By Altin Raxhimi

Part One

Memorie.al / The last of three reports shows the Albanian roots of the Jewish chief cleric of Athens, how the Jews of Vlora take him; “I will take the couple…”, after religious ceremonies and the fate of the Jewish family with the surname Tepelena. On the morning of July 2, 2016, enduring the heat amidst sweat that was pouring down, over two hundred people packed the synagogue here in the center of Athens. Five girls from the Jewish community of Yaniot, were to have their ceremony of transition to adolescence, the bat mitzvah, which according to tradition falls somewhere between twelve and thirteen years of age. After that, they would be young ladies. Four of the girls came from Jewish families from there, and one had come from the New York area, with family and relatives.

The synagogue rabbi began the singing of prayers. He is only twenty-six years old and the women of the community whisper to each other how to find him a bride, but without any apparent success. He has left behind his daughter from America. The synagogue on Melidoni Street is over a century old. With the transformations that Athens has undergone, this street, not even a hundred meters long, is like a pocket.

It used to overlap the area where the leather industry and the houses of the merchant class of the early twentieth century flourished, above Monastiraki and Thisio. Now on the right below, you see the excavations that brought Roman Athens to the square, and on the left, crumbling plaster painted with graphite, after the bankruptcy of those industries in the eighties – a haven for immigrants from the Middle East, second-hand shops and blacksmith shops.

Not even a hundred meters above Melidoni, is the northern part of the district, from where the Acropolis can be seen from expensive cafes. At the entrance to the road, concrete blocks blocking car traffic, at the entrance to the synagogue, a checkpoint like those attached to embassies. The ceremony continued under murmurs and whispers in Greek, and some in English, passing through it and something in Albanian. They were from the Kohen of Albania, a tribe that in 1990, all moved to Brooklyn, New York. The ceremony would be held for Reveka, the daughter of Elia Cohen.

After the rabbi’s blessings, the fathers would give the blessings to the daughters. Elia began the congratulations for his daughter in English, but then said to the audience, “Now I will congratulate you as our grandfathers congratulated us in their time. (Hóma na piánis ma hrisáfi na génete)”. Which means, “May the soil you touch become gold”. “At that moment, there was no one left in the synagogue without tears in their eyes,” recalls Zanet Batinu, director of the Jewish Museum of Athens and cousin of the Batins of Albania. Batinu’s daughter was also at the batmitzvah.

“My grandmother couldn’t help it. Not only because she hadn’t heard that old greeting for a long time, but also because of the way she said it, how she pronounced it in the old dialect.” In standard Greek, the verb “to be made” is pronounced “ginete,” but Elia Cohen spoke in the old dialect of Ioannina. “It was organized by Gabi, Gabriel Negrini, that rabbi there,” says Nesim Cohen, Reveka’s uncle, who attended the ceremony. “He wanted to bring the community together, to get to know each other.” Who knows how many times this name comes up!

I first encountered the beginnings of this search last spring, from the most elegant author on the Jews of Greece, an eighth-something, now retired near the synagogue I revived in Chania, Crete, and Nikos Stavroulakis. Stavroulakis has written a mesmerizing book on Thessaloniki – an essay on a collection of photographs from 1910, which showed a city erased by time. Filled with Sephardic shopkeepers and porters and dervishes of the Tariqa. That book turns that city into an elegy. “But I don’t know much about the Janjots,” Stavroulakis tells me on the phone.

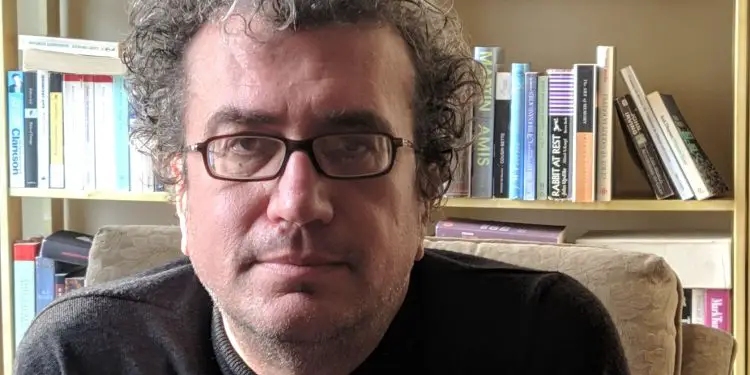

“Ask Gabriel, Gabriel Negrini who lives in Athens. Tell him I took you.” A Sephardic rabbi from Sarajevo, a thorough expert on Judaism, not just the Balkans, takes me there, to Gabriel Negrini. Negrini began his studies in electronic music in Crete, but it was there that he discovered religion and two years ago he became the rabbi of Athens and all of Greece, in this synagogue that dates back to the early twentieth century. And the news was picked up and even reported by the American Jewish newspaper ‘The Forward’.

