By Dalip Greca

Part Two

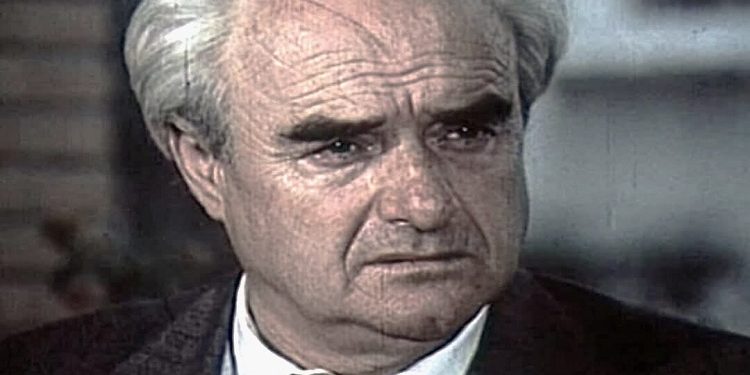

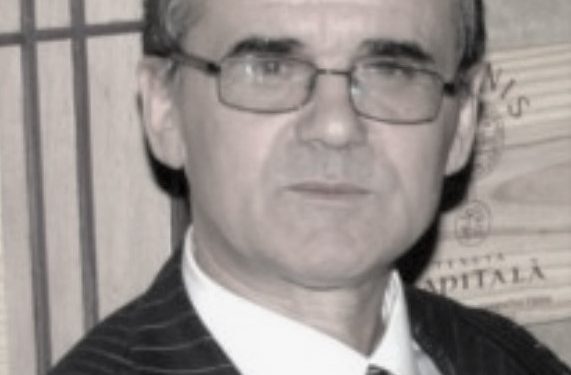

Memorie.al / Zoi Shyti (Zois Shuttie), is an artist who has long stood out with his unique creative individuality and has left his mark in America and Europe, he has been welcomed in the capitals of world art; in Paris, London, San Francisco, Mexico, Washington, New York, Philadelphia, and then in Tirana. As an artist and as a man, he carries an interesting story; mysteriously saved from death, helped by fate in the ruins of World War II, when he was still a child; barely raised with hardships in the difficult post-war period, educated at the Artistic Lyceum of Tirana, where, completely against his inclinations and desires, he studied sculpture and not painting; appointed first as a painter in the Tirana Crafts, then as a painter and sculptor in the Border Directorate; he finds the moment and escapes to Greece.

Continued from the previous issue

The country of the Hellenes did not offer him hospitality; reserving him a hardship, because they did not want to believe that he had fled as an artist repressed by the lack of freedom. It took him a lot of effort to prove that he was not an agent of the State Security, as was suspected, but an artist who sought freedom of speech and artistic freedom. He came to the free country (USA), where his father had previously been and settled in the city where his father had lived, in Philadelphia. After the difficulties of the beginning, he managed to realize the dream he had carried with him since Albania; studying at a renowned art school in America. He enrolled in the “Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts”.

After graduating with honors from the University of Pennsylvania of the Fine Arts, he traveled to Paris and London to explore the magical world of art. It was at this time that he received an invitation to teach at the renowned Academy of Florence, the capital of the Renaissance. He taught sculpture for 6 months to a group of American artists, but was forced to abandon teaching for health reasons. He returned to Paris and from there to Philadelphia. In 1973, Zoin was a professor at the Free University in San Francisco, then lectured at the Instituto Ajende in Mexico. He exhibited there; he would later exhibit in Paris, where he received an honorary degree, and a few years later he would be honored there with the Silver and Gold Medals, in other exhibitions that would also open at the Grand Salon des Artists Française.

In 1978, he created a portrait of Skanderbeg, commissioned by the Skanderbeg Square commission, a portrait that he donated to the Paris municipality, as a sign of respect for what he did for the Albanian people. Precisely in 1982, Zoi returned to New York and then went to Washington, where he began working as a journalist at the Voice of America. Even though he was ill, with a definite diagnosis, he did not leave his studio in the Bronx. What path did Zoi’s life and artistic activity take later? What is his odyssey with the panels dedicated to Mother Teresa, which he has not been able to take to Tirana for 10 years? Let’s follow the interview.

– Mr. Shyti, despite having health problems, you are still surviving the unrealized pledge to send your cycle of works dedicated to Mother Teresa to Albania. Do you still have hope that one day, you will be in Albania together with the cycle?

