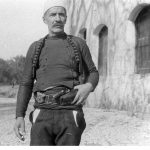

Memorie.al / His name were Isa Boletini, the same Albanian from Mitrovica who appeared in one of the most brilliant pages of our nation’s history as the right hand of Ismail Qemali. Meanwhile, the event – perhaps known only to a limited number of interested people – centers precisely on his execution on January 23, 1916, exactly 92 years ago, in Podgorica, now the capital of Montenegro. We are talking about a sequence for which few similar versions exist in world history, even those hyperbolic accounts by fantasists.

Here is the incomparable scene: “Trapped in an ambush, Isa Boletini is fired upon from all sides, yet he does not fall as he continues to return fire at his executors until the very end. Riddled with bullets, he does not lie down, does not utter a sound, does not tremble, and takes no step back, as if he were made of stone. Eventually, his wounds bring him to his knees, but he still manages to hold the weapon in his hands, firing… And at the moment his right hand is shattered, he switches the revolver to his left!”

THE PROLOGUE TO THE MURDER

The killers of the strongest man by Ismail Qemali’s side – the man who declared Albania independent – were Montenegrin gendarmes ordered by their government, while those who betrayed him (prenë në besë) were several French diplomats. It was January 1916, the exact time when Austrian troops were occupying Montenegro, encountering almost no resistance. However, the Montenegrin rulers, unashamed of this invasion and the fact that they did not resist until the end, still took care to get rid of their old enemy, the “terrible Albanian” Isa Boletini, whom they had held in isolation for some time.

According to the accounts of a relative of Isa Boletini, reflected in Skënder Luarasi’s book “Isa Boletini” (1971 edition), the final turning point in the life of the great Albanian began with the inclusion of Kosovo under Yugoslavia, following the decisions of the Great Powers of Europe at the 1913 London meeting. In 1915, the Montenegrins occupied Shkodra, and the legend of the resistance for national unification was forced to seek international assistance.

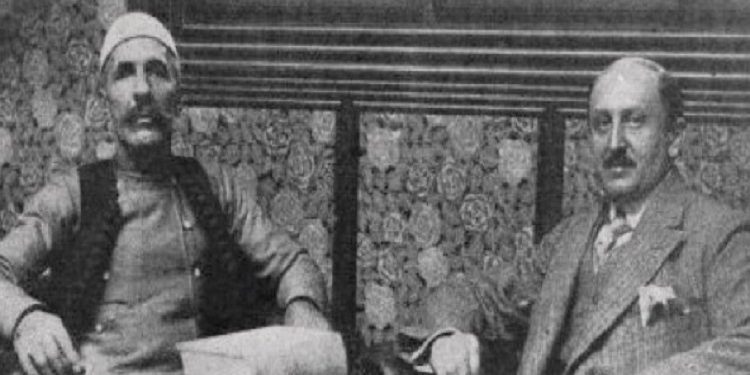

The French approached him, and their consul in Shkodra, Vicocq, told Isa Boletini and his men to go to the French Embassy in Cetinje – then the capital of Montenegro – from where they would receive visas to travel to a neutral country. This is precisely where the plan for the execution of the great Albanian began.

Boletini’s men had noticed a strange connection between the French and Montenegrin diplomats in Shkodra, but this would only occur to them later. Regardless, Boletini and his entourage arrived in Cetinje and subsequently visited the French embassy, where they were shown a telegram presented as an order from the French Foreign Minister to escort them to a neutral country.

Meanwhile, the British, more generous, invited Boletini to take him under their protection, but following the “laws of the mountains” (the Code), he preferred “the friend who opened the door first.” A few hours later, in the morning, Isa Boletini saw that the house where he was staying was surrounded by Montenegrin gendarmes. The Albanians were taken and sent to Nikšić, being kept under surveillance the entire time.

THE EXECUTION

The collapse of the Montenegrin front by the Austrians during the same period finally sealed Isa Boletini’s death sentence. Montenegrin soldiers escorted him and his closest associates to Danilovgrad and then to Podgorica. On January 23, 1916, the day the Montenegrins were surrendering the capital to the Austrians without a fight, it seemed the order for the murder of Boletini and his men could no longer be delayed. The execution was entrusted to a military unit tasked with maintaining order in the city until its surrender to Austrian troops.

