By Tarik Llagami

Memorie.al / He was doing his shopping. He held the bags of eggs and quietly waited in line. He was going to buy meat. Suddenly, the party’s soldiers came from behind and arrested him. He was shocked and bewildered. He tried to think of what he had done, but his mind was like an empty field. As they grabbed him and handcuffed his hands, the bags fell to the stone ground. The people around pointed their fingers at him and called him a reactionary. They shouted as loud as they could. Some others felt sorry and turned their heads away. Perhaps not to see their own possible future. They were also reactionaries. Everything flashed before his eyes like lightning. This cave candle was now lost in the tunnel for himself. They left the people and dragged him to his house. They beat on the door with fists and kicks.

The people in the house rushed to the door, somewhat frightened, because even without opening it, they knew what to expect. They had experienced the fate of this knock before: a man held by several soldiers. The crowd watched with contempt and pleasure at his suffering, but there was also a group of soldiers passing by chance. They recognized him. They considered him a brother and wept for him more than his own family; “This man and this family do not deserve this fate. This black fate.”

He was born in Tirana in 1913. His father, Myslym Llagami, was a Rilindas (National Revival figure), and also the first licensed lawyer in Tirana. Consequently, his son would also be an oppositionist seeking the development of his own country. His father sought Albania’s independence from the Ottoman Empire and was imprisoned for it. He was jailed three times: by the Young Turks, the Yugoslavs, and, of course, the Albanians. He died when his youngest son, Fiqiri Llagami, was only 3 years old. But how did Fiqiri Llagami manage? How did he live his life? Was he simply an orphan, or is there more to this story?

The Early Oppositionist and the Sorbonne Student

Fiqiri Llagami had excellent results in high school. In addition to his excellent grades, he was elected chairman of the society “Fryma e re” (The New Spirit). He also wrote articles in numerous newspapers, such as: Gazeta e re, Drita, Besa, Shqiptarja, Shekulli i ri, Shqipnia, Njeriu, Tomori, Java, Kuvendi Kombëtar, the magazines Vatra, Ora, etc. But it does not end there, because at the age of 20, he published the book “Studime kritike mbi njerëzit e mëdhenj” (Critical Studies on Great People).

In 1931, he wrote the article “Amikus” in the newspaper Shqipëria e Re. This was an article with opposition content against the government of Ahmet Zogu. As a result, he was arrested by two police officers and held for three weeks, just for daring to express his opinion. We can say that his “tainting” of his biography had begun here. There is a record about Fiqiri Llagami dated October 6, 1957, kept by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Branch I, no. 8, “Materials available for Fiqiri Llagami.” There, the communists documented his life before and after the regime’s arrival.

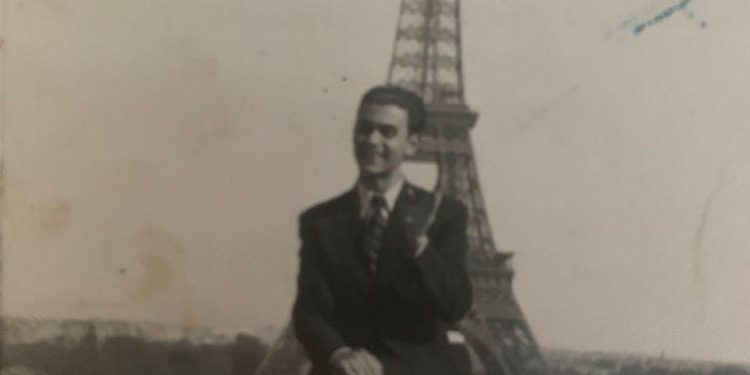

In the 1930s, when he was an excellent student at the Tirana Gymnasium, Albania did not yet have a university, and students had to obtain scholarships to study abroad. It was mandatory for them to return to the homeland to contribute. If they did not return, or if they failed a class, they would have to pay the value of the scholarship. There was no other option for Fiqiri Llagami but to study abroad. After being stalled in ministry offices, because they were hesitant to grant him a scholarship due to his opposition principles, he finally received a half-scholarship to study in Paris.

Despite many obstacles, he managed to get the scholarship of 120 francs per month. He was the first Albanian to study Journalism at the Sorbonne University in Paris. Of course, in France, he had to promote Albania and constantly report to Musa Juka, the Minister of Internal Affairs. Out of a love for studying, he made a compromise. He agreed to the conditions and presented himself as an admirer of the King when he spoke at the “International Peacekeeping Meetings” about the stability of the Albanian people. At this meeting, published in several French newspapers and attended by Mr. Leon Rey, Fiqiri Llagami made Albania’s name known in Europe for the great intellectual potential it possessed.

Imprisonment and the Pursuit of Free Press

When returning to Albania from France, he was arrested by Italian carabinieri in 1942, where he was kept in isolation for three straight months. After being released, he returned to his homeland. Since he had economic problems and refused to work for the occupiers, he sought to work as Vice-Mayor of the Municipality of Tirana. In his opinion, this was not a political post. He had written a letter to Mustafa Kruja and Kolë Bib Mirakaj, explaining his reasons for seeking that position. Even though he deserved it because of his education, the post went to someone with more political backing.

Now, unemployed, he had to do something, he had to find work, he had to live somehow. Even though it was a job far beneath his level of preparation, he started teaching French at the Women’s Institute of Tirana, an institute he founded himself.

Perhaps there was light at the end of the tunnel, because Rexhep Mitrovica’s government declared that the press was free. Hope was born. As a journalist at heart, the only thing he felt he should do was open a newspaper. So, he opened the newspaper “Shqipnia.” He spoke about the unification of Albanian lands, the development of youth, the eradication of fratricide, and the denunciation of those who had collaborated with the invaders against their own country. Some of them were: Mustafa Kruja, Hilmi Leka, Kolë Biba, Maliq Bushati, Qazim Mulleti, etc. But apparently, even freedom had a limit.

