“Memorie.al / Inescapably, there comes a time in a person’s life when memories take on even greater dimensions. They appear to him, more clearly every time. They become even more beloved, and from the distance of time, not only do they turn into nostalgia, but they also serve to judge his past actions and those of others, or past events, with coolness and without passions. Generally, the desire arises to evoke them more and more often, during conversations with friends, over coffee tables, to the point that perhaps without realizing it, he bores his interlocutors. However, those who are patient and have a certain inclination prefer to organize these memories and put them down on paper. Thus, by publishing them in a book, he might even hope for compliments and say to his friends and companions that; ‘you have become a writer now in your old age’?!

He is left with nothing else but to laugh bitterly and tell himself; ‘whether good or bad, I did my job. After all, the chatter will be swept away by the winds of oblivion, while what is written here remains! But there are also those who, after reading these memories, understand that thanks to their culture and talent, they are genuine writers and it saddens you that; despite the paths of life, they should have exercised this talent much earlier, with true literary creations.

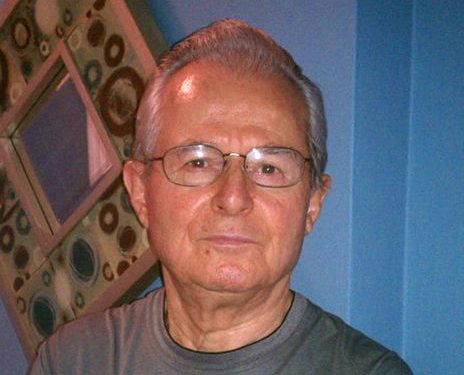

I found such a person in doctor Prenjo Imeri, the brother of my dear professor and friend, author of several worthy books, reserve colonel and forever young, Xhemal, after reading his voluminous book; ‘Nostalgia and Regret’. With this book, he fulfills that early promise before his mother’s grave that: ‘I swear mother / upon your grave / that for life, I will erect a monument for you’!

With a phenomenal memory, the book is a collection of wonderful stories that together form a true novel, just as the author himself called it. This is what James Joyce used to do with ‘Dubliners’, for which he informed the publisher that he had the aim of ‘…writing a chapter of the moral history of my country…! I have tried to present it to the indifferent public under four aspects: childhood, adolescence, maturity, and public life’!

But even if it is not exactly like that, it is good to remember what someone said about ‘Village Life’ (since we encounter such life here most often), by Amos Oz: ‘In this book, there is everything from life on earth, in this type of life, there are people and animals, with scenes and paintings among dogs, which, by chance or deliberately, enter into each other’s lives.

Written this way, every reader has the right to read this work as a novel. But ‘Village Life’ is not a novel, but pieces of linked life, which give and take among themselves like arteries of a body, such that they give it the life of an intriguing being. True to his psychological game, his portrayal of characters, and his detailed descriptions of life and nature, all wrapped in the historical background of the time in which he lives’!

I mentioned earlier the talent and culture of the author, but how worthless would they be if this type of literature, i.e., biographical storytelling, lacked sincerity? For the time when the author lived his childhood, was educated, and worked, was filled in itself with lies and hypocrisy, therefore today it should be told just as it was; without masks and gloves, without fear of hurting someone’s feelings, and without angering anyone.”

“Perhaps sincerity is the most irreplaceable assistant of the art of writing. The tragedy of the years when Prenjo Imeri was born was like that of all other villages in Albania, with its good and bad sides. However, for their love for the homeland, the tragic people were the first. His father, Seferi, just as his name suggests from Turkish, was a fighter of the first hour, a just man, and a strong character.

A nationalist, loyal to his anti-communist ideal, he was treacherously killed, together with the brave Hysni Lepenica, there in Grehot on September 14, 1943. The elder brother, Bilbili, separates from the National Liberation Movement and finally leaves the country, ending up in America. Meanwhile, the other brother, Xhemali, joins the partisans. After the liberation, the members of this family, which had already given significant contributions to the struggle for freedom, found themselves unsure of where to stand…?!

