– The Confession of Vedat Kokona: 10 Weeks in a Room with Enver Hoxha. He Never Spoke to Me About Politics or Communism-

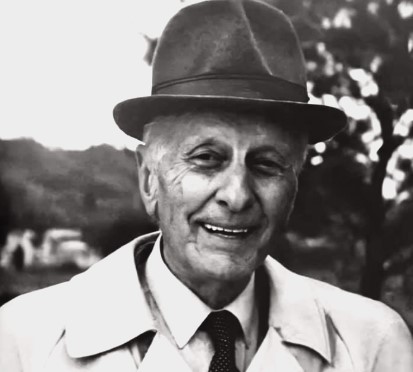

Memorie.al / Vedat Kokona, a prominent intellectual of the 1930s and 1940s-a poet, critic, translator, publisher, and professor-was forced to retreat into his “shell” during the dictatorship, abandoning all but translation. His former roommate, Enver Hoxha, turned Albania into a swamp, and intellectuals had to either disappear or compromise to survive. Kokona’s compromise was to dedicate him solely to translation and the creation of dictionaries, giving up all his other pursuits. Yet, his memories remained, and they are now being published by “Kokona” editions.

“Usually, memoirs are written by ‘great’ people, renowned statesmen, generals, and politicians with booming voices who gamble with the fate of humanity,” he writes. “With a single word carried by the wind, or a mere signature, they bring thousands of lives to the ground; they hold millions of people in slavery for fifty, even seventy or more years, and then history takes them as well.”

In his life’s memoirs, titled “Endur në tisin e kohës“ (Woven in the Fabric of Time), Kokona recounts his acquaintance with Enver Hoxha and the ten weeks they shared a room in Korça, where both taught at the French Lyceum. He also shares thoughts he likely wanted to tell Hoxha to his face but could not.

“The reader will not find extraordinary events here,” Kokona writes. “No heroic deeds. They will only find some events from which the fabric of time is woven-events that my country and I went through together during eighty years.”

Below, we have excerpted a few pages from the memoir of one of the most distinguished figures in Albanian letters.

Memories of Vedat Kokona, from the book “Woven in the Fabric of Time”

I left for Korça on the morning of April 14th. This time, I was going as a “professor” to the lyceum where, four years earlier, I was still a “student.” Since I had left early, I arrived in Korça around five in the afternoon, left my suitcase at my uncle Vehip’s house, and before going to rent a room where I had once lived, I went to the ‘Mazhestik’ café, which was also the city’s largest cinema, near the Vlach church.

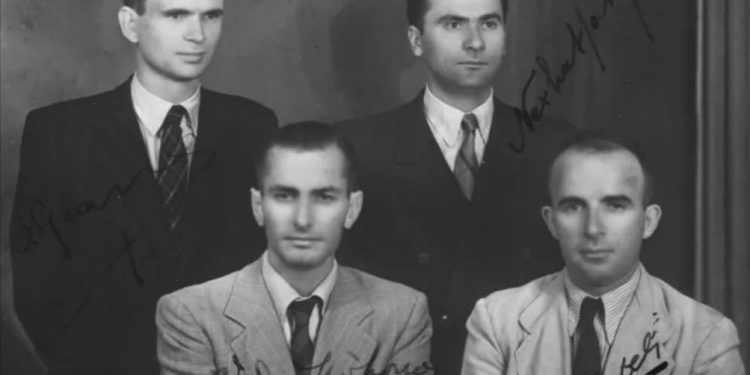

The weather was warm, and the tables had been set outside. There I met some old friends from the Lyceum: Fejzi Dobi, Fejzi Dika, Enver Hoxha, and Serafim, our Natural Sciences professor, who liked to hang out with Gaqo Gogo. A loudspeaker placed on a pole opposite us echoed the beautiful voice of Rina Keti, a singer who sweetly sang the song, “J’attendrai. Le jour et la nuit…!”

Enver asked me where I would be staying. I told him where I had stayed when I was a student. He said that if I wanted, he could set up a bed in his room at Polikseni’s house, across from the lyceum, which would benefit both of us since we could split the rent in half. His proposal seemed reasonable, and I accepted without hesitation. I picked up my suitcase from my uncle’s house and settled into Enver’s room. His bed was near the door, and mine was opposite, in the corner. The room had two windows; opposite them was the house of the Lako family. The daughter of this family, as I later learned, was a student at the lyceum.

From the very first night I stayed in his room-it was the second time we had slept together in a room, the first time in Paris, almost two years earlier, when I had sheltered him for two nights in a row because he was in a difficult financial situation-the fabric of our closeness seemed to thin a lot. He asked me what courage I had to take on such a task-to replaces De Courville in the French literature course for the lyceum’s advanced class, something that even Selman Riza himself would not accept. I told him I was aware of the importance of this burden, but as a former student of De Courville and not bad at French, I would try to manage this difficult task through hard work.

