Part Two

– What did the Turkish journalist of ‘National Geographic’ Mehmet Biber see and photograph in the isolated Albania of 1980…?! –

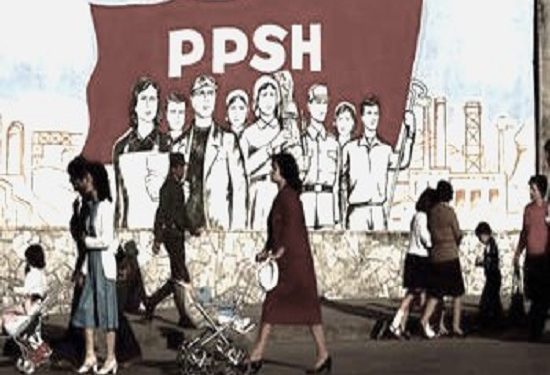

Memorie.al / ‘National Geographic’, in its October 1980 issue, carried out a reportage in Albania isolated from the communist regime. A full 36 years later, this article by the Turkish journalist, Mehmet Biber, reveals curiosities that have begun to be covered by the dust of the years…! “Let us accomplish all the tasks and destroy the blockade”, dictates this sign in the Albanian city of Shkodra, but Albania’s isolation from the world is the result of internal politics. Without allies and surrounded by nations that have had historical annexationist intentions towards its land, Albania is mobilized to walk alone under the strict dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, who has held power for 36 years. The symbols of the pickaxe and the rifle dominate the public scenes. A dogmatic Marxist-Leninist, Hoxha broke off relations with the Soviet Union, which he considered “revisionist,” in 1961, and severed ties with the People’s Republic of China two years earlier. The path to self-sufficiency is often a difficult one.

– “Marxism-Leninism is the basic subject in all faculties, leading to the ‘ideological formation’ of students. Core courses include the history of the Albanian Party of Labor, the economic policies of capitalism and socialism, dialectical materialism, ‘revisionist’ philosophy – and of course, the works of Enver Hoxha. The five-year plan sets university quotas, with quotas according to region and family profession – one-third for each: workers, farmers and intellectuals. Those whose families were landowners or merchants in the previous system have it harder.”

– “What if students don’t take the exams?”

– “Our youth are idealistic. At the end of the year, 96% pass. Those who stay are transferred to a farm or a factory. Remember, our 5-year plan determines how many doctors, engineers, geologists, scientists and teachers the country needs each year. This university cannot produce less. We must have the best young people to achieve our objectives in accordance with the plan.”

Working for the state…!

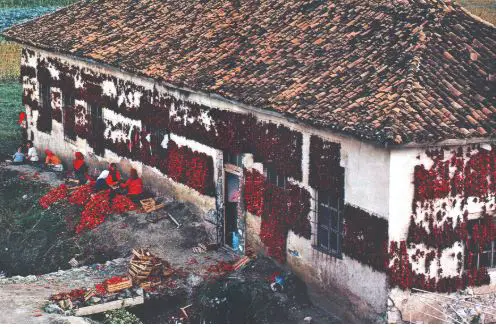

“The plan.” The phrase seemed to inspire a fear mixed with reverence whenever it was used. Indeed, in an economy as dogmatically centralized as Albania’s, the plan is sacred. The plan is based on the total nationalization of property. Every shop, restaurant and kiosk belongs to the state. Every taxi driver, barber, waiter, baker and artist works for the state. Farmers work either on state-run farms or in state-sanctioned cooperatives. Coming from an inflation-plagued Turkey, I found some aspects of Albania’s economy undeniably appealing. No income taxes. No inflation. No dependence on foreign energy sources. And since everything is tightly controlled by the state, there are no price hikes – or wage increases.

Factory workers and farmers typically earn 600 to 700 lek per month (one dollar equals 5 lek); a university professor about 1,000. Wage leveling sets a ceiling of 1,200 lek, except for high-ranking officials. By Western standards, salaries are low. But so are many of the prices. In stores, I found meat for 12 to 18 lek per kilogram ($1.10 to $1.60 a pound), bread for 2 lek (18¢ a pound); a pack of domestic cigarettes costs 2 lek (40¢).

Clothing is the biggest drain on the family budget. I have seen men’s suits made in Albania that cost a month’s salary, which I would not want to buy. Shoes are 100 lek, shirts 50 lek – but the quality is poor. The plan limits $250 million in imports, mainly in basic machinery, spare parts and raw materials, balanced by exports.

Albania keeps rents low – usually no more than 5% of household income. But officials admit there is a shortage of apartments, especially for newlyweds. Health services and education are free, and Albanians pay little for transport or entertainment. Tirana also offers few entertainment options: a few theaters showing ideological films, plays, operas and folklore programs, but no nightclubs, which reek of bourgeois decadence. Tirana has more restaurants than other cities, but few can afford to eat out often. Albanians have their own strong grape drink, raki, as well as cognac, wine and beer. But they are not drinkers. In Tirana a guy might take his girlfriend to a park, weather permitting, or to see a film on his favorite subject, the Antifascist National Liberation War.

