From Kabil Bushati

Memorie.al / It have become customary at every school event for the first teachers to be proudly called “commissioners of light.” This epithet has now earned the right of citizenship as a reminiscence of the dictatorial past. However, there is a great nonsense in this phrase dedicated to our teachers. So, we remember those who found these letters ready and forget those who brought us these cherished letters through sufferings and extreme deprivations. Precisely, we forget those teachers who, a century ago, brought us and “nurtured” these beloved letters in Shqipe. No one remembers those teachers who wrote the letters in Albanian during the time of the Ottoman Empire, at a time when the triangle of the hanged hung over their heads like a curse of centuries.

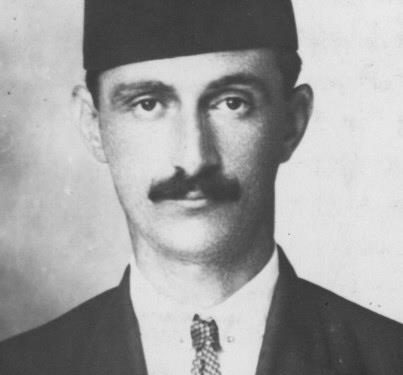

In this writing, I do not aim to confuse the reader, switching from one branch to another, but to speak briefly and accurately, with documents researched in the Central State Archive, about one of my ancestors who left a mark on the spread of education in Shkodra. Since my early childhood, I remember my older brother, Qazimi, telling me that my father took me by the hand and brought me to the graves of the “Dudas” mosque, and there in front stood a grave along with some other graves, where it was written “Molla Ahmet Bushati.”

These four or five graves were in the square in front of the mosque, for the most dignified people of the neighborhood. My father told me it was the grave of his grandfather. I begin from this grave, which no longer exists, along with the mosque, as the storm of “February 6, 1967,” flattened them all.

According to the documents we have managed to gather, Ahmet Bushati was born in Shkodra in 1833, the only child and heir of Hysen Bushati. He was born in the “Dudas” neighborhood, in the neighborhood of Dasho Shkreli, who lost his life in the Battle of Shpuza against the Montenegrins in 1835, becoming a hero in the defense of the Albanian lands. Shkodra still remembered the rule of the Bushatlies and held great respect for them. Nearly two years had passed since they fell from power, and the last Bushatli Vizier, Mustafa Pasha Bushatlija, had fled to Istanbul with his wife, children, and close relatives, leaving behind the complex of palaces in Kosmaç, which would later be taken by Drini, who had changed direction due to the earthquake.

Thus writes Nasuf Beg Dizdari in the magazine ‘Albania’ edited by Konica on July 15, 1898. According to the accounts of contemporaries, Ahmeti is noted as a student at the mekteb (traditional Islamic school) in the “Ndocej” neighborhood. This primary school was located close to his house. At the age of eight, he attended it along with other neighborhood friends for two consecutive years. Later, in Ahmet’s biography, it is recorded that as early as 1845, he began at a young age to learn Arabic and receive various theological lessons from the renowned teachers of the Medrese of the Pazar, an institution founded by Mehmet Pasha Plaku (Bushatli).

He later successfully completed the Medrese of the Pazar. Under the guidance of respected teachers like Salih efendi i Madh, Molla Ahmet Hadri, and Molla Sylo Fakja, as well as distinguished foreign educators stationed in educational institutions in Shkodra, a contingent of clerics was prepared, who later became prominent and honored themselves, the institution, and the country: Jusuf Tabaku, M. Ahmet Kalaja, Hasan Efendi Podgorica, Daut Efendi Boriçi, etc.

As it appears from the documents, my great-grandfather was born in the “Dudas” neighborhood around 1833. His house was near that of the Vorfaj family. I think it’s appropriate to clarify something regarding the name of the neighborhood, which to this day has been treated incorrectly. Let’s delve a little into the etymology of the word “Dudas.” Many professional scholars and entrenched amateur speculators trace the origin of this word to the name Dodë, softening the vowel to “u.” Many conformists, for various reasons, fanatically preserving and adapting to the prevailing circumstances of the time, have not opposed this inaccurate idea. While in my opinion, this word derives from the Turkish word “dud,” which means “mulberry,” a place with many mulberries, thus meaning Dudas. Such a word is meaningful because in “Dudas,” there was a forest with mulberries, which the citizens used the leaves of to raise silkworms. At that time, the city of Shkodra produced silk of poor quality.

His father, Hyseni, came to this neighborhood of Shkodra with his entire family around the years 1794-’95, having migrated from the “Tabake” neighborhood, near the Castle. With the fall of the Bushatlies, Hyseni was left alone in this world, as three of his brothers were killed in the last battles of Mustafa Pasha Bushatli in the battles of Tarabulluz, fighting for the honor of the Bushatlies. This neighborhood no longer exists as such today.

