Memorie.al / For people who have made a special contribution and achieved notable results in certain scientific fields, merely writing about them is not enough. Their work becomes the object of research and study, in various forms. A personality of the first rank in Albano logical sciences, without a doubt, was Ramadan Sokoli.

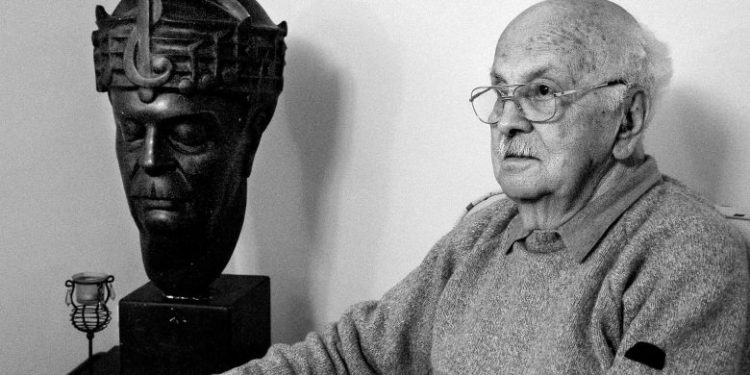

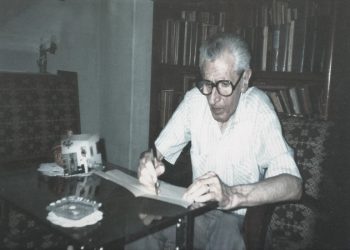

From the 1960s (when I was a student at the Academy of Music in Belgrade), I had become acquainted with and consulted two of Ramadan Sokoli’s works: “Albanian Musical Folklore” and “Musical Instruments of the Albanian People.” Subsequently, I gradually continued to get to know his entire body of work. But our first physical meeting took place in Tirana, in September 1995, in his famous apartment, the “museum-basement.”

I had traveled there as a member of the jury for the National Folkloric Festival, which that year was held in Berat. From that meeting, our ties became very close, both professionally and friendly. Ramadan Sokoli’s biography has been portrayed (carried from writer to writer) dozens of times in dedicated articles, presentations, and finally, a special monograph was also written dedicated to his life and work.

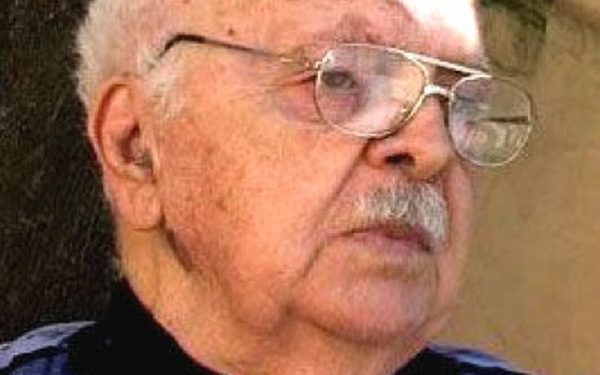

Therefore, in short, we can say that he had a life that was not very favorable, not very comfortable, but despite the circumstances that were created for him, he did great work. In a word, an unusual man, in terms of patience and responsibility, for the work he did and which he continued to do until the very last moments of his life. On this occasion, we are providing a brief overview of Ramadan Sokoli’s biography.

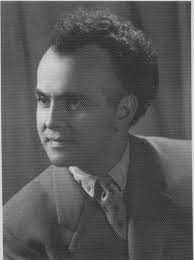

He was born on June 14, 1920, in the city of Shkodër. He belonged to a wealthy, yet always patriotic, family from generation to generation. He is the grandson of the legendary general of the League of Prizren, Hodo Beg Sokoli. His family seemed to have sworn not to be at peace under any regime. At a still-tender age, he began to play musical instruments, and from the age of 16-17, he also started composing songs in a folk spirit.