Now, his photo on his official website is with a kippa a homburg and tefillin. He is involved in researching Jewish music and experimental music. He knows how to blow the shofar, the ram’s horn used during the Jewish High Holidays, he is a mohel (ritual circumciser), he has a very good voice. He has completed theological studies in Israel. “He has activated the community”! – Allegra Matsa from Ioannina tells me. “He is able to engage the young. The previous rabbis were old and old-fashioned. “Meh”! (“Look”), – writes Moses Elisafi, the cardiologist who heads the Jewish Community of Ioannina.

“Rabbi Negrini is from Albania.” When sometime in the twenties Josef Negrini from Ioannina left his wife Aneta a widow, she spent most of her time with the married daughters of the Jews of Vlora. From the thirties, his eldest son, Mojzja, came along, whom in Ioannina as a child, had sold newspapers. From the sixties, Aneta left the country and joined another of her sons, who lived in Israel, but Mojzja, who was also active in the cultural life of Vlora, retired as an accountant in the Social Food Trading Company, the company that supplied the city’s restaurants.

And Mojzja had a son, Fito, and Fitua, sometime in the twenties, married a neighbor of his in the palace in Vlora, who came from a well-known Orthodox Christian family from Mifoli – one of her aunts is a well-known child psychologist in Tirana. Fito and Greta Negrini, first gave birth to Reveka, who is studying to be a dentist in Athens, and in 1988, three years before they packed up for Greece, where Mojzja had a brother, they gave birth to their son, Gerion. Gerion is Gabriel, Rabbi Gabriel Negrini.

“Does he know Albanian”? “As I know Greek, in bits and pieces”, – Nesim Koheni tells me. “He prefers not to speak it or listen to it”, – others tell me. I tried to contact both Fito Negrini and Rabbi Gabriel, but I couldn’t. They mentioned security problems. “After 1990, it was one thing for the Janjiot Jew who returned from the concentration camps, another for the one from Halk who escaped the Holocaust, and another for the one who came from Enver Hoxha’s Albania”, writes Marie-Elizabeth Handman, a French anthropologist who studied them at the time.

Albanian Jews got along much better with those of other religions, who were given Pesach chicken, and who did not drink during Ramadan, but were initially more reserved and conservative. On the other hand, for the most part, Albanian Jews are like other Albanians and do not care about religion. When Andon Meloja, the child born from the first marriage of a Jew to a non-Jew in Albania, asked to register with the Jewish community in Athens, where he lives, three years ago, they surprised him. They wanted to take him to be circumcised.

“I said, ‘Are you kidding me? “I am an eighty-three-year-old man,” says Meloja, a retired engineer, Greek from Delvina on his father’s side, Jewish from Delvina on his mother’s side, married to an Albanian of Muslim origin, living in Fier during communism. But like other Jews, they show great solidarity with each other. And in Israel, a good part of the non-Jewish spouses, or children born to non-Jewish mothers by Albanians, have converted to Judaism, a longer and more arduous process than converting to Christianity or Islam. “Albanians are different in Israel too,” Matsa tells me. They have done it before many other Jews settled there.

Some of those who went to Israel or elsewhere in their old age had a hard time. Pepe Kantozi, who died in the nineties in Karmiel, mourned the social circle he had left behind. “When I went to Vlora, my father would call me on the phone from Israel, he wouldn’t ask me how I was or how I was doing,” says Zhaneta Solomoni-Jakoel, “but what he was doing, how Baçi was doing, what Xhevoja, Ruzhdiu and Kudreti were doing, how was Shazja…”, his friends from “Rruga Justin Godard”. “But even from the first generation, there were those who succeeded and took good jobs, the ones they had left in Albania”, says Gerion Kureta.

