Memorie.al / The “Cassandras” of the former State Security always existed as such, serving as raised spears to set traps and tarnish anyone who was not part of their “coven” and did not obey their owners. An insubordinate of the State Security’s “Cassandras” was undoubtedly Hilmi Seiti, an undisputed authority in the city of Shkodra and its surroundings due to his positive deeds. He became a victim of the very Security he believed he was serving in his own best, most humane way. Whenever this man’s name is mentioned in Shkodra, he is called “Baca Hilmia,” a term of respect for his work, not as a Security official, but as a human being above all else. The occasional emergence of some voices, which speak without documented facts and recount after 25 years of democracy what no one, knew and no one believed, compels us to revisit the character of Hilmi Seiti. Just as some lone person now tells “Cassandra” stories, as if they lived alongside State Security people who came after him, like Feçor Shehu, (after Hilmi Seiti’s death) and fanned them during their evening strolls, presenting them to us as typical Security “Cassandras” of ill omen. The question arises: Where were they during these 25 years, who are the victims and what are they doing, and where are their children, or does the imagination of a single person fill the world from a distance in time and space?

In any case, a full 64 years ago, a State Security trick physically eliminated a man known for his deeds in the heart of anti-communism, in Shkodra. I say physically, because the legend of Hilmi Seiti, the extraordinary Çam, lives on in Shkodra even today. A State Security official who, instead of being an enemy, was a friend to many opponents of the regime.

I heard about Hilmi Seiti about 25 years ago from Lutfi Sejko, originally from Filati, a former political prisoner, as part of the so-called “Hostile group of Teme Sejko and Tahir Demi.” “In Shkodra, they respected and knew him as Bacë Hilmia,” the Filati native Sejko told me, who had been an eyewitness to many of the events he recounted about Hilmi Seiti. But not only Lutfi Sejko, but also every Shkodran I met by chance who found out I was from Çamëria, immediately mentioned Hilmi Seiti’s name, speaking of his fatherly behavior in superlatives, using the epithet; “Baca Hilmia,” which is often said of dignified men and people who did no harm but always had opportunities to help anyone, not to put them in jail but to give them a chance to build a family life.

I have often heard good words from Shkodrans about Hilmi, even though so many years have passed since his mysterious death. Sixty-four years have passed since that day in April when, after returning from Tirana and after a conversation with the First Secretary of the Party Committee of the district in Shkodra, he passed away. The news spread, and the funeral of this man from Çamëria was big and special.

Today we can rightly say that what happened to Hilmi Seiti was the prologue to a new genocide that the State Security and the leadership of that time would implement against the Çams and every personality of this region, who, without a doubt, had contributions to the Anti-Fascist War and were boys from the best families of Çamëria.

After I wrote an article about this character from Çamëria with respected contributions to the anti-fascist war many years ago, there was a reaction from another writer that created indignation for what he said and tried to fill the minds of the readers. An elderly lady from Shkodra called me and told me that; “For me, Hilmi remains a great man. He treated us like sisters even though we were persecuted by the regime. I have kept in my memory the way he behaved with us, and I never heard anyone say a bad word about Hilmi. He was a man from Çamëria!”

Throughout Albania, a typical Security rumor mill began, which it fanned with its own people in every city with its own typical Stalinist Cassandras, even using the words that only the Greeks used against the Çams, calling them “faithless,” since even within Enver’s Bureau were his closest Greeks. But, as Hektor Sejko, the son of Taho who lived in Shkodra, states with the truth and seriousness that characterizes him; “in anti-communist Shkodra, this word was never said because Hilmi Seiti had created the portrait of a Çam of his word, a quality that is preserved to this day.”

It is not simply a memory of years, but a re-memory for that opinion that has often accompanied the Çam community, where besides the imprisonments and murders and many other wicked things that the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha used, the reminiscences of the past cannot fade the strength of the origin and vitality of a land that can truly be said to be as persecuted as it is dignified, as massacred as it is proud.

