From Blerina Goce

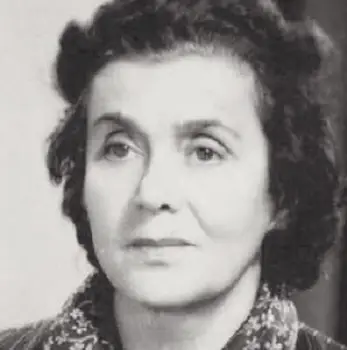

Memorie.al / Portrait of the artist Gjyzepina Kosturi in a confession by her son and those who knew her closely. The sister-in-law of Drita Kosturi, the fiancee of Qemal Stafa, persecuted by the communist regime, would have to bear the burden of being the head of the family, with an unemployed husband and a son imprisoned for agitation and propaganda. But paradoxically, she would remain a soloist at the Opera Theater. Zhani Ciko talks about getting to know her and why they tolerated her presence on stage. Her photos look like they came out of the Cinecitta archives. Beautiful, stylishly dressed, with an unequivocal elegance, Gjyzepina Kosturi, was one of those women, that everyone could not help turning their heads when she passed by on the street. Who with worship, who with laughter. She remained like that until the end, even when being “bourgeois” was considered a “damka”.

As the wife of Rexhai Kosturi, Drita Kosturi’s brother, Gjyzja, as Gjyzepina Kosturin was often called by friends, would be forced to be both the wife and the man of the house. With an unemployed husband, due to the limitations and obstacles of the system, with a son who experienced the suffering of prisons, Gjyzepina Kosturi, would be what her husband would describe her as; “my husband” or, in other words, the man of the house. However, whoever has known Gjyzepina and heard her voice has in mind a very delicate and special woman.

With a rare charm for the time, Gjyzepina Kosturi was among the few lyrical singers of Albanian opera, who really brought her the original spirit. Educated at the conservatory “Santa Cecilia” in Rome, there was no way it could be otherwise, since Gjyzepina was the daughter of a family with tradition from Shkodra. The daughter of Gjokë Mislocë and Paolina Kodheli (Marubi), she was the granddaughter of the famous Albanian photographer, Kel Marubi (Kodheli).

Through and beyond significant facts, the artist Zhani Ciko, one of the people who knew Gjyzepina Kosturi closely, draws an artistic and human portrait of the talented singer. A family friend with her, also because of her father, Mihal Ciko, he remembers that: “The grandmother grew up with special care and sensibility in the field of music and in her person, stood out at every moment and everywhere, in the family, in the social environment, etc. This sensibility was crowned with a kindness that emanated from Gjyzepina’s eyes and her entire being.

Meanwhile, Gjyzepina got in touch with Rexhai Kosturi, an intellectual of the 30s-40s from the prominent Kosturi family, very important in Tirana. Drita Kosturi, one of the women in the vanguard of political and cultural developments, was his sister. Rexhaiu was a man formed in many directions. Whenever the occasion arose, even though I was a child, in those family settings where conversations took place, he always showed an encyclopedic competence. He knew many things, among the most special, he knew many foreign languages. Suffice it to mention that he was the only translator from Russian of the opera “Rusalka” when it began to be staged at the Opera House. I remember, when we gathered at our house, together with me, Rexhaiu translated it, while my father adapted the vocal genre of the opera”, Ciko confesses.

Gjyzepina Kosturi took her own path, first at Radio Tirana as a singer, where she appeared in various shows. Later, in addition to the lessons at the Artistic High School, in 1951, with the opening of the Philharmonic, he became involved with it. “I have very fresh impressions of the way he worked, in what is today the experimental theater ‘Kujtim Spahivogli’.

In the small rooms on the first floor, were the rooms of the soloists, and when I went there, always with my father, I constantly heard the voices of singers rehearsing for concerts. I was impressed by the emotional, special voice of Gjyzepina Kosturi. He had an inalienable vocal color, which he used very skillfully in order to break down the content. “Gjyzepina, more than anyone else, got used to the character, which she embodied in arias or stage works,” Ciko confesses.

