By Ahmet Bushati

Part fifty-five

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

For no more than three months, in the magnificent camp of Berat

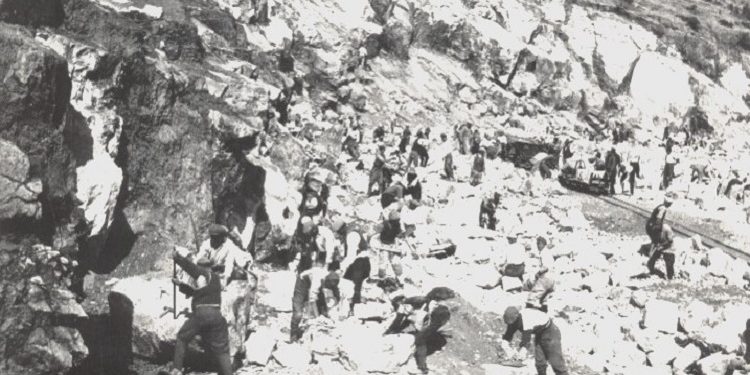

Let’s not dwell on the usual events of a labor camp, from the 1952 camp, we left Çengelaj and headed for the camp of Ura Vajgurore, “Laperdha” of Berat, where other prisoners had long been working on the construction of a military airfield. In this “magnificent” camp, we joined two camps and would stay together until the one of Vlashuk, which was our destination, was ready. The Ura Vajgurore camp would be remembered as the largest camp that had ever existed, albeit for a short period, with more than four thousand prisoners, as well as the camp where a majority of political prisoners would get to know each other and from where they would one day leave, having left and received indelible impressions for a lifetime.

Among others, there we would also meet our friends from Shkodra, who had left the camp after us, such as Sami Repishti, Xhevat Meta, Ernest Perdoda, Tomë Sheldina, Et’hem Bakalli, Zef Nika, Nush Tuka, as well as Feti Quku and Mark Lleshi, who were going to prison for the second time, etc. We would also find in that camp friends from other prisons with whom we had known and connected two or three years earlier in other camps. The meetings of the political prisoners, after some time without meeting each other, would be like meetings of comrades-in-arms. Such meetings would constantly create a joyful and encouraging atmosphere, for the very sufferings and the common cause they had.

In this camp, for the first time, we would meet Father Meshkalë, in whom, like perhaps no other, simplicity and sincerity, intelligence and culture, as well as a warmth to the point of affinity with us, were merged into one thing, which would make him, despite his age and the clothes he wore, manifest them to us from the very first meeting with us. Father Meshkalla would be impressed by his appearance, which, although somewhat dark and wrinkled, would make us attractive and endearing, also due to the immediate approach and the unreserved trust he was showing for us.

The experience on the one hand, as well as the contact with people chosen in terms of character, who had a relationship with him and sometimes also in terms of culture, added to these books and especially the goals, had made a category of prisoners of a young age, have acquired that level of premature formation, so much so that they would have been a real benefit to the country, if communism had been overthrown, since then.

Even there in Berat, as in other camps, we would meet many good people, among whom were also simple villagers, whose names, due to the long time that had passed, have been erased from my memory, but not always the faces of some of their nobility. As long as we were in that camp, we would hardly wait for the working day to end, to meet in the evening individuals and groups of friends, who, with their unyielding stance in prisons and camps, had made a name for themselves.

From the prison of Vlona, Meçan Hoxha would be one of those pure nationalists and a good man, whom perhaps more than anything else, the calm and kind expression of his calm face, the low and reserved tone of the measured and confidential words he used, would indicate, as a man with whom we had known for a long time, which would make us, as young people as we were, believe that all of the above, stemmed from his pure and deep nationalism, like rarely anyone else.

A very good man from the prison of Vlona would also be Fatos Kokoshi, who was able to show you an endless number of films, which he had once watched in France. Likewise, Abdurraman Kreshpani, another devout nationalist, who years earlier had interrupted his studies in Italy and returned to Albania to fight the Italian invaders with weapons in hand, enlisted within the ranks of the National Front. Engineer Besim Grezhica, another good and unyielding man. Likewise, the Vlora natives, somewhat younger, like Ventigjar Hamzaraj, who had completed several years of high school in Paris, as the son of an Albanian embassy employee who had been. And so did the young men, Numan Numani, Teufik Gabrani, Lavdosh Begja, good and determined boys, who remained, as before, loyal to the National Front.