Here is the account of Tafili, Isa Boletini’s nephew, who survived the event, according to Skënder Luarasi’s book: “About 80 gendarmes had laid an ambush on both sides of the Ribnica Bridge, across from the prefecture, near the Catholic church. My two brothers and I, following the messenger’s notice, were returning home to our uncle (Isa); the patrol at the head of the bridge, waiting for my uncle’s arrival, stopped us. When the officer ordered the halt, the gendarmes, with rifles ready to fire, asked: ‘who is Isa Boletini?!’ But the officer intervened, telling them: ‘Do not fire, none of them is him!'”

However, the three brothers had no opportunity to warn Boletini of the Montenegrin decision, as they were forcibly locked in a house under the threat of weapons. At this time, Isa Boletini, with seven others, had taken his first steps onto the planks of the Ribnica Bridge, unaware that from behind, the gendarmes had closed the path so there was no possibility of escape. “A commanding officer asked the Albanians to surrender their weapons, but Isa Boletini refused: ‘by my faith, no! I have surrendered them neither to King nor Sultan.’ And he drew his weapon. The first to fire was one Pero Burić, from Vasović.”

Immediately, Isa Boletini and his men responded in kind with two revolvers in their hands. Within minutes, surrounded on all sides by dozens of gendarmes, everyone was killed: Isa Boletini and his two sons, Halil and Zahid (who was a student in Vienna), two nephews, Jonuz and Halil, Hajdar Selim Radisheva (Isa’s brother-in-law), Hajdar’s nephew Idriz Bislimi, and Misin Bala from Isniq. On the other side, eight gendarmes were killed and twice as many wounded. “The spectacle was observed by several Montenegrin ministers sheltered in the city prefecture,” the survivor recounts.

ACCORDING TO DJILAS

It has not often happened that Slavs write with respect about Albanians, especially those of the south. But it seems the greatness of Isa Boletini transcended borders. Milovan Djilas, the well-known dissident politician and writer, in his work “Land without Justice,” published in the English version in New York in 1958, writes with respect about the Albanian. Many have compared this work to Sholokhov’s “And Quiet Flows the Don.” Here is how he describes the moment of Boletini’s murder:

“Isa’s battle with his volunteer soldiers had not lasted long, despite the fierce heroism of the Albanians. From this blow, their leader and his devoted followers had fallen. Isa’s closest people were liquidated, and the others were scattered in all directions. Isa Boletini was killed, but he had fought bravely, even for a long time, despite being left alone on the main road. Even wounded, he had risen to his knees, and though he lacked the strength to hold his rifle, he fired his revolver to at least kill one of the enemies before breathing his last. My father had rushed toward him, and the unconquerable Albanian had switched the revolver to his left hand, but he had no time to open fire.

A soldier took aim at him, and Isa fell to the ground. My father rushed over, and Isa looked at him with his large, bloodshot eyes, said something in his native language, and at that moment passed away. My father took his long Mauser with a silver-decorated handle and kept it as his most precious memento. Surprisingly, even we children felt sorry and felt grief, mourning for Isa Boletini. Even my father felt sorry, though he was proud that he had been killed by his group.

This was a special kind of grief; it was more an admiration for a fearless hero of Albania, who had fought until the end in an open field, in the middle of the great road, without pleading to anyone and without forgiving anyone – standing straight, unprotected. Admiration for him was also part of our grief. If a man must die, it would be good to fall as Isa Boletini fell. May he be remembered forever by those who saw him and those who have heard of him!

Much later, we told our father and teased him about this, as we had read that Isa Boletini had died in Shkodra. My father did not accept such a thing. For him, it did not matter much if it had been Isa Boletini himself or one of his officers; the main thing was that the Albanians who had fought in that battle, and especially their leader – who could be no one else but Isa Boletini – had been killed. My father had been told that this was Isa. And that was enough for him; the fact of his fall was proven forever by the fire of the rifles.”