Yes, of course I have hope. Without hope, nothing gets done. I do everything I do, day after day, for the sake of hope; that it will turn out well, that it will be seen favorably by others, that it will end up on the walls of some new collector, and so on, that a life without hope would be a meaningless and worthless life. I cannot solve my health issues, because they are a matter of medicine and a matter of fate. I only obey my fate and hope that “better days will come after this”. Hope heals. This is how I exercise my artistic and creative work, despite unforeseen difficulties.

Under what circumstances did the multi-panel cycle for Mother Teresa come into being?

When I was working as a correspondent and news anchor for the Voice of America and when, for the first time in my life, I bought my own house in Washington, in 1985, Mr. Albert Akshia from Rome asked me on the phone to write something about Mother Teresa, for the international competition organized by Dom Lush Gjergji in Ferizaj, Kosovo. I promised him and kept my word. I sent him the poem “Mother of Pain”, a spur-of-the-moment improvisation, and a month later he called me to inform me that my poem had won first place in that competition, and he recited it on the phone. In the end, he asked me to bring those images to painting, with the same force of beauty. I promised him again and made some studies, some small sketches, which I liked.

It was not his call that put me in front of this further pictorial mission; it was fate itself that influenced the further direction of my life. I decided to quit my job, sold my house, and moved to South Miami Beach, Florida, where the tropical climate exposed me to the naked life of the weaknesses of alcoholics, drug addicts, thieves, and other people with vices, a phenomenon that gave me abundant material for my project.

That happened 19 years ago. Now that the project is finished, its place is no longer in my studio, because it belongs to the public, to enjoy and judge it, according to its own level. The issue now that the entire project is finished is very easy and solvable, because now everything remains in the transportation and insurance for the exhibition. As they say in English: “When there is a will, there is a way!”. (If there is a will, there is also a solution).

How was the cycle about Mother Teresa received? Were there any comments at the beginning of its realization?

I will begin my answer with a quote: “Your idea of a permanent altar dedicated to a Living Saint,” wrote the Jungian philosopher-analyst, Dr. Roger J. Radloff, on April 30, 1987, when he visited with the mayor of the city the first six panels of the cycle at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Coral Gables, Florida, “is an excellent idea and at the same time stands in opposition to the conditional love so often moralized in our day, in the name of the dead and of the inconceivable causes of the past.”

Where and when were the panels, at the center of which was Mother Teresa, exhibited, and what reception did the public have for them?

This cycle of large paintings was first exhibited in its entirety in 1991, in the Rotunda of the Palace of Congresses, organized by Congressman Tom Lantos and Congressman John Porter, of the Human Rights Commission of the United States Congress. Thus, they gave this issue the opportunity to publicly recognize Mother Teresa as an Albanian daughter, thanks to the slogans that I placed at the entrance to the exhibition. But I say with regret that none of the Albanians in Washington took the trouble to pay her a visit, with the exception of the little dancers of New Jersey and the crowds of American students and visitors, who filled the halls with their curiosity. Even those selected Albanians of the Diaspora who came to Washington to talk with the State Department to open their first businesses in Albania at a time of social turmoil that shook the foundations of the red bastion, did not even bother to return to find out what this artist has done to us with these images!

How do you explain the indifference of the Albanians?

I do not comment, I only bring facts. I would like to add that for the Flag Day celebration at the New York Hilton that year, they also invited me to bring the exhibition panels to the Albanian public. When I arrived in the hallway with the large panels, the organizers did not even glance at the works. After the event, everyone disappeared and I was forced to stay that night with them in the hotel, until the next day a means was found to take them to my studio.

No one came forward either for the bill or for my concern. So, this unrealized pledge, as you call it, to exhibit the work dedicated to Mother Teresa in Albania, is more of a pledge of other interested parties, who have expressed the desire to bring this work to the Albanian public, but who, to date, have done nothing to realize it. I am filled with empty promises, but I am still hopeful!

You once packed the paintings to Albania, and even sent them to the airport, why didn’t they arrive in Albania?

Ah, yes, past history. It was ‘Arbëria Airlines’, the first airline company offering direct tourist flights to Albania, that took over in 1993, sending this cycle with the cargo of its plane. But the ‘Arbëria’ craze, came to us like a wildfire, it ignited quickly, spread quickly and died down quickly. At that time, I remained in the ‘Arbëria’ offices, communicating by phone, fax and letter with the Minister of Culture, with our representation at the UN and with the first Albanian ambassador in Washington, so that they would be patient.

