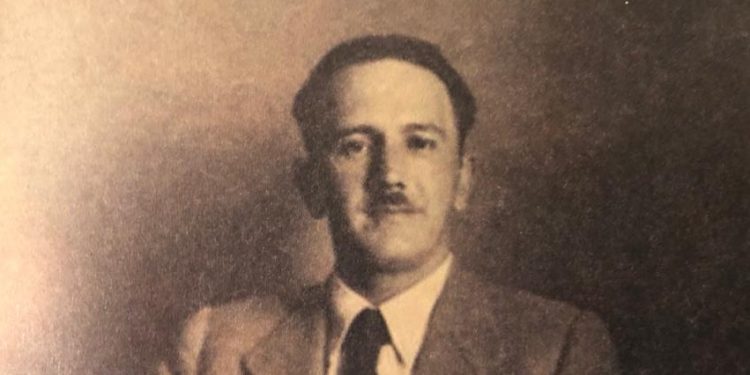

Ejëll Çoba

Part seven

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the memoir of the author Ejëll Çoba, the well-known intellectual from the city of Shkodra, the sucker of one of the most famous families of that city, who after graduating from the University ‘La Sapienza’ of Rome in In 1932, he returned to his homeland where he practiced his profession, pursuing an administrative career, as ‘Dottore in Giurisprudenca’ and then for several years in the senior state administration, where he also occupied the period of occupation of the country, (1939- 1944), where he held several senior positions, as Director in the Ministry of Justice, Secretary General of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, etc. His arrest in 1946, (together with his brother, Kelin) accused of participating in the ‘Postriba Movement’ and after a long investigation in Shkodra and Tirana, was sentenced to 25 years in prison, of which he suffered a full 23 years and five months, and five days in prison, in the terrible camps of forced labor, all the way to Burrell Hell. The unfamiliar memories of Ejell Çoba, which come with a foreword by his fellow citizen, the well-known writer, Zija Çela, present to the reader a panorama ‘painted with the brush of pain’, which provides details and details about his sufferings in the camps of the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, as well as other accomplices, known and unknown names, such as: Father Bernardin Palaj, Guljelm Suma, Syrri Anamali, Ramdan Sokoli, Cin Serreqi, Father Karol Serreqi, Father Filip Mazrreku, Hamdi Isufi, Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela, Musa Gjylbegu, Asim Abdurahmani, Prof. Selman Riza, Petrit Merlika, Kolec Deda, Nikoll Deda, Felatun Vila, Gjush Deda, Sali Vuçiterni, Emin Bakalli, Qani Katroshi, Sali Doda, etc., as well as some names of investigators, guards, State Security officers, such as Fadil Kapisyzi , etc.

Continued from the previous issue

Imprisonments

Memoirs written from August 1973 to the end of December 1977

Only extreme things can be tolerated

Count Rober de Montesquieu

When the director wanted to go out with him, there was a lieutenant whom I knew, but Hamdi, who extended his head over his shoulders, said and extended his hand:

- Give me your hand, Comrade Lieutenant Gaqo! The lieutenant leaving said:

- I will not shake your hand! – Forgive me the power and you do not give me a hand?!

I do not know what stopped me from saying to Hamdi, “What do you need his hand for?” Lieutenant Gaqon, Hamdiu had a subordinate, in the Gendarmerie or in the Police. After the others left, the captain told us:

- Gather your clothes, go upstairs.

Then we hugged the three cell mates. The captain said a little in tone, “Wait a minute,” and locked the door. Hoping that the captain would not be late to come, we tied our clothes and lay down with our friends.

A guard, who was doing the usual check, when he saw from the counter that we had collected the clothes, opened the door and told us:

- What are you waiting for, why not?!

- We are waiting for the captain to go up to the prison – we told him.

- Who knows when the captain comes, and for tonight he will not let you go out.

We slept that night for a full eight more days. Capt. How nice it was to hug our friends, and he hoped that for our families, out of joy they would bring special food or powdered coffee, which was rare at the time. Pranaj left us there and a week.

The heat had started and there was a lack of water. Every day we waited to be joined by other prisoners. After 4-5 days, Hamdi told me:

- Are they mocking us?

- Even if they are ridiculous, they are doing us good, because we are sleeping peacefully.

But Hamdi was vindictive in nature and made plans for the future. He once told me that he would have to form a “black hand” to eliminate his opponents. I did not approve. On the other hand, I felt sorry for disappointing his dreams. He did not understand that the situation in Albania had changed, and he did not return. The political and social system established by the Ottoman Turks had forever disappeared as a feudal system in Europe. Albania was going through the birth of the bourgeoisie, even under socialism. There is a law in the development of social life, which no people can save. The Albanian people were going through a very painful period with many victims.

- When the captain comes to join us with the prisoners, let us not leave our clothes, but let them take care of us so that they do not leave us here.

