. In the evening, when we lit a fire, the camp resembled a tribe of gypsies in the campsite. In the kitchen there were small stoves, working with wood or sparks. But the chimney did not draw well, all the smoke remained inside and did not come out of the chimney, but from the roof, the door and the windows. In rainy weather you cannot stay there more than 2-3 minutes. It was there like in a hut without a chimney, you could not see anything in the distance of the outstretched arm. But we had no choice but to boil water or cook something. There was no hot water or showers in the camp; we bathed in the tub. To make life a little easier, women were connected to each other by two or three. These connections were made and broken again. At their core were friendly relations, but more often economic convenience. Vola and I remained close friends for years. Once a friend of Vola’s brought us a bag of pasta. The pasta was stale and had a long nose (insect that enters the pasta). What should we do? Shall we throw them away? But they were food, eat. And we made it up! We soaked the pasta in water and from there we took out the long noses with a spoon (colossal work), and with the dough we made crepes or pancakes. We ate them all and… we were not poisoned, we did not get sick! In a small airtight canister we salted onions, sometimes peppers, but more often leeks, which we always found in bulk in the camp garden. In Albania leeks grow well, in autumn and winter. When we opened the jar with salted leeks, it smelled so bad that we would go out in the yard, open it there and wait for the wind to blow. But the leeks itself was very tasty. All the women liked our pickle.

One day we were waiting for the clothes to dry. From there you could see the canteen, where they were sharing lunch. Next to me was Mrika, a villager from the north. She had been a nun and had served with a Catholic priest all her life. When the priest was arrested, the maid was also sentenced to 10 years in prison. Nobody came to him, nobody helped him, he lived only on what he earned by working in the field. Suddenly Mrika turned to me: “Look, what lunch, soup with meat”! We left our clothes and hurried downstairs. But i complete disappointment! It happened to us from afar that it was meat, but they were pieces of boiled eggplant, something that could not be eaten. We did not enter the canteen at all, we went back to the washed clothes. No one rides such a lunch…! On holidays, if we had something in our luggage, we would make up a festive table. Usually in a common pot we boiled water with flour, which we then emptied into crumbled bread. If there was even a little sunflower oil, to throw on…! On holidays, we often invited friends who had no one. We helped them as much as we could. We celebrated our birthdays, but also the birthdays of people close to us. We tried to cook something delicious and if we had the opportunity we also entertained our friends. One day we found at the end of a wheat field, a whole plot of barley. We gathered it, tasted it, roasted it, ground it, and for quite some time drank delicious barley coffee; we also entertained friends. Thoughts about home did not leave us alone. We knew how bad our families were, that they too were not satisfied with bread that no one cared for them. We all tried to save from what we had and from what they brought us from home. We prepared something delicious and sent it home. This was allowed.

Nina always made cookies and brought them with her before they came to the dating site. The sunflower seeds, which we brought from the fields, we hardly touched. We cleaned them, sweetened them and gave them to our family when they came to the meeting. I knew my husband liked it very much, so I tried to get it ready before the boys came. What else could we do for them? In the camp we had a small shop. If you had money, you could buy sugar, vegetable oil, pasta, cigarettes, and sometimes farm fruit. The oil was brought in glass bottles, but we had to empty it into plastic bottles. We had to return the glass bottles washed. It was great work. We emptied the last drop of oil from all the bottles onte we managed to collect another liter of oil. This was also as a reward for washing the bottles. Over time the assortments of goods in the store became impoverished. Ordinary people cursed the saleswoman, looking for food. We did not know what was going on behind the barbed wire, we did not know that most of the food was rationed all over the place; we did not know that instead everything had taken a downturn. At that time we just needed food.

Daily life and worries

In the camp we were constantly tense not only from the controls. At any moment they could invent something, where to be caught, to stop something from us, to take it from us. Suddenly we were stopped from bringing firewood from the field to sick and elderly women who could not leave the camp grounds. But wood was needed, without them you could not do. We had to bring them in secret, but that was risky work. Once the guard, whom we called a good man, caught Natasha with hidden sticks, took her and wanted to put her in the dungeon, but she changed her mind and stopped the next meeting. Natasha was waiting for the girl to come. There was no opportunity to notify him. There were very few telephones in Albania, the letters came too late. Natasha begged to be forgiven, to allow her to meet. But our new bosses upheld the punishment. The girl, who had walked so many miles through the rain and mud, was not allowed to meet her mother. Suddenly they gave us a new order: in the toilets and sinks, which were quite far away, at the other end of the hull, we now had to go in groups of 2-3 people, neither less nor more. We did not understand why; the toilets were large, there was plenty of room. The poor old women (there were many in the camp) trembled at night, waiting for one of the neighbors to wake up. In the morning we gathered from 2-3, we waited in the corner of the corridor, we stood in line…! To cry, and to laugh…! The road to the toilet passed near the command and they strictly followed that the order was strictly carried out. Those who disobeyed the order were sent back, or punished. The order was later canceled. No one understood the meaning of this order. Surely, they just wanted to make fun of us. Both in the prison cells and in the camp, the light did not go out at night. The lanterns and projectors at the top of the watchtowers drove all the stars from the sky. There seemed to be nothing left but the camp, the lanterns, and the barbed wire.