THE BURIAL

When questioned by the Austrian authorities, the Montenegrin ministers justified themselves by claiming they had information that Isa Boletini would provoke events to burn and loot the city. According to them, he was killed while attacking the prefecture in a clash with army patrols. The direct organizers of the murder were the Minister of War, General Vešović (King Nikola’s brother-in-law), the Commander-in-Chief, General Janko Vukotić, the Minister of Internal Affairs, Plamenac, the Prefect of Podgorica, Ramadanović, and others.

The bodies of Isa Boletini and his men were initially placed in a room in the prefecture, where identification took place. The burial was held in Podgorica two days later with the participation of thousands of Albanians residing in the area. Nasuf Dizdari from Shkodra gave a speech before Boletini’s coffin was lowered into the ground. Nevertheless, no one believed the news of Boletini’s murder, as it was not the first time reports had falsely claimed his death. Similarly, an official communiqué from the Austrian army, reporting his death “during a clash with the Montenegrins,” was not believed.

Isa Boletini’s nephew, who bears the hero’s full name and lives in Tirana, provided the documents that made this writing possible. The descendants of Isa Boletini have made it a tradition to inherit the name of the great warrior.

FROM MITROVICA TO VLORA: BIOGRAPHY OF A GREAT ALBANIAN

Isa Boletini was born on January 15, 1864, in Boletin of Shala, Mitrovica, on the border with Serbia. At age 17, he participated in the League of Prizren. He supported the Albanian National Awakening, particularly for schools, even building the first Albanian-language school in Boletin of Shala. The Turks sought the destruction of the Boletini family and especially the elimination of Isa, as they had become the main opponents of the occupation. A Turkish general, Dervish Pasha, suppressed the people of the region and burned the first Boletini tower.

The hostility toward the Serbs began in 1908 when Isa and his men disarmed Serbian bands commanded by the Russian consul of that time, supplied with weapons by Russia. After World War I, the Turks, supported by local Serbs, attacked Boletin but failed as the Turkish army was defeated. This greatly enhanced Isa Boletini’s reputation, and as a result, hundreds of other Albanians joined him. At the same time, he rebuilt the tower and the Albanian school, which are preserved today.

It must be said that Isa Boletini was at the head of the Albanian uprisings against the Serbo-Montenegrins, but also the Turks, from 1901 to 1912. During this period, his name was frequently mentioned and commented on in the press of the time in connection with the battles of Carraleva, Kaçanik, Skopje, and the Fortress of Mitrovica, where the Russian consul who assisted the Serbs in operations against the Albanians was killed.

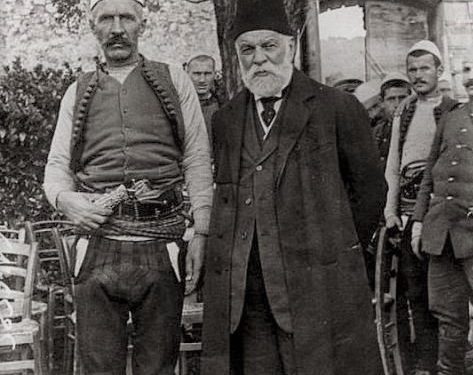

In November 1912, to come to the side of Ismail Qemali, Isa Boletini – pursued by Serbo-Montenegrins and Turks through harsh weather – covered the distance from the northernmost Albanian-inhabited edge to Vlora in record time. Here, he was charged with creating the first Guard of the Albanian Army, establishing order in several southern areas and protecting coastal zones from Greek forces.

In 1913, he went to London as a representative of the Albanian Army. In the British Museum of London, there is a portrait of him titled: “The General with the White Qeleshe.” In 1915, he placed himself in defense of Prince Wied’s government and, with the support of Dutch Colonel Thomson, created the first Albanian gendarmerie. In 1916, he was in Shkodra to organize the defense against the Montenegrins, the time when his murder was also staged.

The work of Isa Boletini has been honored at all times throughout ethnic Albania. Schools, streets, neighborhoods, and squares bear his name. There is also a special battalion of the Albanian army that bears the name of Isa Boletini. / Memorie.al