By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part twenty-seven

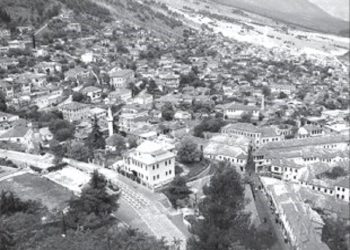

S P A Ç

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My memories and those of others)

Memorie.al /Now in my old age, I feel obliged to tell my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whose mouths the regime sealed, burying them in nameless pits. In no case do I presume to usurp the monopoly on truth or claim the laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, even though I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly deterred me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little more left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months after, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days; I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

“‘Marrok’ went out with the partisans before finishing high school,” Tomor began his narration. “After the war, he first dealt with the youth; later, he completed the State Security School in Czechoslovakia, and since he had political guarantees, he was appointed to the ranks of diplomacy with a spying assignment, tasked with observing the consular corps. But the embassy employees felt obligated to serve the counter-intelligence and zealously fulfilled their agent duties, so he didn’t have much to do.

During this period, the brain trust of the political emigration focused on France, from the Zogists led by King Zog, the leaders of the nationalist parties, and even the anti-Enver communists themselves, led by Sadik Premtja. They saw France as the state where they could develop their activity as close as possible to the homeland; consequently, they gathered in Paris, as the capital of European politics.

As I said, ‘Xhepi’ the communist and Ermenji the nationalist represented Enver’s specific adversaries, whom he attempted to fabricate accidents or assassination attempts against, in order to physically eliminate them. He sent one after the other, the most experienced cadres, but they failed. Then someone remembered ‘Marrok,’ who knew the French language and culture and was capable of penetrating different groups; furthermore, his family and social circle provided an added guarantee.

The leaders of the Ministry of Internal Affairs themselves instructed him in detail on the task he would carry out, trained him intensively, and sent him incognito to Paris. Through the agent network, they settled him in a hotel in the center of the neighborhood where the ‘object’ lived and familiarized him with the area’s layout, where he would operate; they taught him all the hangouts, the roads, the alleys ‘Xhepi’ used to pass, the apartment where he lived, the bars he frequented, and the people he associated with.

Being incognito gave him the opportunity to get to know the early emigrants, but the ‘object’ and the same circles he frequented remained his goal. But it was not easy for him to penetrate, because ‘Xhepi’ was a heavyweight exponent of the French Communist Party.

Well-informed, the spy intended to quickly conclude the mission, but the scenario was not destined to match reality. Therefore, they had to change tactics; they ‘arranged’ a mistress for him from the radical groups, through whom he managed to enter ‘Xhepi’s’ lair, even getting to know him personally. Here began the downfall.

The prolonged emigration and modest economy, the repeated threats, and the incessant alarm had turned ‘Xhepi’ into a pathological doubter, while the respect and reputation he enjoyed among ordinary communists had transformed him into an almost adored figure.

His semi-clandestine life had instilled in him the instinct of a fox; the attempts to eliminate him had sharpened his vigilance, turning him distrustful and cynical towards everyone; thus, he also doubted the new ‘friend.’ Meanwhile, the newcomer was blinded by the Parisian life; he plunged into rampant pleasures, almost forgetting the mission he had been tasked with. He lacked neither luxury, the woman in his bed, nor money, but they pushed him towards debauchery, making him forget that they might be playing a trick on him.

The influence of the woman and the association with libertarian types, the pleasure environments, and the meeting with the object for which he had been brought, affected the spy’s conscience. He was stunned when he did not find the imagined ‘enemy’ in the target; on the contrary, he was confronted with the devout Marxist-Leninist communist, unyielding in the face of difficulties and economically modest, a fervent patriot who did not correspond at all with the archetype of the cunning and criminal traitor, as they had described him, but whose ideals and aspirations were close to those of the ‘assassin.’ Thus, he reflected, and the waters flowed backwards.

Meanwhile, ‘Xhepi’ and his people noticed the intent of the shadow they had sewn to him and kept him under observation, turning him from a hunter into prey; they caught him in the trap he himself set. Thus, the pleasure woman was not merely an instrument of lust, but an agent infiltrated near the suspected subject, acting on party directive.

