By Aldo Renato Terrusi

The ninth part

Accueil

Memorie.al / Fiumicino Airport. Alitalia’s ‘MD 80’ plane is ready for flight. It’s Saturday, November 6, 1993. 11.25am. The commander received approval. The flight attendants remind us once again to fasten the seat belt. The two engines are brought to maximum power, while the noise becomes muffled and deafening. Buttons and controls are tested one last time according to flight procedures, the brakes are released, the faster and faster movement begins, the acceleration slams the passengers into the back, the plane takes off. I feel an invisible force lifting me up that leaves me suspended in the void. I look around to see if the other passengers have the same feeling as me. Some read, some look out the window, some are indifferent, some barely sit still and some, frozen in their seats, let their fears show. With a wide change of direction, the plane rises in altitude and heads towards the radio beacon of Bari, then straight to Tirana, our destination.

In Durrës, they took us to the silo I just saw, which was used for storing goods. We may have been a hundred people, gathered like sheep, crammed into circular beds; we went and bought food in the poor shops near the port. We were left with only two allaturka toilets, one for women and one for men, and in the morning there were long queues; some would get up and go at night just to avoid the morning line. We lived in those conditions for almost two weeks. Every day they lied to us, telling us that the ship would come during the day and that we would leave, but such a thing did not happen and thus the disappointment was repeated. Very soon we ran out of money and I had to go and ask my friends in Tirana for some gold coins. I don’t know how, but I was picked up by a truck driver who knew my father, and that’s how I got to the city in a few hours. I went to my friend Demneri, who lent me some money. My next problem was getting to the ship in time.

At the time I was in Tirana, the ship that was supposed to anchor in Durrës had changed its course to Vlora. Suddenly an order came that all immigrants would be moved to the port of Vlora, with several trucks made available by the Albanian authorities. The oppressive immobility that had gripped all those long days of waiting suddenly turned into a feverish movement. Potions, screams, people being searched for among the self, children not being found, luggage not being locked, noises of all kinds to merge into a general confusion. Immigrants were rushed, pushed, stepped on just to be the first to get on the trucks, and they were so afraid of not finding a place or worse, being left without a ride. It took a long time to get everyone settled. Around 20.00, a cold and clear night with stars, the convoy of trucks started to move, a long, rambling and noisy snake in the direction of Vlora,100 kilometers of winding road full of potholes. I don’t remember much, I was very young, but some ephemeral moments have remained indelible in my memory. One of these is the image of swaths of headlight light shifting, crisscrossing, ascending and descending in the dust kicked up by the wheels of the trucks on a journey that seemed to never end. My childish imagination was struck as, wrapped in a blanket and sitting next to my mother, I surveyed that fantastic landscape of light and shadow that seemed accustomed to dancing monstrous creatures.

“The convoy of trucks arrived at dawn and stopped on the pier next to the ship with the lights still on. The port guards tried to get the people and loot off the trucks as orderly as possible. Their new homes would be the warehouses of the port. Upon arriving in Tirana, I went to the President of the Albanian Federation, a certain Kristo Papajani, to whom I explained the situation and asked him for help to return to Durrës, because the ship could have arrived and could have left without me. He told me that he might have some motorbikes available. There was a possibility that someone could accompany me, because there was a race going on those days. He called one of his motorcyclists – who later turned out to be a true friend – and gave him tollons of gasoline to go from Durrës.

“When you go to Italy, send me some dessert with cream, you know I’m very picky”!

“I will definitely send you, I will not forget. Thank you”!

The bike was ready, but since it was a racing bike, there was no rear seat, so I had to adjust on the fender. It took almost two hours to cover about 40 kilometers from Tirana to Durrës, through those notorious potholed roads. Upon arriving in Durrës, a bad surprise awaited us: the ship was no longer in port and we found only garbage in the warehouse. Not even a shadow of that fleeing people. After the first moments of shock and bewilderment passed, we started asking around: we were told that the immigrants had put them in trucks during the night and taken them to Vlora, where they would then put them on a ship straight to Italy. We hit the road again. I took a cardboard that I saw among the garbage and put it under the buttocks that were not catching fire, on the fender of the motorcycle.

