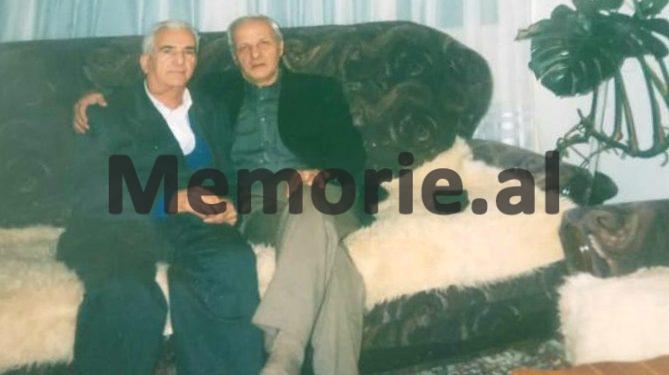

Esat Myftari

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Esat Myftari, originally from Peja, who was in high school benches when he was a member of a group of young boys who opposed the official Belgrade policy against the discriminatory policy against the Albanian population living in He started working as a journalist at “Rilindja” in Prishtina, from where he was proposed as a correspondent of the TANJUG Agency, but he refused and in 1963 he was forced to flee and come to Albania, with the aim of seeking help and support. from the mother country, for the clandestine organization of the “Boys of Peja”. Numerous vicissitudes in the mother country and continuous pursuit of the State Security since the time of studies in Tirana and the period when he served as an educator in the town of Shengjin and the villages of the Coast of Matë, where he was arrested in 1975, after he had officially requested repatriation to his homeland Kosovo, sentencing him to ten years in prison on charges of “agitation and prop agenda ”, which he suffered in the Spaç camp. The whole painful story of the journalist, publicist, researcher, translator, MP and diplomat, Esat Myftari, is described with literary mastery in his book, “Your death, my life” an autobiographical novel that has just come out from the Publishing House “Lena Graphic Desing” of Prishtina, and with the permission of the author, will be published in parts by Memorie.al

The unknown story of journalist, publicist and writer Esat Myftari

Esat Myftari was born on June 16, 1940, in the city of Peja in Kosovo, where his family originated from. He completed his first elementary school education, 7-year-old and high school, in his hometown, completing them in 1959. Also, in 1959, Esat, a 19-year-old boy, began his studies at the Faculty of Law of the University of Belgrade. A lover of history and literature, he started writing at a young age when he was in the 7-year school benches and in the faculty period, he became a member of the Literary Club “Përpjekja” based in the Student City of “New Belgrade” , where he affirms himself quickly and from time to time, writes poems and critical literary views, but due to their content, does not send them for publication. In 1961, after successfully passing the relevant competition, Esat started working as a journalist in the daily of the province of Kosovo, “Rilindja”, where he is assigned to cover the chronicle of the city of Pristina and the Kosovo Trade Unions. In the same year, he was offered a qualification scholarship at the Yugoslav TANJUG Agency, with the prospect of becoming a correspondent outside the then Yugoslavia. But his joy at the qualifying scholarship that was destined to send him abroad was quickly dashed, as the specialization offered to him was conditional on his membership in the Communist League of Serbia, which 20-year-old Esat refused. categorically.

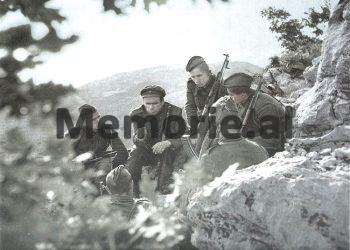

Meanwhile, in 1963, he participated in a group of young men who disagreed and were against the policy pursued by official Belgrade towards the Kosovo Albanians and wherever they were in their lands under Yugoslavia, and on behalf of the “Peja clandestine group”. , as their representative, crosses the border illegally and comes to Albania. Esat’s goal as a representative of the “Illegal group of boys of Peja”, was to establish contacts with the Albanian state and to seek various support and assistance for the well-functioning of that group of young boys, which aimed to resist the discriminatory policy of official Belgrade to the Albanian population in Yugoslavia.