I laughed at Hamdi’s grief. One day when a guard brought us food, he told us:

- Were you scared when you were told you would be sentenced to death?

- Why did it seem small to you?! The guard nodded in affirmation.

On June 24, 1947, while we were eating lunch and resting, the captain came and told us to get our clothes and go upstairs. We got dressed quickly and greeted our friends. In the hallway the captain gave us a pound of sugar that our families had brought us.

- What about coffee? – Hamdi told the captain.

- “They did not bring you coffee,” he said in a low voice.

One of the guards said to us, “Take that handkerchief, it’s yours!” In his eyes I took him and threw him in the yard outside.

When we reached the top of the stairs, we lowered our clothes into the hallway. The prison was quietly at lunch break. Suddenly, as if with a movement of the spring, the prisoners of the southern wing came out like bees from a hive! Everyone came to hug us with tears in their eyes. They had found out that we were executed and not Gjush Deda and Asim Avdurrahmani.

Engineer Petrit Merlika, gave me coffee in his cell. Then Ndoc Sheldia, arranged for me that it was the day of the name of the boy, Gjovalin. That day I felt an unforgettable pleasure from the hugs of friends and colleagues. Thus began my uninterrupted prison life, which would last 23 years.

Although I was forbidden to go to the other side of the prison, I acted like I did and went to meet Shuk Gurakuqi. A few days later, Pjetër Haxhiu told me that when he found out that Hamdi and I would be released, he was extremely excited. We trusted him because he nurtured sympathy for us. A special moment of joy was the meeting I had with my sister and brother after 8 months, although with two pairs of acres.

I also became interested in the other brother, Kelin, who was an unpunished prisoner. I was afraid that my salvation from death would weigh on him. I did not trust the justice of that time, nor the judges and their decisions. We were not informed of the charges against him. Of course I did not tell him about the torture they had suffered. Also, I did not inform them about what I had removed.

In general, the mental state of the prisoners was optimistic and even euphoric. Most believed that the revolutionary impulse was coming to an end, and that a quarrel would break out between the communists. So it could have somewhat mitigating consequences for prisoners. Even the few who were not optimistic supported this, so as not to fall into pessimism. I saw this path as inappropriate. Only Shuk Gurakuqi did not believe that the situation would change and did not believe that there would be internal or external signs that would collapse the system. But he also believed in their optimism. I soon began to remember that some young opportunists had begun to realize that some communist ideas were appropriate, and that their frontal opposition had not been appropriate.

In the Albanian nationalist world, we definitely saw many contradictions, but while these were non-antagonistic, if we used a Marxist expression, we had to study the way to solve the problems in the future. But what surprised me was the conversation I had one day in the prison yard, with professor, Selman Riza. Selmani was Kosovar and studied at the Lyceum of Korça with very good results, and then graduated from university in France. I was surprised by an article he had published in Branko Merxhani’s magazine “Përpjekja Shqiptare” where, although Kosovar, he defended the thesis that the official language should be Tuscan, to explain that the official language should be Tuscan, t ‘ He explained that the language of Elbasan, adopted by the Literary Commission of 1916, in fact did not exist, after Aleksandër Xhuvani himself, wrote the most beautiful Shkodra. Despite the linguistic merits of such an thesis, I appreciated his intellectual independence and the liberation of his soul from any provincial conditioning.

One day, in prison, Selmani asked us to talk in the yard at the time the prisoners came out to get some air.

I definitely accepted with pleasure, because I too had longed to resume the old conversations with him. When we met, Selmani spoke without interruption, for almost half an hour, and explained to me what conclusions he had reached in his political thoughts. I was so surprised by his words that I asked him.

Am I talking to Selman I know, or someone else?

Yes – he replied – I fully approve of the ideology and actions of the Albanian communists, but I do not declare it, just because it will be interpreted as opportunism and bigotry.

Unfortunately, I had no other opportunity to argue with Selman, because after a few days, he was handed over to Yugoslavia to be tried for his actions in favor of Ethnic Albania. I do not know if he was convicted there and with what activity he was dealt with.

A translation room was set up in the prison, where Mit’hat Aranitasi, Kostandin Boshnjaku, Mihal Sherko, Selman Riza (who had Viktor Dostin as secretary), Filip Fishta, Suad Asllani, Kadri Hoxha and others were created. In the same room was also Shuk Gurakuqi, who did not deal with translations, but collected for himself the Albanian terminology of plants.

One morning, the radio and the news that Llesh (Sander) Gjonmarkaj had been killed with three friends, who had fled to the mountains of Mirdita. A few minutes later, as I was walking down the hall, I heard a voice shouting, “I was strangled, I was strangled!”

I saw Esad Malon, running towards the “bars”, the prison gate. After a while, word spread that in the student room after the news of the murder of Llesh Gjonmarkaj, everyone had comforted Deda, Zefi’s brother, his cousin, and then everyone had gone to their place, to remain silent. mortal.

