By Eugjen Merlika

THE MISSION OF THE WRITER

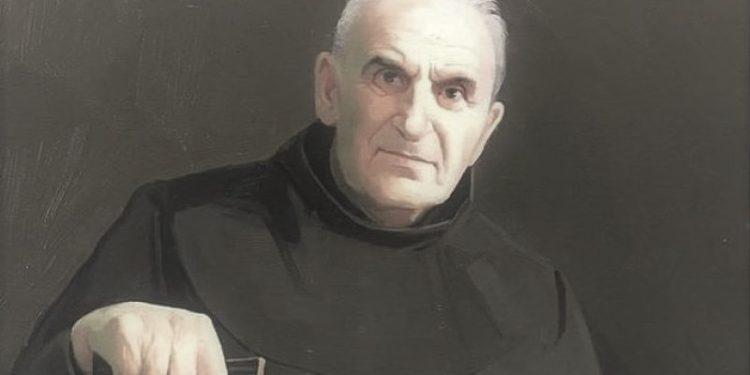

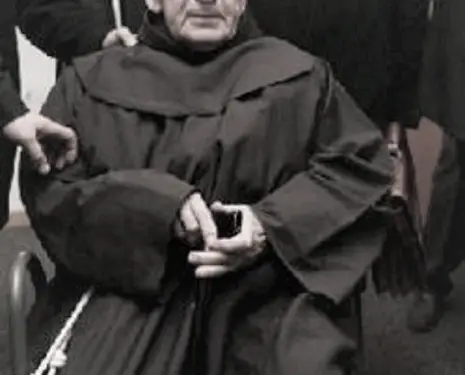

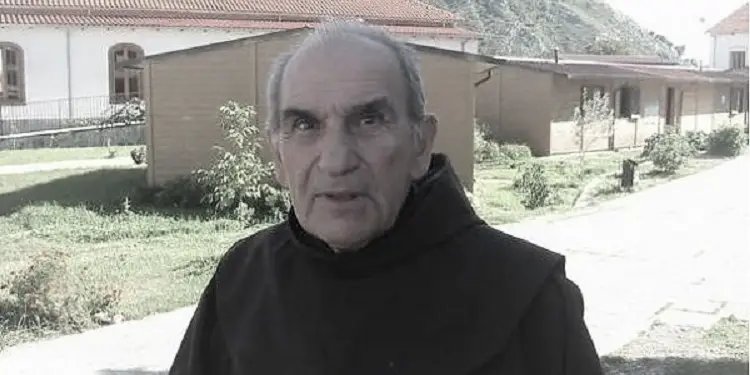

(Reading the book “Rrno për me tregue” by Father Zef Pllumbi)

Memorie.al/ “God is great. We thank them for the river that created death; otherwise people would always have slaves of tyrants. They too will die one day, and you will have to live only as long as you tell me. Never, if you are not good enough to do that, stay just to show me. Do you understand what I have to say? The others are finished, we are finished, so are you: everyone goes like a dog to the grapes, but there is no one to tell me how the work is done. Whoever exaggerates let him report! ”

These prophetic words of the old priest, Father Marin Sirdani, addressed to the author, then still a young boy and, not consecrated as a priest, constitute the light-motive of the work of Father Zef Pllumbi. It was a valuable message, one of those bequests “that does not dissolve the earth”, which sets in motion all the energies, devotion, spiritual, moral and possible motivation of a man of letters, which aims to serve entirely a sacred purpose , the unfolding of the truth. In the consciousness of the author, that trust becomes faith, ideal, dream, meaning of life; accompanies him every hour, every day, every month, for decades, on a long, difficult road, always uphill, which is the life of the writer.

That trust gives him strength, will, endurance, to challenge the sphinx, to survive in a jungle where savages rule, where every day he is in danger of being mutilated, lost, and annihilated. That trust turns into a powerful light that illuminates every cell of unusual memory, to lay on paper all the life baggage of a personal and general experience, which constitutes the backbone of the work that materializes and takes the form of a book of memories, entered, I think, with dignity in the fund of Albanian letters.

“November 28, 1944, was a cold, gloomy day, perhaps gloomier since the declaration of independence”, is a sentence at the beginning of the work, it is the first brush that warns its color. Gloom covers the entire pages of the book, reflecting the atmosphere in which an entire nation entered, after a tragedy that spared no one on the old continent. But in the place of the author, the tragedy would have macabre proportions, before which even the Shakespearean world, would seem dim. The author is a missionary and his mission is multifaceted. As a writer he must present with art the troubled era to which he belongs, as a parish priest, a member of the Catholic Clergy community, he must defend his reasons, as a politically persecuted of the regime he must, witness the drama of that part of the population that the “new time” put a yoke on his neck. As such, but also as a person, as a citizen, he ranks on the side of the possible, of the victims, of those who suffer history, but with the full awareness that he must reflect the truth, only the truth. This is one of the main merits of the memories of Father Zef Pllumbi, to remain faithful to the events in their reflection, as they happened, with lights and shadows.

This fact is very important, if we consider that it is a reflection of an era in which the truth has been violated fourfold, in all its manifestations, for half a century, serving you backwards an entire people. Liberation Day was anthem zed in all its forms became a dominant motif everywhere, in the arts, literature, historical and social sciences. It was always presented in symbiosis with the victory of Europe against dictatorships; it was called by the majority as the culmination point in our history of the last century. In fact, that day brought to the throne a regime that relied on deception and violence and which, unfortunately, thanks to its longevity, was able to insert its tentacles into the tissues of various segments of society, creating false taboos in the mindsets and consciousness of a part of the two generations of Albanians.

As for Father Zefi, “The terrorized Albania had fallen into a coma. The knowledgeable people knew nothing at all and the ignorant people had everything in their hands; what was not known. Through various episodes the deeds of the partisans are described, in which he participates in the first person. The objectivity in the evaluation and presentation of persons and events is obvious: for conversations we can mention the conversations with Shefqet Peçi or Mehmet Shehu, the episode of the prison guards Dhimitër and Tomorr, the trial against the Catholic Clergy, the talks on the Statute of the Church, etc. The author has set himself the task of witnessing all his experience. He remains in the center and around him revolve events and persons who, for better or worse, relate to him. The writer’s gaze is very wide, it captures a 360 ° angle, everything that radiates the material, spiritual, intellectual life of the environment in which he finds himself, the customs, the customs, the philosophy, the history, the politics, the culture of his people.

The author’s memoirs span a long span of time, resembling a Sage throughout the communist period, from birth to its collapse. Most of them belong to prisons and labor camps. This, not only for the fact that the author’s life, for force majeure, was spent more in them, but also for a certain philosophical subtext of a reality dominated by a dictatorship, which found its ideal expression precisely in those camps and prisons. Through real characters, encountered in these environments, characters that directly or indirectly, have made the history of their time, through the stories of their lives outlines a place which has been turned into a great prison. In it, everyone sees the birth of the day with suspicion, because he does not know what will happen to him until the evening, the border between “ours” and “enemies”, has almost disappeared after, as soon as he closes his eyes, the former fighters, the leaders of the Party, the generals, the writers, end up in cells, from where they continue to believe the tale of communism.

The description of those prisons, in all their creepy authenticity, is the greatest help that the author of the ep of Albanians and their history. Those fragments of eternal life embedded in the work prove how far organized crime in the form of the State has reached, and will be valid for the future, when Albania has become a normal country and when History will be written in its terms truth. Those evidences will shed light on a reality for which, unfortunately, in Albania and more in Europe, there is a tendency to reduce it, to forget it, to erase it from memory. The author is aware of this, given that this possibility, contradicts the legacy he has received in his rite: to show. He does not stop, he continues to remember and tell, convinced that his story will not always fall on deaf ears.

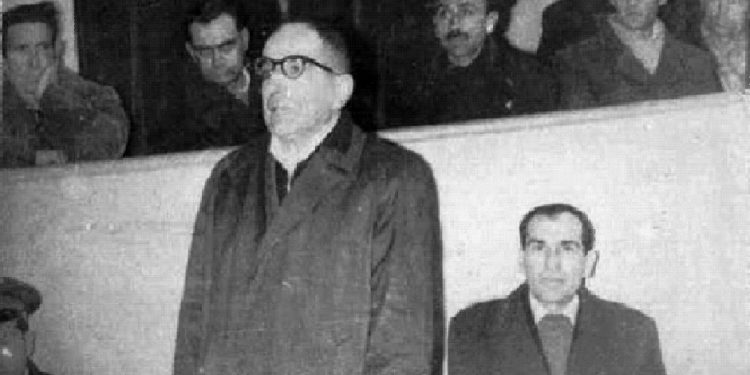

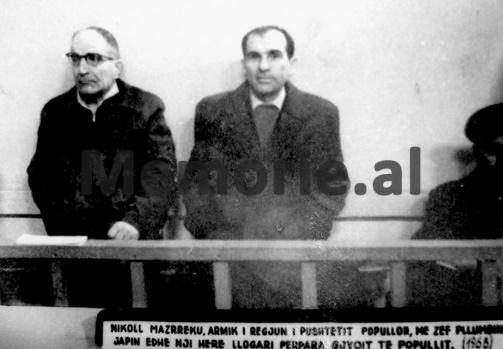

But the author has a purpose in mind that relates to his mission as a servant of Christ. He wants to present in the light of the truth his Church, this institution that was one of the most militant, on which fell the “lightning of Zeus”, in a special, inseparable way, with the greatest severity, to the point of paradoxes. Why was Albanian communism so bloody with religion in general, and with Catholicism in particular? Because, as I said above, it was a system based on deception and violence, a phenomenon that any religion, especially the Christian one, calls unacceptable and fights by all means. In order for the building to be erected, the foundation had to be cleared of morality, immorality had to be put in place, anyone who opposed the latter had to be annihilated. The Albanian Catholic Church refused to side with the regime, refused to legislate crime, refused to sever its centuries-old ties with the Vatican. Here, then, is the reason for the unparalleled barbarism that was martyred more than any of her sisters, that was threatened with complete extinction like no other.

What did the Catholic Church represent for Albania and the Albanian people? Undoubtedly it has been one of the most qualitative parts of the superstructure of this Country. Traditionally, one of the most powerful temples of our culture, gave a fundamental contribution to the formation of the national consciousness of Albanians, had extraordinary merits in cultivating in the people love for the Homeland, its language and history, played a decisive role during the Ottoman occupation, in preserving national identity, gave Albania an invaluable treasure in various fields of culture. Its most prominent representatives, in the centenary we left behind, such as: Dom Nikoll Kaçorri, Father Gjergj Fishta, Dom Ndre Mjeda, Monsignor Luigj Bumçi, Father Anton Harapi, etc., were the leaders of Albanianism of ‘Baballarë Kombi’.

These truths, denied for a long time by the regime and its tools at all levels, the author masterfully reveals through the portrayal of figures, philosophical interventions, political conversations, historical memory, episodes that treat the archive or library. In the eyes of the reader parade, in the light of truth, superiors or colleagues, martyrs of religion and nation, each with his own personality. They easily enter his mind and remain long. The author’s ability to portray the characters seems to me to be really outstanding. It seems appropriate to me to bring here an excerpt from the great trial in the editorial office of ‘The Star of Light’. Father Mati Prendushi speaks that, compared to his judges; he looks to me like Gulliver with the Lilliputians:

“For several centuries now, those who did not want either religion or nation, but we have always called the Albanian Catholic country, of Gjergj Kastriot, have been stuck among us and hanged on a rope. We have always lived with the people both in war and in peace: in war with the Turks and with the Shkyas, because one kept us in captivity and the other wanted to devour us. While we have never been given by the people, but we have tried to teach and give them the culture that Europe has and not to be badly distinguished from others. We have opened Albanian schools and we have not distinguished either Catholics or Muslims, enough for the Albanian people to walk in the way of God …”!

Lapidary words, engraved in the marble of the nation’s conscience, affirming a denied, tarnished truth, turned upside down by a gang of institutionalized criminals at the head of the State, for the misfortune of Albania. Father Zef Pllumbi restores this truth in the minds of the readers, fully achieving his goal. The figures of Father Anton Harapi, Father Gjon Shllaku, Dom Alfons Tracki, Father Pal Dodaj, Father Ciril Cami, Father Mati Prendushi, Father Donat Kurti and many other priests remain in the memory of the reader, in the simplicity and at the same time in their splendor as ministers of the church of Christ, as people, as Albanians.

The portrayal is also effective in drawing other figures, of those who in this half-century-old saga of memories, are part of the victims or the victors. It is quite striking the portrayal of the tools of dictatorship, of those “silent heroes” or not, that other powerful pens of Albanian letters, for decades praised them, clothed them with glory and even represented crime, violence, immorality.

“Look Dul, these are very important documents for the history of Albania, so pay special attention to them!

“Do not be fooled by P. Marin, because this nonsense is not worth it to us at all: we write history for ourselves!”

It is said that Hitler gave a rough answer when someone had the courage to remember the crimes of his armies and history. Dul Rrjolli was a simple ignorant partisan, but the mentality that his words express is that of the arrogance of the most extremist part of the Albanian communists who managed to dominate and take power, with all the consequences that Albania suffered.

There is another powerful impetus to the writer’s mission and that is the love for his people and the country of his ancestors. It is a powerful feeling, mixed with pride and pain, but which in some cases erupts into an anger that reminds us of Chernyshevsky’s expression about the Russians: “Nation of slaves, bottom and top all slaves!”

“What would the world have said when they saw that the whole life of this people, after Easter, was dissolved in the boat, without being able to ever get to its feet”? He exhales in a moment of despair, when he sees that the cult objects, the places where his people had been forgiven for long centuries, that had withstood the storms of the times, were now collapsing by unconscious crowds, infected by fear and ignorance. He sees this moment as the deepest abyss into which his compatriots are immersed. He knows full well that the resurrection will be extremely difficult and he must go through a great test of love. He tries to pass this test every day of his painful hell, in relations with his accomplices, especially with those who, until recently, were part of the crowd of his executioners. This is part of the writer’s mission, in addition to that of parish priest, because art in its genes has the preaching of love between people, generations, peoples, love that builds family, society, Nation. How far from their mission were those writers who, in all their work, glorified the “class war”, the “class hatred” between the members of a people, of a nation, between the speakers of a language, who evoked the empty weapons for congratulating communism ”and his“ heroic ”deeds!

From the height of his mission, aware of the heavy weight he has taken on his shoulders, with the modesty of the artist and the religious, the author addresses his contemporary reader, but also that of later times, with a request as simple as and complex:

“The events shown here are very difficult to write, so the author asks you to forgive him because he is not a writer, and kindly advises you qi, to reflect a lot on these events and look for the real reason why they happened …! Why”?

The author’s question goes beyond the dimensions of his work and strongly strikes the conscience of a society that carries within itself the unpunished crime that is the Albanian society. But it goes even further, crossing the fragile boundaries of the plot and heading for the big world, where a whole so-called “progressive” culture remains indifferent to them, always emphasizing only one other type of crime, that nazifashist. The theory of two weights and two measures, which conditioned for almost half a century every step of the life of Albanians, in democratic Europe continues to be prejudiced among the expectation and analysis of their history. It is no coincidence and the silence of the latter regarding the opposition between the Albanian State and the political persecuted of communism seeking compensation for years of unpaid work in forced labor camps.

The author’s mission is extremely noble and praiseworthy. It would be beneficial not only for the truth, but also for the spiritual renewal of the Albanians, to be embraced by a larger number of art servants. These kinds of writings would be very valuable, especially for young people, to have the opportunity to create an accurate picture of what a terrible absurdity their parents and grandmothers lived in, what was the responsibility, where their strength or weakness appeared.

The literary and artistic merits of the work seem to me to be abundant, the great generalizing ability, the fluent language and style, the gallery of the characters and the diverse environments, the accurate reflection of the truth of life. I tried to present the impressions on the main values of the message that comes from the book “Rrno just to show me”. Various aspects could be analyzed much more widely and, I believe, will be the subject of more qualitative criticism.

As a reader, I consider it appropriate to express my appreciation, gratitude and deep respect for the personality of the author, who I will unequivocally call an ‘Albanian Solzhenitsyn’. Memorie.al

June 2003