In 1974, some members of this group were arrested by the official authorities of the Yugoslav Ministry of Internal Affairs, accused of participating in the events of 1964, when the Albanian national flags were unfurled in the main cities of Kosovo and when they were taken strict police and judicial measures against them. The main motto of this mass movement, which was the first of its kind in post-war Kosovo, was the unification of Albanian lands with their “mother” state, Albania.

Meanwhile, Esati, who was in Albania, as well as some of his Kosovar emigrant compatriots in Albania, gained a right to study and in 1965, he began his studies at the Faculty of Natural Sciences in Tirana, in the “Bio-Chemistry” branch. After the third year of studies, disappointed by the official policy of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and the treatment of Kosovar emigrants in Albania, who upon their arrival in their homeland, it seemed that “from the rain they had heavy hail”, interrupts his studies and requests repatriation!

Of course, this was not approved by official Tirana and in 1969, Esat started working as a teacher in the 8-year school in the town of Shengjin, in the district of Lezha, where he worked until 1974, from where he was transferred to the village of Tale. of the Mata Coast, where he also worked diligently. As during his entire period of work and residence in the district of Lezha, Esat was regularly monitored by all means by the State Security organs, even in the school where it was said that he had been sent on purpose, as they feared an escape from his opportunity to go to Yugoslavia from Shengjin, he is arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison, accused of “agitation and propaganda against the popular power”!

After serving his full sentence while serving his sentence in the Spaç camp, etc. (not benefiting from a single day of reduced sentence), Esat was released from political prison in 1985 and returned to the district of Lezha where he had worked and lived before the sentence and in 1986 , starts working as a worker in the Paper Factory in Lezha. That same year he started a family and then two sons were born.

In 1990, at the beginning of pluralism, Esat took an active part in the popular movements for the overthrow of the communist dictatorship in Albania and with the establishment of the branch of the Democratic Party for the district of Lezha, at the beginning of 1991, for his past and contribution. great at the beginning of those popular protests, he is elected secretary of that branch.

Also as a result of that contribution, in the first pluralist elections of March 22, 1991, Esat was elected a member of the Democratic Party in the People’s Assembly, representing the voters of the Mata Coast, where he had worked as a teacher until the day of his arrest in 1975.

A year later, in the autumn of 1992, he was appointed Director of the Diaspora Directorate at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Albania, headed by the Minister, Alfred Serreqi. In that position, Esat worked diligently until 2000, when he was appointed diplomat at the Albanian Embassy in Riyadh, where he remained until his retirement.

Since that time, Esat has been devoted to his passion, writing, studies and translations and since 2011, he has started publishing several books, which have been welcomed by critics and readers, also because of their subject matter, as well as the variant of Gegërisht that he wrote them, which is very rare in Albanian publications of the mother country!

The first book published by Esat Myftari is “Emrush Myftari” (monograph), and after him come: “Kosovo and Enver Hoxha” (study), “Political profile of Esat Mekuli” (monograph), and “Your death, life ime ”, which is an autobiographical novel, where he has masterfully and chronologically described most of his life, from family and life in Kosovo as a high school student, escape to Albania, the many vicissitudes of surveys of State Security prosecution, arrest, investigation, trial and deportation to Spaç prison.

All the events and everything described in the book “Your death, my life”, are real and the characters there are presented with their concrete names and surnames, while only those people who badly affected his life, (mainly, those of bodies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of that time, as operative workers, investigators, police, heads of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Branch of Internal Affairs of Tropoja, Lezha, witnesses in his trial, etc.), the author was has only changed the names, giving them their real surnames.

Continued from the previous issue

Excerpts from the book “Your death, my life”, author, Esat Myftari

With residence and work in the city of Përmet

The Dibra guard had arranged his first meeting with a new executive of the Executive Committee, in the big cafe of the city. There he was told that, for all the problems, the person they just presented to him would be his relationship. But they believed that there would be no problems, since the citizens were very orderly and, perhaps, the mildest of the republic. Hence in this view

he had to call himself lucky. They also made the strange analysis that said: that the city has many Roma, but that they are the most cultured in the country; that it used to be full of pleasant erotic stories between them and the local aghallars – even with them landing from different corners; that in the bar where they were staying he would have the opportunity to listen to the legend of the Albanian clarinet, and that from time to time there also returned the also oppressive bass, Mentor Xhemali.