In fact, they were like most Albanian families, where communism, with its strict and diabolical rules, badly divided them, and according to circumstances, tried to keep them subjugated according to the principle: liberate and tighten. With will and perseverance, they were educated both domestically and abroad. But the letters and secret reports, the surveillance of Security agents, never departed from them, until Prenjo was brought back from the German Democratic Republic, while his brother, Xhemali, after Enver Hoxha’s deliriums about ‘hostile groups’ in the Army, was expelled from the Party and Army.

Even though some looked upon them with disdain, they, convinced of their honesty, regardless of their plight, never separated from the village. With what love and longing Prenjo describes the old tragedy that had left such an impression on the English painter Edward Lear, that he almost called out;

‘Go, O painters, visit the mountains of Vetëtima,’ those good and generous people, their customs inherited from generation to generation, the places where he roamed as a child, climbing from tree to tree, the sheepfolds where he tended livestock, the school where he learned to read and write, the springs of Izvor at the top of the village, where he quenched his thirst in summer, the meadows filled with the scent of flowers, those itinerant traders called pramatarë, that broken minaret mosque, the delicious figs of Shëngjin, and even the legendary barn of Mother Sulltan.

With considerable competence, the author clarifies the endless toponyms of that area and details the main historical events of the village. And then men and women, regardless of their importance in life, are seen as parts of a whole, presented with truthfulness and the smallest details. There are joyous and bitter events, yet they remain in the memory. The efforts to enroll in school, the studies, the friendships, the joy among them, attending school ‘Skënderbej’, he paints with warm watercolors, for they are joyful years that are remembered for a lifetime.

And then working in the Elbasan Corps as a military dentist, the friendship with the good Russian colonel, Zarçenko, and the transfer after being released from the Army. He keeps the best memories of the leaders and workers of the Krrabës mine, who valued him as he truly was.”

“Furthermore, it provides details about traveling abroad, the struggle for better results, the necessity of maintaining dignity as Albanians, cultural activities, the lectures of the albanologist Maximilian Lambertz, his company with girls as an inseparable part of youth, and then the unexpected return to his homeland, where they had not forgotten the ‘suicide’ of his uncle (March 2, 1951, due to the incident with the bomb at the Soviet embassy), the brave and crazy warrior of the war, the high-ranking cadre and deputy Sali Ormëni (Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs and General Director of State Police), and the continuation of his studies here.

How much gratitude this man has for everyone who was there when he needed support the most. It is heartbreaking for those who are no longer alive. There are dozens and dozens of characters in this book. While evoking their lives, Prenjo often uses a subtle and clever humor. At the beginning of each chapter, he has chosen and placed a striking quote that is part of his erudition.

In the language he uses, dialectal terms and almost forgotten official words appear frequently, but they are part of the syntactical wealth and make the description even more credible. There is also a rather interesting solution when he leaves the life of Sefer Ismail Imeraj, his father, declared a ‘Martyr of Democracy’ by the President of the Republic, to the very interesting and striking notes of his brother, Bilbili, with whom he met in the USA after a full 53 years.

And since we are in this great place, a champion of democracy, I conclude these notes with the words of William S. Faulkner from New Albany, Mississippi, who in his speech upon receiving the ‘Nobel’ prize, said this valuable expression for any serious writer: “I am convinced that man will not merely endure; he will prevail.

He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an unquenchable voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of suffering, sacrificing, prevailing. The writer has nothing to do but write about these things. It is his privilege to assist humanity in surviving by giving them courage, by raising their courage, honor, hope, compassion, mercy, the sacrifice – the glory of his past!”

Thus, Prenjo Imeri has fulfilled this duty excellently with his monumental book “Nostalgia and Regret.” / Memorie.al

Copyright©“Memorie.al”

All rights to this material are exclusively and irrevocably owned by “Memorie.al”, in accordance with Law No. 35/2016 “On Author’s Rights and Related Rights”. It is strictly prohibited to copy, publish, distribute, or transfer this material without the authorization of “Memorie.al”; otherwise, any violator will be held liable under Article 179 of Law 35/2016.