By Dalip Greca

Part Two

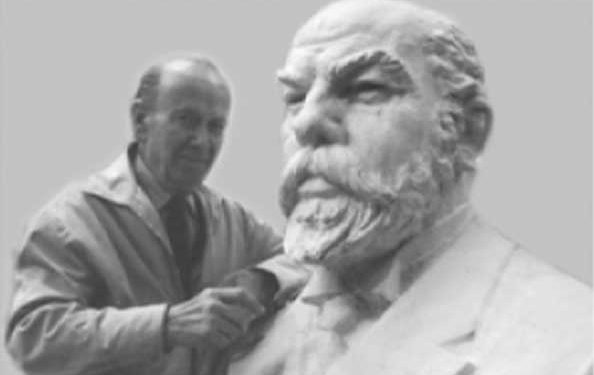

Memorie.al / Odhise Paskali are undoubtedly one of Albania’s mythic artists. His talent attracted the attention of the authorities of the time, who sent him to study in Italy. Paskali emerged as a versatile, multidimensional artist. We find his name in the early 1920s in many newspapers of the period – within Albania, in Italy, in America in the newspaper “Dielli,” in Bucharest, etc. He appears as a poet, a storyteller, an essayist (having created more than 800 essays), a critic, and a translator, while simultaneously bursting onto the scene as a sculptor. “The Hungry,” “The Man,” and “The National Warrior” are precisely the pearls of Albanian sculpture that were realized in the 1920s. To bring the full figure of this mythic artist to light, we invited the artist’s daughter, Florina Paskali, for an interview.

To be continued in the next issue

– Ms. Paskali, can you provide some information for our readers on how your father found his way toward sculpture a century ago?

As is known, my father studied Literature at the University of Turin. There is a 1985 publication, “Traces of Life”, which details his life path in depth, but as is known, the censorship of the time truncated it, and what my father intended to convey did not emerge in its entirety. I will republish it once more. But returning to your question, it was no coincidence that my father went to study. He had been noticed for his talent since childhood. He was an intelligent child who had a natural inclination.

He wrote that he had been using plasticine and a chisel since the age of five. Eventually, he caught the attention of domestic and foreign authorities, who took him and sent him to school. In fact, according to my father’s own memoirs, he recounts that an Italian officer became the reason he went to Italy for studies. Thus, the first sparks of his talent were shown since childhood.

– Odhise Paskali’s chisel has carved heroes of freedom, fighters of the pen and the rifle. There is no historical period that does not have its representatives in Paskali’s art. How would you comment on the fact of your artist father’s national orientation?

I feel sincerely good when I see the heroes of the nation that my father’s chisel has carved. To be honest, whenever I go out in Tirana and stand before the Skanderbeg monument, I feel moved. Thousands of people pass there, and often among them is me, the daughter of the artist who immortalized the hero. Even when I receive an unexpected invitation: “Can we take a photo with the artist’s daughter in front of the hero?” – again, I have felt manifold emotions. For me, my father was a worthy successor of the Rilindas (National Awakening figures), who served the motherland with soul and heart.

He was also a man of sacrifice. Consider that “The National Warrior” was cast in bronze in Italy, and it required great expense and immense effort to bring it by ship to the homeland and place it in Korçë. The same thing happened with the placement of the “Flag-bearer” in Vlorë, or the “Çerçiz Topulli” monument in Gjirokastra. Only an artist with a great heart could undertake such actions.

Just as he saw Italy, which had every historical period immortalized in sculpture, he likewise sought to bring the same thing to an Albania submerged in backwardness. With this love, he worked for 62 years; these were the relations he established with his Motherland. His art, in fact, is more outside than inside galleries. He placed his work in the public spaces of the cities.

– Little has been spoken about Paskali’s nudes; what new information can you bring to our readers?

Paskali was an artist who created during four regimes. Regarding the nudes, I would say that he was the first to place the first nudes in public environments. The first nude in a park is by Odhise Paskali; I do not know if you have this information or not.

Even in Albanian newspapers, there has been long talk about the permanent absence of nudes in public parks. This comes from a lack of information. In the Royal Palace, since the time of King Zog, there is a large and beautiful sculptural work titled “Fertility” (Pjelloria) – it is the nude woman with two children at the fountain, which I have included in the current publication.

– Given that you had a close spiritual relationship with your artist father, can you say which his most beloved work was?

I think that the “Bust of Skanderbeg” is one of the works to which my father dedicated a lot of time and a lot of work, and he always nurtured a special feeling for it. He was occupied with the “Skanderbeg” bust for nearly 40 years. To create a hero of those artistic dimensions, he studied a lot and created many variants until he realized two of his most representative works: the “Bust of Skanderbeg” in 1939 in Kukës, and the “Skanderbeg Monument” placed in Tirana, co-authored with Janaq Paço and Andrea Mano.