There seemed to be nothing left but the camp, the lanterns, and the barbed wire. On those rare days, when there was a power outage and there was no light in the camp, we rejoiced. We slept in the dark, our eyes were not killed, we relaxed from the electric light. In the courtyard the high starry sky was clearly visible. Such breakdowns occurred because the village wires were old, everything (as everywhere) was done anyway. But this happiness did not last long; they brought a generator to the camp and since then there have been no nights without lights. We had no right to keep hours; we were isolated and did not need to know what time it was. It was said that the bosses knew the time for us. But very soon our internal biological clocks became so accurate that they erred only 5 or 10 minutes, no more. There were many women in the camp who smoked; in our corps more than half. The canteen, where we stayed after dinner tea, had to be painted with lime every 2 weeks, as it was darkened by tobacco smoke. Cigarettes were always in short supply. They did not suffer only what people came to them in meetings. And smokers, who had no outside help, would be sorry to see them run out of cigarettes. When they worked across the wires, Nadja and I would collect cigarette butts and give them to Inga, who had no cigarettes, and that would torture her.

Appeal! A sacred word!

To the guards the man was more expensive than gold. If a missing head came out beyond the wire fence, you would put your head there! The appeal was made three times a day. All those who were in the camp were lined up outside, and the sick were taken out, only those who could not move were counted inside the corps. How many times did the appeal happen to be repeated, to err, to count and recount, to send messengers to the fields, to the brigades! There was no escape here. Albania is a small country, and then it was completely closed. Where to enter? Everyone knows each other, a spy would be found immediately, and he would report, catch you, retry you and extend your prison term. The “internship” convicts showed that once upon a time, in the 60’s, when there were few women prisoners and the regime was not so strict, three young girls saw that the guard forgot to close the gate, went out and went to the nearest town. As long as they roamed and went by themselves, they were handed over to the Department of Internal Affairs. “We wanted to show how brave we are,” said the girls, “and that there are no guards in the camp.” They returned them, brought them back to court and increased their sentence.

Life was not so bad in the camp at that time; prisoners were sometimes taken to cinemas, allowed to take pictures, and even given leave for several days on special occasions. They later enraged the prison regime and revoked all privileges. In the men’s camps the regime was extremely severe; nor was it compared to that of women. The prisoners worked mainly in the chrome and copper mines in extremely, very harsh conditions. Once in one of the camps the prisoners refused to go to work and demanded the implementation of the rules of technical security and prison regulations. The protest was brutally suppressed. Mehmet Shehu, the then prime minister who came to the camp, shot without investigation and without trial many prisoners in the camp yard, others received additional sentences. In all the camps the conditions became more severe, the requirements stricter. At this time in the women’s camp, such a case occurred. Some girls got together in the camp dungeon (it seems to me that something had been stolen, or beaten between them, it was not a serious crime). To their chagrin, they brought to the camp that evening the car with the film camera and a tape recorder with dancing music. It was thought to be a pleasant evening. The girls started knocking on the door, trying to get them out of the dungeon. But they were not released. The dungeon was located in an old building; one of the walls was made of adobe. The girls decided to wet it and tear down that wall. They threw water at him. They could not demolish it, but the noise was heard and their efforts were hailed as an escape attempt. Although many witnesses came forward, that there was no attempt to escape, and the adobe wall protruded inside the camp territories, they made the problem big, also because the event coincided in time with the rebellion in the men’s camp. The young girls were sentenced to between 8 and 15 years (the term of all of them had been 1 or 2 years). All serve the new sentence one by one.

I told you something above about the reports in Albania and how they were encouraged by the government. From the first day, when I came to the camp, I was warned: “Shut up”! And mentioned to me the most dangerous spies. In the camp we were more silent, we did not allow ourselves any conversation, which could be misinterpreted. And yet the flow of reports did not end! A report was made about everything: he did not do it like that, he did not walk properly, and he looked crooked…! And, of course, more often than not: “You did not say that.” There we were in each other’s eyes from morning to evening and everyone seemed to be in a confrontation with the persistent gaze of the collective, which continued for years. If you suppress the thought that you will never be able to be alone. When we were brought to the camp after a year and a half of investigation, behind the prison, where the grave silence reigned in the corridors, it seemed to us as if we had fallen into hell. In the canteen, where we stayed after work, there was a terrible noise. They all spoke loudly, screaming, cursing, and sometimes beating. We stood as if stunned by the noise, with our ears plugged with our fingers and not raising our heads. But in time we learned that if we did not meet, we would no longer hear the noise, as if it were not. We sat, we thought about our worries, we read, we talked to each other. And the noise was beyond the reach of obedience, outside of us. This helped us to maintain strength and nerves.

