By Ahmet Bushati

Part thirteen

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

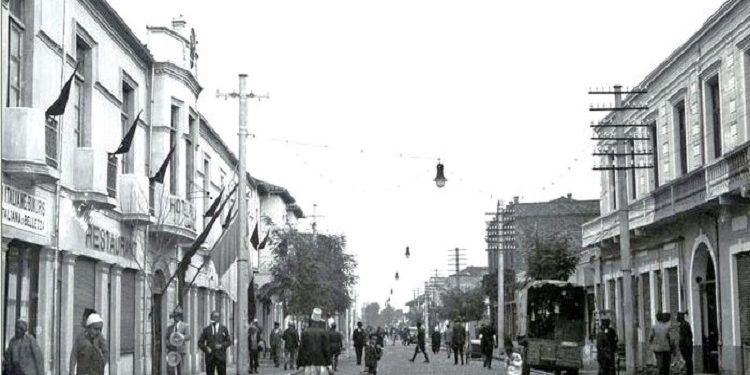

Shkodra in the first years under communism

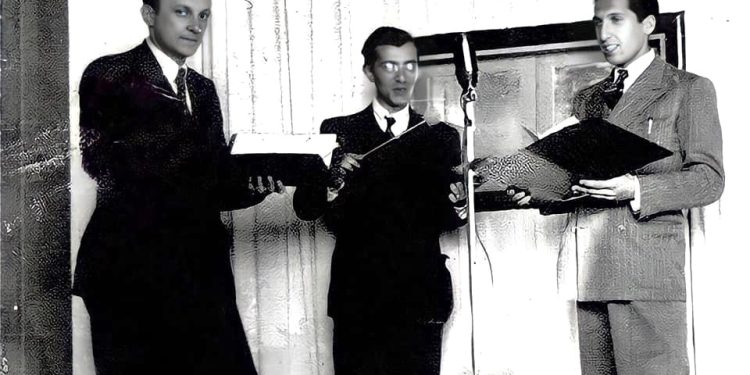

The Press in Shkodra during the First Months of 1945

The press, through the newspaper “Koha e Re” published daily in Shkodra, had the main task of highlighting the successes of the People’s Power and its continuous strengthening. Generally, the pages of this newspaper were occupied by articles that glorified the brotherhood of our people with the Yugoslav people, as well as the role played in this direction by the leaders Tito and Enver. Every day, that newspaper would also, under the most bombastic headlines, talk about the successes of the Red Army on the Eastern Front, successes that were dedicated to “the genius mind of Stalin, the greatest strategist the world had ever seen,” and the Red Army itself would call them “glorious,” “liberator of the peoples,” … of Stalin…” etc.

In honor of its anniversary, which was on February 23, a few days earlier, various associations, organizations, and institutions of the city were forced to hold meetings in which, as if in the press, they would express their deep gratitude for the sacrifices that that army was making in the name of the freedom of the peoples oppressed by the yoke of the Axis Powers, and where in closing, as a rule, they would supposedly ask the people themselves to send them a telegram of congratulations. Stalin. It is possible that such a celebration, in relation to the country, would not have taken on the same proportions and pomp as in Albania. After the press, even Greater Malsia, which still continued to emit smoke and flames for itself, had gathered and supposedly asked to send a telegram of congratulations to Russia and even to Stalin himself!

With a slavish adoration, they would talk about Stalin and perhaps equally about Tito, but with the difference that the notes about the latter would no longer be as for a superman, but as for a more humane, closer and tangible leader, whose warm hand we had felt since the War, including the help given by him on the occasion of the annoying problem of Kosovo, with “reactionary and incorrigible people”.

Also, there would not be a day that would not be wrote in the newspaper about the “reaction” and the “reactionaries”, whose denigration and excessive discrediting would never be given much space in the newspaper “Koha e Re” of Shkodra. Among its articles, a heavy style and stale jargon, carried over from the last year of the War, continued to prevail, where old and new opponents were presented as dangerous ghosts, who were trying to ruin everyone’s lives, and who in such cases would be labeled as “unprincipled”, “tricksters”, “demons” etc.

In that press, it would also be talked about the “Second Front” dominated by the war of the peoples of Yugoslavia, and about the “Western Front”, where in fact the Allied forces fought with great success under the command of the distinguished generals, Eisenhower and Montgomery, respectively of America and England, would speak to them as if with hypocritical correctness, just to get ahead of themselves.

The soul of the newspaper “Koha e Re” would be Gjovalin Luka and Arif Gjyli, who, in cases of praising or denigrating figures, would display a lot of revolutionary sentimentality, without sparing a name or an epithet. Once, Arifi, in order to prove to the public, the qualitative difference between the two regimes, the reactionary one of the past and the other, of the people, had the idea of making a comparison between them by lining up the two sides of ministers facing each other, as if they were two teams of football players, and in the end, as according to Arifi, the difference between them would be like that of day and night. Arifi would close that article with the words: “… that they were” – he is talking about the ministers of the past – “monopolizes of Albanian nationalism, tied head and ass to every occupier”.