In his notes, he left behind Skanderbeg; he left a wonderful model, it is the “Young Skanderbeg,” which is a giant work of magnificent dimensions. Regardless, he was very satisfied with the “Skanderbeg” Monument in Tirana, as it has been evaluated as the most beautiful monument in Europe. I feel sorry that in this time we live in, under the difficult conditions of the market economy, some so-called artists, who have no connection to art, are targeting this work as a source of money – taking advantage of the fact that “Skanderbeg” and the “National Flag” are preferred as symbols – and have started making busts.

I feel sorry that copyright is not respected in this mess, and plagiarism and amateurism are damaging true art. Let us hope that the law on copyright will soon teach a lesson to the dilettantes and speculators. Albanian law actually recognizes copyright until 70 years after death. Under these conditions, I will fight to be in defense of my artist father’s rights.

– Before making the bust of Enver, your father had modeled the bust of Mussolini, and before that of Mussolini, he had realized the bust of King Zog, the “rival” of the dictator. Why do you think Enver Hoxha tolerated your father?

I think that my father was a great, talented artist. He lived through several regimes, and each of them needed his talent and would not have found it easy to oppose him. Great artists, from Mozart to Michelangelo, have works made to order. He passed through four regimes, and each of them needed his talent. Each of the chief rulers wanted to be immortalized in a work of art that bore the authorship of Odhise Paskali, who was so highly regarded in the West.

Living near my father, I experienced his spiritual, human, and artistic concerns from up close. Many of them I have brought to light through the publication, and many others are expected to be clarified in the future. My mission is to bring to the researchers of his work both intimate things and things they do not know.

– The press has reported cases where you have raised your voice regarding the “imprisonment” or damage to Odhise Paskali’s works. Have you managed to “UN-imprison” any of them? What is the truth?

The transition has its unpleasantries; the wave brings to the surface speculators, dilettantes, anti-culture, and anti-citizens, who think nothing of placing a building or a shop in front of the bust of a great Rilindas, or taking the bronze to sell it. But there is also egoism as there is meanness.

To say that there is also ignorance – in the case of the sawing of Naum Veqilharxhi’s bust for a few kilograms of bronze – I don’t know how accurate I am because a thought tells me someone guided that person, let’s call him a man in need, because he could have secured profit even from some army shell casings, which were in abundance in post-’97 Albania.

Perhaps Naum Veqilharxhi might interfere with the interests of someone from anti-Albanian circles, considering what he represents. There is no period of Albania’s history that Odhise Paskali has not immortalized in monuments. So there is also malice toward the sculptor here; by toppling the works, history is toppled. There is also professional malice.

For example, the Naim Frashëri worked by my father, or De Rada, was in a square in Tirana, an original work from 1962. The bust was removed because a square was being built, and the decision stated it should be replaced within the year 1998; we are in 2007 and the bust has still not been placed. Not only that, but now the bust cannot be found.

I have searched for it everywhere, but those who removed it just shrug their shoulders. The Municipality of Tirana says they know nothing. I do not believe it is the duty of artists’ heirs to turn into guards of their fathers’ works; the state must have its own functioning mechanisms. That is why the municipality exists, why the Institute of Monuments, the Ministry of Culture, and many state institutions exist. I think that on one hand, the chaos causes damage, and on the other hand, malice and lack of professionalism, along with egoism.

– Regarding the fate of the artist after death, your father quotes Asdreni; as his daughter, after your father’s passing from this life, as the heir to that treasure he left behind, do you feel that your father is respected even after death?

Regardless of the fact that we live in a very difficult time, I have felt and often feel my father’s greatness. I have felt it in Pristina, in Peja, where the art school bears the name of Odhise Paskali; people who know my father’s work, people who love art, those who know my father’s work, value Paskali as a myth and tell me that he is such a major, polyhedric figure that the nation will not see the likes of again.

Meanwhile, the mean-spirited, the small-souled, and the speculators try to minimize him, even though he is a colossus. There is also jealousy. I feel sorry, for example, that even in the diaspora, monuments of Skanderbeg are placed by amateurs, making new ones, while Paskali’s masterpiece has already received the evaluation of time. Many times, with much less expense, permission could be obtained and my father’s work could be re-installed.

– During the time of communism, your father did not lack appreciation, but as was written later, the watchful shadows also followed him. What can you say about this?

I told you that my father worked and was appreciated in four regimes. He was “somebody.” My father was a formed artist and had appreciation not only in Albania but also abroad, especially in Italy. Another fact must be kept in mind: until 1941, he stayed in Italy, where he had his home, his studio, and everything an artist of those dimensions needed. He was not formed in the schools of the East, but was the only one from the school of the West, which constituted a reason to keep him under surveillance. I have reflected only one fact in the book. The fact that my father died unexpectedly needs no comment./Memorie.al