Even the first secretary was a Roma, a gentleman in behavior and speech. In short, that he had descended into a city for greed. Finally, they informed him that he would be temporarily sleeping in the new city hotel and that he was assigned to work as a normist in the NBSH, whose buildings were located across the Vjosa River, near the iron bridge.

Ridvani thanked them for the detailed information and expressed confidence that he would spend quiet days after the not insignificant disturbances caused by the displacement and separation from family and friends.

– What caught my eye since we were approaching the city – said Ridvani – was the river that was resembling the Lumbardhi of Peja.

“I think there are similar mountains,” added the former Dibra guard.

“Maybe, even though they look lower and without gills,” Ridvani replied.

– In the district of Permet you have all the landscapes – the liaison officer intervened.

– How good! Cried Ridvani.

At the square table with white cover and served with barrel beer in small mugs, they sit full two hours. But no one asked him about Peja. Even Ridvani did not consider it reasonable to uproot her image and put it in front of your eyes as disinterested people that they were.

When they were parting, the companions wished them good health and new luck.

Ridvan was placed in a hotel, on the second floor, in a separate room. It was the first night that there would be no one on top and that from now on he would divide his free time according to his desire. But this first night, in his memory, would enter as a night of torture: in addition to the buzz, it was the bug army that attacked him from all sides, and he, unaccustomed to them, was struggling to one side in the other until he took the chair and took a seat at the window they opened and was begging Vjosa and the surrounding acacias to bring him some freshness.

The company in Përmet with the famous translator, who also recited Fishta!

The next morning, as he was washing his eyes in the bathroom, he heard a reciting voice behind his back:

Marash Uci and Uc Mehmeti

It had fallen into the sea

There were no properties of the king …

Ridvani turned his head in surprise: Fishta in

Permet! He saw a man in his fifties, small and weak, with teeth covered in gold who laughed heartily and welcomed him to his home country. After talking quickly on foot about the fight against bedbugs and the sleepless night, they went down to the café for acquaintances and chats. They called him Ziso Vangjeli. He told her that he was originally from Permet and that he left for America at the age of thirteen, during the time of Zog. There he had graduated from history school, and the Allied landing in Normandy had found him mobilized as a major in the U.S. Army. And since he knew French, immediately after the war he was offered a good job at the American Cultural Center in Paris, where he had stayed for fifteen years. At the end of this not insignificant experience, the beginning of his sorrowful vicissitude began. The poet remained single and sensitive, he had been seized by the longing for his homeland and, with the knowledge he had accumulated, he had thought of doing measurable services only for his own place and with the dignity to be forgiven by the homeland. So, he went straight to our embassy in Paris and expressed his desire for repatriation. He had also said that he wanted to donate his very rich library to the University of Tirana. Even our ambassador was not far behind: he had congratulated him on his patriotic gesture and, aware of his rare abilities, had promised him that he would be appointed lecturer in the chair of English or history, a job he had in hand to solve it. Ziso Vangjeli that day had climbed the stairs to the seventh heaven and had undertaken all the preparations to transfer his books to Tirana within a month. The warnings of his colleagues about the ambassador’s promises and the suspicion that he was going to a country that did not match his liberal upbringing and that breaking the official word there was a sign of wisdom and not wickedness of character were in vain.

During our story, Ridvani had remained silent and was following him attentively, justifying himself: so even people with so much horizon and life experience are making such elementary mistakes?!

At this point in the story, Ziso Vangjeli stopped and addressed Ridvan with a tearful look:

– I bored you?

– Not at all – Ridvani hurried to answer.

– How happy you are, that you are at the beginning of real life!

– Thank you!

– Do not forget one more thing: whatever they tell you, know that here you are not a foreigner and that you enjoy the inalienable right to blood!

– Have you struggled to get a name at university?

– No, it is a final decision to stay here until the end. But I’m already used to it. After all, it’s my hometown and I’m slowly turning sixty.