In that camp I became friends with a Bexhet Shehu, despite the difference in age that I had with him. He had studied in Austria and by nature was a model of a kind and loving man. Once Bexheti would tell me: “I can’t say that I believe in fortune-telling, but it is true that my sister-in-law saw my arrest in the cup, two days ago. She looked at the cup of coffee that I had just drunk, and immediately her face melted and her eyes filled with tears. “What did you see in the cup”? I asked her, and she did not answer me for a moment, but after I insisted, she tremblingly said: Bexheti, I will see you in prison. And indeed, in those two days I was arrested”.

As a friend who already had Bexheti, one day I would ask her the question: “Bexheti, among the prisoners, who is sacrificing more, you who have left wives and children at home, or we who are wasting unrepeatable years of youth here”? “Dear Ahmet,” – Bexheti would begin to speak to me with a smile, – “this question, which is truly interesting, is difficult to give a correct answer to. You have to find someone else”!

Shyqyri Borshi would be as charming to the prisoners of that camp as he had once been to the girls of the Shkodra square. His cheerful temperament and constant humor had made him known and loved by everyone. Sometimes Shyqi, riding on a wagon filled with earth, passing in front of the prisoners who were at work, would call out to them as loudly as he could: “Hey, hey, the artist of the prisons and camps of Albania is passing in front of you”.

Shyqi’s family, originally from Borsh in the south, had been brought from Podgorica to Shkodra ten years earlier by the war. They had arrested him for nothing, when he had been a soldier somewhere in the south. He didn’t even want to know about politics and he would have told me once: “When I went to Zagreb after the war to continue my university studies, I left Shkodra to deal with politics. At home and on the street, I would hear people saying: these people are leaving today and are leaving tomorrow, and now the English and Americans are coming, etc., etc., while when I was studying in Zagreb, I had the impression that no one there thought of dealing with politics, and that we students were only concerned with our studies and love. I returned to Albania, and I found Shkodra again dealing with politics, just as I had left it before”!

Another charming boy in that camp was Qamil Kacmoli from Shijak, a guy with a loyal, cheerful, expansive and loving character, and a strong body. They said that during the war, he was one of the bravest men that the Shijak area had. They had imprisoned him for the disappointment he had suffered. Mark Prela and Sami Repishti, who had been friends with him from before, had introduced him to us and connected us with him. I cannot forget on this occasion, two simple villagers who worked closely with us in those days. I think they were from Vloçishti in Korça and, because one of them, had the name Izet, whom we called; “Uncle Izet”, as he was old. We removed General Nexhip Vinçan from his position since then, he had his own.

Uncle Izet and his friend, since the end of the First World War, had emigrated to America and their stories about America, however simple they were, still attracted and satisfied our curiosity. Another villager from their side, named Koço, was constantly with them, who like the two above, had also worked for several years in America and, among other things, would tell us: “On the 4th of July, the American Independence Day, groups from all over the world would parade with flags. Albania, according to the alphabet, came first after America and for this, the Greeks almost burst with rage and for every anniversary they would protest, saying that the Albanians should not pass in front of them”!

Towards the end of our stay in this camp, the command would discover the opening of a tunnel, in the front face of a large earthen septic tank. And it was going to be very bad. There was a time when a group of prisoners, in secrecy and great danger, had worked for many nights to open that tunnel and, as on other occasions, only when he wanted only a little more work to get out of the barbed wire fence, they would discover them and sentence them to many more years of prison. Another insignificant episode would happen to me on one of those last days of our stay in that camp: while I was a little away from the place of work, I saw that inside a bush, something was stirring.

I quickly grabbed a shovel and started to pave the way towards it, and soon noticed that there was a nursery of young snakes there, which I started to attack with the shovel, while they were coming towards me calling my name, Met Rrapushi, – the well-known baker in Shkodra – and the former student, Merxhan Smajli, who, shocked as they were, were begging me to stop that work. The way they were asking me for that thing – as if they were asking a stranger, not me, their friend – as well as the sparkles of tears in their red eyes, added to the words “Aman Ahmet, you don’t know what a snake has inside you”, made me not only immediately withdraw from that action we had just begun, but from the pain I was feeling for them, I didn’t even know how to apologize for what I had done.

