By Arshi Pipa

Memorie.al / Behind the prison of Durrës, inside the wires is a ground floor building. It serves simultaneously as a canteen and as a school, where the policemen receive their daily meals, where they also receive party lessons. This time it also serves as a courtroom. Nanduer 1947. The prisoners’ hove-hoves are brought before the court-martial. It’s the worst wave of terror. Intellectuals, technicians, clergy, but also artisans, peasants, all those who are thought to be opponents, active or not, of the party, have been wiped out and beaten in prisons. The judgment is just for the eyes; the processes are organized before me by the Ministry of the Interior, the trial only puts them on stage. The prisoner is taken one day by the Security Branch and put in a room. He sees in front of him, sitting at the table, three major officers, another one a little to the side, a non-commissioned officer with a typewriter.

One of them reads a sheet, usually the beginning or the end of it: the questions continue, accompanied by threats and threats. This continues for up to twenty minutes, depending on the occasion. Then the prisoner is taken out and another enters the room. The man suspects that he is in an investigation session. After they bring him to prison, he finds out that he was before the military court. For several days in a row, the military court of the Garrison of Tirana, presided over by Major Gjon Banushi, has held trials like this, with closed doors. Now is the decision.

In the small hall, about sixty prisoners are sitting on benches. Many do not know each other. Dark, pale faces, looking at each other fearfully, incredulously. Enter the jury. Prosecutor, Capt. I. Petrit Hakani, starts the claim. He makes a short, urgent summary, then pulls out a stack of papers from his bag and distributes the list of the first group. In front of me, there is a man with white hair, he gathers his collected, and he wears a black cloak that leaves ink. It hasn’t moved the whole time. Move now to call a name: Vincens Prenushi!

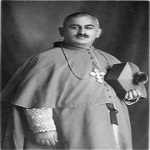

He gets up slowly, probably, and sits down without saying a word. The prosecutor reads the defendant’s claim. The accusations are completely generic, without any concrete facts, those are now stereotypes: “friend of the people”, “collaborator of the occupier”, “fascist”. The fact that he was the Bishop of the Catholic Church is emphasized, and on this occasions the phrases: “reactionary clergy”, “agent of the Vatican” is added. At the end of the sentence searches: twenty years.

Twenty years in those circumstances, and for a personality like Vinçenc Prennushi, it’s not too bad, when you think back, the prosecutor demands the death penalty for his vicar, Dom Anton Zogajn. In the last word, Monsignor Prennushi says with a sigh: “I don’t wish anyone harm. I tried to do well”.

The decision of the court is: twenty years of deprivation of liberty, with compulsory labor!

Monsignor Prennushin was announced after the trial. They shot us sitting together, in a small prison room, where they also put the Mufti of Durrës, Mustafa Varosh, Prof. Prenk Kacnarin and another professor. A few days ago, the Mufti, who was reduced to a living corpse from the terrible tortures during the investigation, died in a hospital in Durrës. Prof. Prenk Kacinari, who suffered from tuberculosis, was released from prison in 1949. Fed up with the constant persecution, he killed himself in 1956.

A few days later, we moved there to another room. I remember well this room, separate from the others, with one end of the yard; it used to be a dungeon (weapon depot) and had thick walls, a dome-shaped ceiling, and only one small window. In this room, I announce it with the name “Room no. 8”, the “most dangerous” were usually placed. We were close, about thirty of us, in a space of less than thirty square meters. Despite this, the prisoners were narrowed down, and I gave the Monsignor a similar place, I put him at the head of the room. He shot me, being near him.

It didn’t take long and we became friends. We were meeting on political matters, you commented on the situation in a low voice, so that the words could not be heard by others. The communist tortures, we had to be careful. But His Holiness did not like politics, and we often discussed other matters, literature, past matters, various personal experiences. With others, the Reverend was very restrained and opened his mouth to give me some advice, even when he was asked, or to comfort me with soft words, the suffering hearts of people.

He rarely told any events of his life, any anecdote or a historical fact, and always with an educational purpose. Then the whole room looked at him in a religious silence. He spoke simply, in a way that even the villagers could understand. She shared with the little ones, the little food that a soulful old woman would have when she had it. He would sit, sometimes for hours, in his place without speaking, looking out the window.