In the days that followed, they became involuntary friends, despite the age change, because other people were not approaching them. They really smiled at him with the idiocy of masks, but no one was taking any steps towards him. This had happened to Zisos in the first phase as well, although there were people of his own tribe. Consequently, in order for the Davarians to get a little bored, they searched with their minds and imaginations and, finally, found their solution: from time to time they would go out to the nearby mountain in the afternoons, hold a birch in their hand, fall on the sticks between small rocks loud nonsense expressions, which were scattered through the trees and streams like primitive echoes. Then, at the end of this walk, they would usually go down to a small tekke with the cold water of the surrounding cypress and indulge in conversations on old topics from the Ottoman period, which the dervish had in mind. As for the time when he would be alone in the room, Ziso Vangjeli gave a piece of advice to modern American psychologists: to take newspapers and tear them by force and to exhale rhythmically from inside the lungs. It’s a good way of unloading and balancing. I used it often in Pennsylvania and Paris, he had told her.

After about three or four months, another habit was revealed to Ridvan that even Ziso Vangjeli the erudite did not know how to give dum: when he walked alone on the sidewalk, he had to count his plates. He chose the even number as his favorite so he was careful not to scratch the single plate even with the edge of the shoes. Even when it happened that he broke the sacred rule, he would go back and start walking on that part of the sidewalk again. Worried about this strange and unknown avoidance, Ziso Vangjeli said to him: listen to Ridvan, when you go out on the sidewalk now and then, bring your mind to some joyful event of life and give it up so that you forget everything around you. After all, you are above everything around you, you are a young man with an ideal, a rare thing today! And all these others are in the service of their body and of an insidious instruction. Therefore, hold fast to the book of social neglect!

Translator Ziso Vangjeli’s stories about Lasgushi

This was the first manifestation of Ziso’s political color, but which came out almost violently and which, in a way, was the cause. Ridvan was removed as if he had not heard anything.

“But the bookstore is poor,” he said.

– No worries, I have books.

– Like that?

– They did me a favor: they let me go and pick up books from my donated library, which is located on the premises of the French department.

– Oh, how good. You also have the opportunity to meet people of your rank.

– Every time I go, I visit three people: Lasgushi, Çabej and Kokona.

– And?

– We always have controlled, kind and understanding conversations. People who know Europe and its culture by heart. In addition, I am very happy that these two help Lazgushi, who is quite close.

– I will say an episode about him during graduation and, if he finds it appropriate, please tell him.

– Hey, I’m very curious. Lasgushi in Kosovo schools!

– At the matura, when the professor was talking to us about him, they relied on Shuteriq’s text, he treated us as the representative of art for art’s sake, which meant the poet detached from the people’s troubles, locked in the “fidget tower” almost reactionary. I objected to what they said in front of everyone: for me, he is part of the cream of Albanian poets and I like him very much. I had just read “Dance of the Stars” and I was fascinated by it. The professor got angry and turned to me:

– And who tells us so, a young man who still wears a T-shirt with bows on his elbows!

– But when we do not have more clothes in the clothes – I answered – what will we need? Professor, it seems to me that Migjen was deliberately whipped for Fishten and Lasgushi.

Ziso Vangjeli slapped his palm and said: good luck, you have dropped the point!

A few days later, Ziso brought two books by Racine and Moliere and a monograph on the French Bourgeois Revolution. And, as he told him that he had been several times to the places where the famous events of the time had taken place, he told him that his weak point was not Robespierre, but Saint Zhyst.

Ridvani, after glancing at three well-bound books, in soft, pocket-sized paper, asked:

– What about the literature of the time?

Ziso laughed.

– Do not ask them, because they belong to the magic box of the Index.

Locked in the room under the company of books that were found on the dusty ceiling of the bookstore!

The bookseller informed Rivan that on the ceiling of his warehouse there were books being thrown here and there, but that they were still kept in the inventory of the deceased. Ridvani expressed a desire to see them and they went there. When they climbed to the ceiling, the bookseller opened the glass roof lid and sunlight flooded into the space with heavy air. The titles of famous books were coming to his mind, some of which he had read when he was in Kosovo: “The Idiot”, “White Nights”, “Kumari”, “Ana Karenina”, Chekhov’s novels, Pushkin and a received other translation, especially from German literature. He found there even the correspondence between Goethe and Schiller, inserted in a large volume.

“Here is one of our treasures,” cried Ridvani with unbridled joy.