Vlashuk Camp

It was still winter when one day, in camp no. 2, getting into the cars, we left the camp of Ura Vajgurore and, many of our old and new friends, and, winding for several dozen kilometers along unpaved roads, along the sides of low hills, we arrived at a place that did not seem like a village or anything, which was called Vlashuk. It would be a camp – the year 1953 – from which the work front would never leave, since the works would be concentrated on opening a canal of short length, but of great dimensions, both in width and depth.

There would come a time when, to extract the excavated soil from the bottom of that 25-meter-deep canal, they would need thirteen alternating piers, on both sides of it, through which, shovel after shovel, the soil would come out. In the depths of the canal, the light penetrated little and the soil there had a color between blue and green, because it was very compact and it also smelled of a heavy smell, perhaps similar to that of pyrite or stone dust, and which often made one want to run their noses.

The work at the end of the canal, apart from the difficulty of digging through a soil as hard and compacted as glue, as well as the eventual dangers it posed, had two advantages during the summer season: the coolness and the water collected in small ponds along the canal, water with which we could quench our thirst and that of many other friends, above the piers, without wondering about its unpleasant taste, which it had acquired from the stench of the soil from which it came.

In order to prevent the deep sides of the open canal from collapsing, an incalculable amount of wooden material was consumed for their lining, but nevertheless, due to the great pressure of the masses of earth on the sides, and especially after any rain that might have fallen, saturated with moisture as they would be, they would sometimes lose their points of support and cause the two sides of the canal to come together, ruining our work of several days. To our luck, the collapses would occur continuously after midnight, so much so that we prisoners, laughing, would say: “It seems that God has begun to love us.” When spring came with its extended days, the work would be organized into four six-hour shifts, which would change at the beginning of each week. Fate would have it that five of the six people who had our table would be on one shift, while I alone would be on the other shift.

During the week that I would have the shift of work after lunch, the role of cook for lunch would be performed by me. It was at that time that I continued to study the English language, by means of an Italian “Lisly” method, and in order to practice it, any order I had for my friends, when they returned from the first shift, whether it was related to the dish or something else, I would let them write it in English, on a piece of rough cement sack paper.

Inside a camp of about two thousand six hundred prisoners, – most of them political – sometimes you would not fail to notice the faces of the prisoners and you would see them for the first time. The political prisoner usually maintains connections within a fairly wide circle of friends and acquaintances, as well as preserving and respecting some acquaintances that he may have come close to by chance, which usually more or less close the world of his prison people, outside of which he generally does not go. So, one day, after finishing work early, from the depths of the canal where I was working, I climbed up to wait for everyone to finish their work. The occasion led me to enter into conversation with a prisoner from Berat named Qemal, who was working there with a large electric crane.

From the beginning, I was impressed by that man’s clean, very white face, as well as the calm tone of his voice, which whenever he spoke, he would accompany it with the smile of a good and polite man. After a conversation of about an hour, we parted as if we had known each other for a long time. After the second shift had finished, that is, in the evening, when we were having dinner, I would talk about him to my friends at the table. But what happened? By an incredible and fatal coincidence, these friends of mine would tell me that exactly that crane operator, named Qemal, had been run over by that crane after lunch, spilling his guts and brains out!

The death of a prisoner in a labor camp sometimes passes with indifference from those who had never known him before and with the deepest sorrow from his comrades. Thus, a friend of Qemal’s, who I think was named Nuri, from the sorrow for Qemal’s death, from that night on, played with his mind. He was isolated inside a small barracks, which was a little behind our shed, and for a week that boy, day or night, would not stop calling out in a loud voice: “Qemal, oh Qemal, Qemal, oh Qemal!” – filling him with pain and even leaving many prisoners there without sleep. Ruzhdi Baja, my cousin, who at that time was sleeping next to me, worried that he was not falling asleep from the calls of that Nuri, would mutter: “That boy hurt us enough, we don’t even let him close his eyes, we are tired like that, I don’t know what to say”! However, a week later, we didn’t hear Nuri calling anymore: someone told us that they had taken him to the hospital.