Sami Kohen, at a factory-organized ball in the Palace of Culture. Young couples stood frozen, dancing old foxtrots and tangos, to an amateur orchestra. Discipline and calm reigned. In effect, Albania’s “cultural revolution” set the rules for youth behavior and appearance. Not just long hair and miniskirts, but also jeans, tight pants and make-up, are taboo. No drugs, premarital sex, vulgar jokes or chewing gum. Rock and jazz music with strong rhythms are not looked upon favorably. Foreign visitors usually spend their nights in the bar, tavern and restaurant of the Hotel “Dajti”, where the cuisine is relatively good. “Apart from embassy parties, there is hardly anywhere else to go, anything to do or anyone to talk to,” lamented a young Western diplomat whose previous post was in Paris.

I turned this into an opportunity to learn more about the roots of Albania’s distrust of the outside world. “If I were Albanian, I would be suspicious too,” my informant began. “Constantly, predatory neighbors have invaded: Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece, taking large chunks of Albanian territory. Consider, 1.5 million Albanians live in Yugoslavia today, half the number of Albanians in Albania. For 70 years, Greece had claims to Northern Epirus, which is southern Albania. While Western diplomats vetoed it, Mussolini marched in and occupied the entire country in 1939. Later, Tito wanted to make Albania a republic of seven Yugoslavs. Such a history left deep scars”!

Albania today has no diplomatic relations with the United States, Britain, or West Germany. Will this policy change now that Albania has severed relations with the Soviet Union and China? “The United States is an anti-imperialist superpower, just as threatening to us as social-imperialist Russia and revisionist China,” a senior Albanian Foreign Ministry official told Sami Cohen. “The Americans tried to get closer to us after the break with China, but we don’t want to deal with them.” “Britain still holds $40 million in Albanian gold, taken after World War II,” a journalist complained. “Germany refuses to pay us reparations for the Nazi occupation, which amount to $4.5 billion. We will never accept diplomatic relations with any of the countries without paying”!

Let’s move towards the future!

Today’s Albania is projected in the image of Enver Hoxha, now in his 70s. What after him? With the editor of “Hosten,” a humorous magazine, I recalled the changes in the Soviet Union after Stalin and China after Mao. Was there any chance that Albania could soften up after Enver Hoxha? – “You are comparing us to those revisionist countries”? – he reprimanded, all earnest. – “No, nothing will change after Comrade Enver passes away. The party and the nation are closely linked. His teachings give us our direction. We will not deviate from it.”

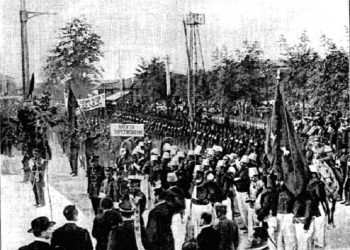

Instead of opening up to the world, self-isolated Albania always stands ready for war. In addition to two years of military service for young men, all able-bodied citizens, regardless of their profession, must serve a month or more in the armed forces. Frequent military exercises in all factories, farms, and offices prepare the people against attacks.

Everywhere I traveled – on the coast, on mountain paths, in fields, in city parks, between apartment blocks – I saw bunkers, their popular name. They look – and appear – like mushrooms. “More concrete and steel goes into bunkers than into shelters,” a diplomat told me. I knew that Enver Hoxha worried about the future of Yugoslavia after Tito—and the nightmare of a Soviet invasion. Does Albania really feel threatened? “We must prepare for the worst,” an Albanian journalist told me.

“But can tiny Albania withstand an attack by a great power”? Albania’s armaments, mostly made in China, are outdated, and diplomatic observers in Tirana say the country may look to Europe for weapons. “Even if the enemy is numerically superior, we can stop them. The entire population will mobilize in an instant. Our mountains and rivers make Albania a natural fortress. Any attack would cost the invaders dearly.” I thought of the stone houses of Gjirokastër and other mountain towns, windowless walls below and turrets above – every house a fortress, the legacy of centuries of blood feuds. And I remembered the 15th-century fortress at Krujë – the stronghold from which Skanderbeg led a 25-year war against the Ottomans.

Born Gjergj Kastrioti, and sent as a hostage at a young age to the Sultan’s court, he rose to high command in the Ottoman Empire. Named after Alexander the Great (Iskander Bey, in Turkish) whom the Turks admired, Skanderbeg defected and led 300 Albanian knights to reclaim his heritage. He abandoned Islam and stemmed the Turkish tide in Europe until his death in 1468.