But the bookseller did not show any enthusiasm. He told her that, even in the inviolable days of friendship with the Russians, there had been few of their readers, except for one officer or intellectual to be educated there. Russian had hardly found its way, there was something hindering this language for the Albanian, he assured.

In the end, Ridvani bought a good handful of these books at ridiculous prices.

When he got home, he sniffed them for ventilation on the small balcony as they were our mold dust. The two roommates, NBSH employees, were following with some surprise his zeal for those books that time had punished badly enough to lie on the ceilings – well, until yesterday with such refinement! Both were from a remote village. Their arrival in the city was called a great success and the candidacy for party member, as their big step towards the final success. In the few discussions that took place in the early days, Ridvani saw that it had to do with their close, one-sided culture. They remembered a few Russian words, but when they brought Nina-Potapovna’s two-volume method into the room, they laughed and said sarcastically: Oh, Potapovna, damn it, how tired we are! Ridvan, still in Peja, was pleased that they were underestimating the Russians – ideological controversies with the BS were at their height – but he was also sorry for those unprofessional attacks on these Russian colossi. In fact, he himself had never thought that he would devote any minutes to Russian, but now that that language has sprung up as the sole source of the most elite reading, he diligently followed the text. And he quickly realized, like a Jordanian in his comic dialogue, that, even without that method, he knew half-Russian, thanks Serbian language. Thus, within six months, he was now able to use the available books. He read mainly at the cemetery, across the Vjosa bridge. He sat on the deck chair in front of Pascal’s “wounded soldier” and read for hours, without being disturbed by a living person. And the dead – some of whom were even mentioned in newspaper memorial articles – slept in the sleep of eternal oblivion. Permet tombs were well arranged, with drandofiles and chrysanthemums everywhere. Even the birds were not absent through the branches of the trees with their joyful leaps and blooms.

In fields with cooperatives, measuring rates with compass!

In the tombs, too, Ridvani usually rested even when he returned from the field, where he measured the works of the co-operatives, as they were near his office. In these cases, he did the boring part of the job: any correction of notes or necessary reconciliations through the crumbling fifteen-day lists that those in the office called “condition lists.” And while working in the field – his task was to measure the linear meters of the works with a wooden compass – he had the opportunity to get acquainted with some curious things. Ridvan was greatly impressed by the way the workers (the vast majority were women): they took the soil of a mining area and covered the rest of the untouched with it and then, with the outer side of the waist, made flattenings across the surface. Especially women and brides reminded him of the cats that, after discharge, with their paws try to cover their excrement. Ridvani was left with no choice but to return to work or report to the directorate, but then surely a small spy would have come to himself and others who had come from the side to ruin human life. But even if he left this job in silence, it seemed to him injustice and abuse of office.

Then, as he took this matter with him, he judged that the best thing would be to suspend the reaction for a while in order to have a clearer picture of the matter. Over the days, surprisingly, he noticed that his reports on the amount of work being done were not being challenged by any of the specialists, and that the data reported to him by the NBSH chief economist were also subject to the operations of the Executive Committee. other, with pencil on the table, away from the real situation on the field. The next thing that hit Ridvan hard was eating lunch in the shade of the trees: the workers were piled up and exploded in gas and spikes over the exemplary equality between them. Their menu was the same: bread, tomatoes, cottage cheese or butter and buttered butter. it diets really terrified him: not that there was no poverty in his homeland – Kosovo also had days of famine and all sorts of shortages – but what he was seeing here was something every day with no prospect of improvement! So, he began to understand why women’s hands were soaked and why brides’ skins and faces dried up within a few years, shriveled by the sun and wind. It was a premature aging, which surprised even the sky! And the moment came when he congratulated himself for the restraint he had and was not reaped in the name of honor of duty! He also realized that there was a thin network of “mining”, woven with invisible thread, which coexisted with the official advertisement in the Albanian society. As he was convinced of this truth, he made the final decision: you, Ridvan, said to yourself, there is no need to do these things, because no one cares what you think, so do not be more Catholic than Papa!