In Ramadan’s early youth, his family was interned in Italy, and there, from 1940-1943, he studied composition and flute in Florence. The socialist regime was not at all favorable to the Sokoli family. They imprisoned his brothers, and they also imprisoned Ramadan himself, from 1946-1950. During his time in prison, he gained great life experience. There, he met people from various social strata and also gained knowledge about popular culture.

After his release from prison, Ramadan Sokoli’s life in the new socialist Albania would be restricted, and within the circumstances that were created for him, with his entire spiritual and physical being, he dedicated himself to work, and only to work. The musical knowledge he had acquired in Italy, as well as his great interest in learning even more from all fields of music and knowledge in general, oriented him toward the path of research and study of ethno-cultural heritage.

In 1952, he came from Shkodër to Tirana, where he would spend his turbulent life. He was dismissed from two or three places of employment without concrete justification. Finally, he became a teacher at the “Jordan Misja” Artistic Lyceum in Tirana, where his interest and commitment to the entire Albanian ethnomusical wealth intensified. Later, he also taught at the Higher Institute of Arts (today the Academy of Arts), lecturing on several subjects, especially musical folklore and the flute.

Having spent a life under a totalitarian system, where his every movement was restricted, it is astonishing how this man managed to undertake all that research and scholarly work. Within these few lines of his biography, there are about one thousand bibliographic units, musical creations, articles, studies, monographs, and dozens of participations in forums, sessions, and scientific congresses in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and various European centers.

Right from the start, it must be said that Ramadan Sokoli, with his work in the field of musical sciences, particularly in ethnomusicology, has placed himself among the ranks of European ethnomusicologists who affirmed their national ethnomusical values, such as: Cjetko Rihtman from Bosnia, Vinko Žganec from Croatia, Stojan Djudjev, Bulgarian, Živko Firfov, Macedonian, Zmaga Kumer in Slovenia, or Claudie Marcel du Bois, French, etc.

And now we are very sure that for the entire Albanian intellectual world and those who have shown interest in culture and Albanological sciences, the name Ramadan Sokoli has become synonymous with scientific achievements in the field of Albanian music studies. Up until the 1990s of the last century, like everything else in Albania, both Ramadan Sokoli’s work and his personality itself were overshadowed by various restrictions.

Now, after 16-17 years, since I wrote a series of articles on Ramadan Sokoli’s scientific activity in the magazine “Fjala,” and those same articles were subsequently published in several installments in the newspaper “Rilindja,” which was published in Tirana at the time, I feel a sense of pride that I initiated the actualization of his personality and activity. Interest in him exploded, they began inviting him to cultural events, writing about him, but what is more important, his professional and scientific activity intensified enormously. Many articles and books followed, many themes and problems of our culture were addressed, not only musical but Albanological in general.

It is very correct of Albanian ethnomusicology colleagues that they do not hesitate to note, on any occasion, the fact that Albanian ethnomusicology begins with Ramadan Sokoli. Following are some sincere thoughts expressed by current ethnomusicologists, his successors.

About him, Vasil Tole, composer and ethnomusicologist, writes: “Until the first publications of Prof. Sokoli around the 1950s, Albanian ethnomusicology did not exist. Among his entire creative opus, the works on musical folklore, and specifically on ethnomusicology, hold the foremost place, works which are, among others, the foundational works of Albanian ethnomusicology in general. In a certain sense, the entire ethnomusicological contribution of Prof. Sokoli is like an encyclopedia of the transfer and explanation of the phenomenon of Albanian musical folklore, across a very wide time and space. This is stated by researchers, musicians, students, and pupils of music, for whom he oriented and introduced the subject into the school structure, as early as the 1950s of the last century.”

The well-known Albanian researcher and composer, Sokol Shupo, expresses himself similarly: “Meanwhile, Ramadan Sokoli’s activity extends across the entire spectrum of folkloric research. He participates in special and joint folkloristic expeditions with foreigners (the Albanian-German expedition in 1957 and the Albanian-Romanian expedition in 1958), publishes a very large quantity of folkloric materials and studies (hundreds of articles and 16 books – now the number of books is greater – R.M.), and becomes intensely involved in Albanian cultural life, especially after 1982.”