‘Arbëria’ even made invitations to the opening of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Arts under the name of Dr. Sali Berisha, on the occasion of the visit of His Holiness, Pope John Paul II, to Albania. But after paying ‘Arbëria’ for that trip, I packed up my things and took them to the airport. The plane never took off from the runway and the money was never returned. Only the bitter event and the owner’s shame remained in my memory.

When did you visit Albania for the first time, after your escape?

In early 1992, the director of the National Gallery of Arts, Mr. Xenofon Dilo, called me and assured me that it was not at all dangerous for me to return to free Democratic Albania, with a few small works, for an exhibition in my homeland. “We, your friends, will wait, together with your mother, whose heart is crying for her son who has been missing for 28 years. Come on… let’s go”!

It was the time when Ramiz Alia was in power and I was known as the fugitive of the Ministry of Interior. But the call of the mother was greater than the fear that something might happen to me. I went and we missed her. The exhibition with 175 small works on paper was welcomed by all those who visited it. Two years later, Prof. Ylli Popa and I had an audience with President Sali Berisha, at Villa no. 4, on the issue of bringing the exhibition of Mother Teresa to Albania.

Once again, this exhibition became a media issue: “When will the exhibition on Mother Teresa come to Albania”? wrote RD in 1994; “A seagull landed again on the shore…”, wrote the newspaper ‘Republika’ in 1992, and “An Artist Returns Home with a Mother Teresa Art Show” wrote Isuf Hajrizi of ‘Illyrië’ in 1992. But no one has yet been able to answer these media calls.

Have the paintings of the cycle dedicated to the humanist Mother Teresa been lucky enough to be exhibited in any other exhibition?

In 1998, the main works of this monumental cycle remained hanging on the walls of my apartment in Brooklyn, where from time to time a few friends and teams of Albanian correspondents from both sides of the Atlantic came for interviews. We also had the Diaspora television program, then kept alive by the Osmani brothers. It was at that time that I was struggling with the disease, but it put me down, with my shoulders on the ground.

An American friend of mine brought me with him one day and the curator of the Hargate museum. She was amazed by what she saw, even though she had visited many artists’ studios before me, but she could not imagine why this art project was about the extraordinary humanitarian figure, the most famous in the world at that time.

She chose those works that spoke a common language with her, since the exhibition hall there, she said, did not have enough space for all the works that made up the project. The works were transported in a special vehicle insured for more than a million dollars, in case of any unexpected events. That entire week after the exhibition opened, I, their guest, had been scheduled to give talks and paid lectures to art students and professors on the subject of inspiration and execution of such a self-commission, since it seemed incredible to them that this cycle dedicated to human misery, through the figure of the Albanian Nobel Prize winner, had been made with the artist’s own funds.

I explained that it was my need to discover my will that prompted me to spend over 65 thousand dollars to fulfill this order born as a capricious need of the artist himself. But it so happened that after my return to New York, from that exhibition, I was urgently hospitalized for two surgical interventions. But why complain, I have hopes that I will be even better when I leave the next operating room that will take place in the first week of September. You, see?!… That is why there must be hope!

The odyssey of your artistic “Testament” began in the early years of democracy, when the Democratic Party was in power and President Berisha, who at that time had issued orders to ministries to support your initiative, where did the problem get stuck?

The project began precisely in 1986 and after that, “stone upon stone, a wall is built,” says the popular proverb. I had it completed in 1991, when it was exhibited at the US Capitol in Washington. But in the spirit of Democracy in Albania, I also painted a group of Albanian democratic leaders, such as Dr. Sali Berisha and Dr. Ibrahim Rugova, in the main painting with portraits of freedom-loving leaders gathered around Mother Teresa, Pope John Paul II, the Dalai Lama and Cardinal O’Conner.

Where did the issue get stuck?!… is your question. In the above answer, I almost clearly explained the major obstacles of empty promises on the Albanian side, since we are not educated to see works of art, especially figurative arts, with eyes developed from an aesthetic, artistic or cultural investment point of view. Unlike music and sports, which satisfy us instantly, figurative arts experience centuries of history of identity and national sensitivity.

Did you make other efforts to bring the cycle to Albania?

In 1994, I went back to Albania, as my mother was already on her deathbed. I stayed with her for the whole month. Doctor Ylli Popa informed me that President Sali Berisha had invited us to visit his villa, to discuss what could be done to bring the project on Mother Teresa to Albania. I opened all the illustrations and reproductions, to which he said:

“Why didn’t you inform me before the visit of His Holiness, Pope John Paul II, who was here for a visit?” I replied: “Why didn’t you invite me before the Pope’s visit, when the Ministry of Culture was contacting me by phone and fax, three years ago”? After a silence by the roaring fireplace, his car accompanied us to our apartments.