In addition, when he sat with them under the broad shade of a plane tree and they were chatting, he began to see that those people, shutting themselves in front of him on the street, here too could drop their tongues a little. His astonishment did not end when one of the workers, perhaps to open the curtain a little of an absurd time, recited the anthem “Hey Slovenia”, without understanding a word of content. And to reinforce it, another showed that his father had been a partisan in Drenica, Kosovo, and that he was surprised why Kosovars there had refused to enter the battle against Albanian partisans. But when he was touched by what he heard, he was asked a more thoughtful question, and they gathered together like hedgehogs under the thorn bush and made it clear that he should not prolong it.

In the company of graduates exchanging books and…

However, for all this, now historical reality, it was noticed that there was not the same affiliation between them: the Orthodox part was more contained in the devilishness of “Yugoslav betrayal” and most were satisfied with the expression “that was the time”; while in the rest of the Bektashi, he had encountered 3-4 Dushans, who had long since deleted the first names in the municipal registers, but in everyday life did not oppose their use, even practicing it as a pastime.

But April was not like January: cold and evocative. It came with blossoms of almonds, apples, mimosas … which overwhelmed the city with pleasant and invigorating aromas. And for Ridvan, April had a surprise with a youthful smile. One day, when he was returning home from work, at the end of the bridge, he saw the lonely and melancholy shadow of the graduate he had borrowed days ago the novel “Fathers and daughters”, a book that Ridvani especially valued, because he remembered the days of his stay in Tirana.

When he approached her, she shook his hand, bowed slightly, and thanked him with all her heart.

– Did you like it?

“Strong,” she said in a trembling voice.

– We are glad, I also read it two or three times, but in completely different circumstances.

– I believe you have someone else?

– Of course, I will look and choose one, I believe, just as beautiful.

They set out for the road leading to the city. But when they were taking the turn, she suddenly and sharply said:

– Excuse me, here we are parting, this is a province!

Ridvan nodded, clasped her hands, and she walked away. But, after a few steps, they caught each other and turned their heads back and laughed lightly.

At home Ridvani glanced at the book and was amazed: on over ten different pages, in the margins of the book, she had written Ridvani’s name and her own, caught with a binding line. But in the Cyrillic alphabet! “Eu,” Ridvan murmured to himself, “this is taking me for a Yugoslav, like the others.” That Ridvani was bored those months with the explanations he had to give to people, especially young people, that he was like them, Albanians, but of Kosovo. And yet, that connecting line revealed something wavier and piercing than an inconvenient mistake. Only now were the jokes that she had sent to her on the street or on the basketball court, where she went to attend the trainings of the women’s team, becoming clear. He was probably the only dog that was showing that there could be no dividing curtain between him and a native. Or as a cause was the miracle of an ancient chemistry?

Ridvani finally decided to accept the offer so delicately wrapped, chose Gollsward’s “Apple Blossoms” and the next day, convinced that it would appear somewhere near the bridge, took it with him. She came out of the office one of the last days and, as soon as she crossed the outer threshold, she saw that she was wandering up and down the street yesterday.

When they met, already with a sense of closeness and mutual obligation, Ridvani said:

– I brought you a wonderful story.

– They told me about your literary taste.

They were afraid that he would not leave in a hurry like yesterday, he said:

– Do you interrupt work tonight at 7 o’clock at Guri?

She said “yes” without thinking at all and left with quick steps.

In the evening, perhaps because he was in his prime, when political orders are an unbearable annoyance, he came in time, with all his prosperity, to Guri. It was thrown at their necks without greeting them well, even though it was their first meeting. Ridvani went to the slide, to quench his cravings – he had been a monk for almost a year – he stopped especially at her strong neck and chest, which even on the basketball court were conspicuous and coveted by spectators. Then when their passions sold out a bit, they also talked about her condition. She informed her of the family’s shock at the connection – she had not kept her sympathy for Ridvani a secret, leaving this foreign boy alone as a half-ghost, but refused to talk about the motives for their opposition. The main thing is that I am ready for everything, she said with a kind of heroic courage!

Their secret meetings did not last more than a month. In the days that followed, he stopped her on the street and tactfully, even with a look of plea, said to her: Comrade Ridvan, please, leave my daughter! Not because he has the problems of graduation, but you have to understand us … But do not remember that I am so wild! But my husband is an officer!

