By Dr. Ledia Dushku

The first part

Memorie.al / The relations of totalitarian regimes with intellectuals have often become the subject of discussions in scholarly circles. It seems like when this relationship is delineated in two opposite directions, where the intellectual must choose between being a “man of the yard” or a “dissident”, without having a middle ground. But in communist dictatorships there is the concept of the “art of survival,” which is nothing more than a combination of calculated submission, self-controlled criticism, tactical keeping of a low profile, and the quietly intelligent use of opportunities that may arise. In this way, accepting the social contract of the communist regime does not always make the intellectual a “man of the court”.

The article “Enemy of popular power” that scientifically “works for us”: the communist state and the researcher Eqrem Çabej (1944-1954), focuses on the relations of the communist regime with the linguist Eqrem Çabej, aiming to answer the question: How could a intellectual educated in the West, considered an “enemy of popular power”, to survive and further be valued in a regime where Marxist-Leninist indoctrination was at the root of everything? From a methodological point of view, the article is conceived in a chronological-thematic approach. The analysis has as its starting point the early intellectual formation of the researcher Çabej, in order to further understand the behavior of the communist regime towards him.

The presentation of the character in several perspectives, intertwined with the exposition of the features that “science” and “employee of the mind” acquired in Albania in the years 1945-1954, are in function of revealing the behavior of the regime towards the typology of the intellectual, represented by Eqerem Çabej ; to understand to what extent the state’s attitude was conditioned, since it is mainly focused on archival documentation. The documents of the Central Archive of the Republic of Albania, part of the funds of the Ministry of Education, the Royal Institute of Albanian Studies, the funds of the Labor Party (Structures and Leading Bodies) and the Prime Minister’s Office have been examined in detail.

Very important methodological support is the research in the State Security form file for Eqerem Çabejn, consulted at AIDSSH. With their help, the dynamics of surveillance, espionage, the impact these have had on the life and activity of Eqrem Çabej have been analyzed. A more favorable approach to the researcher of the legislation for consulting the archive of AIDSSH, would serve to fully realize what is known in scientific language as indirect research, thanks to which additional data about Eqerem Çabejn would be discovered from the files of the monitored characters, part of his family and social circle.

The full realization of this research would enrich the prepared profile and serve to understand more widely and deeply the dark side of the communist regime in relation to the individual / researcher in general and Eqerem Çabejn in particular. Aiming to deal with the researcher’s relationship with the communist regime in many ways, the oral history was also considered important, conveyed thanks to the memories of the professor’s daughter, Brikena Çabejt, who was very cooperative.

Who was Eqrem Çabej and what did he represent?

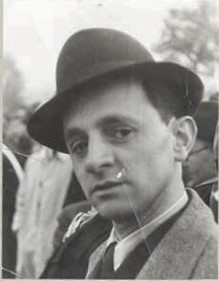

Eqrem Çabej was born on August 6, 1908 in Eskişehir, a city near Ankara (Turkey). According to his daughter, Brikena Çabejt, six months after his birth, the family moved to Gjirokastër, but; “father did not like to say that he was born there. In his school records, his birthplace is Eskisehir, but in every biography he called Gjirokastra as his birthplace, psychologically I believe. He never wrote that I was born in Eskisehir”. His father, Hyseni, a judge by profession, had left a mark on his son’s education, giving him an education, as Çabej himself said, “Directed by civic honesty and love for the country”.

The boy from Çabej finished primary and city school in Gjirokastër. After winning a scholarship from the Albanian state, in 1920 he continued his education in Austria, first in St. Polten, then in Graz and graduated in Klagenfurt. He completed his higher studies in Austria, namely three semesters at the University of Graz and five semesters at the University of Vienna, specializing in general and Indo-European linguistics and Albanian studies, in the classes of Professor Nobert Jokli, one of the most prominent Albanian scholars known at the time, as well as in the history of the Balkans. During the entire schooling period, Çabej showed will and perseverance and stood out as a young man who showed a lot of promise. Formation with the solid features of the scientist takes its starting point in this period.

Professor Jokli, appreciating his talent, kept him close. The relationship between them influenced Çabej’s love for scientific research and served as an impetus for the continuation of in-depth studies on the Albanian language, already with the doctoral thesis ‘Italoalbanische Studien’ (‘Italo-Albanian Studies’). The dissertation was defended on October 7, 1933, and Eqrem Çabej was awarded a diploma for the degree of Doctor, from the University of Vienna, with an excellent result.

For the above, the leading authorities of the university proposed him to stay there, as an assistant next to Jokli. But Çabej rejected the proposal, returned to Albania, thus fulfilling the commitment he had made on August 19, 1927, towards the Albanian state, with which he was “obliged to, after completing his studies, serve the State for 7 years, in each country that is sent or, to return the money received as a scholarship”.

Upon returning to Albania, Eqerem Çabej worked as a professor of literature and the Albanian language, first at the State Gymnasium of Shkodra and then at the ‘Normal’ of Elbasan, the State Gymnasium of Gjirokastra and the Lyceum of Tirana. At the same time, he also held administrative positions, such as that of the sub-director of the “Our mountains” dormitory in Shkodër and the head of the secondary education section at the Ministry of Education.

