Part One

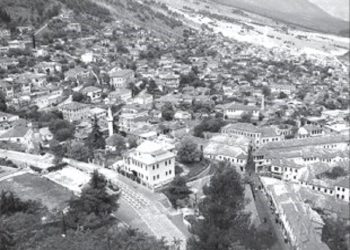

Memorie.al / Favorable winds were blowing in Czechoslovakia. The weather promised spring. Alexander Dubček, having come to power, was undertaking reforms that promised the democratization of the country. Unfortunately, this period of hope lasted only a few months, from January to August 20, 1968, when the country would be occupied by the Soviet Union and the so-called “Prague Spring” would come to an end. But what was happening in Albania in the meantime? Lawyer Spartak Ngjela describes this period in his book “The Bending and Fall of Albanian Tyranny,” published by “UET Press,” Volume I, Tirana 2011.

Through conversations with his father, Kiço Ngjela, contemporaries, and fellow prison sufferers, Ngjela speaks about Enver Hoxha’s megalomania and his challenge to create another Communist International, an initiative in which it is unknown whether he truly believed, or whether he wanted to pull the wool over the Albanians’ eyes that Albania was not isolated. “Meanwhile, we who lived close to Enver Hoxha’s court accurately observed that the entire old guard living around him was not at all enthusiastic about the Marxist-Leninist parties in the West.

They were unconvinced, and the opposite had occurred: instead of taking this as a sign of Enver Hoxha’s ‘greatness’ as a doctrinaire, they had taken it as a sign of his weakness, for a failed endeavor. I noticed this in my father too,” writes Ngjela. Those who had heard something about what was happening in the world understood what was happening in Albania. “Broadway was buzzing with jokes and humor against Enver Hoxha. But the ‘Rhinoceroses’ had also greatly intensified their fight through leaflets,” Ngjela recounts, pausing briefly for a conversation with Vera Bekteshi, one of the victims of the daci-baos [referencing a Chinese cultural term used in Albanian communism]. Fifty years after the “Prague Spring,” some memories also come from the winter that held Albania. (Al. Mi.)

THE HOXHA EMPIRE AND THE PRAGUE SPRING

I

At the same time, Enver Hoxha had begun the work of creating his empire, which would undoubtedly be Marxist–Leninist. It would take him about ten years to fully stabilize this “empire.”

It is unclear what psychological impulse prompted him toward this decision. The entire history of ideologies is a history of schisms, therefore, up to this point; everything seems to proceed within a normal historical flow for its kind.

It is known that there have always been interests of leaders in all schisms. Numerous have been those dogmatic leaders who have exerted terror against society in the name of the ideology or religion they have led, even though they believed in that religion or ideology less than anyone else.

This is the sad history of the irrational human mind and the powers that have always relied on the fanatic part of society, meaning, that part that knew nothing about itself and the world. Enver Hoxha could not have been a representative of any real faction in the global communist movement.

He was a politically clever mind in the game for power, and, as the founder of an ideological movement, for his own interest, he managed to detach his own “church” from Moscow. Then, with the help of his frightened and subjugated followers, he thought to keep the “church” only for himself and to treat it as a sacred and inviolable object, because this was the source of political power.

The global communist movement arose with the hope of a revolution for social equality, but practically it ended up in that mixture of humanism with terror. In this mixture, those who had been humanists sui generis and who genuinely believed in that doctrine, fell victim to the terror wielded by their leaders, who, most of the time, had no connection to either humanism or the doctrine.

Thus, for this case too, Hoxha began his work for the creation of a “Marxist-Leninist empire,” also using the thesis of a global proletarian revolution.

This was an alibi that Hoxha created to give authenticity to his own movement, as well as to establish the “doctrine” of detachment from the socialist camp. For this reason, the alibi had to have a dual use: both vis-à-vis Soviet politics, but also before Albanian communists, especially those around him, whom he had actually decided to discard from his empire, which would undoubtedly be Marxist–Leninist.

It would take him about ten years to fully stabilize this “empire.” It is unclear what psychological impulse prompted him toward this decision. The entire history of ideologies is a history of schisms, therefore, up to this point; everything seems to proceed within a normal historical flow for its kind. It is known that there have always been interests of leaders in all schisms.

Numerous have been those dogmatic leaders who have exerted terror against society in the name of the ideology or religion they have led, even though they believed in that religion or ideology less than anyone else. This is the sad history of the irrational human mind and the powers that have always relied on the fanatic part of society, meaning, that part that knew nothing about itself and the world.

In this mixture, those who had been humanists sui generis and who genuinely believed in that doctrine, fell victim to the terror wielded by their leaders, who, most of the time, had no connection to either humanism or the doctrine.

Thus, for this case too, Hoxha began his work for the creation of a “Marxist-Leninist empire,” also using the thesis of a global proletarian revolution. This was an alibi that Hoxha created to give authenticity to his own movement, as well as to establish the “doctrine” of detachment from the socialist camp.

For this reason, the alibi had to have a dual use: both vis-à-vis Soviet politics, but also before Albanian communists, especially those around him whom he had actually decided to discard, and the creation of his empire, which would undoubtedly be Marxist–Leninist. It would take him about ten years to fully stabilize this “empire.”

It is unclear what psychological impulse prompted him toward this decision. The entire history of ideologies is a history of schisms, therefore, up to this point; everything seems to proceed within a normal historical flow for its kind. It is known that there have always been interests of leaders in all schisms.