He was probably praying then. He was gentle with a peaceful soul, deeply pious, devoted himself to his ecclesiastical mission, in the framework of which he knew how to reconcile, with a persuasive wisdom, his love for the Motherland and his taste for literature. They smile when they speak, kind-hearted among judgments, calm and confident in their unshakable faith, but not closed to the century, even very understanding of people’s needs and shortcomings.

Monsignor Prennushi lived quickly for himself. After we got close enough, I begged him for permission to call him Father Vincenc: the title of the old Franciscan sounded dearer to my heart in those sad conditions, where the differences between people could only be of the moral order. The ecclesiastical dignity of Vinçenc Prennushi, combined with his literary value and viewed under the prism of Albanian patriotism, gives your face a major importance in the ranks of the nation’s representatives.

A SPOTLESS LIFE

His life is an unblemished life, written in the service of some of the superior human ideals, such as: Motherland, art, religion. The name of Vinçenc Prennushi is a favorite name, especially for the people of Shkodra. As a young man, dressed in the robes of Saint Francis, Pater Vinçenci showed rare tact and understanding in taming religious fanaticism in the city of Shkodra, during the turbulent times after the creation of the Albanian State. Since then, he stood out for his patriotism among the order of Saint Francis, this religious order, to whom Albania owes the greatest respect, for his great services in the field of culture and the Albanian issue in general.

One remembers the beautiful and wise patriotic lectures of the young priest among different races in relation to historical dates. In those times, the literary activity of Patër Vinçenci also began, who, in the collection and publication of “Gegënishte Folk Songs”, gave a new boost, in a more scientific direction, to Albanian folklore and with his first published lyrics temporary “Hylli i Drita” and “Zani i Shna Ndout”, you have carved a worthy name for yourself in the history of Albanian literature.

Vinçenc Prennushi was one of the most fruitful workers of our literature; in addition to his main work “Flower Leaf”, where his own poems are mentioned, he adapted or translated many works of world literature into Albanian, he is always guided in his choice by the criterion of reconciliation between art and religion. For his ability as a spiritual leader, Father Vincensi was chosen by the Provincial of the Albanian Franciscans and, later, named by the Shejte See, Ipeshkv. The Italian occupation found Monsignor Prennushin Argjipeshkev of Durrës, one of the two highest dignitaries of the Albanian Catholic Church.

As such, on the one hand, and, on the other, as some of the representatives of national literature, Mr. Prennushi could not have long with communism, which is at the same time against religion and nationality. Monsignor Prennushi, has been with me since Enver Hoxha had called him, supposedly to consult with him about the affairs of the Albanian Catholic Church, in fact to impose on him the views of communist politics towards religion. He couldn’t convince her.

Later, after Monsignor Prennushi was imprisoned, he vehemently attacked him in one of his speeches. After they imprisoned him, they tortured him. I know from his own mouth that they beat him with a stick, then they tied him by the legs and hands, they drove a stick between them with a hook in it, then they hung the stick with a big nail, on the wall of the toilet, they left it there until it happened to turn off. “Like a ram in a krabra”, Monzoti added with a smile, who did not lack a sense of humor.

THE PRELATE WAS HANGED AND STRUGGLED

Now imagine this man, a sixty-five-year-old man, a high prelate of the Church, one of the very rare writers of the Renaissance, still alive, imagine him hanging in a prison of the Security Branch. This man is regarded by the Albanians with the greatest respect, he is preserved in their gratitude as a relic inside his box, this symbol of the transition of Albania, for which we are proud, and this man is kidnapped and raped from his humble home the village, where he spent the last days of his life, together with God and with books, and is imprisoned and tortured.

One day they took him out with logs. The prison of Durres, they are placed a little on the hill and the trucks used to drive down the road: from there they loaded the prisoners, you climbed them up and you stacked them. One of the guards, when he was assigning the workers, asked the Reverend: “You too, priest”! Everyone was surprised because until that day, they didn’t bother him for such things: He was not only old, but he had, moreover, a remarkable hernia, that he barely walked. The monk did not say, duel with others.