According to the report of the directorate of the Shkodra High School, the professor of Albanian literature showed a liberal attitude in his relations with the students and respected their opinion. Establishing a relationship of trust was considered important, and in this respect lying was not easily chewed by him. Although the high school directorate stated that due to his young age, he lacked the spirit of sacrifice, it highlighted the fact that Çabej “inherently contains elements of improvement and conviction”.

He stood out for his correctness, professional preparation and national feelings: “He is very good and always tries to study; I always have a blank face. He didn’t miss school. There are good feelings of nationality”.

Thus, the consolidation of Eqrem Çabej as a researcher of literature and the Albanian language on the one hand and folklore on the other hand began rapidly. The publications of a series of articles in “Hylli i Dritës” and in various international magazines stand out, without overlooking the book “Elements of Albanian language and literature”, with selected parts for secondary schools, published by the Ministry of Education in 1936 This activity classified Çabej as one of the most vocal intellectuals and educators in Albania in the late 1930s.

The Second World War found Eqerem Çabejn director of the Tirana High School, a position he did not hold for long. The reason is revealed by the report dated July 27, 1940, of the Tirana Fascio Federation, in which Çabej was considered “the only person responsible for the bad actions committed by the students of the Lyceum, in the well-known demonstrations of November 28, 1939. Until today has not shown any sign of rapprochement with fascist politics. Therefore, it should be considered dangerous and measures should be taken to dismiss him from the duties he is currently performing”. In January 1942, he was sent “as a semi-internment” to Italy, where he stayed under supervision until June 1944, working for the Albanian Linguistic Atlas, at the Academy of Sciences in Rome.

Meanwhile, in appreciation of his scientific work, Eqrem Çabej, since April 1940, was the youngest member of the “important” [regular] age and part of the Governing Council of the Institute of Albanian Studies, reorganized in August in 1942, as the Royal Institute of Albanian Studies and in April 1944, as the Albanian Institute for Studies and Arts. At the second meeting of the Governing Council, on April 14, 1940, when the rapid preparation of a summary on the state of studies carried out by Albanian authors and from other countries on Albania and Albanians was discussed, Eqrem Çabej was appointed one of the two editors of part of the Albanian language, together with the Italian researcher, Carlo Tagliavini.

But his relationship with the Institute was not linear. It was broken in 1942, when the work commissions and sub-commissions were reorganized. In addition to being appointed to the Linguistics, Terminology, Folklore Sub-committee, Çabej was also appointed a member of the Dictionary Sub-committee, which included Father Fulvio Cordignano. On September 27, 1942, he sent a short but courageous letter to the head of the Institute, Ernest Koliq, with which he requested; “remove me from the list of members of the Institute of Albanian Studies”, that; “as a [member] of this Institute, there is Father Fulvio Cordignano, whom I really don’t even know personally, but is universally known as a strict enemy of the Albanian race”. The resignation was not accepted, under the reasoning; “that his name is eternal as according to the Statute”.

During his stay in Rome, first the Italian authorities in 1942 and then the German authorities in 1943, proposed him the post of Minister of Education, in the government of Tirana. In both cases, the answer was negative. Çabej himself has expressed that; “I rejected the two proposals for cooperation with foreigners, as something that did not agree with my Albanian honor and the good of my country and people”. Without avoiding such a reason, I think there were two more reasons that influenced the negative response. The first reason is related to the fact that Çabej did not consider it important to engage in politics.

In the telegram that the German diplomatic representation in Rome sends to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it is evident that; Çabej had rejected the post of Minister of Education, under the reasoning that; “he doesn’t feel he’s qualified for the position of minister and he also doesn’t want to engage politically.” In addition to the culture received in the family, to stay away from politics, the fact that in the period of Ahmet Zogu, civil servants and teachers were forbidden by law to be involved in political activity must have influenced his protection.

The second reason, which must have led Chabej to reject the post already, proposed by the Germans, I think is related to the tragic end that the Germans gave to his beloved professor, Nobert Jokli, who was killed by them, while they also disappeared his personal library. This opinion is reinforced by Brikena Çabej, who confidently says that her father; “he could not accept to become the minister of the Germans, who had killed his spiritual father, Joklin”.

The news about the murder of his brother, Selahudin, who was the sub-prefect of Tropoja, was, according to family members, the reason for Çabej’s return to Albania. Upon his arrival, in July 1944, he began temporary work in the Ministry of Education, in the Commission of School Texts (Superior Inspectorate). Meanwhile, Çabej continued to fulfill his commitment at the Institute of Albanian Studies and Art, participating in the meetings of the Language and Literature Committee.

This relationship continued until May 1945, when the Provisional Democratic Government took over the direction of the Institute of Studies and appointed Selahudin Toton as its manager. Tanimë Çabej was appointed a technical officer and during the years 1945-1946, he directed the work of the group, for the preparation of Albanian language files, for the terminology of natural sciences, which included Sabiha Kasimati and Gjergj Komnino.

