Dashnor Kaloçi

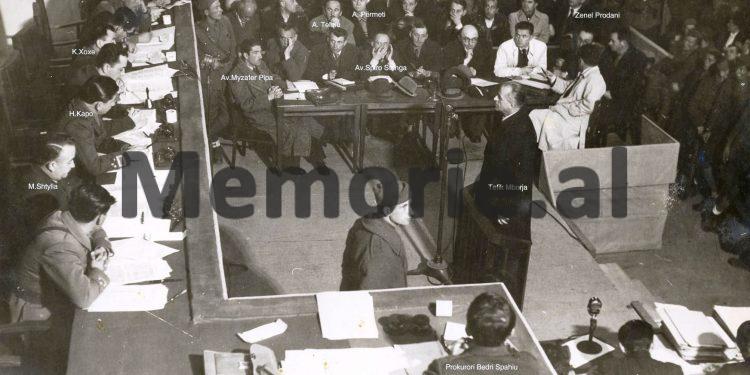

Memorie.al publishes the unknown letter of the former General Prosecutor and member of the Politburo of the Secretary of the Central Committee of the ALP, Bedri Spahiu, sent to the Prime Minister, Mehmet Shehu, during the period he was serving his sentence in the prisons of the communist regime as “enemy of people “. The letter of the former senior official of the communist leadership, regarding the inhuman tortures against him and other political prisoners in the camps and prisons of the communist regime, such as Laçi, Rubiku, Fushë-Kruja, Elbasan, etc., where the most basic freedoms of of the convicts. As well as the autobiography of Bedri Spahiu, a former close associate of Enver Hoxha, who was convicted by him in 1955 and released from prison and internment, only in 1990, when the Deportation Commission was dissolved.

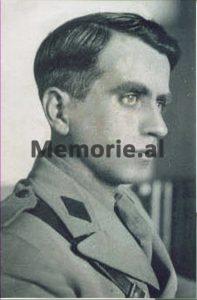

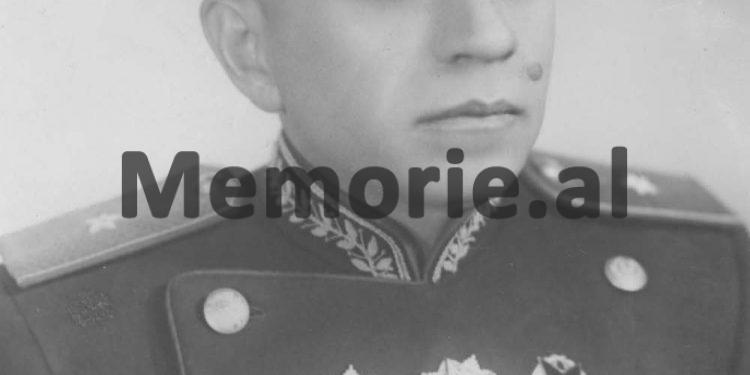

One of those personalities of the Anti-Fascist War and the high leadership of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, who was later convicted as an “enemy of the people” and experienced the most inhuman tortures and long persecution in prisons and internments, has were also Bedri Spahiu. During the years he was serving his sentence in camps and prisons, he wrote several letters to Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu, denouncing the brutal violence exercised by the ruling regime, against him personally and all other political prisoners that the ruling regime considered dangerous. . We are publishing these letters of Spahiu starting from today’s writing, together with the autobiography which he had written with his own hand, after 1990 when he was released from exile and returned to Tirana after 35 years.

His Excellency

Mehmet Shehut

Chairman of the Council of Ministers Tirana

Allow me to present to you the second part of my Testament. Circumstances brought him that I could not restrain myself without worrying once and for all. I am not going to go into details because I have nothing to add after the cover letter of the First Testament.

