Part One

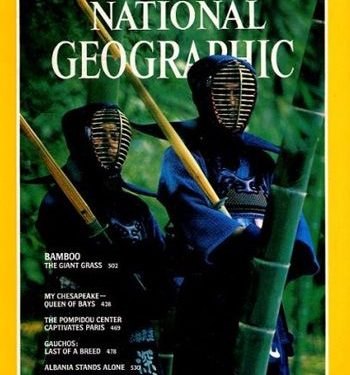

– What did the Turkish journalist of ‘National Geographic’ Mehmet Biber see and photograph in the isolated Albania of 1980…?! –

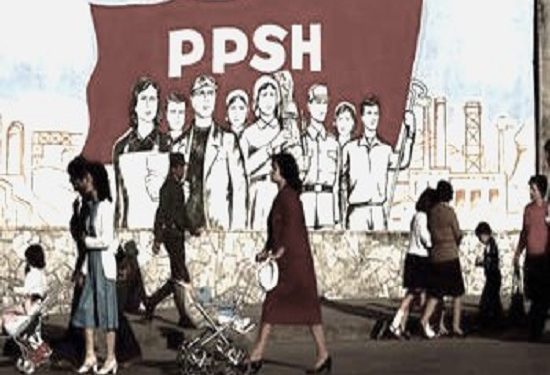

Memorie.al/ ‘National Geographic’, in its October 1980 issue, carried out a reportage in Albania isolated from the communist regime. A full 36 years later, this article by the Turkish journalist, Mehmet Biber, reveals curiosities that have begun to be covered by the dust of the years…! “Let us accomplish all the tasks and break the blockade”, dictates this sign in the Albanian city of Shkodra, but Albania’s isolation from the world is the result of internal politics. Without allies and surrounded by nations that have had historical annexationist intentions towards its land, Albania is mobilized to walk alone under the strict dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, who has held power for 36 years. The symbols of the pickaxe and the rifle dominate the public scenes.A dogmatic Marxist-Leninist, Hoxha broke off relations with the Soviet Union, which he considered “revisionist,” in 1961, and severed ties with the People’s Republic of China two years earlier. The path to self-sufficiency is often a difficult one.

Private cars are banned, so Albanians travel by bicycle. Visits by journalists are rare. Last year, Mehmet Biber, a Turkish photographer living in Istanbul at the time, obtained a visa just months after journalist Sami Cohen, another Istanbul resident, had visited the country. From conversations with Mr. Cohen and his own experiences, Mr. Biber brought the first full report from Albania to appear in an American magazine in many years.

The plane flew south from Yugoslavia over the cobalt-colored Adriatic, turned 90 degrees, and headed overland toward Albania. In ancient times, Roman legions descending the Appian Way to Brindisi, at the heel of Italy, and crossing the Strait of Otranto arrived here and marched east on the great military route to Salonika and Constantinople. The Goths and Normans conquered them. The Byzantine, Bulgarian, Serbian, and Venetian empires helped them. After that, the Ottoman Turks ruled for almost five centuries, making Albania the only Muslim-majority country in Europe. Then came the armies of Mussolini and Hitler.

Today, no international highway passes through Albania. Its 300 kilometers (185 miles) of railways cross no borders. No foreign aircraft are allowed to fly into its airspace. Commercial flights, like our biweekly semi-suburban flight from Belgrade, must pass by sea and only during daylight hours.

I looked around the cabin at my twenty-something fellow travelers: an elderly woman, a diplomat, an Austrian professor of Albanian (with little contact with other European languages), and businessmen who came to buy minerals or sell machinery. How did I fit into the visitor guidelines set by Albania’s dictator, the head of the Communist Party, Enver Hoxha? He had declared his country “closed to enemies, spies, hippies and hooligans, but open to friends (Marxists or non-Marxists), revolutionaries and progressive democrats, to honest tourists… who do not interfere in our affairs.”

More apt was the comment of a travel agent: “Only madmen, diplomats and journalists go to Albania.” I was a Turkish journalist and had waited almost a year for my visa application to be approved. We passed over the beach and coastal plain near Durrës and saw, beyond the terraced hills, a jagged line of misty peaks running across the horizon, like a giant electrocardiogram.