Later, he was served an arrest warrant by the Tirana Prefecture. It was expected; freedom could not come so quickly and effortlessly; freedom has always been difficult to achieve. Fiqiri Llagami knew this and continued the fight for freedom of speech. He did something well-thought-out to achieve his goal. He interviewed Abaz Kupi, the head of the Legality Movement, to talk about the Kosovo issue. The interview was published and was much appreciated by Mitrovica’s government because it aligned with their convictions.

The goal was achieved. As a result, he was allowed to continue writing. (Fiqiri Llagami told all this before an investigation commission, formed by: Sino Zhupa, Delo Balili, and Jahja Hatibi, and they were discharged in a record dated May 11, 1961). Even though he had initially been promised freedom of speech and thought, the words were lost to the wind. The newspaper was closed down because it was in deep opposition to the agenda of the Fascist invaders.

The Double Victim of Two Regimes

Fiqiri Llagami was accused as a Communist during Fascism, and during Communism, he was accused as a traitor and war criminal. He was neither of these. He was a visionary for his own country, a man who sought the best for the homeland. He would not accept his country being torn apart by borders, and he would not accept his country being occupied. The flag of Ethnic Albania hung in his house, because that is what he aspired to.

Why was it so wrong to love your country and defend it with free speech? These stories of the Communist takeover, which arrived in 1944, may seem unimaginable, incomprehensible, and even indigestible when we read them today. Back then, it was part of daily life. It was normal for even the walls to have ears. It was normal to be imprisoned for what we call nothing today.

The Communist regime had not yet been fully installed, but it was led by the future dictator Enver Hoxha, who knew the objective well. The objective was the subjugation of the people by eliminating opposition. The first to be eliminated were those considered the most dangerous—the most dangerous for preventing the advent of the dictatorship. Therefore, as soon as it came to power, the regime began to eliminate oppositionists, one by one.

Fiqiri Llagami was among the first to be labeled “enemy of the people” on April 13, 1945. This was the date when the Special Court was held, in which he was unjustly sentenced to 20 years in prison, confiscation of assets, and deprivation of liberty. After the trial, he was imprisoned, and the soldiers went to his house, turning everything upside down. In front of the family’s eyes, chaos erupted in a few moments. They took everything, even his wife’s dowry. In this infamous trial (the Special Court), over 60 people were brought before so-called justice, and in the name of justice, only two people were declared innocent. The others were sentenced to prison or execution. All this; “in the name of the people.”

He was accused of being a tool of enemy propaganda and a propagandist journalist. Of course, he denied both of these, because they were not true. The truth was this: he had not been involved in political activities since 1935, when he finished his studies in Paris, except for the publication of the short-lived newspaper Shqipnia. He had not published any opposition newspaper for about 10 years. The truth was being manipulated, invented, and played with. Even though his only quasi-political activity was criticizing the invader, he was still condemned.

The truth is that the regime was not looking to discover the truth but aimed to eliminate progressive people. They had the potential to bring about change; they necessarily had to be eliminated first. If they didn’t imprison him, they knew that one day he would start speaking. So, to be safe, they arrested him too. After all, why not do whatever you want when no one stops you?

A significant part of Fiqiri Llagami’s life was prison. In April 1945, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, but fortunately, it was reduced to 10 years on the occasion of November 28th, the anniversary of Flag Day. How ironic the regime was, releasing an imprisoned patriot on the day of independence. But at least he was freed. He was freed and interned in Lushnje. Initially, he was to stay for one year, but the party-state proved “generous” and gave him a few more years, keeping him there for 7 years.

So, he served 10 years in the Tirana prison and 7 years of internment in Lushnje. He must have truly been the regime’s “favorite.” But now, the prison and internment end, and another phase of life begins—one not unknown to him: unemployment. He was not allowed to work, so he sank into poverty. Fiqiri Llagami knew 6 foreign languages. He spoke Latin, French, and Italian fluently and had knowledge of German and English. He was tireless and was an example of the saying: “As long as you live, you will learn.” He was a strong man who let nothing defeat him.

But they still did not let him work. So, he gave private lessons and was forced to walk every day from Kinostudio to Kombinat.

However, the prison chapter was not yet over. In 1975, he was arrested again, but this time the party proved even more “generous.” He was accused of: “agitation and propaganda against the people’s power.” He was sentenced to 8 years in prison, but he could not complete them. The party once again showed its “charity” by helping him “escape” this hell, through poisoning.

He passed away in 1978, and they said he had pancreas problems, but his family deeply believes he was poisoned. Beyond all this fog, there was still fog…! His family was notified very late and was not informed of his grave. Three children with their mother, without a grave to mourn their father!

Death in prison is the saddest death. It is unimaginable to spend your last days in a cell and then in a hospital. Don’t criminals deserve this? Was he a criminal? Certainly not. Fiqiri Llagami spent about 20 years in prison. I believe his story needs to be heard. I don’t think this just because he is my relative, but because he gave so much for the homeland and received nothing. He received nothing but a life spent in prisons. In fact, many were imprisoned; it was not unique.

But Fiqiri Llagami was different; he was targeted and imprisoned before the regime was fully installed. This shows how dangerous he was to them, because they didn’t wait. He did not deserve to be treated that way. He did not deserve to be imprisoned and left unemployed. He did not deserve to have his mouth locked and his newspaper burned. Fiqiri Llagami did not deserve to die imprisoned and have his grave unknown. / Memorie.al