A nature drawn towards its spiritual world, according to Ciko, without the flattery that some of the artists of the time were forced to give to the regime of the time, Gjyzepina did not have an easy artistic path. But her talent led her to perform some of the most important operatic roles, also because they could not easily find a second one like her. Thus, Gjyzepina performed the role of the queen in the first opera, “Rusalka”, alongside Jorgjie Truja.

Then, she performed in the opera “Ivan Susan” and “Cavalleria Rusticana”. Mentioning the performance in this last opera, which according to Ciko “brought out the complexity of the character he played”. If he has to remember Gjyzepina beyond the stage, Zhani Ciko remembers her as; “a beautiful woman who dressed tastefully” and who “Cooked wonderfully”.

A 50-year-old “Butterfly”.

A completely different performance was her appearance in the opera “Madame Butterfly”, with the role of Cio Cio San. “Here, too, dressed as a Japanese girl, with that usual bowing and gesticulation of Asiatics, and especially of the Japanese, she brought a freshness to all her movements, which was quite different from that of the other characters, though she was at an advanced age, around 50”, recalls maestro Ciko.

“I still haven’t found the Albanian Tatja, exciting like Gjyzepina”?!

Conductor Ciko notes that; Gjyzepina performed very well the role of Tatjana in Tchaikovsky’s opera, “Eugene Onegin”. “It did not belong to the Russian school, or to what was constantly interpreted in our country. It was part of the western character in its formation and brought an unrepeatable ‘Tatjana’ to our stage. Years later, I decided to direct this page of ‘Eugjen Onjegin’ and I included it in a concert of mine, sung by other beautiful artists, but I absolutely never felt that emotion, when I was young, as a listener, I experienced amazed by the art of Gjyzepina Kosturi”.

How were they “forced” to give him “Traviata”?!

According to Ciko, the realism of the role of Violeta in “Traviata” was also impressive. “She raised Violeta at a somewhat older age, for the reason that always, especially in that ideologically restrained period, Gjyzepina, was not preferred by the circles for some reasons. And they were forced to give ‘Traviata’ to him, when no one else could do it.”

“It sounded wonderful…”!

At one point in her life, the famous artist had hearing problems. For this reason, she wore an earpiece when she sang. “Sometimes you could notice some intonation, involuntary movements of hers, due to the lack of orientation at these moments, but rightfully so,” notes master Ciko. “He was worried about this. One day I happened to be there, when my friend asked him, after the interpretation: How was I, did I have problems?! And he told her a phrase that stuck in my mind: Girl, even when you’re not exactly in the right tone, you do it wonderfully! It was as if he said to him: It sounds wonderful!

Gjyzepina was important for her parts. She kept her voice fresh until old age. I remember one concert, one of the last, when over 70 years old; she sang on our stage her repertoire of arias, which was very wide. It amazed you with its potency, because it believed in the soul, emotionality, realism of the figure. For him, the stage figure and the vocal one were one. It is truly one of the most important names of our operatic music, which has greatly inspired young artists, who have heard and experienced its emotions”.

Volfang Kosturi: “Mother saved us from exile, as we were labeled as ‘bourgeois'”!

“If we didn’t have our mother, we would all have been interned”, says the son of the famous soprano, Gjyzepina Kosturi, among others. The grandson of Drita and Skënder Kosturi, Wolfang Kosturi, who has been living in Italy for years, has a lot to tell when it comes to his family, and moreover, to his mother. He fanatically preserves every memory of his mother and in this conversation about her, he emphasizes that the difficulties of a life “under persecution” would not soften the sweetness and sensitivity of the artist Gjyzepina Kosturi.

Mr. Kosturi, what can you tell us about your mother?

The mother carried all the weight of the family. Thanks to mom, we survived. What he did in those years was only housework. She was a beautiful and hardworking woman. I must say that; if we didn’t have the mother, we would have all been exiled. She has kept us, from the political side.

Why did this burden fall on your mother, what about your father?

My father was the director of Tourism. Then communism was established, which he never accepted, never asked for a job, and became a slave. He did private translations and drew. There were also old friends, with whom he had studied abroad, such as: Ali Cungu, Suad Asllani, Emin Toro, etc., who came to us and played bridge. So, bridge was played in our family. Until then, employees of the State Security came to him and told him that he should not associate with them. Since then, for six years, he never left the house. Until he died on November 27, 1968, at the age of 62.