Sincerely, Bedri Spahiu

entry

It is known that wills are usually made on the verge of death, but sometimes it happens that the drafter survives and has to make a second will, when death knocks on his door again. This is also my case. To people in general, survival is the result of a renewal of human health, while to me it is the result of a renewal of the legality of the Republic in the field of prison administration. In fact, in early 1966, convicts suffering years of solitary confinement were brought to light from the Isolation rooms of Prepotence; able-bodied and semi-skilled prisons were given the opportunity to camp, starting from a “humanist” goal: “not to rot in prisons”. Prisoners who were not able to work enough or who dared to come to the camp, lest they have a hard time working there, were encouraged by officials, that in the camp they would be much better than in prison and that no one would not ask for more work than they could do. Life proved that these encouragements were sincere and the prisoners in question were satisfied. The encouragement and use of brigades to beat imprisoned workers was abandoned. The brigadiers threatened to be criminally punished if they subsequently beat the prisoners. The illegal officials themselves declared with their own mouths that the beating of prisoners was no longer allowed even by the officials themselves and that only the penalties of the regulation and, if the case were the case, those of the Criminal Code would be applied. The relations of the prisoners with the administrators were established on the basis of law and regulation, on the basis of state legitimacy and thus of human dignity. Prisoners began to be treated no longer as savages of the tropics, huddled in a ravine to be exterminated, but as people condemned by the law and to be held and treated neither better nor worse than the law dictates and written, promulgated, official, publicly recognized regulations. Prisoners began to be told a kind word about their productive activity in the field of construction work. The one-sided claims of the prisoners that the state punishes people for using them as captive power, that all acts in Albania are with their blood and sweat, were no longer answered by the equally one-sided claim of the officials, who told them to the prisoners full of nervousness: “Not you, but the people build the works in Albania. You are enemies! We will make you work inadvertently until the last breath. ” Yes! Such a practice was abandoned. They began to be told that they were contributing to the construction of the works and that they would give it when they were released from prison. They were no longer told that any danger was happening, we would exterminate all the prisoners first “, that” the trial is a gramophone, which sings the record put by the investigator “, etc., but they were told that even though you are punished by the laws, you are Albanians, you are the sons of this country, because you will also fight if the Homeland is attacked, because we have it in common. The prisoners were told that those who behaved would be taken in groups to see how the works they had built and those built by the people would work, that sports matches would be organized between the camps, and that the general treatment of the prisoners would improved. What hopes, beliefs, illusions were raised with the prisoners! A spirit of optimism like a spring breeze described the troubled souls of the prisoners. What is true is that this new line of administration was not and could not be a turning point. On the other hand, she faced opposition from the base’s illegal officials, which I put in a letter I sent to the Ministry of the Interior on May 14, 1966. This opposition was evident. It was an attempt between the legal and illegal administrators of the base. The contradiction was overcome in a positive way. Legality came out strengthened by this effort. In the conditions of this renewal, the ugly old opposition of the administrator: cruel administrators and administrators with legal nobility, facing each other disappeared. In the conditions of this renewal of legality, the illegal officials themselves were renewed. They became more reasonable, more objective, more realistic, more prudent, less harassing, less quarrelsome, and less arrogant. There was a turnaround. It began with a 180-degree theoretical turn based on Lenin’s thesis: “Dictatorship is a power unlimited by law.” 38 theses that before the restoration of legality were thrown in the faces of the prisoners whenever they complained about the violation of their legal rights. Since from the general point of view there is no identical repetition, even this thesis was not thrown at the prisoners this time in their classical form, but was thrown at them in a new dress: “We have in our hands the dictatorship of the proletariat . “We act according to laws and regulations, but for those who break the laws and regulations, they also use Dictatorship, Violence, Wood.” I said above that there was a 180 degree turn in theory, that the renewal of legality was carried out on the theoretical thesis that was proclaimed in the “Voice of the People” in September 1965, according to which only the state has the right to change the laws, to do new laws and suppress those that are not appropriate. Officials are not allowed to disregard laws under any pretext. What is good for the state, for the Republic, for Socialism, is contained in the laws of the state. It is clear that the above-mentioned thesis of the base administrators and that of the “Voice of the People” are antithetical. The interest of the prisoners as a whole, wanted the renewal of legality to continue. The interest of the state wanted to continue. Here we are dealing with a phenomenon that may seem strange, but wonder is a form of ignorance. Convicts from the state and the state itself have a common interest. This is the wonder. Contradiction! But you have nothing to do with it! And what is not contradictory in this world? The community of stakeholders in the case in question is explicable. The state of any social system (slave-owning, feudal, bourgeois, socialist), of any regime (absolute or democratic), of any form (monarchical, theocratic or republican) has not only a class function, but also a non-social one, that is, it serves something even his class opponents. The man may be a three-horned revolutionary or a five-horned opponent of the state, but when attacked by someone with a knife in his hand, he will come to hide behind the public security guard. The process of renewing the legality could not but be contradictory in the field of relations between the officials under consideration that, while the legal officers would be caught by the new, the illegals would try to keep the old one. The same process was contradictory in another way. In fact, while illegal administrators continued to violate the line of lawfulness renewal from administrator positions, undisciplined prisoners violated this line of legality from anti-collective positions. Thus, if the interests of the collective in the prisoners coincided with those of the state, at the same time the action of the official illegalities against the line of renewal was inconsistent with the actions of the undisciplined prisoners. Both sides shook hands with opposite barricades, the two sides continued to behave as before the renewal, we provoked the undisciplined and the sick with nerves, and these instead of defending themselves with certain means from the repeated legality, overcame them. targets of this and used unauthorized and in some cases even unreasonable means. In the conditions that set forth the proclamation of the theoretical thesis of the opposition of dictatorship to the very laws of dictatorship, the balance could not be turned in favor of arbitrariness. Of course renewal could not be fused with the speed with which a thesis is thrown, but the process of this fusion has begun and will continue. It is the practice of the theoretical 180 degree turn. There began to be nervousness again among the administrators, official illegalists are reactivated; water shovels are taken from them; what in the period of renewal was seriously called “Rehabilitation Ward 323”, illegal officials now call “… Rehabilitation Ward”, as some prisoners called it when it was called “Rehabilitation Ward”; swearing, wood, irons, wires, come out on disciplinary measures according to the regulation. The nervousness of the prisoners increases in parallel with the nervousness of the administrators. Prospects for improving living conditions were clouded. The fact that all prospects for release have been closed to the prisoners and that they will be sentenced to… all years of imprisonment is also a factor in this situation. Those parolees that are made are such (few even these are the cases of convicts who are at the end of the sentence) that provoke the humor of the prisoners, the work has reached the point where when it comes to rehabilitation; for parole, the prisoners laugh ironically.