In Vlora we saw the ship that had finally arrived and luckily had not yet left. But I still couldn’t spot my family. We had learned that the Italians were stationed in the warehouses of the port. My family had come to Vlora together with the others; therefore they had also left the port. I asked him for information up and down and finally we found them sheltered in the house of an Albanian carpenter, who had worked in Vitaliano’s company in Kuçovo. I gave my companion almost all the money that Kristoja had lent me. He returned to Tirana and we were once again in touch. The carpenter accommodated us in a large room that was simply his workshop. We slept on the mat. We also informed our friends, Major Verdi and Captain Taliani, former civilian carabineer who had not yet managed to return to Italy, about the imminent departure. The ship was stationary, waiting for a load of coal to start the engines. My rear was still burning from the way I had done sitting on the motorcycle fender and I was only getting by with cold compresses. We didn’t even have money to buy bread, so I decided to go to the house of some of my hunting friends; one of the eyes had a grocer who was doing well, he lent me a gold napoleon and gave me a good handful of snacks: cornmeal bread, sheep’s cheese, olives and salted fish.

“When you go to Italy send me material for saçme”.

“Thank you, I won’t forget it.”

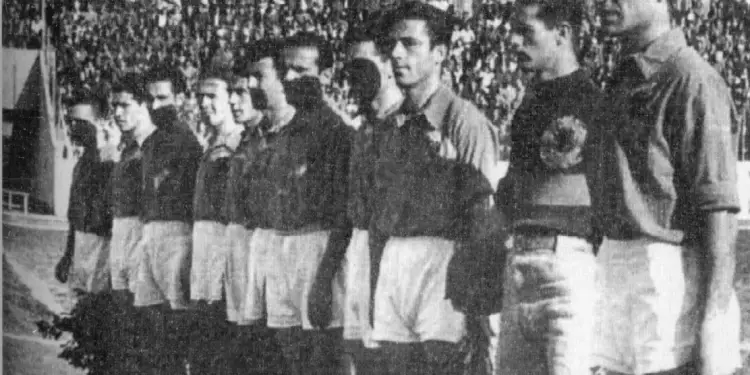

Before we left, they let us wait another two or three days. At first light in the early morning, the sailors began to move to the bridge deck for the necessary maneuvers, the engineers loaded the coal, while the pressure of the boilers increased, the first plumes of smoke rose from the chimney. The ship was leaning slightly on the opposite side to the bench; the boat, with all its lumps, was rust-black, the superstructure was death-grey, it had only one cylindrical smokestack, the two masts were held by ropes corroded by sea salt, the cranes loaded the coal into the two stacks of bash and pupa, the iron bridge was cut off like some mountain path. Only its name, ‘Stadium’, on the bash, appeared to have been painted over recently.

In the warmth of the first rays, the ‘sea carriage’ guests waiting to board were showing some impatience.

There wasn’t a drop of wind, but the skin felt damp and salty, while a thin band of fog began to spread, unfolding the horizon around us. Finally, the order to board the ship arrived and the appeal began among those who were to embark. They asked us if there was anyone who knew Albanian well and I offered myself as a translator, especially for the Italian ex-soldiers who were being repatriated. Slowly, the emigrants climbed the steps that led from the bench to the ship, and only by mid-morning, the boarding was complete.

The bridge was completely occupied by a crazy mess of legs, heads, suitcases, blankets and still cradles, mattresses, crates, toys…! Now the ship was about to raise the anchor, a cloud of black smoke with a pungent smell of sulfur flooded the environment”.

My uncle’s story triggers a particularly vivid memory of mine. After we boarded the ship, I looked around curiously at everything around me, I wanted to go at all costs to the railings, and my grandmother very carefully accompanied me there: I pulled her with force, overcame the obstacles spread over the bridge, avoided them, until I ran to flag arrow and got ready to see the sea. For the first time I saw its bottom and I was amazed: the water was transparent like crystal and the ship floated, casting its shadow towards the bottom. An unforgettable memory. Algae bushes were growing on the sandy bottom, fish were swimming in half depth, shells were also seen on the rocks, but the thing that impressed me the most was when I saw a large twisted rope at the bottom of the sea that resembled a snake.

