By Lek Pervizi

Part seventeen

THE ODYSSEY OF INNOCENCE

To my brother Valentin, who endured?

47 straight years of the ideological storms of

communism, moreover, separated

from his wife, a true Odyssey

in the middle of the twentieth century.

Memorie.al / When you enter Skuraj and cross the Urdhaza stream, the mountain climb begins, on the hill called of the Lekbibajs. You pass in a row the three mills known as Gjin Pjetri’s, which rise one after the other. You also pass the two-story tower of Ndrec Pjetri, Gjin’s younger brother, and then you encounter a rocky ridge on which stands a complex of three stone buildings, the historic towers known as the towers of Gjin Pjetër Pervizi of Skuraj, the leader of the Kurbin uprising. These buildings dominate the entire valley, which is formed by the confluence of the Mat and Fan rivers (a tributary of the Mat), up to Milot. It is almost a fortress, which protects and defends the area from the expeditions of foreign invading armies that could penetrate through that gorge, until they met the wall of the Skuraj Mountains, where the towers we mentioned were erected.

Continued from the previous issue

An Endless, Headless Wait

The news was given to Gori with great care by the Ministry, through the Officers’ House, where Valentin had served and where he was still officially listed as effective (as a prisoner of war). However, despite the care shown by the responsible officer, the news had shocked Gori, and she had fallen into a depression, where she had to be hospitalized for a few days. Her mother had passed away, as well as her brother and three sisters. Only one was left, quite wealthy, who took care of her. Valentin found out about this much later. The Embassy would never have been able to get such information. But it happened that a free friend of ours, who needed a document for his sister who was married in Italy, and was allowed to enter the Embassy, the ambassador himself had asked him if he knew anything about a Valentin Pervizi.

The friend, who knew us very well, had told him that Valentin was being interned without hope of release, in Gradishta. This friend worked and lived in Lushnja and since I sometimes met him, he told me about the Embassy, where they had asked him about Valentin. Valentin’s spiritual state had worsened. This apparently affected his health. Around 1974, while returning from Lushnja by bicycle, he had fallen due to a dizzy spell. This had consequences and he was forced to go for a check-up, where he was immediately hospitalized.

The doctor of the ward happened to be Dr. Çabej (the brother of Eqrem Çabej), a friend of ours, who found that he had something in his lung and absolutely had to be hospitalized in the Sanatorium of Tirana. Since he needed the permission of the Branch, which might hinder that work, the hospital took it upon itself, reporting to the Branch that the so-called Valentin Pervizi had to be hospitalized urgently in the Sanatorium. So they took Valentin to the Sanatorium with the hospital ambulance. The director and surgeon was Prof. Ndroqi, who knew us well. After the check-up he did, it turned out that Valentin had something like a wound in his lung, and he absolutely needed to be operated on and was asked to accept and sign for that intervention.

He signed. The operation was successful. It was a process of an encysted echinococcus. A part of the lung had to be removed, to ensure against the spread of an infection. So Valentin stayed hospitalized for about a month in the Sanatorium. His health condition improved completely. Meanwhile, the political situation was dire. The Chinese Cultural Revolution also affected Albania. The dictator had entered a health phase where he could barely stand. He had suffered one or more heart attacks. He was consumed by a kind of mental decay.

This gave his wife, Nexhmije, the opportunity to be over his head and lead the political affairs, with the support of Ramiz Alia. Meanwhile, serious events had occurred, such as the executions of Beqir Balluku, Petrit Dume, and others. Then the killing of Mehmet Shehu (which was declared a suicide) and the arrest and sentencing of his supporters. The execution of Kadri Hazbiu and company. The Ramiz-Nexhmije couple had opened the way for themselves, to continue to hold the state and the party in their hands. The tool was Nexhmije, and Alia carried out the work.

A way out was sought, because it was seen that the communist system was in complete failure, both inside the country and outside it, in the sister republics, where the waves of anti-communist protests began, which ended with the killing of Ceaușescu and his wife, in Romania. This instilled fear in the Albanian communist rulers. All the more so when the invasion of foreign embassies began, by thousands of dissatisfied citizens, who were seeking salvation from the Albanian communist hell. Not only those who had been branded as reactionaries, but even the communists themselves, were forcibly sheltered in the embassies.