“Then the second generation, the one who was born there, exploded. They had unprecedented success”. Especially after the nineties, many people started to come back to visit. Shemo Solomon, with whom I first contacted to gather the experiences of Albanian Ioannina Jews, visits Vlora every two years, where he has also bought a house. Every year, Zino Matathia, the doctor who tells you that he was conceived in two placentas, one from Albania and one from Israel makes a pilgrimage to his apartment in Tirana. When he saw a Serbian Jewish girl living in Israel appear on television in 1999 and say that she was ready to go and fight in Kosovo, he volunteered at a hospital for Kosovar refugees that the Israeli army had set up in Blace.

When she moved to Ioannina with her husband and daughters in 1990, Zhaneta Jakoeli cried for six months straight because she missed Vlora. Now, the television in her apartment in Ioannina is tuned to Albanian channels, and when she returns from Vlora in the summer, she brings a suitcase of Albanian novels with her, and on both visits I made to the Jakoels, she often turned the conversation to literature. “Even when Albanians have bar and bat mitzvah parties,” she says, “like a few years ago in America, they say, ‘I’ll get the couple, I’ll go hunting!’”

Nisim Cohen recounts the memories of his mother and father from Brooklyn, supplementing them with books written about Ioannits and Jews. Anna, his dentist and cousin who left in her youth and brought her people to New York, is perhaps the most enthusiastic Albanian in America today. But Nisim’s older brother, he doesn’t know anything about the Albanian country. No wonder.

The relationship with this country, which created one of the most brutal, miserable and humiliating dictatorships in Europe, became a difficult thing for all of us who lived there. And their relationship with the country has stalled in the last installment of compensation for the persecution of their father, who was taken away from them by life, like my uncle, when he served five years in political prison as a youth in the late forties. And his wife’s people in Vlora. That’s not all, for better or for worse.

“We were born in Albania, we grew up in Albania,” Nesimi tells me. “I consider myself Albanian.” Eight years ago, Geri Kureta, who runs a children’s toy business here, returned to Albania from Israel. He tells me that even within Israel; the discourse on Jewish identity – which, especially after the Holocaust, was linked to immigration to that country – has changed. “It is not necessary to be Jewish and live there,” he says. “You can be Jewish anywhere, as it happens.”

Elio Jakoeli, one of the children of two Jewish survivors of Auschwitz who came and settled in Tirana, has his own store in Brooklyn, but he tells me that business is not going as well as he would like. He remembers his generation in Tirana, born in 1953, with fondness. “There is no generation like that,” he says. “Honest, good people.” A typical Tirana, 24-carat, Elio. Sometimes the idea of returning and living here excites him.

Jakov Sollomoni, who has recently written several books on the Jewish experience in Albania, was among those who left with the four of them in 1991 and now lives in Beersheba, on the edge of the Negev desert in southern Israel. In style, the narration of his stories moves from one direction to another, like a conversational conversation, and uses expressions of the Albanian of one who has that language as his own. He learned some vernacular Greek from his family. He learned English and Russian on his own, and even brought a poem by Lermontov into Albanian. Now he is also understood in Hebrew. “But to write, I write in Albanian.”

“The new generation is different,” he tells me. The son and daughter-in-law observe kashrut, the strict dietary rules of religious Jews, and keep the Sabbath. “We don’t,” he says. “My wife often makes me Elbasani casserole.” There is no more anti-kosher dish. Rashela Sollaku, born Matathia, is one of the few Jews from Ioannina who did not move to Israel. A chemical engineer, she decided to stay in Albania to take care of her husband, who needs health care. “He is also Muslim by origin,” she says.

She is the granddaughter of Mateo Matathia, who took care of taking over her grandfather’s houses in Vlora, something that seemed impossible to her in 1997, when one of them burned down and a crook had scratched a Nazi cross on the walls—and that backwards, counterclockwise. “It’s too late to move,” she says, when I meet her in a café in the center of Lushnja. “I have my life here.” But one young man, a computer scientist who studied in Rome, is preparing to leave for Israel, in search of this part of his roots.

In the first week of October, two days after the year 5776 began for the Jews, I found Marko Batino, the son of that Pepo who had saved the accordion from the Albanian soldiers, when in 1946, and they expelled him and his whole family, in his shop in Ioannina. I also met his mother, Nineta. Pepo, who passed away a few years ago, stayed in the shop until he could afford it, and whenever an Albanian came to his door, he would start a conversation in Albanian!/ Memorie.al

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)