Meanwhile, the ‘assassin’ became fond of the ‘victim,’ so much so that he enjoyed his company. Consequently, there was no need for counter-action, because the ‘object’ of elimination became an object of admiration; his conscience was troubled by the act he was preparing to commit, and in a moment of weakness, he confessed to the one he was supposed to destroy.

Thus, the double game began. But the Sigurimi works with understudies who usually don’t know each other. This happened with ‘Marrok’ when they realized the double game. They collaborated with the counter-intelligence of the socialist countries and isolated him in one of the embassies of these states, then seized the opportunity and brought the ‘postal package’ to Rinas.

The victim obeyed the captors like a sleepwalker, under the effect of an overdose, and ended up in the basements of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, where they gave him the remaining beatings that others had been spared, and ultimately, the drug on one side and the violence on the other destroyed him physically and mentally, irreversibly.

Nevertheless, thanks to his powerful physique, he survived death. In short intervals, when he regained consciousness, he understood his condition and became aware of the fate that awaited him; as an ‘old hand,’ he had often been in the role of the executioner, where few deserters had managed to escape death, but even those who had succeeded ended up insane. Conscious of the fate decreed for him, he decided to play the fool, a role he consciously entered into and now continues unconsciously, perhaps forever,” Tomor concluded.

The story seemed like an adventure with Arsène Lupin.

“Do you really believe it?” I asked to pinpoint how much trace the saga with spies had left on my friend.

“Certainly!”

“Doesn’t it seem made up?”

“On the contrary, it is more than real!”

“We have heard so many tales that we don’t know how to distinguish the truth from the lie!” I played the skeptic.

“You are right! But the case of ‘Marrok’ is proven.”

“Where did you verify it?”

“In the solitary confinement cell. When he learned who I was and why I was convicted, he addressed me in a moment of clarity: ‘Tomor, now that I know you are Abas Ermenji’s nephew, I will confess an important secret to you. The irreversible role I have taken on does not allow me to get close to you, even though at first glance we seem to be in the same position, it is not so.

‘You are comfortable, because you are supported by your family, relatives, and friends, while I have been abandoned, because they consider me unworthy to be their relative, as I betrayed the trust of the Party and Enver, from the communist perspective. Only my mother follows me, without considering the consequences.

‘As I said, I entered the game of no return. But this must either be finished or, conversely, a sure death awaits me. In truth, I long for death with all my soul, but this would cause a tragedy for my mother. Believe me, I love her beyond madness and I will be forced to continue the act as long as she lives. But we are in prison; no one can imagine tomorrow.

‘Taking advantage of the fact that we are in the same cell and that you are a man of character, I leave you this plea: If something happens to me, transmit what I told you to my mother!’

I swore to him, and he returned to his own madness.

“If it was so secret, why did you tell it to me?” I interrupted.

“For the same reason. You never know, I might get lost in the holes of the prisons, but my honor requires me to fulfill the pledge.”

“I understand. And the second source?”

“Simple; as soon as he hears ‘Xhepi,’ he makes the gestures you saw! Does that need explanation?”

“No!” I confirmed.

“Then the third source is Mr. Nivica, talk to him!” and he concluded. Ahmet also confirmed what Tomor had narrated to me.

And later, the maternal brother of ‘Xhepi,’ Zija Lepenica, who met his brother in Paris after the nineties, following over twenty-five years in prison and forty-five years of separation, when he returned from France, he reinforced with facts what I had heard from Tomor and Ahmet.”

Did I believe it or not?! I’m not talking about Tomor or the other two, but the event itself! I don’t know! Even today I am in doubt…!

Intermezzo!

(A major event, in the light of today’s documents)

I took the newspapers as every morning and glanced at the capital letter headlines, but the news has run dry. Nothing new from the press front!

When my eye caught two portraits of farmers from the Korçë area on the front page of “PANORAMA,” who supposedly claim their produce has rotted: onions, potatoes, apples, etc., they lack a market and have thrown it into the canals!