I wondered what I would find in this tiny nation of 2.7 million people, about the size of Maryland, with fewer inhabitants, and as little known as Tibet! For millennia, the descendants of ancient tribes known as the Illyrians have clung to the harshest terrain in the Balkans (which translates to ‘mountains’ in Turkish). Amidst peaks rising to 2,764 meters (9,068 feet), they followed a strict clan code of honor that wiped out entire families through blood feuds that spanned generations.

Today this “Land of Eagles” is completely collectivized. The last stronghold of Stalinism, this is Europe’s most dogmatic communist country, gripped in the grip of a leader who has transformed the continent’s most backward nation from the ashes of World War II into a driving force toward modernization, from the plow to the tractor, from the handicraft and the lamp, to factories and dynamos.

Here I would find an unusual social experiment: an entire generation growing up locked in a secluded socialist laboratory, defying the world, self-isolated, “uncontaminated” by East or West. I unconsciously rubbed my beard, and was frightened by the sudden realization that I might lose it! Albania forbids entry to men with long hair or beards, and women in short skirts, baggy pants, and other displays of bourgeois decadence. Stories abound of unfortunate visitors being whisked away to the airport barber for a haircut.

But the soldier who met me at the plane door was more intent on my passport than my beard, and I landed in the afternoon sun of a September day, at one of Europe’s smallest and sleepiest airports, shaded by palm trees and fruit-laden orange groves. Kopi Kyçyky greeted me in Turkish. A member of the Foreign Ministry’s welcoming committee, he brought my daily itinerary to my guide-translator every morning. Now he brought me express, expedited formalities, and escorted me to a Polish Fiat for the 30-minute drive to Tirana, the country’s capital. Along the way, brigades of peasants stopped to work in the fields. But we encountered little traffic on the roads.

Traffic cop without traffic

Life in Tirana revolves around Skanderbeg Square, with its monument to the 15th-century hero who fought against the Ottoman Empire. The modern Palace of Culture overlooks it, as do several royal buildings of King Zog, who ruled in the late 1920s and 1930s. One of them now serves as the offices of the satirical magazine Hosteni; another, the old Parliament building, has been converted into a puppet theater for children.

A kilometer from Skanderbeg Square, in University Square, lies the Boulevard of the Martyrs of the Nation, flanked by giant statues of Lenin and Stalin, the general headquarters of the Communist Party, the main ministries, and the football stadium. In the early morning, the square seems deserted: an official car, a military vehicle, a bus, a few bicycles, a few elderly women wandering the streets. Still, in the center of the square, a policeman stood solemnly directing traffic.

Albania does not allow private cars, and its capital has only 20 taxis, all state-owned. Most were lined up near the square. Albanians rarely use them. We stopped in front of the Hotel “Dajti,” built by the Italians in the early 1940s, when the street was called “Viale Savoia.” It is one of two hotels in Tirana for foreigners, and locals cannot stay there.

My room with a balcony was decorated with a beautiful carpet. Downstairs in the gift shop, such a carpet sells for $20 per square meter, in foreign currency. I checked the TV room—only local programs could be broadcast. I studied the press publications spread out on a table in the large lobby and stopped in front of a display of publications: the magazine “Shqipëria e Re”; “Zëri i Popullit,” (the party newspaper); and a selection of Albanian dailies, all similar in content. Editions of Enver Hoxha’s books available in several languages—but no foreign newspapers, magazines, or books. It was as if the outside world did not exist.

Leaving the hotel at dusk, I returned to “Skënderbej” Square. What a change! It seemed as if half of Tirana’s 200,000 residents had gathered there after work. Some strolled along the promenades along Stalin Boulevard, others chatted in small groups or gathered around kiosks to buy Albanian cigarettes, soft drinks and newspapers. Young men and women flirted. Parents poured into the Palace of Culture for a concert, show or exhibition, while students flocked to the National Library. And amidst the chaos of buses, bicycles and pedestrians in the square, a policeman strictly supervised the traffic with his whistle. For about two hours, the heart of Tirana pulsed with life, then fell silent again. Even the traffic policeman had gone home.