Why did your family come across as “bourgeois”?

Yes, true. We were classified as a bourgeois family, even though my father had a martyred brother, Skënder Kosturin. I remember that our friendship was never broken. I underline the fact that it is not true that my mother was Italian. She had gone to school in Italy, and then the Conservatory. But to her credit, she didn’t change her style. I remember that he always came out, with a hat and fur. When I was 16-17 years old, they called me “Italian m…”! The only “Italian” thing about us was that we had an aunt married in Italy, who sometimes sent us gifts or clothes.

Our misfortune was that we had the house in the area of the former “Block”. My mother, when she went shopping with a sun hat (in those years it was not common to wear a sun hat) said: “how beautiful the tomatoes are”! The old women of the neighborhood mocked him and said with disdain: “Wow this”! “First you see it with your eyes and then your mouth tastes it”, my mother replied. In the family, we knew Italian, but also Turkish.

So much so that for this reason, in the 20’s, they called us genies. Dad spoke six foreign languages and was a fan of Napoleon. In the family, we had our “old” way of life, and raising your voice was not discussed. We were educated. For these we were qualified, observed by the system. But the mother took care of us, three brothers and the husband. Her moral side and stubbornness kept us.

What do you mean when you mention her “stubbornness”?

I remember that, when it was her 70th birthday and she was about to go on stage, they told her: “Don’t go out in a long dress”! She was so convinced of the things she wanted that she refused: “If I don’t go out in a long dress, I don’t want the concert. How can I, 70 years old, go out in a short dress to a classical concert?! This issue went all the way to the Party Committee and it took the intervention of Rita Markos to allow her to go on stage in a long dress. It should be noted that she was from Shkodra, the granddaughter of Kel Marubi, who was her uncle and Toni Harapin, and she had a son.

You are the grandson of Drita Kosturi. What did your parents say at home about your aunt and how do you remember her?

Drita was an idealist. He joined communism as an ideal. From all these events, at home, mother kept the photograph with Drita. The father had declared that; this whole war wasn’t real, it was comedy. But he has never spoken about Drita, who made a mistake.

It was known about the aunt’s work, that she should not come and, if she did, it should happen secretly. But they never talked about what they were talking about. I went once, when I was young, to meet him in exile. She didn’t speak. When my aunt came to me, in Italy, in 1992, she was terrorized and did not believe that she was free. He didn’t speak. He only said: I was an idealist and this idealism led me here!

In your family, you also had an arrested person, your brother. Was this arrest related to Drita Kosturi?

Yes, they arrested my brother, Valter. It was the time when the class war became very strong and in 1976, they put him in prison for agitation and propaganda. Valteri was involved in motorcycle racing and was charming. They found the culprit, to put him in prison. He was released from prison in 1981. But the mother died of poisoning, four years later. They never invited him to parties; they didn’t bring him invitations and things like that.

In the memories of friends

Even though they were targeted by the system, the Kostur family was never closed to their friends. Now that neither the owners of the house nor many of the friends are living anymore, only the memories are left behind.

Amik Kasoruho: Rexhai Kosturi, dignified until the end

Rexhai Kosturi, was and remained until the last moments consistent with his thoughts and way of life. He didn’t reach out to anyone, not at all, because he didn’t need to, but because he respected himself. He didn’t beg anything from anyone, not because he didn’t lack many things, but because what he thought was the most important thing for a person, dignity, he kept intact and didn’t expect it from others. He was not a hero, but simply a dignified man. And to be like that, when heads were chopped off all around, because dignity was called “connection with the past”, “rotten bourgeois pride” or “reaction” to the government was not a small thing. On the contrary.

Mark Shkreli: Why did we like Kostur’s house?!

The door of that small apartment was “always open”, not only for us young people (friends of the boys), but for all those kind friends of the family, who happily frequented that house, always finding simplicity, generosity. Where in the “intellectual majesty”, only dignity and openness could be seen, where even a single piece of bread was sweet, where the mess (natural in the boys’ rooms), had more warmth than any other, and we went out, for to leave the “bridge players” alone. I remember how many artists and intellectuals I met there, many, many valuable people who frequented that environment, with an admiration and respect for both Gjyza and Rexhai. Memorie.al