So many things have been said about Hilmi Seiti that a political prisoner from Shkodra, the blind singer-songwriter, Gjok Vata, quotes him with great respect in his book. Furthermore, Hilmi Seiti’s own son, who unfortunately did not know his father because he was a baby, remembers his father in this way, as a noble answer to the common gossips:

“I saw my father for years only in photographs: handsome, simple, with smart and authoritative eyes. As a child, I saw him in my dreams. I heard about my father from strangers who hugged me. I looked for him, they told me. I asked my mother. She told me how much humor he had, how loving he was. Everyone (around me) told stories. The years passed, but people did not stop, they kept telling stories…,” says his son Agimi.

“What’s your name? How are you related to Hilmi Seiti? He was a man! All of Shkodra loved him…! He found out that so-and-so wanted to escape…! He called him… he told him to go and start a job…!” Dozens of stories of simple people, he continues to hear even today. I do not believe there are many people who, not having known their father alive, have known him so well in his relations with others and in his work. A very delicate job. Facing people, superiors, himself. Rose as an orphan, far from home, among those young Çams helped by the elders of Çamëria to go to school. In dorms, in War, in internment, in a struggle with life, alone and at the same time with many friends, but who at no point accepted hypocrisy.

His son Agimi says that after the ’90s, it was periodically written in various newspapers, and the truth about his father’s death began to crystallize and match his mother’s early suspicion. “We learned that Hilmi Seiti was heavily criticized for softening the class struggle. We learned that, officially, Hilmi Seiti; ‘found no trace of the hostile activity of the clergy in Shkodra,’ although this had been requested from the beginning of the ’50s,” he says.

“We re-heard what we knew, that despite the specific profession he had chosen, unlike many senior leaders of the State Security and Police, Hilmi Seiti had known how to distinguish between misery and ideas. My father, Major General Hilmi Seiti, had chosen his path and as a man of integrity and rare intelligence, he tried to do his best, in that heap of almost medieval mischiefs and cruelties of the time. But he could not do crazy things.

The only crazy thing my father did was that he did not sell Çamëria, that he could not accept the anti-Albanian thesis that; the Çams, this so smart, vital and patriotic people, were in the service of Greece. His elimination was undoubtedly the work of the leading dome of the communist state and paved the way not only for the realization of the ‘Çam plot,’ but also for the cleansing of the intellectual and educated Çam generation, which had been formed with such care and difficulty by the elders and the so hardworking families of Çamëria. This was the next and dirtiest blow that the patriotic Çam population received, but this time it came from where it was not expected and, moreover, labeled them as faithless,” says Agimi.

Agim Seiti accidentally came across the book “My Diary of Memories,” written by Gjokë Vata. A friend of his, a Shkodran, Anton Daka, the son of a respected family that was deprived of a life of freedom during the dictatorship, like his father, Nikolla Daka, met him and told him about this book, inside which the author speaks with great respect about Major General Hilmi Seiti.

“I was surprised and read it immediately, even more so when I found out that the author was blind. The problems I have with my own eyes make me believe and respect this category of people who lack the most precious thing in life,” says Agimi, who has selected a few paragraphs from this book, where it talks about the Çam-general Hilmi Seiti.

Excerpts from the book by Gjok Vata from Shkodra

“It’s a wonder,” said Mark, “even the authorities of this shitty state try to trap each other. Mantho Bala knows you very well, but the support Hilmi Seiti gives you angers him. No matter how small the hope for a career struggle is, they try to exploit it. They fight each other with invisible elbows and imperceptible underhandedness. If Hilmi Seiti slips a little, they try to get him in trouble, even with the support they have given you. No one can ask anymore how Hilmi Seiti is slipping. When even higher-ranking officials slipped, why not him?!

I told Hilmi Seiti about the behavior of the authorities towards you, and he replied: ‘The persecution of Gjoka is not in the honor of the class struggle.’ These words of the most powerful man in Shkodra would open the doors of all institutions wide for you, and with what you saw in it, it would give you a hand to quickly climb back to where you slipped from!”

Filip Gjergji has given way to Hilmi Seiti’s words, and they have spread faster than they would have with a radio broadcast. General Hilmi’s reasonings are accepted without question by all the authorities of the city, so Hilmi’s attitude towards me has become everyone’s attitude or is pushed.