Moral support

“You can turn a man away from you,” Solzhenitsyn said in the voice of Ivan Denisovic. They returned us as they wished. Almost all of us had higher education, all of them had in freedom years of responsible work, honest work in Albania. But no one wanted to know about it now. To justify the policy of violence, enemies had to be found. And so it was. The order came from above for so many arrested and… so! They made us both spies and enemies and pushed us inside. But in spite of it all, we found the strength not to lose our sense of self-worth, to preserve ourselves. When they took us to the camp, some of our friends were waiting for us there, who had already lived in prison for 1 or 2 years. Our arrest was for everyone just a disaster.

But the misfortune can also be explained, and this was something terrible, inexplicable, black, where fate threw us. And in these conditions he had to survive. We all knew this well and rejoiced in the fact that we were so many. We realized that together we would overcome any evil more easily. They all wanted to entertain us with something, to arrange us as best they could, to tell us about life in the camp. I remember the poor Lady, whom no one came to; she hurried to treat us to something delicious. This touched us deeply in the soul. Then, we all sat together on the second floor beds and started singing our songs and marches. It seems to me that the “March of the tankers”… or something else, I remember well. Our window was on the command side and we wanted to show those who could not break us. Maybe, that was funny, but lo and behold these songs made us feel more relieved. Prison, camp, our position… all of these seemed to oppress us, we were constantly in a state of stress. This was hard to bear, very hard. We needed an “air hole”. I was thinking about what to do, how to ease our situation a little bit. And I decided to come up with a nice surprise for New Year’s Eve: write and perform hilarious beats and come up with funny gifts. At first I wanted to do everything myself, so that it would be a surprise to everyone else. I was writing at night, in the semi-darkness of the downstairs. A Romanian woman, sleeping next to me, was surprised and asked me what I was writing. But I soon realized that I just could not do it, that I needed help. I told Inga my idea, she gladly accepted and we both wrote a few verses. They gave you hope with the kindness and humor they carried. I’m very sorry, but I could not memorize those hilarious verses, due to occasional checks.

On New Year’s Eve I was adorned with furs and headdresses, which we found among the prisoners, with a lock of my gray hair making me a beard and mustache. I find it difficult to judge my costume, but my appearance on stage was accompanied by Homeric laughter. I took off my hat, put a handkerchief on my head and sang fictional verses, distributed comic gifts. The laughter of our room was heard throughout the barracks. They wanted to open our door by force, to enter, but we did not accept anyone. This was our evening, though the watchful eye of the command was always felt near. In the room we had Qerima, whom the command had assigned to us as Nadja’s close partner. This evening charged us well with optimism for a while. I liked my idea. After a year we organized such an evening again, which we all prepared together. This time we played an entire theatrical piece. Ina Shahe, the most cheerful woman among us, played the New Year old man. Nina Borëbardhë, and I was given the role of Borëbardhë’s older sister, an old abandoner who, out of grief, wanders in the forest and sings mood. I again sang hilarious mood, which we had invented together with Inga. We also made gifts together; we could not afford to buy, so we did everything with our own hands. I remember some of the gifts. We gave Nadia, who had a furry cat, a portrait of her. Nadja liked it very much and put it at the head of the bed. A few days later one of the guards removed him; not allowed! We gave Lusja, who used to close her suitcase very anxiously, a large paper key, which she held in her hand for a long time. We gave Vola a big bag. She used to take and store whatever she could find. We took the bag from someone temporarily and had to return it, which upset Vola very much. And again we got a good dose of energy. This was the weapon with which we could somehow counteract the hard life of the camp, the constant humiliation, working outside our powers, existence in a state of semi-starvation, barbed wire and armed guards, inseparable anxiety, fear for families ours.

Many of us were completely separated for years with family. In Oleg Volkov’s book “Diving in the Dark”, he finds such words: “Say what you want, but man is a creature capable of enduring any circumstance; he adapts, reconciles, and or survives where every 66 four-limbed creature, or winged creature, and even insect would die! Should we be proud of that? ” These words, like rare others, fit our life in the camp. We organized the concert next year as well. This time we announced a competition for the best number. Nadja amazingly sang some arias from the operetta, Inga recited poems, Valja sang, someone danced, another performed satirical songs. Vola and Natasha and I composed such a number: we sat down on a long, low bench and sang the song “We are going to distant lands”, with lyrics composed with prison themes. With him we unanimously deserved the first place. This was our last concert. They brought television to the camp, first to the corps of ordinary people, then to us; black and white TV, with small screen. They put him in the canteen and we could watch the Albanian Radio-Television, which worked four hours a day. Watching the latest news was mandatory. This was called part of the educational work. We watched movies, children’s shows, concerts…! So we wasted our time and had fun. The spies fanatically guarded so that no one approached the TV, remembering that someone would try to catch “foreign voices” on the TV. They did not know that without the antenna and auxiliary equipment you could not see other than Tirana, however, after their reports, they put the TV in a box, which was locked with a padlock. /Memorie.al

The next issue follows