By Eugene Merlika

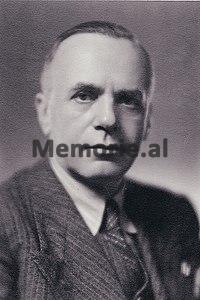

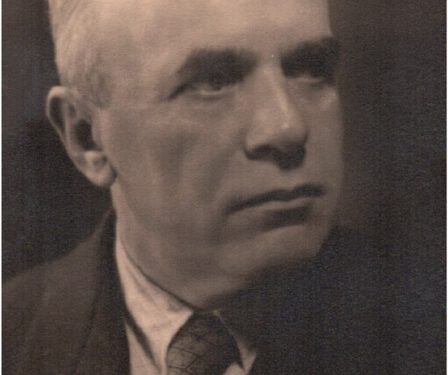

MUSTAFA KRUJA

(Formation, character, personality in society and in the family)

Memorie.al/ A full 50 years have passed since that evening of December 27, 1958, when Mustafa Merlika Kruja closed his eyes forever in an American clinic, near the famous Niagara Falls. A surgical intervention in the temple, seemingly simple, marked the end of the parable of a complicated life, which began on a stormy March night 71 years ago, in the legendary Kruja of Arbër, interspersed with most events turbulent times of the first united and independent state in the history of Albanians, ending in the sad loneliness of a long exile in different countries, until the welcoming shelter of the country symbol of democracy.

In the city where he was born, he only spent his childhood, but Kruja remained in Mustafa’s heart, not only as the place with which the first and indelible childhood memories were connected, accompanied by portraits of family members, among which the most prominent is that of the mother with the pain of deeply of her premature departure, but also because her name was attached to his surname to form that group of words, which would appear in the most important document of Albanian history, becoming a point of reference in political life, social and cultural of Albania.

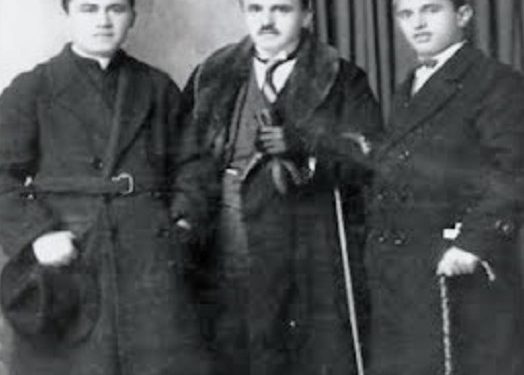

At a still tender age, at the dawn of boyhood, he took the paths of the world to study, first in Ioannina and then in the capital of the Turkish Empire, in a decisive period for the formation of national consciousness and the establishment of the Albanian State. The boy from Kruja successfully passed all the school tests, climbing the ladder of knowledge one by one, thanks to an iron will, above-average intelligence and an unusual determination to achieve his goals. These were some of the most prominent features of Mustafa Merlika’s strong personality. A great hypothetical law of compensations of potential possibilities and actual conditions, in his case, probably served as a powerful impetus to move forward.

Born in a middle-class Cretan family, without an office or wealth, aware that he would open the path of life only with his own strength, he stood out from a young age for his broad horizon of cultural interests in various fields of knowledge.

Naim Frashëri’s poems, “Albanian lyrics, we sing them, we feel them, we understand them and we appreciate them”, and Sami Frashëri’s treatise, “the greatest scholar that our race has produced so far”, were about Albania. connected to his country of birth, but the French learned early opened the horizons of the Enlightenment, introduced him to the paths of 17th century essayism (La Bruyère, La Rauchefoucauld), and even to the theories of socialism. The Turkish school he attended gave him the opportunity to penetrate the broad areas of Arab, Persian and Oriental culture in general.

With this cultural wealth in mind, at the age of 23, he graduated from Istanbul’s famous Mylkiye University for Political and Administrative Sciences. The patriotic activity, which started with the writings in the Turkish notebooks of the time, from that moment on was consolidated and took shape with the return to the Motherland and the refusal to accept the position of the vice-governor of a province of the Empire.