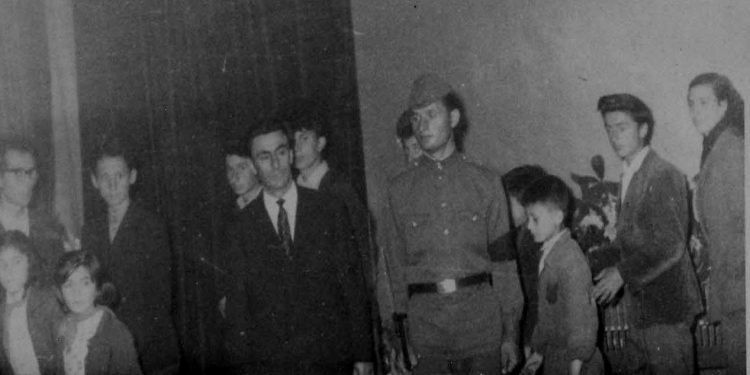

Some songs and dances during the performance were warmly applauded by the audience. The first compliment on stage was given to me by Hilmi Seiti. At the moment of shaking hands, the applause from the audience exploded even more powerfully. This applause had two goals: to express the warmest congratulations to me and the desire for my rehabilitation.

Hilmi Seiti’s example, whether they wanted to or not, was followed by all the authorities present. My musical performance was awarded the festival’s first prize. “This prize,” said Hilmi Seiti, “must fulfill the commitments I have made with your name. This commitment will give heart to my efforts to open the way for your rise, even if the progress is slow, the goal will be achieved as we wish.”

“Mark Tatiqi told me: In the public, people have started to speak ill of you. Hilmi Seiti’s hand-shaking is interpreted as an ugly concession that opens the way for spy favors. The gossip of the evil-mouthed turns my joy into suffering, and because of this gossip, my own doubt has started to linger, whether Hilmi Seiti’s support is related to some political conditionality?”

Prenk Jakova told me: “Hold on tight to Hilmi Seiti’s hands, the gossips will amuse themselves with their rumors. Hilmi Seiti has had it up to here with this number of recruits, let alone including you in them. You do not have the conditions to serve in that kind of recruitment.”

With the punctuality of every meeting, I arrived just before the scheduled time to see Hilmi Seiti. He took me by the hand and we went to his office together. “You have found me in a wave of work surprises,” he began, “so I have to speak short and clear. You are making some unforgivable mistakes; however, if I didn’t forgive you, I wouldn’t have called you here.

Nevertheless, know this well, I am one and the state is many. You and everyone know well, I am not that one miracle of the state; I am the privileged one to fulfill the duties they assign me.

I cannot become a defense lawyer for someone who attacks himself. I have called you to order you to stop the attacks against yourself. Not you and your friends, but even if I and my colleagues went crazy, we could not do anything to this state. Our state is the socialist camp, and the socialist camp is our state.

You have submerged yourself under the surface of the water, and if you don’t take your hand out to its surface, I have no way to grab your hand and pull you to the shore. You northerners have a saying; ‘excess has a miracle.’ As a northerner, do you respect this saying? Your only chance of salvation is to fight your enemies disguised as friends, and in this fight, you have me on your side.”

At 10 in the morning, I left for Fushë-Arrëz. As soon as we arrived in Pukë, the driver stopped the car and invited me to have a coffee with him. As we entered the café, a customer asked the other in a slow voice:

“How is this death of Hilmi Seiti explained, so sudden”?!

I trembled all over.

“Hilmi Seiti?” I asked the driver, as if my curiosity couldn’t wait to ask anyone else. Communism deceived him, I thought, and he put his flesh and soul in the service of that deception. His behavior with me and some others was a sign of repentance. Maybe that sign was the cause of his death. His kindness to me gives me a reason to pray for him. And if prayers are unacceptable, prayers are not punished.”

Epilogue

Shkodra had not seen a more magnificent funeral than the one on the day of Hilmi Seiti’s burial ceremony, because he was unique in his personality, and those who were eyewitnesses have told me that the Catholic gentlemen and ladies of Shkodra were in the front row of that procession for a man who only did good, and I have not heard anyone else tell me otherwise.

It is easy to make people laugh, but it is not easy to make them cry. He was mourned because he was a respected man whose origin from Çamëria made him proud and humane./Memorie.al