Numerous have been those dogmatic leaders who have exerted terror against society in the name of the ideology or religion they have led, even though they believed in that religion or ideology less than anyone else. This is the sad history of the irrational human mind and the powers that have always relied on the fanatic part of society, meaning, that part that knew nothing about itself and the world.

Enver Hoxha could not have been a representative of any real faction in the global communist movement. He was a politically clever mind in the game for power, and, as the founder of an ideological movement, for his own interest, he managed to detach his own “church” from Moscow.

Then, with the help of his frightened and subjugated followers, he thought to keep the “church” only for himself and to treat it as a sacred and inviolable object, because this was the source of political power. The global communist movement arose with the hope of a revolution for social equality, but practically it ended up in that mixture of humanism with terror.

In this mixture, those who had been humanists sui generis and who genuinely believed in that doctrine, fell victim to the terror wielded by their leaders, who, most of the time, had no connection to either humanism or the doctrine.

I have never excluded the idea that paranoia might have pushed Hoxha towards this sterile passion for an empire, because at times, Hoxha showed signs that he believed himself to be a great man. This has been confirmed to me by many others who lived close to him during those moments, while Kiço always emphasized that the delusion of being a “great man” and “permanent fear” were inherent to his nature, even before he came to power.

“He was always secretive,” Kiço used to say and continued: “During those difficult times in Tirana, he never looked you in the eye, or even when he did look at you, he scrutinized you to see whether he could trust you or not, even though he never trusted anyone. But he had a mania for speaking like a great man, one who knew how to give directives, and, ever since he was 34 years old, he attempted to speak like an elderly person. He had a speech impediment and spoke in fits and starts, but he was always very attentive and successfully used the method with the person close to him of showing that he held them very dear to his heart…!

The first person to grasp this nature was Qemal Stafa. He understood, and in the last months, he always sought to avoid him. It is highly possible that they had a harsh clash with each other, because around this time, perhaps a month before he was killed, Qemal Stafa told me: ‘Kiço, I am alone, and all of you are in danger’… I could never fully understand this last conversation with Qemal Stafa, and after his murder, I never let it leave my mind.”

With the money of Albania and especially China, Enver Hoxha began to create the second schism of communism, by establishing the “true Marxist-Leninist parties” throughout the world, but especially in the West.

Logically, this undertaking completely closed the circle of his work, which had begun with the break from the Soviet Union, because, crucially, he needed this to show that he was not only not a lone warrior but was also a great man and the only revolutionary in the world. It was his old nature that pushed him to think he could lead all of humanity.

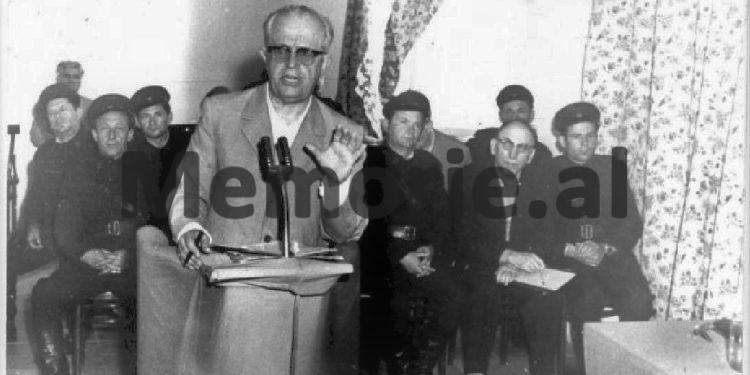

This nature of such a delusion was especially noticeable during his evening conversations at the Party Club with his people from the First Circle, to whom he now only spoke about the fate of the world and communism and no longer allowed them to say a word. But with Shehu and Kapo, he acted somewhat differently, as if they were three musketeers united by a grand goal. “I asked Mehmet,” I remember Ladi telling me at that time, when Hoxha’s parties were emerging – “I even asked him several times, but he refused to answer.”

This continued until his mother, Fiqreti, motioned to him, signaling him to drop that topic. Whereas we, in our circle, laughed, considering this ardent undertaking of Hoxha as a folly he had embarked upon to show composure towards himself and to exact revenge on the opponent. But the idea of the empire was actually analyzed for me by Zef Mala, during the time we spent frequently together in Ballsh Prison.

Zefi saw Hoxha’s tendency as a “natural propensity” of his megalomaniacal type, who thought that by entering the West with his parties and newspapers, he was somehow greatly increasing the small territory and small population of the state he led.

“He needs it to somewhat realize his delusion, because the desire for empire is still present in the human archetypes he represents,” Zef Mala emphasized then, and recalling the time and the entire movement, I am convinced that this psychological state, burdened by the emperor’s unconscious, was the central nature of Hoxha during those years, when on one hand he exerted all political and demagogic force for the isolation of Albania, and on the other hand, he increased the ranks of small parties, which held no value for the political future of their countries.

Hoxha, in fact, thought he was also building a Socialist or Communist International, just as Marx and Lenin had done, but at the same time, he found an ugly alibi, providing “proof” that he was not isolated, but on the contrary, had many friends all over the world and the world was looking to him.

He felt that the issue of Albania’s isolation was an ahistorical action and a return to Ottomanism, and therefore he presented the Marxist-Leninist movement as a kind of new Europeanism. He was diabolical to the end, because he sought to definitively dismantle the European culture of the Albanians, by intriguing them with the new fact of the proletarian revolution. Memorie.al