Loss of hope by convicts

To the prisoners, in short, we close every perspective; hope, faith, illusions, gave way to the abyss of disillusionment, optimism-pessimism. In these circumstances the sincerity of despair appeared in the prison staff. In meetings organized by command personnel or in occasional meetings with officials, prisoners convicted of guilt or for crimes they did not commit openly protest; the tortured show wounds and old and new trials. The ideological, political truths and arguments of the officials, the prisoners openly opposed their truths and arguments. Prisoners, by and large, no longer hide what they have suffered unjustly and their thoughts. Prisoners have no interest in hiding them. For their part, even prisoners convicted in accordance with the law do not hide their opinions and defend them. Alongside the sincerity of despair appeared the heroism of despair, a phenomenon that existed before the renewal of legality in 1966. In the Laç camp, three prisoners broke the siege by truck. The administration responded by killing one of them and severely punishing the others. He left the body of the murdered 24 hours in the camp yard, at the feet of the prisoners. She confronted individual escape with collective tromax. Extreme repression and collective thrombosis did not yield the expected results. After 15 days, two prisoners repeated the attempt from the camp, Fushë-Krujë in the same way and means. One of the perpetrators justified his attempt as follows: “I knew I had no chance of escape, but I only tried to be killed. I do not want to live anymore. I came to prison as a child and I am getting older. Why didn’t you kill yourself? “It seemed easier to me to be killed by the other hand.” In the conditions of the turn towards arbitrariness, the contours of three processes are crystallizing: The process of administrators nervousness and prisoner counter-nervousness.

Reproduction of extreme repressions, exemplary repressions, preventive repressions, blood-based repressions, false repressions on the one hand; the frankness of despair and the heroism of despair on the part of the prisoners.