It was located at the foot of Rozafa Castle, on the right bank of the Drinaz (Drin) river. The name of this neighborhood before the Turkish invasion is unknown. With the arrival of the Ottomans, the neighborhoods around the castle took the names of benefactors, geographic position, or the profession that was most commonly practiced by the inhabitants of that neighborhood. Specifically, the name “Tabake” derives from the Turkish word for “leather tanners.”

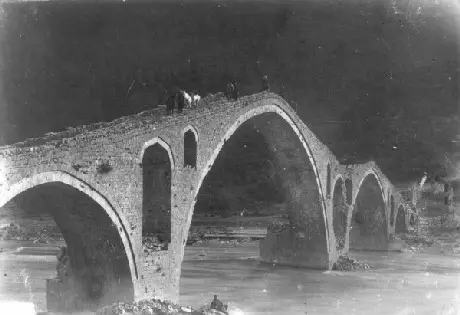

In this neighborhood, they primarily dealt with leather tanning, as it was located at the entrance to the city and welcomed the entire peasantry of the Lower Shkodra. This neighborhood had two main roads: one linked it to the Bahçallëk Bridge, while the other, which no longer exists, was the trade route that, after the Plumb Mosque, passed over the Kiri River, following the direction towards Vau i Dejës, Pukë, Prizren, etc. The “Tabake” neighborhood, during the period of the Bushatlies, was one of the more well-known neighborhoods and among the first in Shkodra. As early as 1846, the Drin began its deviation from its old riverbed, forming today’s Drinaz, together with the Kir River, and gradually filled Bunë with gravel.

Ahmet Bushati later successfully completed the Medrese of the Pazar. Under the guidance of respected teachers such as Salih efendi i Madh, Molla Ahmet Hadri, and Molla Sylo Fakja, as well as distinguished foreign teachers assigned to educational institutions in Shkodra, a contingent of clerics was prepared, who later affirmed themselves and became famous, honoring themselves, the institution, and the country: Jusuf Tabaku, M. Ahmet Kalaja, Hasan Efendi Podgorica, Daut Efendi Boriçi, etc.

As appears from the documents, my great-grandfather was born in the “Dudas” neighborhood around 1833. His house was near that of the Vorfaj family. I think it’s appropriate to clarify something regarding the name of the neighborhood, which to this day has been treated incorrectly. Let’s delve a little into the etymology of the word “Dudas.” Many professional scholars and entrenched amateur speculators trace the origin of this word to the name Dodë, softening the vowel to “u.” Many conformists, for various reasons, fanatically preserving and adapting to the prevailing circumstances of the time, have not opposed this inaccurate idea. While in my opinion, this word derives from the Turkish word “dud,” which means “mulberry,” a place with many mulberries, thus meaning Dudas. Such a word is meaningful because in “Dudas,” there was a forest of mulberries, which the citizens used the leaves of to raise silkworms. At that time, the city of Shkodra produced silk of poor quality.

His father, Hyseni, came to this neighborhood of Shkodra with his entire family around the years 1794-’95, having migrated from the “Tabake” neighborhood, near the Castle. With the fall of the Bushatlies, Hyseni was left alone in this world, as three of his brothers were killed in the last battles of Mustafa Pasha Bushatli in the battles of Tarabulluz, fighting for the honor of the Bushatlies. This neighborhood no longer exists as such today.

It was located at the foot of Rozafa Castle, on the right bank of the Drinaz (Drin) river. The name of this neighborhood before the Turkish invasion is unknown. With the arrival of the Ottomans, the neighborhoods around the castle took the names of benefactors, geographic position, or the profession that was most commonly practiced by the inhabitants of that neighborhood. Specifically, the name “Tabake” derives from the Turkish word for “leather tanners.”

In this neighborhood, they primarily dealt with leather tanning, as it was located at the entrance to the city and welcomed the entire peasantry of the Lower Shkodra. This neighborhood had two main roads: one linked it to the Bahçallëk Bridge, while the other, which no longer exists, was the trade route that passed through the Kiri River, following the direction towards Vau i Dejës, Pukë, Prizren, etc. The “Tabake” neighborhood, during the period of the Bushatlies, was one of the most well-known neighborhoods and among the first in Shkodra. As early as 1846, the Drin began its deviation from its old riverbed, forming today’s Drinaz, together with the Kir River, and gradually filled Bunë with gravel.

Among other things, the Valiu emphasizes for Daut Boriçi: “Since with the letter dated February 15, 1871, you inform us that starting from February 27 of the year 1871, as the teacher of the mekteb at Ana-liqeni (New Neighborhood), instead of the removed Abdullah Efendi, Ahmet Efendi Bushati has been appointed, against the monthly salary of the teacher, but until today the official registration of this order has not yet been carried out by the Governing Council of the Vilayet. From today, it is ordered to carry out this procedure, February 23, 1871. Ismail Haki, Vali and Commander of Shkodra.” (Taken from Daut Boriçi’s Diary, page 70, preserved in the Central State Archive).