A day would come not far away, when both the idealistic former student, Gjovalin Luka, who had once been greatly inspired by the romanticism of communist ideas, and Arif Gjyli, – one of the most active war activists in the Shkodra region and the brother and uncle of two of the city’s most famous martyrs, Esat Gjyli and Naim Gjylbeg, – would be softened by Enver Hoxha in his treacherous attitude towards them: Gjovalin would be politically sidelined, locked in solitude and under constant pressure, from which he would then, as a result, suffer severe nervous phenomena, and one day die without being remembered by anyone, while one day Arif’s hands would suddenly be handcuffed, allegedly for having attempted to escape to Greece. The tale is funny!

Thus, Gjovalin Luka, Arif Gjyli, like Xhemal Broja, Zef Mala before them, or other former communist leaders everywhere in Albania, although generally with average levels of culture, would be forced to try their luck, as well as those very ideas that they had once received with great affection, through a romantic literature and revolutionary phraseology.

Returning to the press, every achievement in any field would be advertised as very important, regularly highlighting the political factor that had enabled the success of that achievement. The press would call the fact that after a few days there would be four hours of lighting at night a success; The re-opening of a small factory would also be considered a success, also because it would no longer have the fortune of being “private”, as it had been until recently, and the construction of a canal bridge in a village would also be considered a success, always being evaluated as; “the direct result of the People’s Power”.

The first Soviet film, “Kutuzof”, arriving in Albania at that time, had a great resonance since a few days before its first screening, being called in the press as; “a magnificent achievement of Soviet cinema”. It was also advertised as an important gift that was being given to our culture on that occasion, even though it was known that the people of Shkodra had learned for many years to watch the pinnacles of world cinema in its cinemas “Rozafat”, “Gloria” and “Verore”.

From that time on, the citizens of Shkodra would only have the fortune to see films about “life” and “agricultural production achievements” among the Russian “kolkhozes” and “sovkhozes”, where peasant heroes were sacrificing themselves for the interest of millions of other people, supposedly without any regard for their own, films about which, people from the people, often leaving the cinema, would hear them say: “I put you to sleep”, or “Wow, how I slept”! Already at this time, the Albanian “stereotype” would see its ugly birth, which would be reflected without reservation, especially in the press.

Artificiality, unreality, hyperbolization, deformation or denial of facts, along with hypocrisy and falsehood, would be some of those immoral elements that the dictatorship, above all others, would demand in one way or another from its press officers. For example, the speech given in Tirana by the uneducated Koçi Xoxe, on the occasion of the first anniversary of the “February 4 Massacre”, the journalist would call “historic”, and this for the banal fact that the speech was number two in the hierarchy. The standard speeches given by officers such as Shefqet Peçi, Lieutenant Colonel Beqir Balluku and Lieutenant Colonel Esat Ndreu, on the occasion of the decoration of several soldiers for war merits, would be considered very important.

Rarely, a poem dedicated to the war martyrs by Vehbi Bala, Lazar Siliqi, or even Mas’har Bekteshi, seemed to break and soften the harsh notes of the daily press, with slogans that were both radical and euphoric at the time.

Generally, the attitude of Shkodra citizens towards the communist regime in its early days

The days that passed, carried with them more and more the dissatisfaction and anxiety of a people whose lives were darkened by recent events. It would have been a very shocking thing for our citizens at that time, who, almost every morning, would hear the barrage of machine guns coming from the direction of the Zallit i Kirit, where political opponents of the regime and, even more ordinary people, were regularly shot for the so-called crimes of the last few days, the screams and murders, as if they wanted to say to Shkodra: “Lower your head”!

More than from the city, people were shot from the areas around Shkodra, especially from the mountains. In addition to sentences of imprisonment or execution for political reasons, citizens were sentenced to years in prison and even death, even for crimes that were not political, but that that government deliberately politicized and the authors of these so-called “crimes”, calling them on that occasion “enemies” and “saboteurs” who had sought to discredit, or even overthrow, the “People’s Power”. People were punished at that time if the inspectors found in their homes even a little food above the permitted norm, manufactured goods or other things that by law should have been handed over, even if they had empty barrels, as was indeed the case in one case, which they would later report in the press.

From then on, the people of Shkodra would never agree with the policies of the communist regime; on the contrary, they would consider communism as something foreign and always bad, which had fundamentally disrupted the course of their peaceful and relatively good life.

For the realization of the communist “blind”, time in Shkodra would require them to work faster and harder than in any other part of our country, and the dictatorship here would extend its claws deeply, so much so that at the end of three or four years, it would have eliminated almost the entire former leadership of the National Liberation War of Shkodra, because as we saw a little above, by then the time had come when it should no longer belong to those who had started it, the idealists, who, as it were, would burn one after the other in that fire that they had first lit themselves.

The war against Shkodra, due to its genuine Albanian worldview and its unyielding spirit for freedom, would be constantly systematic and intense. Starting from then and continuously back, the people of Shkodra would whisper in each other’s ears: “These hours are not long”, “two months go by and these people come out, etc., etc., or even “England and America will not leave us under these people’s feet”. The fact that the people of Shkodra went a lifetime without having put the words “power”, “liberation”, and only on rare official occasions the words “comrade” and “comrade”, shows their firm disagreement with the norms of the communist regime. Thus, the word “liberation” would be remembered with disgust throughout their lives, just as their first day under the cruel communist yoke.