So much so that Perez de Cuellar himself was forced to come to Albania, and impose on the government, the permission for the refugees of the embassies to leave, as well as the giving of passports to the internees who were held in labor camps, and to the families branded as reactionary and declassed. In this context, the Security played a big role, sending hundreds of its agents and spies abroad, to keep the situation under control inside and outside the country.

But at the same time, returning to Valentin, a hope opened up for him that he could benefit from being reunited with his wife in Bologna. As we mentioned, their correspondence became more regular, and his wife also sent some packages, as well as dollars. She expressed the desire to come to Albania herself, since the doors of freedom had opened. But Valentin advised her not to take that step and to wait for him in Bologna, where he would come himself. If his wife had come, where would he take her, to the Gradishta camp?!

It would have been good, for her to know the miserable conditions where her “Ulysses” had lived and worked. With the order to issue passports, the Internal Affairs Branch of Lushnja had notified the internees to get their pictures taken for the passports. Thus, Valentin, along with us and other internees handed over two photos each to the Branch. The Branch would issue the names in order, for the collection of the passports.

These began to be given out for a while, and then they were blocked again. The acrobatics of the Security officer, assigned to this work, began. With 100 dollars, you had a guaranteed passport, but you had to find a person, a friend of that officer, without whom you could not get the passport. 100 dollars at that time had great value. With 400 dollars you could buy a house in Tirana. What to do, what not to do. We found a friend of ours, an internee like us, but who had a great friendship with his brigade leader. He, in turn, had a close friend in that officer. So with 100 dollars, my wife, my two sons (the third was a soldier in Himara), and I got the passports. Valentin found out and was annoyed. “I won’t give a single penny. It’s their duty.” He did not accept that bribery.

We managed to leave in October 1990, for Belgium. We left instructions for that friend of ours, to get Valentin his passport as well. With our departure, Valentin changed his mind and gave the 100 dollars. Thus he was provided with a passport. They gave him the visa immediately, at the Italian Embassy. But what happened?! Going up and down in the winter, from Gradishta to Lushnja, several times, until they gave him the passport, he caught a serious cold and was bedridden for a couple of weeks, with penicillin and streptomycin.

It was as if fate was following and torturing him, to prevent him from the last trip, to his “Ithaca” of Bologna. On February 20, 1991, precisely on the day of the fall of the dictator’s monument, he was at the airport, to board the plane for Bologna. The big demonstration in “Skënderbeg” square for the overthrow of the monument had been heard everywhere. Valentin became afraid that an incident might occur and the trip would be suspended. Here, it seems, fate gave up its evil ways and the plane took off. After two hours, Valentin was descending at the Rome airport, where his Italian “Penelope” was waiting impatiently.

He gets off and looks here and there; he can’t distinguish his wife anywhere. He goes and sits in a corner of the waiting room, looking outside, thinking that Gori might have been delayed or might have mixed up the schedule. On the other side, his wife was also waiting, because she had not distinguished her “Ulysses” among the passengers who got off. When the place was empty, she saw that man who was standing on the opposite side, with his back turned, looking outside through the windows.

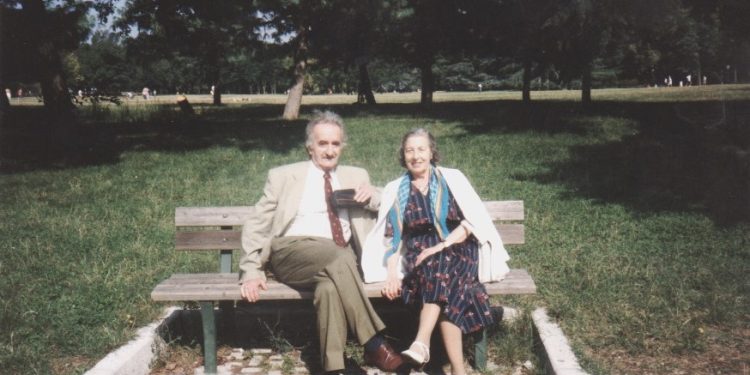

She approaches slowly, close to the person, and with a half-voice she spoke: “Scusi Signore, lei non è per caso Valentino…?” (Excuse me Sir, aren’t you by any chance Valentin…?) Valentin turned: “Gori”?… and they hugged, after 47 years, now as old people. This “Ulysses” of the twentieth century had surpassed Ulysses of 3000 years ago, because not for 20 years, but more than double the time, he had to face the storms and waves of the ideological seas of communism, to be able to hug his beloved, who had been snatched from his arms, at the most beautiful age of youth. And now after 47 years, they managed to be reunited, to the point that they barely recognized each other.