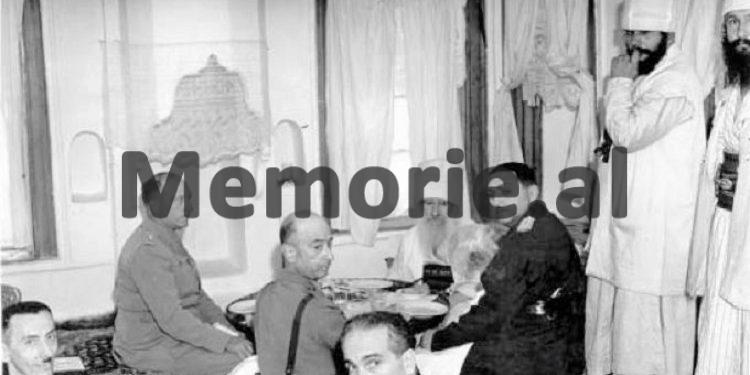

On the activity of Mustafa Kruja in the political field, linguistic and historical studies, and on his political opinion, prominent researchers spoke at the commemorative scientific conference, held in Tirana, on the day of the 50th anniversary of his departure from earthly life. I will try to present here the portrait of the man Mustafa Kruja, a portrait best sculpted by authorities of Albanian culture such as Ernest Koliqi, Karl Gurakuqi, Tahir Kolgjini, Lazër Shantoja, etc., who knew him closely and collaborated with him.

I am fortunate to carry on his blood, I am the grandson born in the year in which he finally left the Motherland. I was only five months old when my grandfather hurriedly left for Austria, where my little uncle, Besimi, was very ill in a clinic in Vienna. Before he left, on a day at the end of August 1944, he took me by the arm, kissed me, and with a hint of despair whispered: “I couldn’t raise mice by myself, I won’t be able to raise this either.” In the old album of the first year of life there is a picture of him with me in his arms. Thus, the “permanent exile”, as Koliq would define it, began the last cycle of his exile, the most painful and difficult one. He faced it with the strength of character and honesty, for which he had been distinguished since his youth.

If a list of Mustafa Kruja’s personal qualities were to be drawn up, I think that at the top of it would be honesty, in the broadest sense of the word. It was a quality born but also cultivated in a patriarchal family, where human values were instilled in the child from the moment he sucked his mother’s milk. We were a people poor in means of living, in experience of civilization and in culture, but rich in traditions, principles and human values such as faith, keeping one’s word, respect for the elderly, for family, for parents, for friends the benevolent

Mustafa Kruja was a son of this Albania, which, unfortunately, is in its last throes. Throughout his life, he worked to bring this Albania into the groove of European civilization and contemporary development, haughtily saw the humility complex, thanks to the preservation of those properties. Pride in the human virtues of his people accompanied him everywhere and whenever. Moments of its appearance can be found in his “Memories…”, from the episodes of the merchants of Vienna and Thessaloniki, to the “Inn” of Kruja, and the memories of Dom Nikoll Kaçorri.

Honesty, displayed in all moments of his personal, family and social life, was a source of pride for the entire Merlik tribe who loved his “Lala” to the point of worship. In the long years of exile, in the “hermitages” of Egypt, Italy, France or the USA, he told his sister Haxhire, or his son Bashkim, the only family members around, to call him “Lala”.

Thus, he said, it seems to me that I have my whole family and tribe…! It was a form of hypnotism itself, to ease the deep pain in his soul. His honesty was admired by his friends and associates but also appreciated by his opponents. Honesty was the perfect correctness in dealing with others, but it was also respect for the convictions that he openly displayed in the complicated game of politics. His correctness in the context of married life has remained proverbial.