The Nation Kicks the “Revisionist” Giants

The next morning Bashkim Babani, my guide-translator, a thin man in his mid-thirties, took me to the Palace of Culture. Albanians are proud of this building, begun by the Russians and left unfinished when they left Albania in 1961, as a result of an ideological split. My guide said: “The Soviet revisionists and imperialists cut off all aid to us and imposed an economic blockade on us, thinking that we would soon be destroyed. But we mobilized our forces and completed this building. Today it stands as a symbol of our triumph.”

After breaking with the “traitors of the Khrushchev group,” Hoxha turned to the Soviet Union’s opponent, Mao Zedong’s China. Albania became China’s closest friend, its supporter in the United Nations, and received between one and two billion dollars in economic and military aid. This lasted until 1978, when China’s restoration of friendly relations with the “imperialist” United States and “revisionist” Yugoslavia brought about the breakdown of “eternal friendship.” Claiming to be able to smell “the infidelity… of those who kill at night and cry during the day” in the “hypocritical smiles” of Mao’s followers, Albania now remained the only stronghold of “true Marxism-Leninism.”

Where would Albania turn this time?

From Tirana to the smallest village, on the streets, on buildings, in factories, schools and farms, slogans proclaimed the answer.

A banner in Skanderbeg Square read: “Without any help and without any loans from abroad, let us rely entirely on our own strength.” Over the old town hall: “Let us break the blockade and siege of imperialism and revisionism.” Over the Prime Minister’s office: “Long live popular power.” A foreign language class studies Hoxha’s slogan on the blackboard in English: “Let us build socialism, with the pickaxe in one hand and the rifle in the other.” Defying the world – seeing itself against giant China and threatened by the USSR and its Eastern Bloc satellites; fearful and suspicious of Yugoslavia and neighboring Greece and the West – Lilliputian Albania will go it alone.

How can I do this?

By mobilizing production. Factories often work three shifts, so that they can use their machines 24 hours a day. I saw tractors plowing fields with headlights, and then driving trucks at night to another agricultural cooperative for the morning plowing. As part of this ‘technical revolution’, some engineers, technicians, and workers are adding a few hours to their 8-hour day. “Do you get paid for the extra hours?” The question was asked to a worker in a Tirana factory that produces spare parts for trucks and tractors.

“No, we don’t ask for that. We do volunteer work because we believe that this work is the way to break the blockade. This revolutionary spirit will lead us to victory”! Mark Toma retired three years ago, at the age of 60. But now he is back at the same factory.

“We are united under this goal, to contribute to making our economy self-sufficient. I am still strong. I cannot sit idly by while the whole nation fights.” Was he getting paid?

“I already receive my pension”!

Civil servants, students, even party officials and diplomats, worked at least a month a year, in factories or farms.

Brigades of workers compete to exceed production quotas. This brings rewards in the form of medals and extra days of vacation at a rest camp. Noticeboards are full of leaflets, with the aim of improving morale and productivity through ‘self-criticism’. At the “Enver Hoxha” Factory in Tirana, my colleague, Sami Kohen, was proudly shown the first tractor made in Albania. When the Chinese cut off aid, they left this factory, a hydroelectric dam, mines and other large projects unfinished.

“The Chinese technicians even took all the plans,” said the angry director. “Then they tried to sabotage the factory, refusing to bring the necessary parts of the machinery. But we finished the factory and got the machinery and parts from other countries. Not as foreign aid, or as loans. We had enough of this help from the Russians and the Chinese. If we need something, we buy it from another country – with money. Or we exchange it. In this way, we maintain our independence.” In fact, the Albanian Constitution of 1976 prohibits credit agreements, not allowing bank loans from the East or the West.

Living Well, Albanian

Few other countries would have chosen this difficult path to development. But Albania is ruled with an iron fist. And Albanians are accustomed to deprivation. The hardships of earthquakes and floods followed the horrors of war. When the Russians withdrew, severe droughts raised the specter of starvation; many amenities were curtailed. Today, although Albania is far from prosperous, there are no severe shortages or rationing.

People are simply dressed, but no one is in rags. Families live in small apartments or houses, poorly furnished by Western standards. But compared to yesterday’s misery, Albanians have no doubt that they are better off today. And they pride themselves on their will to survive on their own terms: “We prefer to eat grass, if we have to. We will never extend a hand to the imperialists.”