Ridvani remained frozen: he did not think that this intervention would come so soon, so he replied, without prolonging it, according to merit: it will be done as you say, honorable lady. Don’t worry!

Ridvani knew it was impossible to know what had happened between them, because on other days she did not appear at the end of the bridge, nor at Guri, even for an explicit conversation. The heat rain had stopped and Vjosa was charged with a new mission for him. She, Vjosa, was accepting it with generosity and equality: she was refreshing the naked bodies of the citizens with her abundant water. Ridvani chose a rather large stone, with a flat top, on the side of a basin a little deeper than the others, and from there he dived or lay on his back on the surface with full waves. But, as he went there for three – four days of climbing, no one approached him around. Moreover, after a few days, the children had started whispering: “do not go there, because it is the stone of that Kosovar”, a call that was respected as an official order!

But as the days went by, he became more and more convinced that he was playing with the brunette graduate full of imagination, they started it as a pleasant game, it was something more serious. He had not even foreseen that she would turn into a small wound that was secretly expanding and risking spreading to her body and thoughts. How could he not have taken into account that it was the first Albanian gentleness that was integrating it into normal life, after our spiritual upheavals both in Kosovo and during the seven-month stay on the secret basis. So, he started going out more often to the city café where the clarinetist Laver unfolded his magic. He sat down at the corner table and ordered a large mug of beer, and for his appetizer he chose brown cheese and olives as a wonderful combination typical of the south that he was enjoying a lot. But even this new practice was not bringing him any consolation or forgetfulness, because it was highlighting his status: no one was coming to his desk, not even when the others were fairies. Eventually, the feeling of neglect began to weigh on his coldness and plunge him into the well of all sorts of doubts, so he decided to give up this possible entertainment as well. He even asked Ziso Vangjeli to forgive him for not going out with him in nature for some time.

The news that he had won the right to study

At the end of June, the first positive change took place. The friend of the office, who had been very quiet all the time, was starting to open up to him like a bud, to enliven and promote various topics for no apparent reason. One day, he went so far as to invite him to visit the Alipostivan tekke, where he served him a roast lunch with grilled meat. As the god of lead, he was keeping up with the conversations and was so overwhelmed that he had forgotten that even his friend could have some story to tell. According to his lecture, Permet was a national center because the Frashëri brothers came there and why the Permet Congress was held there. When Ridvani made the timid attempt and reminded him of the League of Prizren and Peja, it was like talking to him about the history of distant Troy. Ridvan then saw fit to make no objections to him, because it seemed to him that even this lunch had something dubious inside, and that it was not merely human generosity.

The next day he was summoned to the Executive Committee and communicated that he was ready to go to Tirana in mid-July, after he had been granted the right to study.

Ridvan was now 25 years old. He remembered that the first time he went to study in Brograd, he was 19 years old, they were filled with all kinds of dreams. It was the time when the series of Albanian graduates who were spreading throughout Yugoslavia for studies had just begun and their escort was accompanied by many pohe: cousins and friends came for escort and the train station rang full of joy. But now he had a somewhat sluggish mind, and the curiosity for systematic knowledge might have been more than he feared. However, he was glad he was going to capital, where the variations would be greater and where he would meet some of his classmates.

On the day of departure, only Ziso Vangjeli came to escort him to the bus station. He gave her something wrapped in paper with the prayer that she would open it only along the way. But when he got on the bus and took one last look at the city, right in the corner of the house of culture, he investigated the graduate where he was doing it like a handkerchief. Ridvani replied that he rests his 5 open fingers on the glass and did not take his eyes off it until the bus started, they convinced him that he was leaving behind forever the magic of a summer night.

On the way, as soon as they crossed Këlcyra, Ridvan could not bear it anymore and unwrapped the small package: without four mobsters and a piece of paper folded under them. He opened it in a hurry: it was the poem dedicated to Lamartine’s time, he wrote it with Ziso’s hand, which he read with wet eyes:

And temps, suspends tons vol!

et vous, heures propices, suspendez votre cours!

Laissez-us saves the rapid rapids

the most beautiful of our days! •

………………………..

O time, suspend your flight

And your happy moments, suspend your flow!

Let’s enjoy the quick pleasures

The most beautiful of our days!/Memorie.al

Continues tomorrow