Our conversation that night ended there, and we went to sleep. In the morning, when I woke up, I saw Enver standing in front of the window, running his hand through his hair. I sat up a little and, leaning on the pillow with my right elbow, looked out my window in the direction of his gaze. On the balcony of the house opposite, decorated with flower pots, a young girl had come out, with a smiling face that shone in the morning sun.

“She is plump,” he told me. “She is my student.”

I ate breakfast and went to the lyceum, which was nearby, to the director’s office. The director was Kostaq Cipoja, my former Albanian professor for five years. He received me very well, and his demeanor gave me courage to perform the difficult task I had undertaken. I had the French literature course in the “Seconde” and “Premiere” classes. I knew what a mountain I had in front of me, but with willpower, patience, and especially hard work, I would be able to climb this steep path that awaited me.

One of the students who made a great impression on me was Kristaq Tutulani, whose composition I had highly graded. I told the students that I was not a “titled” professor but was there “malgré lui” (in spite of myself) to replace someone who was much more skilled than me at this job. However, I assured them that with their help, which they appreciated hearing, we would manage to “honorably” close out the two and a half months remaining until the end of the school year.

A day before the French professors left Albania, the lyceum’s administration hosted a farewell dinner for them at the “Pallas” hotel. As I recall, the attendees included the French professors with the technical director of the lyceum, De Courville, Kostaq Cipoja, Ligor Serafimi, Selman Riza, Fejzi Dika, Enver Hoxha, and me. The farewell speech was given by Selman Riza, an excellent former student of this lyceum ten years earlier and now an equally excellent French professor.

His speech, in perfect French, was met with admiration from everyone, especially from De Courville, who said he had to choose his words carefully to respond appropriately to Riza’s beautiful speech. We, who had known him for a long time, were proud of this rare educator who made us proud. Enver, who could not measure up to him, later imprisoned him for the sole reason that he was Albanian and not a communist.

A couple of days later, I had my “Premiere” literature class. I was going to talk about Molière’s “The Misanthrope.” I had brought from Tirana Lanson, the voluminous book on French literature, and Levrault, my favorite books since the years I studied them as a student. After dinner, I sat down at the table, which it seemed only I would use, as Enver never sat there, and I got to work. Enver, as was his habit, walked back and forth in the room with his hands in his pockets. Once he came up to me and, in his usual calm manner, said: “You are a great worker!”

“The work demands it,” I said and continued working. I remember he complained about his leg hurting. He even had a walking stick that he sometimes used.

One afternoon, I set to work correcting the students’ compositions. There were about 20 compositions to correct, and with four pages for each, it was a lot of work. On each page, I had to write my notes, and this was not easy: the students were used to the comments of De Courville, the French professor who was an expert in the field and not just anyone. I spent more than two hours on one composition, and Enver, who was walking around the room, said to me: “You have great patience! It is enough to glance at them and give the grade each one deserves.” “It’s just talk,” I replied and continued my work.

During those ten weeks we lived together, I never saw him work. He taught morality lessons in the lower classes of the lyceum, and he would spend hours reading the novel “Voyage au bout de la Nuit” by Ferdinand Céline. He never spoke to me about politics, let alone communism. If he was a communist, as an adherent of a doctrine for which others went to fight in Spain, he would have tried to win me over, a neophyte of this belief, because he was not afraid that I might report him.

I was with him until the middle of 1940. I am more than certain that he did not have in his head, until then, those evil ideas that would lift him so high four years later, to those dizzying heights from which he turned on those who had helped him and threw his relatives, friends, and especially the country, which had opened its eyes to him, into the abyss.

It seems worthwhile to dwell a bit on this figure, which is a sphinx to me, next to the pyramid built with the bones of those he killed: on this man who became who he became and who would not have become who he was, if things had not happened the way they did. More than once I have tried to figure out the secret of a life that cost the country hundreds of thousands of deaths. More than once I have said to myself: when the poor people, who did not know him as I and the few Gjirokastra students of the Korça Lyceum did, applauded and cheered for him when he appeared on the tribune, when the hall rose to its feet, hysterical and tragicomic, and screamed and shrieked like hungry jackals, when some, weak of mind and even more so of morals, shed tears at his death, just as they had shed for the other Asian executioner- more than once I have said to myself:

“How is it possible that he, one of the average students of the lyceum, goes to study Natural Sciences in France with a scholarship (another enigma, because scholarships were only given to excellent students), is not capable of completing his studies, fails the exams, has his scholarship cut, becomes a weak teacher, and later, a prominent statesman that history will remember?” I knew him as a good-natured, cheerful, and smiling person, so how did he become so wild, ominous, a monster?

To what height of arrogance and madness can power elevate a person, this “weakest reed of nature”? This cursed, hateful power gives birth to sultans and Neros, tyrants and despots – these monsters who enter history because of the blood they shed. One of these is, without a doubt, this man who threw the country into an abyss. Just imagine if God had sent to this beautiful land, which shines like a pearl on the shores of the Adriatic and Ionian, a great figure like the one He sent to Turkey on the brink of an abyss, Atatürk!