He was held up as a symbol of resistance. And it was under the flag of Skanderbeg – the proud two-headed black eagle on a blood-red field – that Enver Hoxha’s partisans advanced into today’s independent Albania.

State Bans “Opium of the People”

Rain bathed Lake Skadar and blanketed the rugged Northern Albanian Alps, which guard the border with the Yugoslav Republic of Montenegro. Across the mouth of the lake, which is navigable to the Adriatic, lies Shkodra, the ancient capital of Illyria. Above it, a medieval fortress brings to mind the Venetian lords. A monument in a park there honors five Albanian partisans who sacrificed themselves while repelling 300 Nazi invaders. Nearby, I was taken to visit the Shkodra Museum of Atheism. Under Marx’s slogan; “Religion is the opium of the people” – the director, a cold man in gray, with a harsh voice, told me that religion had hindered Albania’s independence.

Because the Turks identified nationality with religion, Muslim Albanians (about 70% of the population) were considered Turks. Orthodox Christians (about 20%) were called Greeks, and Roman Catholics (about 10%) were called Latins. Services were therefore conducted, not in Albanian, which was banned and did not even have its own Roman alphabet until 1908, but in three foreign languages: Arabic, Greek, and Latin. “During the efforts to build our Albanian nation,” he continued, as he showed me exhibits on clerical abuses, “the churches served as a fifth column for fascism, imperialism, and counterrevolution.”

Hoxha’s regime executed the clergy, sentenced them to labor camps, or assigned them to “productive work.” Other communist countries keep religion in check; Albania bans it, declaring itself “the world’s first atheist state” in 1967. All 2,169 mosques, churches, monasteries and other places of “obscurantism and mysticism” have been closed, demolished or converted into recreation centers, clinics, warehouses or stables. The great cathedral of Shkodra resounds with the screams of 2,000 basketball fans. The new generation of Albanians knows only atheism. Marxist-Leninist faith replaces religious faith. Enver Hoxha’s books, published piecemeal in newspapers, quoted on the radio, selected slogans serve as a New Testament. Hoxha is held up as a messiah – infinitely wise, far-sighted and benevolent, but also implacable towards his enemies.

Raising the Leader’s Profile

Living apart from his people in a well-guarded compound on Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard, and driving a curtained Mercedes, Enver Hoxha is omnipresent. His portrait can be seen from every wall, even from trucks and tractors. His name is carved into the hillsides in letters dozens of meters high. His birthplace – a two-story stone house in Gjirokastër – is a place of national worship.

A master of Stalinist self-preservation, Hoxha ruthlessly annihilated every opponent in the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania. The revolutionary elite, convinced that human nature can be shaped by continuous indoctrination, has decided to create a new Albanian citizen who will undoubtedly make every sacrifice in his country’s fight against the “vicious imperialist-revisionist siege,” in order to build a society free from the heresy of individualism, independent thought, or foreign morality.

While trying to reshape its citizens, this small, once backward country has risen impressively on its own. Consider the great metallurgical combine in Elbasan, called “Party Steel”; the hydroelectric station in Fierzë, christened “Party Light”; a student enrollment of 700,000 compared to 56,000 in 1938; the increase from two radio transmitters in 1945 to 52 within two decades; the average life expectancy nearly doubling in four decades—all notable achievements.

The regime is also trying to dismantle the patriarchal clan structure that has made social life possible in the wild mountains of Albania. In doing so, it is quelling the vendettas that, by 1920, claimed the lives of 1 in 4 men. It has also banned blood feuds for adultery. (Mountain tradition gave a man the right to kill his wife and her lover. Her family, in a ritual of approval, would give him a bullet!)

State Bans “Opium of the People”

Rain bathed Lake Skadar and blanketed the rugged Northern Albanian Alps, which guard the border with the Yugoslav Republic of Montenegro. Across the mouth of the lake, which is navigable to the Adriatic, lies Shkodra, the ancient capital of Illyria. Above it, a medieval fortress brings to mind the Venetian lords. A monument in a park there honors five Albanian partisans who sacrificed themselves while repelling 300 Nazi invaders. Nearby, I was taken to visit the Shkodra Museum of Atheism. Under Marx’s slogan; “Religion is the opium of the people” – the director, a cold man in gray, with a harsh voice, told me that religion had hindered Albania’s independence.

Because the Turks identified nationality with religion, Muslim Albanians (about 70% of the population) were considered Turks. Orthodox Christians (about 20%) were called Greeks, and Roman Catholics (about 10%) were called Latins. Services were therefore conducted, not in Albanian, which was banned and did not even have its own Roman alphabet until 1908, but in three foreign languages: Arabic, Greek, and Latin. “During the efforts to build our Albanian nation,” he continued, as he showed me exhibits on clerical abuses, “the churches served as a fifth column for fascism, imperialism, and counterrevolution.”