In “Memories of childhood and youth”, an episode of a conversation of the author with Luigj Gurakuqin and Father Gjergj Fishta, in a restaurant in Paris, is shown, on this very topic. Luigj Gurakuqi was single, he was a handsome, generous man, coveted by women. In his personal life, especially in Italy, he did not lack the latter. Although Luigji was an idol for Mustafa, he did not spare his criticism in that direction, his friend, “married to Albania”, reminded him of the “mistake” he had made, creating a family in a country where often the consequences of the actions of politicians, fell on their family members. But for Mustafa, the family was the most necessary and respected institution in human life, a task that should not be avoided under any circumstances.

Thus, to the remark of his son, Petrit, on the inadequacy of the act of marriage in the period of war, he responded with a long letter, in which he defended the thesis that wars have never been in the history of mankind, obstacles for people’s marriages and child births. This is how his perseverance reached the goal of marrying his son to the daughter of his old friend, Sotir Gjikës, Elena. This was the only daughter-in-law he had at home, a daughter-in-law who in a short time became a real daughter for him, not by chance she was the only one in the family who called him “Daddy”, finding in him the missing love of his father who left him an orphan at the age of 7.

And she loved and respected him with all the strength of her soul and, during the ordeal of more than forty years of communist persecution; she bravely faced the long suffering because she was Mustafa Kruja’s girlfriend. The parent’s heart was very happy when he found out that the second son, Fatosi, had married the niece of a friend and colleague, Kola Biba Mirakaj. He did not manage to take with him the joy of the marriage of his third son, Bashkimi, but he always answered the letters of the future bride with the warmth of a parent.

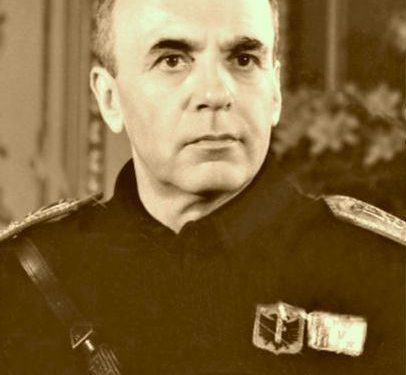

At the age of 25, in Vlora, he was the secretary of Ismail Qemali, for whom he always maintained his respect and conviction that: “The old man of Vlora”, was an unblemished patriot who worked for Albania. Loyal to this belief, he opposed Esat Paşe Toptan, the man who had decided the direction of his education, which he almost paid with his head. Delivered to Esati as a result of his threat to kill all the males in the family, he did not hesitate to tell him the reason for his attitude.

Faced with the danger of death, it took courage and courage to reveal your beliefs and hostility to the powerful, with your hands tied. Courage and courage were integral parts of his character, which did not like the twists and turns of politics. He was more of a statesman than a diplomat; he worked more driven by principles and convictions than by personal interests. Major for him were only the interests of Albania, as he conceived them.

Everything could be sacrificed before them: profit, position and even family. To protect those interests, he does not hesitate to challenge public opinion, risk “compromise” and put his career and well-being at stake. He did it in 1915 in front of Esat Pasha; in 1922 when he organized the March uprising with Zija Dibra; in 1927, when he left KONARE, because he did not see the Soviet spirit prevailing in him; in 1936, when he addressed his fellow exiles with a letter, in which he proposed a change of attitude towards the Albanian Kingdom, after the Government of Mehdi Frashër came into power; in 1938, when the representatives of the Italian government were in talks, he addressed them with the words: “Let Zogu stay another hundred years in the government of Albania…”; in November 1941, when he took charge of the government under occupation, with the sole purpose of avoiding a victory of communism in his homeland; on December 28, 1942, when he met the demonstrators in Vlora with the flag in his hand; in January 1943, when he resigned as Prime Minister, as a sign of breaking cooperation with the Italians; in 1952 when he approached the US State Department for political asylum, arguing the reasons for the pro-Axis position in World War II.

As determined as he was to defend his political, scientific or moral convictions, he was equally willing to discuss them openly, honestly. The late Mark Temali told me in the Gradishta camp, how a two-hour conversation with the former prime minister had turned him from an opponent of the Government into a collaborator, accepting the federal job in Korça.