“From the rusty deck ladders, the Italian sailors advised us to stay calm and without speaking, not to start the celebrations for the departure in any way – at least until we leave the Albanian waters – because there was a possibility of a possible incident. Two former Italian soldiers, Major Verdes and Captain Taliani, were not given permission to leave. When it was finally my turn to board – I was the last one as I had also done the job of translator – I was stopped by a customs inspector whom I knew, but who didn’t even greet me, on the contrary, he ordered me to be checked again and more detail.

He wanted to see the photo album I was carrying with me and he showed me some of the pictures I had taken during the hanging of Faslli Frashër, the head of the National Front and a member of Enver’s political group, but whom they considered a traitor. However, I managed to hide and save at least some photographs, which I keep to this day.”

From the speech of Enver Hoxha on November 28, 1944 on the occasion of the commemoration of the declaration of Albanian independence of 1912:

“The traitors of our country, Mustafa Kruja, Mehdi Frashëri, Ali Këlcyra, Mithat Frashëri, Abaz Kupi, Shefqet Vërlaci and all the other collaborators used all the ways to divide our people; their demagoguery was not noticeable and in the beginning, a part of the people was lied to a certain point by these thugs, blind instruments always ready to serve our internal and external enemies. The organizations of the National Front, Legality and all other terrorist organizations, became active weapons of the invaders and with unheard of ferocity, they attacked the people together with the Germans, massacring innocent women, old people and children, committing theft and rape. ..”! “The sun was very high in the sky when, slowly, the ship began to leave the port of Vlora. The strain of the propellers in motion seemed to be aided by the force of thought of the passengers: walk, walk, and walk! With gasps and gasps under the cadences of vomiting, swaying on the waves of an almost calm sea, the ‘carriage’ was falling from side to side towards freedom. By early afternoon fatigue had taken over and an almost unbelievable stillness reigned on the ship, broken only by the roar of the engine. The flat sea and the clear sky were the same color; wherever you turned you couldn’t make out the horizon line. The ship seemed lost in infinity and a certain deep anxiety of loss and fear began to make room among the passengers.

Where are they taking us, where are we going like this? The captain and the crew members, who were Italian, managed to pacify the people: keep calm, we are going home! There, in the dusk, the lights of the coast of Brindisi could be seen in the distance. Someone started shouting: Italian land, Italy, Italy! And a wave of excitement swept through everyone’s hearts. The ship passed along the host waves of the pier and slowly entered the channel between the red and green traffic lights. A tugboat came in front of us and escorted us to the jetty.

The light was blinding because many projectors were shining at us. At the harbor pier, only guards, soldiers and protective nets awaited us… maybe we were prisoners in our homeland? They helped us to descend calmly, under strict supervision. Who laughed, who prayed, who cried, who kissed the ground.

They separated us: men on one side, women on the other. Your mother asked me not to take my eyes off her for a moment, as the confusion was immense. I held your hand tightly. We were ordered to undress and lie down; the clothes would be given to us later, after we passed through the disinfecting showers. All naked, children and adults, we entered a large space from which a cloud of steam was coming out. We gave him a warm and pleasant shower. Only after we were cleaned and dressed again were we allowed to meet our relatives who were waiting for us behind the railings of the harbor entrance. I, you and your mother were taken by Giuseppe’s sister, Kiarina, in Kastelaneta, while all the other relatives were sent to a refugee camp near Lecce”.

THE MEETING WITH PETRIT

“Okay, uncle, maybe we should go now, Toli and the driver are waiting for us.”

-“Let’s drink something refreshing and head again towards Vlora”.

The road becomes more damaged, with many potholes, often deep and with many detours. Along with herds of sheep, oxen and the occasional pig, we encountered very few cars, but mostly people walking, loaded with various items, and many young Albanians dressed as soldiers advancing along the roadside. . A horse-drawn cart, heavily loaded with people and fodder, slows down our journey even more. Late in the morning we finally arrive in Vlora. The taxi driver, according to Toli’s orders, stops right in front of Petri Velaj’s ground floor house. Petriti, with whom we have been meeting for several days, is waiting for us to arrive early in the morning. As soon as he sees the taxi, he approaches us with a serious and restrained look. He is a thin, small man, with hair still gray at the temples and almost gray on the forehead, wearing a Tyrolean hat. His face is scarred, but youthful, with small black eyes, sly and sly.