Features of science and “employees of the mind” in the first years of communist Albania

After the Second World War and the establishment of the communist regime, Albania entered a new phase of political, social and economic development. The state structure and the Albanian society would have to be developed on completely new bases, which had no meeting point, with what had happened in Albania earlier. Exceptions from the whole, would not do study fields and “employees of the mind”. Since the second meeting of the Democratic Front, on October 7, 1946, Enver Hoxha considered the issues of education, culture and science, the most important problems of the Front and the State.

Already in what in the terminology of the time was considered as “New Albania”, whose path was marked by the National Liberation War, the development of education, culture and science would take on profoundly different features than before. They were dictated by the new model that the Albanian state and society would have to follow. As for culture / science, Hoxha stated that; in general, it had to be developed on a scientific basis, to be cleansed of “all reactionary ideologies that are in flagrant opposition with the great principles that emerged from the National Liberation Movement”. On the contrary, it was considered “anti-historical, anti-human, a lowly servant and a vile weapon in the hands of reactionary cliques”.

As in other fields, the model on which Albanian science would rise was the Soviet one, considered as a vanguard. Albanian science, like the Soviet one, had to be based on a unique worldview: the dialectical materialism that constituted the philosophical basis of the doctrine of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. She had to be; “at the service of the working masses” and protected by party spirit. In function of this spirit, the political color that culture/science had to take was its basic component. Science could not but have ideological content, and for this, as Manol Konomi, head of the Institute of Studies, said, researchers should not have the slightest doubt.

The above features were also decisive for the features that the researcher and his work should have. First, the “employees of the mind” had to recognize the new social reality and cut off any “unbroken connection with the old world” and “bourgeois science”. The method of their work would have to be the Marxist-Leninist one, without which they could not benefit from the science and culture of the peoples of the Soviet Union. The acquisition of this method was connected with the recognition of the “new worldview”, of philosophical and dialectical materialism.

Men of science had to get out of the realms of idealism, where they had been pushed by “reactionary regimes of the past” and descend into the realm of reality. They had to be connected with the people/masses at large. Now the freedom for the researcher (for) was limited only to the right to know the aspirations, needs and problems of the people, openly avoiding the freedom of thought and judgement.

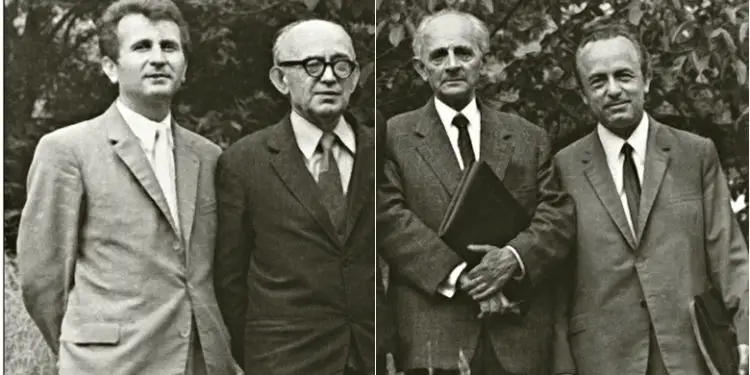

All of the above would also be the lines on which the work would have to be developed in the Institute of Studies, newly created by the government of Enver Hoxha, on January 28, 1947, with a name changed to the Institute of Sciences, a year later after. One of the 23 members of the Institute was Eqrem Çabej. Now the attitudes towards the Royal Institute of Albanian Studies and its activity will start to become more politicized and more negative. The attempts to stigmatize this institute as an organization created by the Italian fascist invaders, in the service of their policy for the Italianization of the Albanian society, are getting stronger.

The communist state and the researcher Eqrem Çabej

The first 10 years after the establishment of the communist regime in Albania would be difficult for Albanians and intellectuals in particular. The regime would seek to consolidate and, as a result, would develop totalitarian propaganda and terror. As in other totalitarian regimes, terror would be carried out through a blindly obedient and well-disciplined police apparatus.

There was no other party, except the party-state, and any opposition or opinion against the ideological line of the party was severely punished. In addition to the thirst for power, terror was also exercised by the tendency to create the “new man”, who had to be worthy of the communist society, considered as perfect. In this context, work with the elite/intellectual became important.

The focus of attention on the process of shaping new elite, considered as such not because of age, but because of ideology, took special importance even for the communists in Albania. The new elite, in addition to the part that would be newly created and educated in the Soviet Union and the countries of people’s democracies, meant the reformation of the elite/old cadres and mixing with the ideas of Marxism-Leninism. In the terminology of the time, “old cadres” were considered those who had studied in the schools of the West, who from a cultural point of view were under the influence of that school and under the possession of “bourgeois ideology”.

They were without a party and as such, had ideological and political problems. The old elite that did not agree with the form of the regime that was being established, was considered by Enver Hoxha and the most vocal Albanian communist leaders as a potential danger. As such, it had to be “reformed” to cooperate with the regime, otherwise it was considered too dangerous and had to be marginalized. Memorie.al

The next issue follows