The command immediately closed the student room. 3-4 officers came from the ministry, who took the students out of the room one by one and beat them with kicks and fists, threw them all in the cells on the ground floor, and left them in the cement for a month with bread and water.

Those were the years when the Albanian press found in the Soviet Union the most advanced science, the most perfect morals, the most realistic literature, the most artistic cinematography, the saving sociology of humanity, the fairest regime, therefore the most refined tortures there, would be found from there they took the Albanian executioners. Many times in my sleep I heard the cries of the victims who had not been able to drown out the deafening accordion, and those sad scenes appeared to me rather than in a nightmare. And those who suffered were Albanians of our provinces, of our faiths, of all walks of life, especially peasants, poor people, few beys, many intellectuals, most with true nationalist feelings, with different views, among them both socialists and social democrats, even disappointed national liberators and communists.

Newspapers began to provide correspondence from the trial of Abdyl Kokoshi, engineer Klosi, etc. Abdyl Kokoshi denied all the statements made by the investigator, telling them that he had been tortured. He had charged himself and many others with them, including my brother Kelin, who allegedly agreed with the Catholic clergy through Abdyl’s organization. My brother was paying for me. This infuriated me beyond words. The next day, when the presiding judge resumed the hearing, interrogating the other defendants, Abdyl asked for the floor and stated: “What I said to the investigator is all true.” The presiding judge did not seek to explain why he had denied them the day before. Understood: Abdyl wanted to inform the public that the statements of the investigator, as well as the statement of the second day in court, were the effect of coercion. Whoever wanted to understand me, understood him.

Kudret Kokoshi, Abdyl’s cousin, later told me that when they learned that Abdyl had denied the investigative allegations, he, like their uncle Qazim Kokoshi, who were in prison in Vlona, were so happy that on the same day, at lunch, Qazim was overjoyed and died. Sadly, such phenomena have occurred at all times and in all places. The stories of oppressive regimes are full of false claims and self-inflicted wounds.

In 1947, most of the prisoners still did not believe that the previous situation could be restored. They expect an immediate change in the political situation, but from whom and why ?! No one knew they gave me a credible answer. The biggest surprise was that even the families in the meetings, nurtured such a euphoric hope.

Every day new convicts came, telling us about new convictions, about torture and especially about facts and events, about masses and propaganda, about the submission of dissidents who were believed to be faithful and safe witnesses of the opponents who fled from Albania, and about none effect of the activity of fugitives abroad. But in prison, very few were those who saw how much our cause was lost, both inside and outside. It is surprising how some of those who had learned that the head of the English delegation, when they presented him with a memorandum, still said to Gjergj Kokoshi, still had hope, continued: “For twenty years, I will you have these ”. When I tried to analyze this collective illusion, the following seemed explicable to me:

- The general belief in the ignorant and religious mass, that “what has been, will be”. I do not know where this fatalistic illusion comes from, without foundation it will have nourished the soul and heart of all those Albanians who, during the Turkish rule, remained loyal to Skanderbeg’s ideal. For them, too, for more than four centuries, no objective sign of salvation has existed, but the illusion that “what has been, will be” has comforted and strengthened them. With this illusion hope they fought and died bravely.

- Among the intellectuals we did not have in-depth scholars of history, nor did we have people to practice interpreting facts and events, let alone a realistic generalization of the situation. We did not understand deeply and convincingly, that the Albanian people were a chess piece in the hands of two blocs and, as such, could have no weight even for themselves, could be worth to themselves, just for that as much as one or the other block allowed.

When the Bloc that would have supported the nationalists lost the issue in Albania, it was in vain, it was even harmful any continuation of the war by the Albanians. Albania was left to the Eastern Bloc, and any incitement by the Anglo-Americans was made solely for their plans in the Cold War with the Soviet Union, and no one tried to change the situation in Albania.

At the time, the hope for a Third World War was simply an illusion of drowning people. Those who had won the war against Hitler were delighted. There could no longer be a suitable reward for a third war. The mutual fear of the two blocs, as time has shown, was not enough to justify a third world carnage. So, Shqipnija was surrounded on a base, that no internal movement could overthrow or change the situation.

But ‘spes ultima da’ even for the imprisoned Albanian intellectuals!

Contrary to any cold reasoning, there was almost joy in the Tirana prison. I am saying “in Tirana prison”, that from the news that came to us in Shkodra prison, the blackest terror reigned, not only in the Section and the Investigator, but also after the sentence, in prison.

More than the calamity that befell us, it was to mourn the inability to consciously realize our miserable condition. Even among the few intellectuals who could grasp the essence of the Albanian problem, there was a silence, not to talk about it, and not to spread it, so most of the less prepared ones were disappointed in their hopes, and for consequently he fell into despair, or worse, sought other not at all honest ways for the Albanian character. /Memorie.al