I didn’t laugh that day at work, but my friends later told me everything. They had loaded logs on his shoulders, which he could never carry; he was rolling with them, once, twice, three times, and always without a trace. The director of the prison and the commissar shout “observes” from the stairs of the prison. They laughed. His friends did their best to help him: they let him have the lighter side of the log, when it was thin, or, when it was very thick and long, they shared the weight on their shoulders, so that the log would not fall on him weighed them down.

But even just going uphill was very, very possible. Many times he had fallen motionless, he was out of breath. The guards then let him rest for a few minutes and put him back to work. “Priest”, have you ever done work like this”!? The director of the prison once asked him, and he frowned. He, like the policemen, did not call him anything other than “priest”. They pronounced this word, with a twist of the lips, emphasized in their mind. The word was sham.

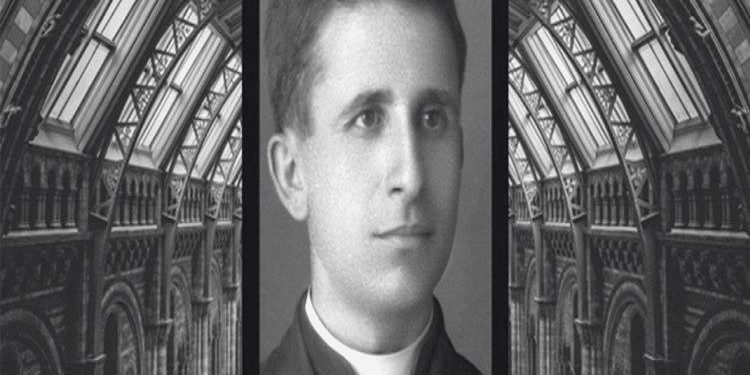

His main concern was for Dom Anton Zogajn. Dom Antoni was sentenced to death and was then locked in one of the cells that served as a bath. He had been the parish priest of Durrës, therefore, under the rightful dependence of Monsignor. It was dangerous with the possibility of the death penalty, but with the help of his friends, the Reverend was able to fulfill the vicar’s last wishes. One of these was to take out of the prison the cuffs of the religious garment, which he always wore.

I did this as long as I could, Monsieur did not know how to thank him for this. I asked the Reverend, if he had left any manuscripts at home. He replied that he had edited Weber’s translation “Dreizchlinden”. When I asked him why he had translated this work himself and not someone else who knew German literature, since he had been educated in Austria, he told me that he had chosen that work because the customs of the Austrian mountaineers had many things in common with those of our highlanders.

SICK MONSTER

I lived with Monsignor Prennus until the summer of 1948, when I was sent, together with my friends, to the labor camp of Vloçishti. When I returned there, from the end of the nandor, I found the Monsignor sick. He ate from the heart and rarely left the room to go out into the yard. His condition worsened rapidly. They send him to the hospital. A little later I also went to the hospital. The prison hospital was located at that time in a ground-floor building, an annex of the Durrës Hospital, which fell on a narrow street, not far from “Dalip Tabaku” Boulevard, built by the prisoners.

The room was small, low, and old, with two windows, which looked towards the sea. It had been a fire room before, because it had its own. The doctors had diagnosed Monzoti with a “heart defect”, a serious illness, especially for his age. Asthma constricted him more at night. He came to them in spurts as they went and accelerated to the point of heavy breathing, which left him breathless. When he passed, after a few hours, he fell as if he was dead and for a long time he could not speak to me. The doctor of the pavilion, Dr. Propopulli, a man with a heart of gold, who felt sorry for the prisoners and whom he served with his soul, did everything for the Monsignor.

He visited her several times a day, out of habit, and often dropped his own medicine, since the hospital didn’t have any. This was in February 1948. It was said then that, after the break with Yugoslavia, the government was preparing a big amnesty, from which all the innocent prisoners would benefit. In the state in which the Reverend was, the hope of getting out of prison, spending the last days of his life at home, under the care of someone he loved, was a way to keep him alive, and I tried as much as possible sing that hope.

