By Eugjen Merlika

The third part

A life under dictatorship

Memories of a “class enemy”

Continued from the previous issue

Memorie.al/ Years later, surprisingly, I received a letter from my grandmother from Italy. She showed how she had tried in every way, using all her knowledge in the higher instances of the Italian State and of international organizations, to draw me there to continue my studies, but to no avail. After many attempts, a French journalist approached him and asked: “Madam, I have seen you often in these offices, what is your problem”?! My grandmother had explained my case. His answer was: “I am very sorry, in any country of the world I would have had the opportunity to help you, only in Albania I cannot. There is no possibility of communication. “Do not get tired in vain.”

My departure from school made a great impression on my classmates and teachers. They all went to the uncle at home, to express their regret. I am very grateful to all of them for their generous and courageous gesture, which unequivocally expressed a form of protest against the blind violence of the merciless regime. They did not know him, but the decision of my departure for them was unacceptable, in relation to my behavior towards them.

Now I had to deal with arm work. I was weak in body, but I lacked willpower. The father worked in the farm workshop as a turner. His honest and quality work was appreciated by his superiors, through whom I was able to find a job in Farm Investment as a construction worker, not to be an agricultural worker. There I had my friends, peers or older, with whom we were united by the long journey of common suffering, deprivations, unrealized desires, sincere friendship…!

After a few months, together with my parents, I went back to the Pluk sector, always with my family in exile. Already life had little change; days, months, years passed the same. The forms of class warfare that weighed on us were of the most varied. They also appeared in insufficient housing, which was never resolved in my forty-seven year life. I have always lived in self-built huts with reeds and mud. I slept in the bachelor’s room for three years, since we only had one room, in which my parents slept, we ate, we stayed, and we waited for a rare friend who remembered to come. Another form was isolation, the pressure on those around us not to give in to us, a racism before which Soveto is not worth mentioning. How many people were paid to “watch” our lives, who came, who spoke to us, who greeted us, who did us some good.

To feel like a stranger in your own country, without hurting anyone, is a condition I do not wish on anyone in the world. Such was our condition that dragged on for decades, with tides and ebbs, as after the whims of “Zeus”. Difference, hatred, infidelity were planted and cultivated in all directions, everywhere, in the social circle, but also in the relatives, within the family, up to the interventions in love relationships. We had no right to love girls of other social backgrounds or to think of connecting life with them. The communist “rifle aristocracy” had borrowed from its swordsmen the mentality of preserving the caste by mixing blood. The few cases of breaking this “major” law of Enver Hoxha, had their consequences with the permanent separation of parents from children. How many silent tragedies this way of action has caused in our country, how many wounds still unsealed in the souls of boys and girls who saw the violence of the regime dictate, through its pressure, the laws of the heart…!

After two years of exile, this measure was suddenly lifted. When this was officially communicated to me, a “i” was added to my name on the back, which changed the sex. Perhaps some kind in those organs of violence may have thought to give “freedom” to a nineteen-year-old girl, whose parents are in exile. So I happened to be formally outside the circle of my friends, who held the measure of internment and for several five years without separation, while I would meet with him again, but I will talk about this later.

The second half of the sixties brought further aggravations of the class war. All the nonsense of the so-called ‘Cultural Revolution’ of China was copied, such as appearing in front of collectives to present the biography, leaflets, Albanian dazibao, where theoretically “anyone can write without fear and in large letters, he goes crazy for work and for people”. The struggle for the demolition of churches and mosques was given, a barbaric act, unprecedented in modern society, with devastating consequences for the spiritual world of Albanians and for the destruction of cultural and artistic values that stood in places of worship. The fight against the Kanun was widely discussed, thus removing the foundation of some of the traditions and moral laws that had ruled this people for centuries.

The “emancipation” of the Albanian woman was bent too much, to put her completely in the dizzying gears of an idea, seemingly progressive, which burdened her so much that she deserved the definition of “slave of modern society”. The popular “heroism”, embodied in funny figures like Fuat Çela, was propagated with art, putting in service the official art, to create a whole generation of slaves, capable only of working as animals for the state, because only there will to find “happiness”. The channeling of all the desires and interests of the youth to work was the core of the strategy of creating the “new man” who was to be a robot in whose brain was only the “works” of Enver Hoxha. The attempt to change human nature through the violence of its laws could have no end other than failure, and could not better prove the folly of its authors.

Brezhnev’s theory of “limited sovereignty” flourished in the Eastern Bloc, later Czechoslovakia was attacked and Albania withdrew from the Warsaw Pact. Anarchy continued in China and the consequences were felt here as well. An honorable atmosphere was created, to which was added the work of the hafis, who tried to capture pieces of conversations to record in the personal files of the Security archives, in anticipation of the countless processes of agitation and propaganda of the seventies.