“Dirty business! Perhaps the ‘bearded man’ loaded them with ground propaganda as newcomers to the old Socialist Party,” I thought, and continued with some ‘opinions’ from opinion-makers that smell of rotten onions and potatoes, then some interviews with former humorists from the onion era, up to the surprise news:

“The Prime Minister’s visit to Afghanistan, to the peacekeeping troops”; then a regulation on how the 2,400 teachers will be evaluated for the expected salary increase; a list of 145 former investigators of the Secret Police and former officers of the glorious Army from the onion era, who crushed internal enemies and imperialist-revisionists of every color, and in closing, a sad piece of news:

“Fuel for police patrols is halved,” which reminded me of the slogan from the onion era: “Savings, savings and savings everywhere…!”

“Oh world, years flow, time stands still, and we are stinking of the onion fumes! Anyway, let me dig through it!” and I flipped the inner pages.

“Eureka! Eureka!”

On pages 18 and 19 of the newspaper……of Monday, April 16, 2012, I encountered an interesting article and was shocked!

Those who have experienced the hardships of the onion era on their backs (naturally, those who are alive), I believe will have felt as I did.

The title:

“The Prayer of the Spaç Convicts: Forgive us our lives, we are young!”

Next to it, four handwritten facsimiles, accompanied by a photo of Spaç prison, naturally from the year ninety.

I devoured both pages and returned to them once, twice, three…ten times. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

“Heavens, we got old, the poor things forgot me!” I pinched myself:

“Is it me or not? Get a grip, brother! Were you there or your shadow?”

The author of the article………hmm, this name doesn’t remind me of anyone!? Could this article writer have been among the flag-bearers of the revolt, and I have lost my mind?! Damn it, my memory is failing me; I can’t even recall my comrades! You’ve gone astray, son…!” I lamented to myself and closed the newspaper.

In the street, my mind was spinning like a neither unseasoned millstone, whose grinding yields neither flour nor bran! “Oh God, amnesia has struck us!” On the sidewalk, I almost crashed into a fellow sufferer.

“Are you going blind, comrade-o?” he shook me by the arm.

“It seems so!”

“What do you see that makes it seem so?!”

“The newspapers!”

“Still with newspapers, you unfortunate soul?”

“What can we do, Xhevo, read some news? Did you see the press today?” I replied.

“Where do the cows leave me to see the newspapers!” he paused, then: “Hey has any list come out for the prison money?”

“No, no!”

“Well, drop it! I don’t have time to spare!”

“There is an article about the prayers that, supposedly, were addressed to the People’s Assembly of the People’s Republic of Albania by Skënder Daja, Dervish Bejko, Hajri Pashaj, Pal Zefi…!”

“What did you say? Repeat it!”

“In the newspaper……they wrote…!”

“Who supposedly wrote?” Xheva interrupted me.

“Them!”

“Get a grip, because you are not thinking clearly!”

“That’s what this says,” and I shook the newspapers at him.

“You’ve gone astray, son, they crippled them!”

“Me or the newspaper?”

“You, because the journalist probably wasn’t born at that time!”

“Maybe! I don’t know what to say!”

“The stretchers that carried out Skënder and Dervish were dripping blood, weren’t they?”

“More than true!”

“Tell me, I beg you, does a dead person write!?”

“No, they don’t write!”

“They were dead, unburied!”

“That’s what I say too!”

“As for Hajri and Pal, I won’t swear on it, maybe they wrote! But not the ones with broken hands!”

“I don’t know what to tell you!”

“When you don’t know, shut up and come give me a coffee.”

We entered the first door we came across; while waiting for the coffee, I flipped through the newspaper and read the article to him from the beginning.

“Bring it here so I can see it myself!”

“Why, don’t you believe me?!”

“I believe you, but not this!” he hit the newspaper. I handed it to him.

He read a passage, raised his head as if to ensure I hadn’t fled, took off his glasses, but seemed to regret it, as he plunged back into reading, turned towards me for a moment, and then back to the printed pages.

“Oh-oh-oh, what the hell!”