In this Vlashuk camp, I remember with respect and now only by image some good people from Berat and its surroundings, among them especially a short man named Syrja. As a Syrja, I also remember from Berat on this occasion a former student, a little brown and charming, who had one parent of Italian origin. The student Ilia Thereska, who had attended high school in Gjinokastra, was also from Berat. Likewise, camp after camp, we would get to know and become very close to a group of very good colonists, who had at their head an old man named Muço, Muço Shkëmbi, a gentleman of great prestige, who deserved the honor that was given to him by all.

The youngest among them would be Kamberi, whom we would call Kambo. Already in the Berat camp, we had met and created social ties with intellectuals, such as Isuf Vrioni, who as the son of the ambassador who had been in France, had completed all his school cycles, including some years of primary school, in Paris, where he had been awarded twice and, a third time in Milan, Italy. We would also get close to his two friends, Milto Lito and Foto Bala, who, together with Isuf, would form an inseparable trio.

Foto Bala grew up with Enver Hoxha. They had attended the Gjinokastra semi-gymnasium together, the Korça high school together, and Montpellier, France together. Foto Bala was not only a complete intellectual, but he also had a very charming and eloquent way of speaking. Among other things, he would tell us about Enver Hoxha, about his behavior in general, about his complete lack of character, about the feminine “manners” that he used to the point of disgust, whenever he had to do with women, as well as about his many adventures, many, many times dirty.

“It would be Enver Hoxha, the only Albanian who would pose shamelessly for hours and hours in a Paris bar, waiting for some old, rich client who, in exchange for a payment, would take that beauty with her,” Foto Bala would tell us. He continued: “As depraved as he was, who knows how many times he would crawl into my bed, a few hours after midnight, saying to me: “Foto, Foto, make a little room so I can get in too”. And when Enver came to power in Albania, the witness to his many antics, Foto Bala, he would keep him in prison for ten years, and his father, who had been a pharmacist in Durrës, would be shot, to which Foto would say: “That bastard, he’s fine with me, but what about my father”?

We would get to know many more good people and become friends in this camp, but I will at least remember two more, one Niko Koka and the other Lem Daçi, both from Shkodër, arrested in Durrës, where they had recently been working and living, as well as a certain Eshref Zagorçani from Pogradec, who had interrupted his higher studies in Austria a few years earlier. Among others, we would have had there also the student Ali Cali, from Tirana.

Continuing to be in this camp, it happened that one Saturday at dinner, the family brought food to one of the friends at the table. Uncle, – our steward and cook – was busy with arranging them. Thabit Rusi, not being able to see well in the poor light of the bunker, accidentally knocked over a bottle of vodka and, behind him, began to cry; “Where has it been that I didn’t see it?! “Damn it”, etc. Meanwhile, Maliq Bushati, since it was not time for sleep, was lying on the mattress and covered with a blanket. While Thabit continued to vent his anger over the loss of a bottle of wine so precious to us, I would notice how Maliq Bushati was shaking and shaking under the blanket and after I discovered him I asked: “What are you shaking about?”?! and he could not hold back his gas and, continuing to shake even more, would answer me:

“Thank you for pouring another duel, because you are left talking about everything; “Maliqi, Maliqi”. And truly, if something was spilled or broken, if something was torn or stolen, they would generally have Maliqi’s hand, arm, leg, knee or head as the perpetrator. Likewise, if even a louse was noticed to have entered our places, we would be sure that Maliqi had brought it, even if he had worn dirty clothes that day. He did it this way, because Maliqi Bushati, like no other, would take them into the recesses of the poorest and most forgotten of the camp.

Every morning, Uncle would fill the tobacco boxes for everyone, especially Maliqi’s, and he would even fill them with his hands, and when he handed them to him, he would say: “Maliqi, this is enough for the whole day, huh?” And Maliqi, although he would immediately answer with “Yes, yes”, when he returned from work, like none of the others, the first thing he would try to do would be to extend the empty tobacco box to Uncle, because as always, he would have met Preka, Hajdar, Nduena, Muho, and even Koço or someone else, with whom he would constantly share his tobacco.

Whenever Maliq Bushati received something new from home, such as a shirt, pants, etc., he would think that they did not belong to him and would generally throw them at me, as the youngest at the table that I was, which of course I would never accept, just as I would not accept a morsel of meat that might have fallen from the pot, and which he, taking from himself, as soon as he started eating, would ask me to throw in my basket! Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue