By Arnaldo Canciani

Part two

Memorie.al / This first part of my memoirs, which covers a period of twenty years; 1928 – 1949, I dedicate it to all those who have lived and suffered like me in Albania, the inhuman deprivations and sacrifices of my parents, and my entire family. I extend my dedication, to many Africans forced to emigrate in search of better living conditions, to all the soldiers who were forced to fight in a foreign country for transient ideals and, many of them, have not seen their families again and are buried in a foreign country, to all those who are oppressed by dictatorial regimes and those unjustly sentenced to death, to the prisoners, to those who have suffered unimaginable torture.

PREFACE

Continued from the previous issue

April 7, 1939: The Invasion of Albania

On the night of April 8-9, 1939, we woke up at three in the morning. We started gathering clothes and some things in a suitcase, then we got on trucks to reach the port of Vlora, 90 km away from Devoll; here the cruiser “Pola” was waiting for us in the harbor.

Embarked with all the refugees, the ship set sail and in just three hours, it disembarked us in Monopoli, Puglia. At a canteen, we were served breakfast and found that we were being treated with kindness. The soldiers of the “San Marco” battalion, who would disembark in Albania in the afternoon, were asking for information and news about the local situation.

The cruiser “Pola” was the twin of the Garibaldi, a recently built, modern battleship: 10,000 tons, with a crew of 1,500 sailors. It was sunk by the British in 1942, in the Battle of Cape Matapan. For Italy, this was a great loss.

The invasion of Albania by the Italian army ended in a few days; there were only rare sporadic cases of resistance, but soon, everything returned to normal, and so we, too, had to quickly end this short period of vacation. In Lecce, we were guests of our colleague Telini, from whose windows we could see the entire field filled with armaments.

After ten days, the people returned to Albania and resumed the interrupted work. Families were not allowed to return immediately: so my mother and sister went to Gemona, and spent a month in Italy. I spent a month in Devoll alone with my father. For people who did not have a family, there were canteens and single rooms next to them. Those who had their own family home had to settle in them.

But finally, the local situation, after the Italian invasion, was completely normalized and put an end to our disrupted comfort, and my mother returned from Italy. The days, weeks, and months passed quickly. The working hours in the workshop were very heavy, ten hours a day, and the heat in the summer months reached 38-40 degrees. For workers on the night shift, the working time was 12 hours. For students under 18, Saturday afternoon was considered a day off.

Adolescence in Devoll

The entertainments for adolescent boys were few, they did not exist; there is no comparison between yesterday and today, but perhaps it can be defined, in two words; “nothing is a lot”! The company’s library had eight hundred volumes on various topics, in the evening, twice a week, during opening hours, I was authorized to help Angelin, also a Friulian, to distribute and rearrange the books: and in exchange for this work, I could have all the books that interested me.

I read a lot and in a disorderly way, even books that I should not have read, for my young age. The romances that dealt with social problems of French, Russian, Hungarian writers, and poetry of Italian literature, were my favorite books.

At the end of 1939, many public service buildings, already unusable, such as; apartments, hospitals, and other buildings, were about to be completed, for places of rest after work, schools, churches, and residential annexes for the priests. The roads were paved and their connecting infrastructure, the place grew frontally, from behind, or, spread out on the surrounding hills. Dr. Rumo was the first doctor who was called to work in the hospital, and he gave the nickname “quinine,” the only medicine that was for all diseases.

Some Italian nuns, with the main one, Sister Paskualina, helped the doctor. Another teacher also came to the school, as the number of students had increased and the teacher Jolanda Silverio could no longer cope with her work with five classes.

Later another priest came to replace Don Criseri, of Piedmontese origin. Don Mario Morandi, from Bergamo, had come among us in Devoll, as a pastor and teacher. A cultured, wise, helpful man, a former officer in the war of 1914-1918, he had fought and suffered with his soldiers. After returning to civilian life, embittered and disappointed, he became a priest practicing apostolate in prisons and asylums.

In our parish, helped by his fellow citizen, Panza, who played the church organ, he had gathered many young people and created the church choir. Beyond what my religious beliefs may have been or are today, I consider myself lucky to have met him, to have been able to talk and discuss with him, a deep connoisseur of the human soul, he would kindly call me; “civilian protest.”

I don’t remember if it was at the end of 1940 or in the spring of 1941, that the medical lieutenant, Antonio Mandolin, was appointed as a deputy to Dr. Rumo, who returned to Italy for a period of rest. At the time of Dr. Mandolin, the service for Italian military personnel was established, near the hospital; he liked the environment, organized it, and with the help of the sisters, the reception.

He expressed the desire to make it possible and to offer his work as a civilian doctor, being a practically continuous job even with a second doctor, his name was proposed, and was accepted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and at the beginning of January 1942; he was regularly employed in the organic team of the hospital. He was born in Recanati in Marche, a very religious man, with a good sense of humor, always available to the poor, the unsupported, and the Albanians, good at his profession, he very quickly amazed and won the sympathy of all Italians and later also the Germans.

He came from a low origin, his father was a shoemaker, he had reached medicine through a scholarship. He practiced his profession in the spirit of a true missionary. He did not like the liberal profession, so that there was no risk of slipping into the love of money. He was satisfied with a salary, just to be able to live comfortably. He became a friend of the parish priest, Fr. Morandi, and periodically entertained the young people on issues of health, medicine, and prophylaxis.

Promoted by the company at the request of the parents, a three-year professional course began at that time. Some professors, graduates, and technicians of “AIPA,” showed their readiness to teach every evening three courses, to give the new young employees the opportunity to continue their education, which had interrupted their studies in the fifth grade of elementary school.

For me, this was an opportunity that should not be missed, even though, taking into account the working hours, the sacrifice was great. The weeks and months passed more slowly and monotonously, only the rhythm of the siren sounds that called for work. Whoever stamped the attendance card five minutes late, in the end, had half an hour of work deducted.

In the afternoon interval, on the street in front of the entrance, I spent a few minutes with friends to smoke a cigarette. One day I was surprised by my father; who gave me a rebuke that I have not forgotten! “Having a habit is not a sin, but the sin should not be kept!” I started smoking, a cigarette secretly; from time to time someone would give it to my mother, Silverio, in exchange for a small service.

The War

In 1940, the flow of Italian soldiers of all arms to Albania increased significantly. The big black clouds had gathered on the horizon. Four kilometers from the construction site, a military airport was built. On June 10, 1940, Mussolini, in an unforgettable speech, told the Italians; “the die is cast” and he joined Hitler, in a war that no Italian wanted. Italy, already caught up in the colonial wars in Ethiopia, Eritrea, from the aid sent in January to General Franco of Spain and then the invasion of Albania, did not have the means or resources to support a new conflict.

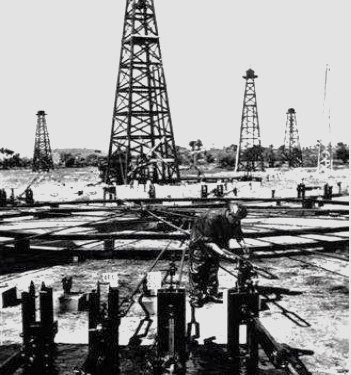

There was a lack of raw materials; there were no oil deposits in the Italian territory. At that time, we at the AIPA construction site, where I worked, produced a tenth of the Italian national oil demand. For local needs, a minimal amount was refined on-site, the rest of the production, with a 90 km long pipeline, reached the port of Vlora. From here, with deposits, crude oil was transported to the refineries in Bari.

With the start of the war, Devoll, entered the oil-bearing field, it had become a point of strategic importance. All the civilian personnel employed in “AGIP” were militarized. This new status did not cause, initially, great and unexpected changes in our lives, but we were subject to the military code and it was easy to predict the danger of enemy air attacks.

For about a year, our life passed quite calm and peaceful, we followed the bloody war with its ups and downs, through the news bulletins on the radio. Food items were not lacking, the flow of soldiers of all arms continued to increase, a clear sign that something big was preparing to explode, but in the period that followed, nothing happened to worry about, nothing was preoccupying that could ruin the dreams of our families.

Benefits (some) in favor of Italians abroad

The fascist regime, if it can be called that, was a “pink water” dictatorship and it is not clear if it can be compared to those of the communist parties. Some good laws in favor of workers are still in force today, and they were made during that period. Italians who worked abroad were respected and enjoyed some privileges; the children of immigrant workers, in the summer could spend a short time in Italy in groups as guests, in the mountains or at the sea. This policy was certainly not free, and it had demagogy and propaganda inside it, however, it gave me an opportunity to see Italy again, which I had the advantage of taking for two years in a row.

The first year I spent a month in Albavilla, in the mountains near Como. A camp organized in a military style, we slept in tents, ate the ration with bowls, the raising of the flag and the lowering of the flag, such as the salute of a 75 mm cannon shot. The responsible team in charge of the preservation had the privilege of loading and shooting it. One of the interesting aspects of these visits was the opportunity to meet other young people from different countries. The climate, the forests, the excursions, and the drinking of freshly milked milk in the stables should not be underestimated or forgotten.

The following year, if I’m not mistaken, was 1936, I spent a month in the paramilitary group of the Catholic naval organization. Depending on the age, the children were divided into groups like balilla, vanguard, etc. We ate food together in a canteen; a building with large dimensions in the shape of a ship that was divided into rooms for dormitories and showers. The sea baths and gymnastic exercises occupied most of the day, or as an alternative, we went to visit the surrounding area. In one of these trips, I visited the castle of Gradara, where the events of the tragedy of Francesca da Rimini took place.

The War against Greece

On October 28, 1940, the Italian army crossed into the Greek area of the border; at first, it seemed easy, they arrived up to Ioannina, but then they had to turn back. The Greeks, supported by the British, took up dominant positions in the mountains and showed a strong resistance; some strategic areas were lost and regained several times, with great heroism and the sacrifice of our soldiers. To make the situation more uncertain, winter came with abundant snow, our troops were still wearing summer uniforms, most of the food froze.

On the road from Berat towards the front line, the heavy Italian artillery was placed, the 149 mm cannons, their explosion could be heard every night; the distance that separated us from the front line of fighting was about 30 to 40 km. During the day, the warning sirens of the alarm were heard with a frequent frequency, but luckily our ‘G-50’ fighter planes were keeping a good guard and in some duels with the Greeks, they always had a bad time. A blockade was created at the front, which lasted for several months.

My mother was terrified, the alarms were frequent, and it was not easy to reach the shelter. My father had opened a big hole in the space located in the back of the house, covered with thick tiles, which could only serve for protection from flying shrapnel, but also to calm my mother who was in a state of nervous trauma, which was becoming much more frequent.

My father, who understood that the situation was getting worse, used his knowledge of the German language to ask the officer of the company command, who was in charge of supplying the nearby military airport, if he could repatriate the family, with one of the transport planes that arrived every day from Italy, with loads of materials for the army. Since my father was employed by them at that time, he gave him permission.

Christmas of 1940, was a sad Christmas, but we spent it with the whole family together. For lunch, we had also invited “master” Dariol. The next day, December 26, my mother, my sister Irene, and Albina got on a Junker plane, and in a two-hour flight, they arrived in Foggia, from there they went by train to Gemona. My mother later told me about the shocks of the flight. I was left alone again with my father; we met sometimes in the evening, when he returned from work, but the dinner, of course, was not like the one my mother prepared.

During the days of the week that I was at work, at lunch I would go to eat at the canteen, on Saturday afternoon which was not working hours, I had it assigned for cleaning the house, for washing clothes and underwear. Unfortunately, washing machines had not yet been invented! On Sunday I would go to meet and talk with Mrs. Maria and her daughter, Ulda, two Friulian women who administered the only hotel in the place. On the first floor, there was a bar and a dining room, while on the upper floor, bedrooms that at that time were occupied by the pilots of the army’s combat unit.

In January or February of 1941, (I cannot remember the exact date), when I returned home in the evening, I found on the table a bottle of white wine, two sausages in a piece of paper, and two words written in pencil: “Hello, Dad.” A few days ago I had insisted a lot to convince him not to accept the job that was offered in Vlora by a friend of his, but I had not succeeded, he had the blood of the nomadic instinct. In the spring Mussolini was for a visit to the front line; “I came, I saw, I won”, the fascists wrote, the others corrected; “I came, I saw, I cut the rope”.

To end this unnecessary war, the intervention of the German army was necessary, which pushed back the Greeks. The Greek campaign ended after six months, from May to June 1941, it had cost Italy 14,000 dead and 38,000 wounded. A small story, which does not appear in all school textbooks: the ship that brought back home the remaining part of the heroic Alpine division, “Julia,” was torpedoed by the British. Among them, the “Galileo,” which brought back home the “Gemona” battalion! /Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)