I didn’t think at all that the communists would release him for the sake of the law, but I had a feeling that maybe the logic of the new political line could progress as the government forces them to do what they don’t want. During those days, we had many meetings with the Reverend, on the political situation, in which I went and fed him the hope of release.

A SAD SCENE

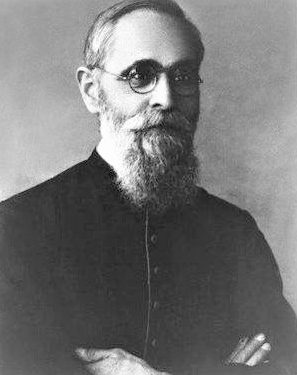

I remember a sad scene. One day, Dom Jul Bonatin, the parish priest of Vlona, came among us for a short time. They took him from the prison of Vlona, to shelter him in the asylum for the insane in Durrës. I had known Dom Jul Bonat, since I was a student in Florence; he was trying to print his own Italian translation of “Lahuta e Malcis”.

I leave the assembly. I told him that the man who was panting in bed was Monsignor Prennushi. Then Dom Bonati, who was barely supported by illness and advanced old age, got up and almost crawled over to the Monsignor: I tried to kiss his hand, but the Monsignor, despite his panting anxiety, did not let go and withdrew his hand. Then Dom Bonati asked for his blessing and the Monsignor, with a final effort, put his hand on his head. Then he sat down on the bed.

He didn’t die then, but a few days later. During those days he removed more than ever. Horror was the night. Until midnight there was electric light, until then the suffering was more bearable. But, when the light went out, in the darkness that suffocated the room, his suffering grew and grew worse. The lack of light was overwhelming, he lacked breath. Gulshim was done then, like the moaning of a wounded person, who, instead of going to the ground, came to the ground, until the growling.

It used to be, as he told me, when the irons clamped down on his chest, he squeezed his heart worse and worse, he was gone. At that time, one could not even sleep in the room. We would stand up in turn and rub his legs – that’s how it seemed that something was relieved. We kept the fire in our house unextinguished: we didn’t have a candle and the light of the flame helped a lot to ease the suffering.

Therefore, since the evening, we took care of it, gathering a lot of wood in our house. It was a sunday, the room was heated by the stove, so a quantity of wood for the fire was foreseen. But this amount was not enough to keep the fire going all night and we had to, in different ways, convince the guards to order the hospital staff to bring us as much wood as possible.

LOOKED FOR LIGHT

It was happening often, we couldn’t have enough wood. And when we turned off the last curtains and the darkness weighed in the room, we got up from the bed, sometimes one, sometimes the other, and lay down on the head, you talked (talking somehow made the work easier), you gave him heart, you lied to him that there would be other wood or, because the night was in the sauce…! One such night he told me in bits and pieces: “Now I am remembering the words of Goethe, “Mehr Licht” (I want light). That light to which the poet had called at the point of death was, of course, not the light that our sensory eyes see.

And this, the Reverend knew well. But what man did not see in the sweet light of heaven, the symbol of life? “With his eyes I saw light on the earth”, says our people, with a wildly poetic expression, to describe life. And when the man’s mind wandered to find a bridge, the passage between land and land stopped, as once and for all, but at the light. From Neoplatomism, Augustine relates, to the Franciscan school of Oxford, the image of light illuminated the concept of philosophy, the intermediary between poetry and mysticism. And Foscolo had said near our days:

“Perche gli occhi dell’uomo cercono morendo il Sole…” Monsignor Prennushi passed away one cold night in 1948. That night there was a fire in his heart. When I closed his eyes, his eyes were tired and exhausted, as they had longed for light, it seemed to me that I saw in his face, pale, written, peaceful after so much effort, an unusual illumination. Sometimes my eyes watered and teared up; maybe it was just a reflex of the red flames of your fire, hidden between the deep wrinkles of the long forehead, between the hollows of the cheeks and between the sockets of the eyes.

But maybe it was something else. The soul in the throes of physical pain melts, shrinks, shrinks, as it drains from it, when the pain is gone, like water from the mud that has disturbed it. Man may not believe in the immortality of the soul. But it is difficult to accept that everything ends with the body, when we notice that people die for ideals. Memorie.al