The Muslim element of the city had mektebs as centers of primary education, where only one hoxha taught, who was paid by the students, with the exception of some teachers who were paid by the state. Here, young children and youths aged up to 13-14 years learned. These mektebs were known by the names of the hoxhas who taught and were located in the Old Bazaar as well as in the city. Well-known mektebs in the Pazar were: the Mekteb of Molla Ferhat (1830), of Mulla Halil Boriçi, of Mulla Mustafa, of Mulla Kamberi, of Mulla Abdyl, of Mulla Abdullah the Little, of Mulla Hysein Shazi, of Mulla Sylo, and of Mulla Jakupi. After completing the mekteb for a period of four to five years, some of the boys continued their education in the medrese, while others became apprentices with craftsmen or traders.

As the city began to advance with regular primary schools, the mektebs of the Pazar lost their importance, and from 1910 onwards, they began to close one after the other. A series of mektebs of this kind operated within the city, with the most mentioned for discipline and attendance being that of Molla Medo (1892) in the city center. It gathered about 500 children aged 6-14.

Since the last quarter of the 19th century, 11 mektebs were opened in various neighborhoods of the city. Among this successful group of education enthusiasts is also Molla Ahmed Efendi Bushati. It is no coincidence that two years later, Daut Boriçi, as the director of education for the Shkodra vilayet, sends a letter to the Vali of Shkodra, requesting that Ahmet Efendi Bushati open for the first time the mekteb in the “Dergut” neighborhood.

Ismail Haki, Vali and Commander of Shkodra:

“Following the request from the residents of the ‘Dergut’ neighborhood, through an official letter, I have clarified that there are no additional funds for the education budget and this situation does not constitute an urgent matter, regarding the allocation of the funds requested (by the people), as well as in other similar cases, but especially regarding the salary of 195 groshë for the teacher of the mekteb, which is given to the imam of that neighborhood, Ahmet Efendi Bushati, if it is possible to be covered by the municipal fund, and the state leaders have granted the requested permission regarding this matter, and the office of the municipality, through an official letter (bujrulldi), has ordered to act in accordance with the received order, according to which the specified salary has been included in the municipal budget starting from March of the year 1874. Therefore, through this letter, we remind the Governing Council of the Vilayet that we aim to inaugurate the opening of the aforementioned mekteb, which is planned to be established with the financial assistance of the residents of the neighborhood, on March 4, 1873.” (Taken from Daut Boriçi’s diary in Ottoman Turkish, page 121, preserved in the Central State Archive).

The opening of the mekteb in the “Dërgut” neighborhood by Ahmet Efendi Bushati was an important event for the entire community. Everywhere in the neighborhood, it was a true celebration. On that day, all the residents of the neighborhood, with children and families, gathered to joyfully inaugurate their mekteb. He did all of this for the sake of God, sacrificing his precious time, not considering the exhaustion and hardships, often facing even heavy expenses for his wallet, just to achieve success.

His dedication and devotion, accompanied by his will and relentless efforts, ensured that knowledge and skills in leading religious activities in the neighborhood where he served, at the mosque of “Dërgut,” were firmly connected to the life of the people, to their concerns and problems. These daily social problems, at certain times, took on a pronounced patriotic and political character; thus, Ahmet Efendi, although a devoted cleric, became a spiritual leader in many fields of social activity, mainly in family life that concerned the patriotic education of the children in Dërgut.

In 1857, he was an active member of the Dega (Branch) of the League of Prizren for Shkodra, a branch led by Daut Efendi Boriçi. Ahmet was part of the clerico-political-patriotic elite of Shkodra, which, on June 10, 1878, even before the proper establishment of the League of Prizren, positioned it directly and quickly declared its support for the League of Prizren. On this date, it was announced that Shkodra would join the League and would send its delegates, who set out late due to the situation created at the border with Montenegro. His political activity stood out everywhere.

After several years of intensive work, Ahmeti was transferred as imam and mekteb teacher to the mosque in the “Dudas” neighborhood, where he worked uninterrupted until the end of his life. He left behind only one son, Alushi, who married Nurija. Alushi had two sons, Ahmeti (Meti) and Rizai, who filled the house with boys and girls: Qazimi, Qamilin, Kabilin, Fatmirin, Fitnetin, and Driten. The eldest son, following the Shkodran tradition, bore the name of his grandfather. In “Dudas,” we were neighbors with the esteemed family of Alo Vorfa. It should be noted that Ahmet’s nephew, who is my father, participated, along with the youth of the neighborhood, in the Battle of Koplik in 1920, but I will present this in more detail in the family history I am writing.

After a successful career that any teacher and any religious servant would envy, in the middle of 1911, Molla Ahmet Efendi Bushati closed his eyes forever and departed from this life. His funeral was magnificent, with wide participation from all of Shkodra. He was buried in front of the “Dudas” mosque, alongside the distinguished people of this neighborhood. This grave would later be destroyed by the dictator along with the mosque in 1967, when Albania proclaimed itself “the world’s only atheist state.” Memorie.al