You have received an official invitation in May 2005, from the director of the Art Gallery in Tirana, Abaz Hado, and another invitation in July 2005, from the director of the Museum, Mr. Moikom Zeqo, do they constitute hope for concretizing your effort?

I hope that the Democratic government of Dr. Berisha, with the experiences of the first leadership period also in the branches of art and national culture, may now be better able to bring this traveling exhibition to the above-mentioned countries. But there must be patience and a willing pace. Last December I went to Tirana again and this time I discussed this issue with the two directors of the country’s highest institutions: with the director of the National Art Gallery, Mr. Abaz Hado, and with the director of the Historical Museum, Mr. Moikom Zeqo.

Both of them approved sending two exhibitions there: the first as a Retrospective exhibition, of my entire artistic life for the National Gallery of Arts, on November 15-30; and the other exhibition, which would open with the works of the cycle on Mother Teresa at the Historical Museum, December 1-15 of this year. But it took them six or seven months to send me the official invitations to confirm whether these promises would be fulfilled, or not?! I have by now an understanding of the phenomenon of not being correct, among our people, even though we are very meticulous in our relations with foreigners.

For this reason, the issue now hangs in the air, truly an unrealized hostage. I regret that all my attempts so far, to take this project to Albania and neighboring countries, have failed. However, to send a humanitarian work dedicated to Mother Teresa with the invitation of those institutions, sponsors must be found. And I cannot find sponsors, just as a diaspora organization can find them with great ease. That is why I say that this pledge is an Albanian pledge, because I myself, my conscientious duty to the nation, have fulfilled it with my talent, work, time and expenses. The rest now depends on the conscience of others.

Have you made any efforts to address the Albanian diaspora to sponsor the transportation of the paintings? Have you addressed specific businessmen, or any Albanian-American association?

In order to address the Diaspora for such assistance, the Diaspora must first be made aware of the existence of this artistic spectacle, which involves the transportation and appropriate insurance of these works of art, from the moment they leave my studio until they arrive in Tirana, and from there, if the Ministry of Culture intervenes with the sister Ministries of neighboring countries, they can be sent to the capitals of the Albanian lands, and end up in Rome.

I hope that the Newspaper ‘ILLYRIA’, which has all the contacts with successful Albanian businessmen, in every corner of the United States, can make an appeal to them in its name, to restore the beautiful Albanian values in times of unrest, while not letting the Albanian name become known only through negative comments in the foreign media. It must be known that if we do not show our values, who will pour water on the fire for us? Even the media in Tirana can sensitize the public.

After such an announcement, I will be ready to go to those centers and illustrate the joint meetings with video presentations and other materials. But this should be organized by others with their requests. Also, requests should be addressed to private or state American entities by Gazeta Illyria, which is the only press organ that represents the Albanian voice in the free world, or by other individuals.

What new things can we expect in your artistic projects?

I am now dealing with a large framework on the recent genocide in Kosovo, which is still undergoing new excavations, where the extermination of man by man became the greatest physical and spiritual disfigurement of man, by the authors of the barbarities of extermination. I cannot predict what next step I will take later. I live from day to day. The future does not belong to me. It is only hope that keeps me alive in my world of art with literature and classical music. The rest is beyond the sphere of my will.

In which exhibitions has Mother Teresa and Zoi Shhytit toured in America and Europe and how was its transportation carried out?

We have explained the historical trajectory of all the countries where this project has been exhibited above. But the prices here in the USA, for the transportation and insurance of works of art, are higher than those in Europe. When it comes to traveling exhibitions, if two or more different institutions pay the expenses, the payments are halved. But public relations people have the upper hand here in terms of raising funds for that purpose. If an art gallery or museum requests an exchange of exhibits from one center to another, the exhibits move easily, and the expenses are shared.

In these cases, such institutions have large donors around them who keep the entire cultural and arts center open to the art-loving public. When the curator of the Hargate Art Center in Concord, New Hampshire, came to my studio and selected the works to be exhibited in their hall, she sent the museum’s vehicles with insurance coverage of over a million dollars. This made the driver and the packaging and loading experts be very careful about maintaining the works from the moment they left my studio until the time they returned. Memorie.al