The process of strengthening the positions of illegal officers and weakening the positions of legal officers. I do not want to prophesy, but what seems to me to be otherwise will be the issue that the frankness of the prisoners’ despair and heroism of despair will give way to the panic of repression. Prisoners will receive a severe blow when they do not suspect it and as a counter-reflex of this panic in the ranks of administrators the panic alarm will appear. Legal officials will begin to realize that the provocateurs of panic are the illegals of their ranks

Bedri Spahiu

Autobiography of Bedri Spahiu

I was born on July 13, 1908 in a farming family in the Palorto neighborhood of Gjirokastra. My mother died when I was 10 years old. The father in April 1944 came and took home two ballistae and killed him in a stream. The body was never found. During my childhood the economic situation of the family was very dire. My father, Sinan, went to the curves (in Turkey) hoping to recover. He made his second attempt in 1922. During this time I was in elementary school and by 1923, I had completed 4 grades with excellent grades. Unable to afford the remaining classes and gymnasium, on May 16, 1923, he left for Izmir, where his father was staying, hoping to continue his education. Even before he got well, my father started talking to me about “work”. “I did not come to work,” I told him, “but to continue high school.” He told me about the difficulties we had as newcomers in a foreign country, without support and without wealth. The desolate old man. He spoke with the logic of life, but it was a knock on the door of the deaf, that I was obsessed with the passion to continue school. After some time I tell my father that a borshiot, Hidajet Xhuveli, who was a servant in the Italian consulate in Turkey, had undertaken to admit me to the Salesian school. Waiting for September to start school, he asked me as a reward to teach his son Albanian. Since the Salesians had high schools in Istanbul and Cairo, I hoped to continue there after finishing those elementary years I had left in Gjirokastra. So I finished Italian elementary school in Istanbul and got my release certificate, but my plan was blown up by the doctor. He advised me to stop studying because I had severe anemia. “It is impossible!” I replied. “Of course,” he told me, “it’s bad to interrupt my studies, but Meglio un asino vivo che un dottore morto!” Desperate, I return to my father and start tending cattle with him. Apparently, from the fresh air, from vacations in diverse nature, my health started to come back again. Meanwhile (around July 1927) the ambassador of Albania in Ankara, Reuf Ficua, comes to Izmir. In these circumstances, my old passion to continue my studies was renewed and a new hope pushed me to turn to the ambassador for a scholarship from the Albanian state. He saw the school transcripts with very good grades and “Attestato di primo grado” and looking me straight in the eye, he answered me. Yes! You will have a scholarship. From mid-September 1927, I was at the Ministry of Education in Tirana waiting in line to be introduced to the Secretary General. As soon as I opened the door, the secretary stood up, happy and confused. “Bedri!” – he said.- “How well you came yourself. I know I know. Reufi wrote to us. I made the act ready for the gymnasium of Shkodra. Now lead yourself. Hajt, good track and success! ” This was Thoma Papapanua, that teacher from Gjirokastra who in 1923, mediated to Javer Bey to be given a scholarship to continue school. I started high school after five years of wandering. Five years sacrificed on the altar of fukarallëk. But for this loss, I did not even think in those days. The main thing was that I had received a scholarship and I was provided with a gymnasium. But was it insured? In the spring of my second year of school, I received a conscription form. The principal requested the postponement until the end of the school year. The call was arbitrary, that I was an only child and consequently excluded from military service. I addressed you Fuat Kikinos, head of the Recruitment Office, but to no avail. Upon leaving this office, I come face to face with Pandeli Dilon, a resident of my neighborhood. “Are you deserted!” Pandeliu said when he found out about my plight. “How come you did not come forward a little! “In half an hour you lose a good opportunity.” Pandeliu told me that in the barracks opposite, a year ago the School of Artillery Officers had opened (with Italian teacher officers) and that this year a competition for young students had been announced and that half an hour earlier the deadline for submitting prayers had expired. . “However,” Pandeliu added, “I left the captain in the office. Let’s go once. “Maybe he accepts the prayer.” It was one of the most difficult moments of my life. I had been born the day of a bad star for regular school, but now it had to be decided whether I would agree to go soldier and, after completing my service, be thrown into the platoon of the unemployed, or