After the speech in the “Savoja” cinema, entitled “In the depths of history”, he was ready to welcome anyone who wanted to talk face to face with him about the country’s problems and ways to solve them. He had no prejudices of any kind; therefore he was ready to listen to the views of others, of any age, of any time, of any province, of any political persuasion, as long as they served the Albanian cause.

He was a man who liked order in everyday life and seriousness at work. He was extremely devoted to every kind of activity he undertook, such as intellectual, scientific or political, as well as family matters, relatives or social and friendly circles. He was a staunch opponent of anarchy, disorder, casual work, lack of seriousness. In his concepts of public life, a special place was occupied by the element of discipline, without which he could not understand the smooth running of the State and its institutions. Discipline was not a blind submission to the superior authority, but a sense of respect for the duty that everyone had a sense of responsibility towards the implementation of the rules and laws approved by the institutions.

Another property of Mustafa Kruja’s character was the lack of shyness to recognize mistakes even in the space of time. In “Memories..”, he does not attribute the burning of the house in Krujë, after the failure of the March 1922 Movement, to the “barbarism” of the State, but to his own fault. In fact, he called that movement, together with the Revolution of June 1924, after the passage of years, harmful actions for the democratic progress of Albanian political life. In this framework, the changes in attitude towards his strict opponent, Ahmet Zogut, can also be placed.

The entirety of their relationship, from the acquaintance at a very young age in a school in Istanbul, to the fraternal neighborhood in Alexander of Egypt, contains in itself everything that highlighted Albanian politics in the first half of the last century. It was an expression of ideals but also of interests, of respect towards the opponent but also of merciless war against him, of his private appreciation but also of public denigration, of persistent standing in convictions but also of changing political affiliations.

In the autumn of 1943, when it was seen that the victory of the Axis, with all the benefits of ethnic Albania, was getting further and further away, while that of the Allies, with the risk of the communists prevailing in the structures of the anti-fascist resistance, became more tangible, Mustafa Kruja came to the conclusion that Albania had only one way out: the mobilization of all the strong forces of the Nation, under the direction of the exiled King. From the house of Captain Gjon in Shkodër, the message for the opponent of many years is sent: “Like me, like the Captain of Mirdita, you will have us as collaborators and supporters”!

It was the outstretched hand of the King and the conscious recognition of his role and abilities, not for political convenience or personal gain, but for a deep conviction that this was the way to avoid a catastrophe, which he had forewarned in every way. . Before this goal, all evaluations, attitudes, grudges of the past were put aside, surrendered to the time of history. It was undoubtedly an indicator of masculinity and Albanianism, just as it had been, a year before, the defense of the thesis that Albania united with Kosovo in semi-freedom was more acceptable than that without Kosovo in freedom.

In short, this was the figure of Mustafa Kruja, on whom the mud of slander and discredit has been systematically thrown. It is connected to an era, now distant, to a mindset, a way of conceiving the Albanian issue, in one of the most complicated periods of a century marked by tragedies of all levels. Just like that mindset, in its entirety, that figure also awaits an objective and impartial reassessment today, through the sieve of true history.

Unfortunately, the scientific, political and cultural structures of our country are not yet able to do it, they remain trapped in the ideological towers of communist thought. The commemorative conference in the “Balsha” hall of the Tirana Hotel was a powerful step in that direction. The papers given in that hall, by eminent scholars who expressed their opinions are a testimony. To them goes the heartfelt thanks not only of the family and relatives of Mustafa Kruja, but also of that social opinion that is eager to know, in its true terms, the past of its country.

The rewriting of history, the main word of this gathering, must be a deep, continuous, transparent, qualitative, continuous process, a process of reconstruction based on the criteria of the truth of our past, this phenomenon is necessary to overcome the fog of huge deception that, for more than half a century, has darkened the minds of Albanians by perverting their ideas. Memorie.al

December 2008