Hoxha’s regime executed the clergy, sentenced them to labor camps, or assigned them to “productive work.” Other communist countries keep religion in check; Albania bans it, declaring itself “the world’s first atheist state” in 1967. All 2,169 mosques, churches, monasteries and other places of “obscurantism and mysticism” have been closed, demolished or converted into recreation centers, clinics, warehouses or stables. The great cathedral of Shkodra resounds with the screams of 2,000 basketball fans. The new generation of Albanians knows only atheism. Marxist-Leninist faith replaces religious faith. Enver Hoxha’s books, published piecemeal in newspapers, quoted on the radio, selected slogans serve as a New Testament. Hoxha is held up as a messiah – infinitely wise, far-sighted and benevolent, but also implacable towards his enemies.

Raising the Leader’s Profile

Living apart from his people in a well-guarded compound on Dëshmorët e Kombit Boulevard, and driving a curtained Mercedes, Enver Hoxha is omnipresent. His portrait can be seen from every wall, even from trucks and tractors. His name is carved into the hillsides in letters dozens of meters high. His birthplace – a two-story stone house in Gjirokastër – is a place of national worship.

A master of Stalinist self-preservation, Hoxha ruthlessly annihilated every opponent in the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania. The revolutionary elite, convinced that human nature can be shaped by continuous indoctrination, has decided to create a new Albanian citizen who will undoubtedly make every sacrifice in his country’s fight against the “vicious imperialist-revisionist siege,” in order to build a society free from the heresy of individualism, independent thought, or foreign morality.

While trying to reshape its citizens, this small, once backward country has risen impressively on its own. Consider the great metallurgical combine in Elbasan, called “Party Steel”; the hydroelectric station in Fierzë, christened “Party Light”; a student enrollment of 700,000 compared to 56,000 in 1938; the increase from two radio transmitters in 1945 to 52 within two decades; the average life expectancy nearly doubling in four decades—all notable achievements.

The regime is also trying to dismantle the patriarchal clan structure that has made social life possible in the wild mountains of Albania. In doing so, it is quelling the vendettas that, by 1920, claimed the lives of 1 in 4 men. It has also banned blood feuds for adultery. (Mountain tradition gave a man the right to kill his wife and her lover. Her family, in a ritual of approval, would give him a bullet!)

The reformers put an end to cradle marriages and the sale of 12-year-old brides; they attacked customs that kept the Albanian woman, traditionally considered “long-haired and short-witted,” in an inferior position. No corner of Albanian life, material or spiritual, escaped Hoxha’s impulse for control. People with names that were “inappropriate or offensive,” politically, ideologically, or morally, had to change them. Even the dead were not spared by Hoxha’s reforming zeal. Burials, paid for by the state, took place on communal lands, without traditional religious divisions.

If you turn the bright side of the coin of the increase in “literacy” (as they used to say) the dark side of the increase in thought control appears, as the Directorate of Agitation and Propaganda determines what Albanians will read, just as the state decides who will work where, who will be rewarded and who will be punished.

The suspicious society closes its doors. The harsh hand of history has fixed suspicion in the Albanian psyche. After three weeks in Albania, I realized how little I had managed to penetrate the facade of this ominous social experiment. Never in my travels around the world had I encountered such a closed society, never had I felt so much on an island. Accompanied and watched at all times, I felt that the distinctive yellow car in which I traveled was like a bell announcing the approach of a medieval leper.

My guide, Bashkim Babani, stood behind me to see what my camera was recording. He allowed me to take pictures outside industrial plants, but not to observe them at work, to visit a hydroelectric dam, but not the power plant. At a distillery, I was given raki to drink, but I couldn’t see how it was made. Requests to visit families and homes were politely avoided, or ignored. No photos of bunkers, donkeys, anything primitive, of course. But Bashkim also forbade me from reproducing images from Albanian postcards. One citizen objected to taking pictures of children in front of the Tirana Puppet Theater. Bashkim discouraged me from taking pictures during a wedding ceremony. The regime downplays such traditional celebrations. I don’t even remember seeing a domestic dog or cat, bourgeois luxuries.

I once struck up a direct conversation with a villager in Turkish. Bashkimi immediately turned the conversation back to Albanian and translated the answers into the usual party jargon. I couldn’t even break his defense. He was correct and cordial, as most Albanians were. Only once did I encounter a breach of hospitality – a teenager on a collective grape farm near Shkodra spat at my feet and let out a slogan; “down with foreigners”. I tried to break the barriers, telling Bashkimi about my life in Istanbul, with my wife and son. But he never opened the curtain, as in Enver Hoxha’s “Mercedes”, to allow me a glimpse into his private life and thoughts. Indeed, he seemed to embody the same demeanor, the same mask, that his country wears so defiantly. Memorie.al