whether I would agree to enter the school of artillery to have after two years a secured salary, with the hated service of the officer. I accepted the latter and started the Artillery School in Tirana. But what was my ideal at the time? To make this clear I have to go back to the period when I lived in Izmir. I stayed in Turkey for 4 and a half years, from May 16, 1923 to September 15, 1927. I spent two years in the school where I had provided accommodation and food. Two and a half years I made the life of the curve. This life was a struggle for housing, for food, for work. I worked in several jobs. Privileges were our fellow travelers. I went to Izmir with the ideas of Albanian nationalism, with democratic and republican thoughts. Love for people, compassion for the suffering, social inequality, did their job. We add here the dizzying Soviet propaganda that was entering Turkey at that time. I experienced in the most natural way the ideas of the October Revolution and returned to Albania with communist convictions. I devoted my whole life to communism and it took a long individual and collective practice, in building the state and national life, to be convinced that the nation of any system is prospering, but poverty and destitution are reproduced within prosperity, that despite system and by the degree of prosperity, the nation is obliged to apply the differentiated distribution of national income and to have a coexistence formed by accumulators and workers. It is a belief invented too late, but better late than never. So I divorced communism. The period of my life with communist ideas in time is divided into three phases: The first phase begins in September 1927 and ends in August 1931 (at the Artillery School). At this stage my activity is communist propaganda at school. The second phase begins in August 1931 (in Zog’s Army) until October 1941. In Zog’s Army I created the “Communist Military Group” (perhaps it would be better to call it the “Military Circle”). On June 11, 1937, I was arrested as an officer along with most of my bandmates. The Fier uprising had failed and since we had connections with them, we were arrested on the charge: “Participation in it, subversion in the army and communist propaganda.” After 7 months, the investigator released me and Tahir Kadare and deported us to Gjirokastra. In 1938, I was arrested together with Tahiri in Vlora, as soon as they got off a Yugoslav steamer where we had boarded in Saranda under false names, to go abroad. From Vlora I ended up in the dungeons of Gjirokastra, where the place of internment was. During the time I was interned in this city, I created the “Communist Group of Gjirokastra”. At the Gjirokastra Conference, I was elected the first secretary of the party for Gjirokastra and later the political commissar of the Vlora-Gjirokastra districts. When the General Staff was formed, I was a member of this Staff. In Berat I was elected a member of the Politburo and held this position until June 17, 1955. The second phase as a communist (and which included the period August 1931-October 1941), has to do with the organizational form of my work. The results achieved with one or the other individual, I reinforced with a constant propaganda work. I was a hunter of people I needed, so much so that my friends named me “Kaçatori”. The third phase begins in November 1941 (the founding of the Party) and ends on June 17, 1955, when I was arrested as soon as I passed the door of the hall where the plenum of the Central Committee of the ALP took place and was isolated for five days in a house. This came as a result of my long struggle against the policy of Enver Hoxha. After 5 days, on June 23, 1955, I was interned with my family in Elbasan. On June 1, 1957, I was arrested and isolated in Kanina Castle in Vlora, from where I was transferred on January 4, 1958 to Tirana. I was sentenced to 25 years. On October 6, 1974, I was released from prison and interned in Selenica. I was released from exile on May 10, 1990, the day the Deportation Commission was disbanded. My first arrest was in 1925 in Turkey, when I refused to speak Turkish. Charges: “crime of using the mother tongue”. Second on June 11, 1937 in the Bird Army. The third in 1938 when we escaped with Tahiri. The fourth in November 1941, for organizing the laying of tracts together with Bajram Sinoimer. March 13, 1942, I am arrested betrayed by a golemas. Sixth on January 4, 1958, now as an enemy of communism. I have been interned 4 times; in 1934 before Count Ciano came to Tirana, on September 15, 1937, when I was released from the military investigation. On June 23, 1955 in Elbasan when I was expelled from the Party. On October 6, 1974, I was released from Burrell Prison.

“Glory to God!” – said my grandfather, when it came to the state- “I passed the hundred and did not see the door of the Judgment, neither for good nor for bad”. It’s up to his nephew to say: Glory to God! All state regimes have arrested me, only for political issues./Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)