“What’s wrong, Xhevo?!”

“My eyes!” He took a paper napkin from his pocket and wiped his eyelids.

“Are you crying?”

“Age, dear friend!”

“Well, what do you say now?”

“I am speechless!” He pressed his lips tightly with his hand. “Not only that, but they are also in handwriting?!”

“Yes!” I affirmed.

“Oh God, we saw them being carried out as corpses, didn’t we?”

“We saw them!”

“Were we drugged?”

“I don’t know what to say!”

“Think, did they throw powder on us?”

“Who, Xhevo?”

“Them, man!”

“I don’t know what to say!”

“But what if those they carried out on stretchers were fake casualties (sampistë – a term for faked wounds/casualties)?” he expressed his doubt.

“Maybe, how should I know?”

“No, no! If you had killed one of them, they would have annihilated all seven hundreds of us who were in the yard!”

“That’s what I say too! But the fact…!”

“What fact? The facsimiles!”

“Hang the bag! They wrote them for procedure!”

“You think so?”

“Well, a dead person doesn’t write, does he?”

“Indeed, how can they write?!”

“It’s impossible, they wrote them for procedure!” Xhevahiri insisted.

“How did they know this time would come?!”

“Oh-u-a, they kept the documents for the museum! Look at the title deeds to be convinced…” Xhevahir Toska left without shaking my hand.

At home, I pulled out the few writings I kept and escaped forty years later. Xhevahiri was right; Skënder, Dervish, Dashnor Kazazi, and Kostandin Papa clashed with the guards; we saw the stretchers dripping blood when they brought them onto the truck bed that transported them toward Tirana.

Naturally, I was not present at the special trial that afternoon to confirm if they were mentioned when they were sentenced along with eight others. But, according to Dash Kazazi’s narration years later, they were taken unconscious to the defendant’s bench. For correctness, I will describe the meeting and conversation with Dash, thirty-three years later. But first, I will transition to the role of the messenger to give him the floor and the authorship. But first, I will describe the meeting with him.

One Sunday in June 2005, I found myself facing a much-desired surprise.

I had struggled in construction for years, but I sacrificed my remaining time to be present at the political activities of my city. As every afternoon, I went to the ‘Skraparllinj’ club, which had become a gathering point for all right-wingers. Naturally, it was not about coffee, because at that time there was no ground floor entrance that had not been turned into a café, but the owners were the sons of a former political prisoner, where right-wingers found each other, exchanged opinions, and organized the campaign to win the July third elections.

It was hot inside, so they had lined up the tables on the sidewalk, so close to each other that customers leaned back-to-back, and no matter how softly you spoke, the neighbor would hear you before the person with you. In our small city, everyone knew everyone, so no one was afraid to speak loudly, especially those days, when the enthusiasm reached its peak, because only two weeks separated us from voting day. Debates buzzed.

“That evening, two men took seats at the table across from me: a former local agronomist, a merchant of agricultural poisons, who was considered a leftist, and the other, a stranger. During campaign moments, especially when tempers flare, the presence of people with opposing views is extremely dangerous. Militants, those with a pronounced lack of education, the mentally ill, or simply quarrelsome types are ready to clash with any opponent of the party they adore.

Thus, those who took seats across from us risked turning into a target board for political taunts and attacks. They sat down, and the conversations stopped; they seemed to be taken as provocateurs, inserted by opponents, just as they consider those who glean information to attack their party’s strength. However, the suspicion faded after the first few moments, the debates ignited again, and the newcomers were forgotten.

The stranger debated with a thundering voice and defended the political line of the Democratic Party. His zeal as a fervent militant drew the curiosity of those present, so much so that from the table next to us, they called the waiter and ordered for the unknown loudmouth:

‘Waiter, two beers for that democratic table!’

‘Is this guys a communist, or don’t you know him?’ a neighbor chimed in.

‘I know him, but the other one is super democratic, though!’

‘How do you know?’

‘Listen to him making politics for himself and for this friend!’

He was truly yelling against communism, using the harshest jargon and a loud tone, with a dialect somewhere from Central Albania. Memorie.al