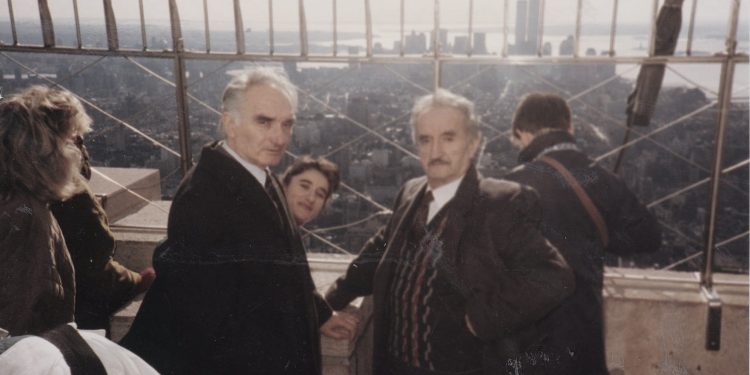

The only difference was that “Ulysses” Valentin did not find his palace occupied by the suitors of his “Penelope”. There was no need to show who he was, nor to fight against them and eliminate them. The reunion with his wife created a period of peace and mental relaxation for both of them. They felt the absence of a child, a “Telemachus”. Fate had not been big-hearted, to leave them two old people, lonely. Under these circumstances, we went to Bologna several times. Then we took Valentin to Belgium. We visited Paris, with its monuments and Royal and Imperial Palaces. Mainly the Louvre, to admire the masterpieces of world art and Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

Amsterdam, to get acquainted with the works of Rembrandt and Van Gogh. With Valentin, we also went to America, to New York, where the wife and children of our brother, Genci, who had died on the eve of the collapse of the dictatorship, had settled, and an uncle of theirs had brought them there. So Valentin had the opportunity to enjoy something from the free world, from which he had been hermetically isolated for 47 years. Where such a tragedy lived in conditions of endless and headless punishments has not been seen or heard of, and where Valentin was labeled as an “enemy of the people” who would be hard-pressed to gain freedom one day.

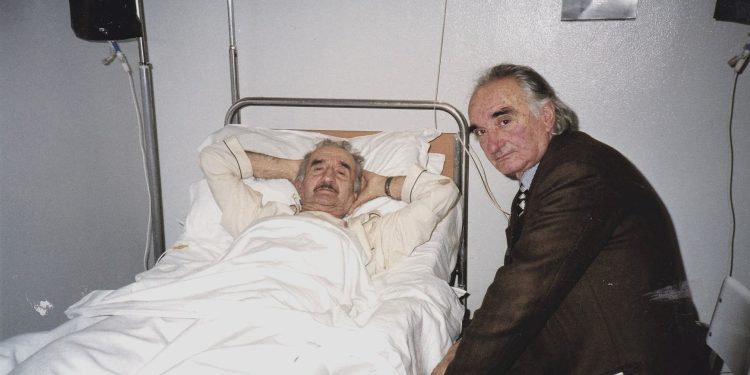

This was the conclusion of the Italian ambassador in Albania in 1967, to which the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs had requested information about Lieutenant Valentin Pervizi, as we showed above. In the conditions of the freedom gained, Valentin began to write his own memoirs in several notebooks, with the aim of publishing a book. But seeing that his health was failing, and after a difficult operation, he handed me all the notes he had lined up, with the request that I complete them for a publication.

A job that I am doing. The disease worsened and he remained hospitalized in the Sant’Orsola and then Malpighi hospital in Bologna, where I stayed by his head, for four months straight, until he died, on March 4, 1999, at the age of 79. As sick as he was, unable to get out of bed, one day he turned to me: “Listen Lek, as soon as I get better, we’ll go to Albania together and fix some things…!” His wish was unrealizable, but at least, the hope of recovery kept him going. At his funeral, the officers of the neighborhood where he lived and those of his regiment participated. His story was known, and everyone showed him, as long as he lived, honor and respect, and in the Officers’ House, they called him General.