Whenever the citizens of Shkodra would need to refer to this event, they, not condemning the pronunciation of that name, as the most untrue thing that was for them, would ask to replace it with an equivalent of it, introducing into use groups of words, which, as the case may be, would be, like: “When they were killed”, instead of saying; “on the day of liberation”, or; “After they were killed”, or or; “almost without them”, speaking about the times “before” and “after” the liberation, where the accented pronoun diffor with strong disdainful and contemptuous semantics is omitted, for the events and people of the hated communist government, as the permanent causes of their misfortune.

Years and decades would pass, and the imposed words “friend” and “friends”, which as we mentioned a little earlier, except for rare official occasions, would not be used by the citizens of Shkodra, as they were considered hypocritical and unethical in their behavior, while, as perhaps in no other place in Albania, even after almost fifty years of communist regime, the words “lady” and “sir”, would be heard being used with delicacy, not only among people you know, but also in shops, buses, streets and everywhere, even among strangers.

Even the case of becoming a communist would be taken as a challenge to the entire civic opinion, which was also proven by the fact that the person who “with” or “without grace” had become a communist, would seek to hide his new “identity” from others, from which he would be singled out for bad luck and, himself, would feel ashamed. There have been several cases when a person was asked to become a communist, and he and his family were then involved in an unforeseen ordeal and a dilemma that was extremely difficult to resolve: To be recruited as a communist would mean to defy a conservative Shkodra, with its strict moral demands, just as, on the other hand, to reject the “invitation” to become a communist would be to later accept the consequences of such a dangerous and vengeful regime, as the communist one was.

Usually, the suggestions that in such a case would be given by the family, by some relative of the house or by a friend of the person called to become a communist, would initially be those of withdrawal, possibly without consequences, which would mostly consist of unbelievable and banal pretexts, such as “health complaints”, “unbearable family burdens”, “old and sick parents”, “bad economic situation”, etc., etc., and would often end in idiotic and hypocritical statements such as “…I’m very sorry, but I have no chance, because if I give you the word, then there will be no family and nothing else for me”.

I mean, for example a case, when a family, after several days of great anxiety, and perhaps even sleepless nights, about a son who was being asked to become a communist, finally, having failed to break the insistence of the “dark” man of the Party with various justifications, one day the father, overcome with joy both as a man and as a parent, addressed his son with these words: “We have nothing to do, accept it just once, and be careful that no one notices it”!

On another occasion, we would all be surprised to hear that a boy from my neighborhood – who had been distinguished for his gentle and calm nature, as well as exemplary in his studies – had become a communist, his father, a “guild” man, who was having difficulty raising many children at once, had been so disappointed that in a conversation with my father, with whom he was friends, he would on that occasion unleash his most serious curse possible as a parent on his son: “Don’t let him have it,” even though he might have had his first child and just as he had loved him.

To avoid prolonging it, I will tell you another case, that of a childhood friend of mine, Hysen Raboshta, who, shortly after I had been released from prison, would speak to me like this one day: “Ahmet, you were the reason why I had to spit without becoming a communist. A few days before they arrested you, there was a lot of pressure on me to become a communist. For several days in a row, both me and my brothers were very shocked by that thing. If I opposed them, I was afraid that they would remove me from my job, at a time when the living conditions in our house were miserable, but I tried to dodge with words.

When later, after a few rather difficult days for me, it happened that you were arrested, and my brother and I were finally saved from that great “embarrassment”: The director of the company where I worked as a warehouseman called me to the office, and asked: Did you have a friend named Ahmet Bushati? And I, taking advantage of the opportunity, could not wait to answer: ‘Yes, I once had a great friend named Ahmet Bushati, although I was a little older than him, because even during the War, he was the one who had gathered us in our neighborhood.’ So, I deliberately did not deny my friendship with you, and from then on they took my necks and I kept quiet!

The stance against the communist regime of the citizens of Shkodra would be consistent from the beginning of the dictatorship until its last “tornadoes”. He, as their inner voice, would find his expression of opposition in the most diverse means and ways, including jokes, the famous Shkodra jokes, which would often turn out to be “true gems” for their concise and refined construction, as well as for a thin veneer of allegory, under which all that irony and humor was disguised, which would mock and whistle that regime that had so blackened everyone’s lives.

New jokes from Shkodra would be passed on quickly, “by word of mouth and ear to ear,” from one person to another, so much so that within three or four days, they would be learned by the entire city. It would happen that a friend or acquaintance would hear a new joke, and then, even though he could see you in the middle of the square with others, seriously pointing your index finger at him, he would separate from them, and as soon as you approached him, he would address you as if seriously: “Do you want to tell me one?”

And finally, as soon as you finished telling the joke, under its provocative and irresistible effect, they would separate, laughing loudly, as if it were a joke that no one needed to be told. In my case, one of the “suppliers of such news, who was sometimes also their author, was the retired former mathematics professor, Taho Shkreli. Memorie.al