He came down from the mountains with a well-prepared army, with strong discipline, in the prime of his life, when the country was in great turmoil. Communists, Ballistë, Zogists, fascists, and Nazis had clashed and shed fratricidal blood, but now the latter three were no longer a threat; only the communists were in power. With a little sense and a few chosen people – because this small country doesn’t need many – and with love for the country and a lot of goodwill, in agreement with the West, this country could have entered the path of democracy. Instead of taking the turn that threw it into the abyss, it could have taken the other turn that would have lifted it to luminous heights.

But he chose precisely the path that reason forbade and that only vanity allowed. He did some good things that other potential governments would not have been able to do so quickly: not education-because Zog had done that before him and better-nor electrification, which would have happened under any government-but he did put the people to work. Many good works were done: swamps were drained, canals were opened-things that others would have done, perhaps a little later, but not with the whip of the Maliq camp and the death of prisoners. Hydroelectric power plants were built, but also bunkers that terrify you when you see them. The people had the tranquility of Zog’s rule, but they didn’t have justice. The notion of law, of sacred property, of the attribute “human” was lost.

Man was no longer human; he turned into an amorphous being, without character, without an ideal. He reached the point of hating his own country! Not just hating it, but cursing it! At a time when Palestinians fight for a handful of land in the Judean desert, the “new man” leaves his beautiful country and goes to beg for a mouthful, knocking on the door of a foreigner who greets him with contempt.

The Albanian whom great foreigners once admired is now spat upon by bastards who are no cleaner than those rascals who, to get a filthy visa, sell their honor and homeland. Albanians used to emigrate from their country, but they emigrated as gentlemen and after working for a few years, they returned as gentlemen and were not kicked out with a boot in the back. Emigration was an open door during the time of the “tyrant” Zog, when you could go anywhere in the world you wanted. But he, the evil one, locked this country in a filthy basement, in a polluted swamp where miserable frogs croak day and night.

Almost half a century in darkness, in misery, with deceptions, investigations, executions, internment, spying, where you went to bed in fear and woke up in fear; when your heart trembled when the door knocked; when you waited with frozen blood-when the Front cards were given out-lest your name not be mentioned on the list of the “chosen ones”- because this card was useless when you had it, but it caused a lot of trouble when you didn’t, taking not only you but your whole family down; when neighborhood meetings were held, where you had to speak and say what you didn’t want to say; when you got up at three in the morning to line up to buy a kilo of meat, with worms dried out and shriveled in the refrigerators for many years, or two bottles of milk, waiting outside in the rain until the saleswoman came; when you scrambled to get in line for cheese; when you returned home empty-handed because there was no more milk after waiting for hours…!

What pen, what brush, what symphony, will ever be able to convey that tableau of misery that gripped the wretched people and turned them into a submissive, hungry, humiliated flock?!

Neither Catiline nor Caligula can compare to him who held three million poor people in the most monstrous slavery for almost half a century! The generations to come will not believe that in the middle of the 20th century, there was a country in Europe that the sun did not reach, where the day ended and dawned in the deepest darkness of the centuries.

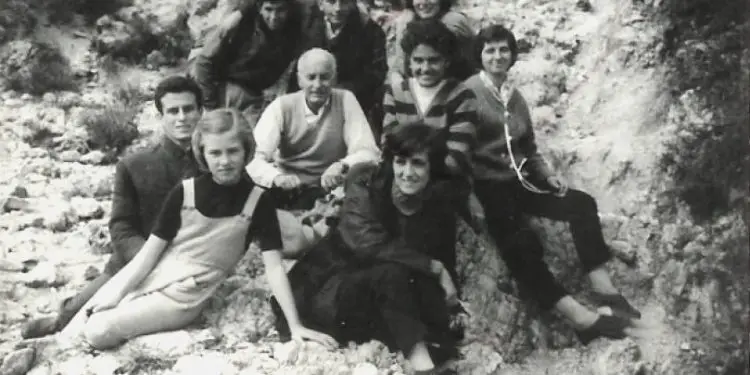

What were this disaster and this curse that befell you, O my Mother?! What fate cast you down in this way? These are the thoughts that come to me today, on a beautiful late August day, here in Piqeras of Bregu, with its turquoise water, clear as a teardrop, which would make even the most famous shores of the world envious if they saw it, even worked by the hand of man! I have seen many beautiful places in Europe and England.

From a young age, I saw Rimini, Venice, Stockholm, Lake Como, the Gulf of Naples, Sorrento, and Ischia. The famous coast of California or the Bay of Rio de Janeiro will surely be beautiful too. But our Ksamil is just as beautiful, which, even though it is bare as it is now, shines in its entire azure nakedness. And one day, when life is there, when sailboats glide on the crystal-clear waters, when the shores are lulled by the lapping of the Ionian waves, those who will lie there basking in the sun will remember me and prove me right./Memorie.al