“We have experienced difficult days,” 71-year-old Kristo Teodori told Sami Cohen during a visit to a cooperative in Finiq, southern Albania. “I spent my youth in misery, in these fields. I worked hard for the landowner, but I barely managed to earn enough to live. Today, thanks to Enver Hoxha, we live well.” The old man shares a three-room house with his son, Jorgo, 47, his daughter-in-law and her sister. Sipping Turkish coffee and cognac, he said; “The cooperative today includes 17 villages with 8,000 inhabitants and 3,400 hectares of land, which produces wheat, corn, rice, cotton, vegetables, fruit, pigs and cows. Before the “liberation”, this was 80% swampland.

The land belongs to the state; the houses, tools and seeds all belong to the cooperative, and each farmer receives a share of the production. Sales of surpluses help to maintain a medical center, schools, shops, a theater and sports facilities. The three working family members earn enough for the basics, so Kristo Teodori can spend part of his 420 lek (85 dollars) pension on cognac and cigarettes. “I call it the ‘Enver Hoxha Bonus’”.

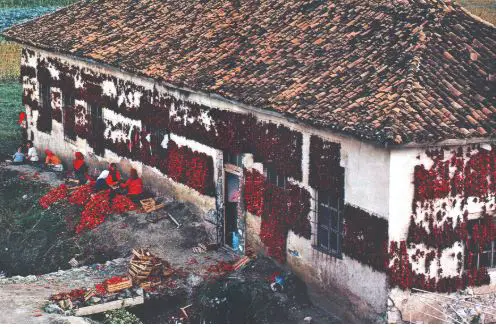

Hoxha’s regime announced agrarian reform in 1945, taking land from landowners and distributing it to the peasants. Collectivization was was completed in 1960. The results: drained, flood-controlled valleys, irrigated farms, and terraced hillsides. The arable land of mountainous Albania, once a meager 10 percent, has doubled, malaria has been eradicated, and health and social services have improved dramatically. Four decades ago, Albanians could expect to live to be 38. Today, their life expectancy has increased to 68.

In its challenge to the world, Albania can also rely on its mineral and energy resources. After South Africa and the Soviet Union, Albania ranks third in the production of chromium. Limited in needs, it is self-sufficient in energy – oil, coal, and abundant hydroelectric power from river dams. I saw power lines, all over the country. Mountain villages have been electrified, and Albania even sells surplus energy to neighboring Yugoslavia and Greece.

Industrial, mineral, and agricultural products fill the “Albania Today” exhibition in Tirana. “Everything here is the product of our work and sacrifice,” says Hysen Vaqarri, the exhibition’s director. “We even produce enough food for export. Not even the global energy crisis affects us. We produce everything from radios to kitchen utensils. We do it all with our own strength – without external support”!

They are so determined to support themselves that Albania shunned aid from the International Red Cross when an earthquake devastated the Shkodra region in northern Albania in April 1979. All across Albania, I saw students, men and women, building roads, houses, working in the fields, and in factories. Albania’s railway system is being extended northward, mainly through student labor. “This physical labor allows us students to get to know our country and people better, to increase our practical knowledge, to share our theoretical education, and allows us to build socialism”!

Thus said Gjergj Murra, Bashkim Çami, Zeliha Kraja, history students at the State University of Tirana. In addition to six hours of classes a day, they also do one full day of military training a week.

– “What do you do after school?”

– “We study the day’s lessons.”

– “And in your free time?”

– “We go for a walk… go to the theater or the cinema… listen to classical music.”

The courses last eight months. Then, in addition to the month of physical labor for students, there is a month of military service, for girls as well as for boys. All high school graduates must serve a year on a farm or factory before starting work or entering university.

“And after graduation?” “A year of internship before starting work. A medical graduate serves in a hospital. An engineer in a factory. Graduates in philosophy or linguistics usually teach. University administrators say that 80% of the population was illiterate in 1938; today 80% can read and write. The university began in 1957 with 3,600 students. Today there are 16,000 enrolled in seven faculties: engineering, political science, geology, history, economics, medicine, and natural sciences.” But no law school. Why not?

“Our system does not need lawyers,” came the reply. “Our citizens do not need a third person to defend them. The judges of the People’s Court, elected by the people, take their rights into consideration.” Ominously, the Ministry of Justice disappeared in one of Enver Hoxha’s many administrative reforms. Memorie.al