As long as he was alive, he had made the request for the building of his career and the elevation to the ranks that belonged to him. The opinion was that he could be recognized with the rank of general, since he had been in effective service, until the moment when the command itself had released him from service (like all other officers), in the second armistice with the Germans. The time in Albania as a prisoner under the dictatorship was recognized as a prisoner of war. But nothing was done, as long as he was alive. Two years after his death, the decision to recognize the rank of lieutenant colonel came to his wife.

Those of his command were surprised and expressed an unjust decision, that Valentin should have been recognized with the high rank, as a general. He had given proof of his military abilities and was called an (unproclaimed) hero of the Battle of Tivoli near Rome, on September 8-15, 1943. As well as a prisoner of war, in conditions of punishment with prisons and concentration camps. A unique case, in the history of the Italian army, which deserved more attention from the high competent authorities.

To Gori, now a widow, we stayed close in every circumstance. She did not agree to come to Belgium. She was very attached to the memories of the family, which had lived continuously in Bologna and with the presence of Valentin, and her departure from that city seemed like a disregard. In the last year, when she was very sick, she had called my wife to stay with her. Thus my wife, stayed by her side for almost a year, until the last day, when she died in the hospital. In the hospital, there was no free bed, and since she wanted my wife close by, my wife slept next to her bed, on the floor, where she had spread some cardboard.

The hospital director, when he found out and confirmed the situation himself, stated that this woman deserved to be declared a heroine. Time does its own thing and so Gori, this “Penelope” of the twentieth century, passed away, to be reunited with her “Ulysses,” Valentin, in the eternity of Paradise. This was the novel lived by this couple, a true Odyssey of Innocence.

This was the whole story of Valentin, worthy of strong pens and film directors. We gave it simply as it unfolded, without exaggerating with elaborate descriptions. We believe that the reader will be emotional from this painful story, which reveals the criminality of an inhuman dictatorship, which brutally oppressed human rights even in the private life of people, by not allowing them to live and enjoy it.

Fate was merciless towards Valentin, involving him in a very long and sad journey. A journey not through waves and sea storms, but of unspeakable sufferings and miseries. During 47 years, he had to face communist terror, which stole an entire life from him. When he was arrested, he was 24 years old, and when he was released, 70 years old. Meanwhile, “Ulysses,” who had gone to the Trojan war at the age of 20, returned to Ithaca at the best age, 40, where Penelope, still young, beautiful, and faithful, was waiting for him with open arms.

Meanwhile, the other “Ulysses,” Valentin, would meet his “Penelope” after 47 years, at the age of over 70, where the tragedy that had gripped this unfortunate couple is very clear. A cruel fate that destroyed their lives. To know the communist hell, which brought all of Albania to its knees for half a century, reducing it to a miserable state, it is enough to follow Valentin on that long journey, which brought him to those hellish caves, where thousands and thousands of innocent beings were stacked and suffering.

In his imaginary journey, Dante met various characters, condemned to Hell for their sins, crimes, and faults. Meanwhile, through Valentin, we get to know real characters, stained with the acts of killers, committing crimes of every kind, against defenseless human beings. The paradox lies in the fact that these sinners and criminals lived in their earthly Paradise, while the good and innocent people were locked up and thrown into the caves of a real and ominous hell. As for Valentin, Mandela’s 25 years were not enough, but were almost doubled, to 47 years, an entire life.

Nelson Mandela had the right to be visited in prison by ministers, parliamentarians, journalists, politicians, etc., and to attend university studies and graduate there. Meanwhile, a few hundred Mandelas of Albania, with 45-year sentences on their backs, no one dared to approach them, let alone make official visits, talk and write in newspapers, and even less continue universities and earn diplomas in prison conditions.

So Valentin, not only could no one dare to come to a meeting with him, but he himself if he had approached closer to the barbed wires of the camp’s fence, was in danger of being shot and killed by the weapons of the cruel and criminal guards. He escaped a violent death, but not the countless sufferings and difficulties that were a true Calvary on such a long and tiring journey, which he completed with such difficulty, but at an age that no longer promised anything better. Memorie.al