His work has had significant echo around the world and has been assessed very positively…! Ramadan Sokoli’s contribution to the development of Albanian ethnomusicology is very great… because his numerous publications visibly influenced the growth of the sensibility and the training of ethnomusicologists educated only in Albania. The reference is to the publications, (R. M.), which were a kind of “Bible” for this profession. Thirdly, because for Albanian creators, the systematic knowledge of Albanian folkloric material creates real premises for expressing themselves with a rich language, in an Albanian element.

We add here that it is not only the fact of being the first to start ethnomusicology or the folkloric material or the educational contribution that makes this personality distinguished. These are just aids to open a path to his rich career in the field of music studies.

His research and studies in the field of music extended wide and deep into the entire complexity that music encompasses in human life. Ramadan Sokoli made the song, the dance, and the musical instrument the object of study, with the entire spectrum that these three activities of the spiritual and material culture of man include, across time and space.

He did not do all this superficially or just for the sake of doing it, but he did very serious, enduring, and resilient work, for any time and any modern “trend” of scientific studies. From the beginning of the 1950s of the last century, an interest awoke (which did not cease for a moment until the end of his life) in knowing the Albanian ethnomusical wealth as closely and as well as possible. He also started early to make the material he secured the object of study. In his scholarly opus, no genre, type, or manner of singing has remained unresearched and unstudied with great professionalism. He dedicated serious study to lullabies, to këngët e buta (lyrical love songs sung by men), epic songs, humorous songs, laments, këngët përmajekrahu (mountain songs), patriotic songs, ritual songs, and many, many others.

He is the first Albanian researcher and scholar who, with scientific competence, undertook the study of Albanian polyphony, where, besides the spatial definitions of this manner of singing, he demonstrably delves into its genesis, its types, and the melopoetic analysis of this extraordinary and unique Albanian singing.

The Albanian world, as well as the foreign world, became familiar with the wealth of Albanian folk musical instruments through the studies of Ramadan Sokoli. Following the methodology and consulting renowned global organologists such as Kurt Sachs, André Schaeffner, Hornbostel, and others, Ramadan Sokoli succeeded in raising Albanian organology to the level of European studies. He grouped them according to professional organological criteria, delved into their origin, the duration of their practice, their spread across Albanian territories, ergology, and the socio-cultural role and function of each instrument individually and in formations.

He created a small museum while he was a professor of folklore at the “Jordan Misja” Artistic Lyceum in Tirana. He wrote the first book on folk musical instruments, and a revised edition was published jointly with the organologist Pirro Miso, a book that was also released in Italian last year.

The scholar places the subject of vocal music or singing within the system of analysis. Sokoli approaches this issue from the methodologies of other European ethnomusicologists, and particularly in models by Béla Bartók, Constantin Brailoiu, Zoltán Kodály, Stojan Djudjev, etc., naturally offering terminology that corresponds to the Albanian language and viewing them as more functional and adapted. Thus, for some morphological components of folk songs, Ramadan Sokoli created his own unique names that contextualize the element in question.

When the scholar of Ramadan Sokoli’s work observes his breadth across the different values of Albanian musical folklore wealth, they must inevitably rank him among the successful scholars of ethnomusicology, ethno-organology, and ethno-choreology. Ramadan Sokoli easily identifies phenomena, ways of singing, folk dances, and musical instruments, defines their spread across Albanian territories with scientific arguments, raises the issue of belonging, and observes their connection with the cultural life of the environment where they were practiced in the past and are practiced today.

On the analytical level, he is the first and unsurpassed scholar who lays the foundations for the theoretical definitions of the morphological components for song, dance, or instrumental melody, which determine the characteristics of the entire Albanian musical system. Memorie.al

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)