At this time, in the years 1967-1969, I completed compulsory military service. We mobilized to fulfill the Party’s message: “Sew to the hills and mountains to make them as fertile as the fields.” I was assigned to the Burrell N.B.U. With the uniform of a soldier, we had the task of deforestation and planting potatoes in the mountains of Martanesh, Lura, Stebleva, etc. I, with my craft of masonry, after five or six months, started working in the housing construction department of the Corps, as a result of the initiative taken at the country level, to build housing with voluntary contribution. I completed my military service without a single shot being fired, and to this day I have never fired a gun.

The Prague Spring of 1968 was temporarily a “ray of light” in the darkness of the Socialist Camp. My whole generation still remembers with great longing the names of Dubcek, Smerkovski, Chernik, etc., which became dear to us, synonymous with a new era, which nurtured our hope that the hour of change could come in the world as well ours. But unfortunately, August 21st overturned all the illusions of my generation that continues to honor the memory of Jan Palash’s heroic gesture. The logic of the tanks restored that order of things which was based on violence and the suppression of personal and social freedoms.

There, during my military service, I met other friends. In my memory remains the image of a poet, whom I called quite talented. Talent was associated with an objective and accurate outlook on life and a strong and positive character. Perhaps these were the reasons he did not recognize the podium of success like many of his colleagues. I remember how one cold December day, in the woods, by a fire where we had baked potatoes, he read me two poems he had written about Shkurte Pal Vata and Skanderbeg. The subtexts of the poems were very deep, bold and new for the time. I liked them very much and after an open conversation about them, he made some small changes and took them for publication.

I had a sincere friendship with him, which was not well received by his military colleagues, some failed poets, above all spiritually. In the name of art and the desire to “save” my friend from “infection”, they convinced him that I would be arrested and temporarily separated him from me. This caused a state of tension in me, but thankfully it was the last months of military service. Later my friend and I explained and we became friends, but I have not heard from him for many years. I am sorry that he was talented and with a big heart I foresaw a secure literary future for him.

The first years of the seventies were the quietest. People on the beaches listened to Hit parades together with songs by Celentano, Milva, Iva Xaniki, Massimo Ranieri and other Italian singers who, in general, were the ones they liked the most. Young people started to dress differently, girls discovered miniskirts and pants, and boys lengthened their hairpins. Foreign music and sports were openly discussed. But in 1973, suddenly, on the stage of Albanian society, the storm of the war against “foreign performances” began. At first it was remembered that it was simply a matter of appearance, but the regime had a much deeper aim. Pressure had to be used to avoid in the embryo any tendency to detach or question official dogmas and ideology. Terrible years of anxiety followed, with ups and downs. Ministers and high-ranking officials, accused of treason, flew, but the sword fell hard on us, who had only the trowel in their hands.

In 1974, at the age of thirty, I married a young girl who, contrary to popular belief, agreed to live her life with me. She just finished high school that year and we started life together, in trouble for housing, but hoping for a quieter life. We thought to build that life on the fruit of our honest sweat and, above all, to find solace in family harmony. I remember only one beautiful ten days on the beach of Durrës, and then black clouds covered it, warning of the storm and an endless winter.

Related to that difficult period are the memories of my uncle’s daughter that we had raised in our home and had as our child. She continued the first year of high school in Lushnja. It is unimaginable for the civilized and currently unbelievable world and for our youth, for a ninth grader to be expelled from school just because a friend of hers showed her in class a magazine page depicting a woman in beach clothes bathing! This was the “sacrilege” that the Pedagogical Council and the party organization would find as a reason to break the wishes of the two girls, who were still not well developed, to continue their studies.

Thus was fulfilled the “plan” of the victims of the ideological and political war against “foreign performances”. This was the official version of Silva’s expulsion from school. The truth was another, as dramatic as it is common in the criminal system in which we lived: The state security had wanted to make Clara, the girl’s mother, her accomplice. Her objection to doing the spy work they, responded to the order to expel the girl from school. That order was carried out by school leaders, who took upon themselves a crime: that of punishment by denying the right to continue the schooling of an innocent child. I would be curious to know if this fact has ever bothered them in itself, or it has been passed simply by justifying the implementation of an order that came from bodies that had nothing to do with education…!

I must honestly state that for me it was a deep pain for my sister to return to her parents in Gradihtëte and at the age of fifteen to pick up the pickaxe to dig the ground and make a living. I remember that tears escaped my eyes, when very rarely in my husband’s life, even in deaths, did I shed tears.

In 1975 the dismissals began. As part of the fight against bureaucracy, my friends and I, high-ranking construction specialists, moved into agriculture as field workers. This was the logic of Rrapi Gjermeni, who, in order to supplement the number of “bureaucrats” removed from the apparatus, as after the orientation of the Central Committee, included our names in the list of abbreviations. The economic damage to the state was obvious. We had carried weight in the construction brigades with our conscientious and skilled work, and suddenly these brigades were truncated. The remarks of the engineering-technical personnel in this regard were opposed by the “class war” in the name of which these measures were taken, and for which no one could object. This was one of the small evils compared to what awaited us in the years to come.

