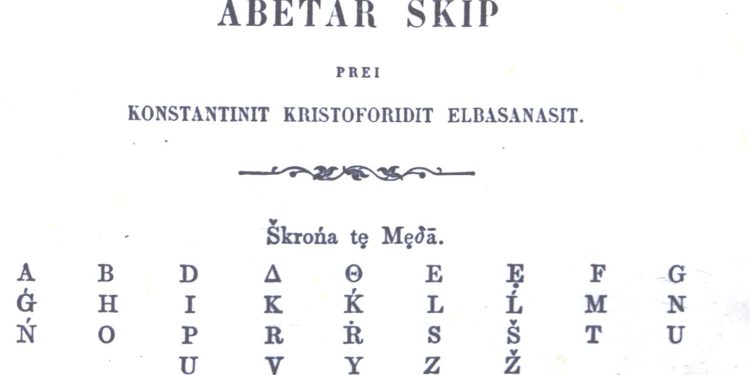

Memorie.al /At the time, the missionaries of the British and Foreign Bible Society didn’t know that, along with their work, they were doing a service to Albanian history. Everything was documented in detail, even under strict supervision, as if it concerned a dangerous agent. Kostandin Kristoforidhi, the translator of the Bible into the Albanian language, the creator of a primer in Gheg, an Albanian grammar, and the “Dictionary of the Albanian Language,” is perhaps one of the rare figures of the National Renaissance whose life has been documented so thoroughly. The manuscripts from the Bible Society Archives in London have now reached our readers in the book “Kristoforidhi through Documentation,” prepared by Prof. Dr. Xhevat Lloshi. There are a total of 150 documents, primarily from the British archives, published here for the first time.

These documents date from 1857 to the beginning of the 20th century, with some additional documents found in the Albanian Archives. According to Professor Lloshi, the importance of publishing these documents is manifold. For the first time, the life of a National Renaissance figure is revealed in its full complexity. There are no generalizations. “For Kristoforidhi, even the last pennies he received have been documented,” says Prof. Lloshi.

And all this information from the documents sheds light on many aspects of Kristoforidhi’s life, not just as a patriot, translator, or linguist, but also as a man, with his good and bad sides. Because of the religious nature of his work, Kristoforidhi was viewed with some reservations by the past regime. However, the documents show that he was not a Christian believer, which in fact posed a great problem for the Bible Society where he was “recruited” in 1865, as the most worthy successor to Vangjel Meksi, the first translator of the New Testament into Albanian.

But the society could not sever ties with the translator because, according to its own leader, he was the only person who could perfectly accomplish the translation of the Bible. “I repeat what I have often written and what I have told you and Mr. Braithwaite here, that Mr. Kristoforidhi is without question the most capable man and I would say the only competent man for the work that needs to be done,” wrote Alexander Thomson, the Society’s representative, on March 18, 1873, to the Publications Committee in London.

Through Kristoforidhi, other figures of the National Renaissance are also revealed, as well as foreign Albanologists who were in contact with him, such as Johann Georg von Hahn and Gustav Meyer. The documents also bring to light a conflict between Kristoforidhi and Naim Frashëri. In a document from 1896, found in the Central Archives of the Albanian State, Naim Frashëri writes, among other things, to Vasil Tërpo: “Do not give money for Kristoforidhi’s dictionaries, because it is not true, we saw it ourselves.”

Lloshi presents a large number of documents that also shed light on the fate of the Albanian book in the 19th century—how they were printed, published, and distributed. Xhevat Lloshi explains that the documentation of every detail of Kostandin Kristoforidhi’s life in the archives of the “Bible Society” is related to a very simple fact. “‘The Bible Society’ had a book to sell, so it was interested not just in the translation, but also in its distribution and sale.”

It sent its “missionaries” throughout Albania to observe the situation in every city and to deal with “marketing” issues, as they are called today. Through the reports and dispatches of these envoys, the situation in Albania in the 19th century is presented, including the distribution of schools, the level of education, illiteracy, the population numbers, religious beliefs, and the performance of religious rituals. There is even an interesting case regarding the latter. In 1867 in Elbasan, masses were held in the Albanian language.

“When the service reached the point where a chapter from the New Testament is read, we saw the deacon take the book and begin to read. His voice was not distinct and he started to mumble, but now it became even worse, so that I could not catch a single word, although the people seemed attentive and interested. I quickly grew suspicious about this and thought the scriptures were being read in Albanian, and I saw that they were.

This was something extremely pleasing and showed a preference on the part of the clergy who supported the upliftment of the people. But we learned with sorrow that the Bishop was so much against this that when he was present in the church, it could never be done,” writes Thomson in 1867. Through the latter’s letters, the Society’s direct interest in the spread of the Tosk dialect is shown, so that their book could also find a place.

These documents also shed more light on the creation of the alphabet, on events and dates that, according to Lloshi, should be taken into account. “Documents have been published regarding this, however, historians have not taken them into account and no change has occurred in history. History cannot be made without documents,” says Lloshi, adding that history cannot remain “prey” to the names of historians or linguists.

“Kristoforidhi through Documentation” is divided into two parts. The first part contains 31 articles published over 30 years by Prof. Dr. Lloshi in various media outlets, while the other part contains documents extracted from the archives. The first part serves to explain the documents. This is because the researcher Xhevat Lloshi always tries to explain the facts through documentation.

The Research

Before the 1974 Plenum, when a breeze of liberalization had blown in Albania, it was proposed in the scientific institutes to conduct research in foreign archives. Possible places included France, Austria, and even Britain, although there was not much hope with the latter due to the relations up to that point. However, the request was made, and two years later, from the British side—who saw it as a step towards Albania’s opening—came the approval for two Albanian researchers, Xhevat Lloshi and Arben Puto, to go to England.

“Knowing the fact that Kostandin Kristoforidhi had worked for the ‘Bible Society,’ I insisted on working in the archives of this society. During World War II, the archives of the ‘Bible Society’ were bombed, so there was not much hope of finding something valuable; nevertheless, I set out in search of everything related to the Albanian language,” he recounts. This search did not go in vain, as Xhevat Lloshi brought back a very large number of documents.

From 1972 until today, he has continuously written and published the documents from his research. A part of them is published in “Kristoforidhi through Documentation.” Prof. Lloshi is preparing a second book with documents, not only about Kristoforidhi but also others. Documents from the years 1884 to 1944.

Berat in the 19th Century

Alexander Thomson to C.S. Jackson

October 15, 1867

“Like Mostar in Herzegovina, Berat occupies two sides of a narrow gorge and is at a point of strategic importance. The castle or upper city occupies the top of a hill some 300-400 feet high and has a strong wall with towers that hang over the abyss, beneath which flows the Berat River. The city of Berat lies on the right side of the river, partly below, but mostly above, where the castle hangs over the river.

Near this abyss, one of the main Orthodox churches has been built, and from this point, an old bridge has been constructed that connects the banks of the city with the ‘Gorica’ neighborhood. It has perhaps 12,000 inhabitants, half of whom are Orthodox. This is the northernmost line of the Tosk dialect of Albanian.

We found the inn we headed for full, but had no difficulty in finding an acceptable place in another one up in the Bazaar. As soon as we dismounted from our horses, we were warmly greeted by a small group of Spanish Jews, who were happy to see that I could speak their language, as well as two Italians, who supported themselves by making plaster figurines of Garibaldi, Napoleon, and prominent people of our days, as well as flowers, animals, etc.” / Memorie.al