He is wearing a brown jacket and a pair of dock trousers, a light blue shirt with a green waistcoat and a blue tie, suede shoes. It would look almost elegant if it weren’t for the slightly excessive combinations of clothes that almost went out of fashion. We introduce ourselves with the usual greetings. The apartment is a pleasant villa with a small courtyard, surrounded by other houses built without a point of urban planning. Petriti, leads us to get comfortable in the living room, where we notice a round dining table with dark walnut wood, above which a Liberty-style plaster statue triumphs, and four upholstered chairs around the table. In one corner two armchairs covered by a quilted cover with an oriental design and the corresponding table on which there was a vase of artificial flowers, a dresser with a display case in which the plates and glasses are pointed out, a chest opposite the armchairs and near the window again two wooden chairs. The furniture is complemented by some floral prints with thin frames, hanging on the pink walls, recently painted.

-“My friend will make you a coffee and then I will accompany you around”.

A woman enters, old, brunette, in her sixties, in traditional dress: she wears a black skirt, with wide sides that reach her ankles, with a white shirt heavily embroidered, over a space of flowered clutches, a pink blouse with half sleeves and silver buttons, on her feet colored cloth slippers and on her head a white scarf covering her even blacker hair. It looks like it came from a postcard from the 1800s. It doesn’t speak, just a nod and a shy smile. Another wave of greeting and just as it came, it was gone. Vlora appears to us at its best, illuminated by a beautiful sunny day. We cross the main road that leads from Petrit’s house, towards the central square of the old town. After arriving there, we see on the left a fountain, while in front of us raises the building of a bank, a brown three-story building with a solid appearance of classical-colonial architecture. On the ground floor, there are bank offices with large windows protected by railings. My parents used to live there on the first floor and I was born there.

The only thing that had changed over the years was the large white sign above the main entrance of the building – which during the years of the Italian occupation, was: BANKA KOMBĘARE E SQIPNISĖ, while now it is: national bank of Albania, the look is more worn and decadent, apparently it has not been repaired or painted since our family was expelled from there in 1945. Equipped with a special permit and accompanied by a local guard, not to mention the whole family of the caretaker, we enter the offices on the ground floor. The bank is empty; we don’t even see employees, let alone customers. We don’t even ask why. I remember many stories of my mother about the events that happened in this country, I can almost see them.

On October 12, 1943, the Bank of Vlora was surrounded by a group of twenty German soldiers, who got out of two vehicles. From the first vehicle with chains, five soldiers and their lieutenant got off, who with harsh manners and with weapons in their hands opened the way between two Albanian guards of the security service, forcing them to raise their hands up, not to move and not to some joke The lieutenant asked to see the director and treasurer. My father and lawyer Beluci appeared. They were openly asked to hand over all the money in the treasury together with the gold reserves that were in the deposit. My father replied that he was not authorized to make such a request and together with the lawyer, they put handcuffs on him. Immediately after that, the lieutenant together with his soldiers began to intimidate the clerks behind the counter, ordering them to open the safes and throw the money into the bags; of course they could do nothing but obey. The double keys were handed to the lieutenant and a clerk was made to accompany the two soldiers to the depository and open it. They found very few gold napoleons there.

The Italian Central Bank, even before the armistice of September 8, had transferred a part of the gold to Italy, while another considerable part had served to finance the Italian industries which, since 1939, supported by the regime, had been settled and worked in Albania. The German lieutenant, very angry, threatened the father with death, accusing him of treason, then threw off the handcuffs and took him away in one of the vehicles. Then came the mandate to check the apartment on the first floor, where Aurelia and the maids lived. While some soldiers took up positions, others climbed the inner stairs. The maids tried to prevent them from the entrance by holding the door, while Aurelia ran to the bedroom where, under the closet, in a crack in the floor, she had hidden the gold sterling that her husband gave her whenever he found it on the table of eating a dessert made from it. She put the coins and some ornaments as fast as she could into a cloth bag, ran to the window, and threw them all over the bank’s perimeter wall into the yard of her parents’ cottage next door. Memorie.al