In March 1975 Kurt Kola, a friend of mine, was arrested. That six-year period of anxiety began. “Better a poor horse than no horse at all.” I do not remember now to whom these words belong; but during these years I and my camp friends, and of course their families, have fully proved the accuracy of the expression. Every three months, one of us was arrested in different sectors of the Lushnja farm where we were distributed. It seems to me that something are tightening my throat and not letting me breathe and now that I remembering those horrible years. Every day when we left for work we greeted each other quietly with the people of the house that, perhaps, we would not return to dinner.

It was an exhausting torture to think that from one moment to the next the irons could be put in your hands, to separate you from the bosom of the family. The worst thing was that you did not know how to avoid evil. The processes were done for agitation and propaganda, and this definition was so wide that they could blame you even without opening your mouth at all, just look out of the corner of your eye at a burnt bread or a rotten tomato on the seller’s counter. Here they found ground to activate the scum of society, people of no value except the vileness that, voluntarily, they put in the service of evil, to sow the despair of individuals, families, children, the whole society.

There were among them friends of ours, whom we called good people, friends of suffering from childhood, people whom we respected, waited for and went home to, but who, unfortunately, had returned to our gravediggers. The provocateurs found different ways to carry out their duties, and we turned dumb. Everything that was talked about, from the cultivation of the land, to the tools of the field, to the brigadier, to the music, to the film, to the goods of the shops, to the various services, everything that was said was engaged in hostile activity.

Therefore the only conversation without harm was sport and especially football, which we discussed for hours, without moving on to other topics that had become untouchable taboos. We did not dare to go out in the city lest we “stand out”. The problem was the case of deaths or weddings in society, where many people gathered, because a word said without purpose could be reported within a few hours elaborated by several people.

For years I did not go to the cinema once with my wife. We avoided meeting friends; sad loneliness was our only normal state. We followed with wide eyes every “Gas” that passed on the road and especially the plates 6701 and 6702 which were made for us as swallows that swallowed people. Anxiety engulfed the entire sector when they came with Security officers inside. Who was next in line today? This question like a grave fell on everyone’s brain and only when the car left, breathing was released. The situation became tragicomic if we took into account that everyone had that anxiety in their soul and did not dare to express it to anyone, not even the friend next door, not even the family members themselves…! Meanwhile, months and years were spent swallowing our friends in the black prison. After Kurti, Ahmeti, Eqeremi, Qemali, Fatmiri, Naimi, Mojsi, Deda, Leka…!

Already anxiety had taken another form of torture. Fear of arrest was compounded by destructive pressure in all its forms, to degenerate and become accomplices in crime, to spy on and accuse a friend, relative, or even a blood relative. It was the activity of the State Security, of the lords of this country, who enjoyed all the privileges, diligently served these privileges and those who had been given them. Facing the war with them required composure, experience, determination, and above all strong character. People of weak character surrendered in this war, to escape their evil they planned the destruction of the comrade, his imprisonment.

It was a fierce war waged against the conscience of the people, it was an attempt to destroy fundamentally everything positive that the soul of the Albanian had, and in the first place the trust and hospitality. It was an earthquake that shook the foundations of the nation and created a vertical rift that went to the depths of consciousness. The national character was deprived of the force that had made it face the storms of history together, discord, hatred, war between each other were sown.

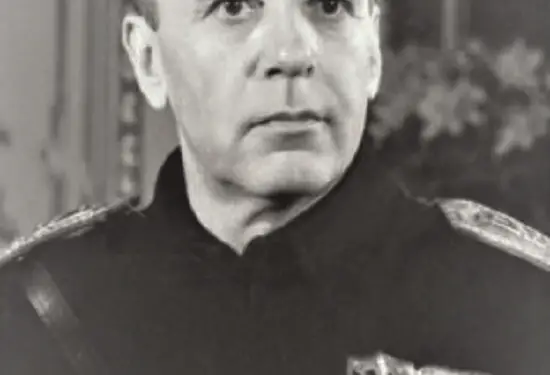

This pressure, which for years conditioned my being, I decided to avoid with an extreme decision: to accept the arrest and its consequences for myself and my family. Lija home three elders, wife and two little girls. In the hand of God! The arrest was made on April 25, 1980, at work. The “Gaz” of the Branch came with six people, officers and police. Even today, those women from Lushnja who worked there in the stables of the Institute still remember that scene. The Chief of Security, Kosta Ndini, asked me: “You are the nephew of Mustafa Kruja”? To my affirmative answer, he returned it with the usual formula: unfortunately, I remember Mrs. Roland’s famous expression before the guillotine: “People! How many crimes are committed in your name … “! Memorie.al

The next issue follows