By Blendi Fevziu

Memorie.al / Mr. Durand, let us begin this conversation with your first arrival in Albania. In the preface of a work by Ismail Kadare, the manuscript of which you smuggled out of Albania, you speak briefly about your first urgent trip to our country in 1986. In fact, what pushed you to come to the writer’s country – one of those whom the “Fayard” Publishing House has been publishing for years – and why did you repeat your visit in 1990?

My first trip was in 1986 because Ismail Kadare could have had problems. My second trip, in 1990, was even more important. It concerned Kadare’s departure. It was a moment of turmoil, the historical moment of the fall of the dictatorship and the establishment of the democratic regime. We had prepared everything beforehand. His family was to come to us in Paris for a vacation. We took the opportunity to pack suitcases containing archives and the writer’s manuscripts. We left with Ismail’s younger daughter, while the elder daughter was already in Paris. We departed from Rinas without much difficulty. He was to follow later, invited by me as his publisher.

You said that Ismail Kadare’s fate was at risk. From whom, and was he afraid?

Yes. Kadare’s fate was at risk from the dictatorial state. Isolated from the world, he and many others were suffocating. I think that under such conditions, many people sought a symbol, a sign to show they were alive, and as a form of pressure on the international community. During my second trip in ’90 – a time when the dictatorship, though in its death throes, began to reawaken once more just before breathing its last – anything could have happened. Kadare felt it was crucial for him to leave and that his departure was a political act. This act created an “electroshock” in the country. There are moments in history when a country’s fate hangs in the balance and can swing from one extreme to another. In that period, Kadare left not so much because he was threatened, but to perform this very positive, political act.

Was it difficult for you to fulfill your mission in Albania regarding the retrieval of the writer’s manuscripts?

No, because I was risking nothing. I might have had more problems in a dictatorship like the Cuban one. I have never been to Cuba, even though I have published dissident writers from there. There, it might happen that they plant a load of drugs in your car trunk and then stop you. In Albania, such a thing was not going to happen to me.

Has the writer been your only link to Albania? How have you found this country in three different eras of your visits?

On my first trip, I found a country that was, I would say, civilized. I remember we stayed at Hotel “Dajti” and were not allowed to have contacts. We were completely isolated. We were accompanied by a translator who was clearly more than just a translator. Of course, we were bugged everywhere. When we went to Durrës to speak with Ismail about the future, to examine the difficulties of leaving Albania, we discussed all of this in the sea. It was the only way to have a completely secret conversation.

Has there been any secret that, taking advantage of this interview, you might entrust to us – a secret of the kind between you two that the writer himself has never declared?

It is something that Kadare himself has not declared. After my first trip to Albania, the major French weekly L’Express published an article about the last “gulags” in Europe, and a part of that article concerned Albania. It included a map showing the regime’s camps and prisons. It was not one of the collaborators of my publishing house who created this. I only took the data, and it was Ismail who informed me about everything, so that the Western foreign press would know the locations of torture and internment camps in Albania.

Kadare has never said this, and I am saying it now. Thanks to him, the West learned of the regime’s punishments in the Albania of that era. But you asked me how I found Albania. I told you: on the first trip, a civilized country; on the second, an Albania in anarchy. But the worst could have happened. As I said above, an external element was needed for the country to move in the right direction, as it seemed it might descend into civil war.

And now you visit after 14 years…?

The truth must be told. It seems to me like a country being reborn – Lazarus – like; I would call it, in the biblical sense. It was in a coma, dead. Now, like Lazarus, it is being held by the hand and obeying when told: “Rise and walk.” This is immediately visible. I saw it in Tirana, which looked to me like a growing garden. In the constructions – sometimes anarchic because they have increased so much – it nevertheless grows and grows.

Despite the criteria required by Brussels, Albania seems to me on the road to Europe. But I must add that it is mostly the Albanians who are moving faster than politics; it is politics that should be at the forefront of its people.

However, you haven’t told us how you met Ismail Kadare?

It happened in Paris in the early 1980s, when I was taking the post of President of the “Fayard” Publishing House. In 1983, I met Kadare in my office. He was accompanied by the cultural attaché of the Albanian Embassy in Paris and the Chairman of the League of Writers and Artists of Albania, Dritëro Agolli. So, we did not meet alone. The meeting was cordial but very formal, very protocol-driven. After that, I was often invited by the Albanian Embassy, where I was well received, despite the heavy shadow cast by communism and the conversations where one had to be careful. I remember a ceremony at the Embassy.

I did not want to cause a reaction, but I spoke about literature – good literature that, like a pebble in the shoe of a dictatorship, prevents you from walking and makes you limp. The Ambassador asked for my speech immediately and put it in his pocket. These are episodes…! However, I was received in a friendly manner by the people of the Embassy, even though we knew well how difficult our relations would be. After the ’90s, I met former ambassadors and cultural attachés who, in the early hours of democracy, had turned from communists into democrats. So you see, their conviction was not that pure or deep.

Why did you decide to publish Kadare’s work?

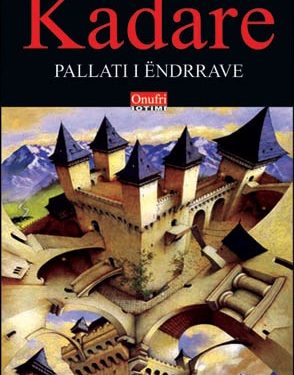

I must emphasize that we publish it in both French and Albanian because, for us, it is a special case. I published it in French because from the beginning, I realized that Kadare would be one of the greatest classics of contemporary world literature. Everything had to be preserved. We had to leave a mark with the final publication of his complete works. This meant we would guarantee the author the quality of the translation and provide the definitive version of the work, including works censored in Albania. And why in Albanian? Because in that era, there were no publishers ready to risk all of this. Furthermore, today, for translation into the languages of the world, we offer the definitive texts from this collection.

Besides publishing it, is this the literature you prefer?

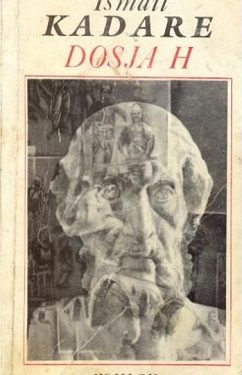

His literature includes many genres: novels, poems, short stories, and plays. My favorite novel is undoubtedly The Palace of Dreams. Then there is The File on H and all the “Ottoman” novellas – those dealing with the Ottoman period and the Albanians’ struggle against the Ottomans, such as The Blind Firman or The Castle. I very much like what he has written about Aeschylus in the essay Aeschylus, This Great Loser, an intimate essay, a personal reflection on the classic. I know he is working on another essay, but one shouldn’t speak prematurely. For me, Kadare’s work is one of the five most important creative bodies of work in the world. He is one of the major writers of the era. Everything we have done to protect this work seems perfectly normal to me. In fact, we are the ones who are still in his debt.

Mr. Durand, in Albania, the debate over opening the files of writers comes and goes—files that should testify to the punishment of literature and arts in general, and the artist in particular, in the past. According to your experience with the literature of the Communist East, or literature written under the pressure of a totalitarian state, should this act be followed through to the end, and how can civil society face it?

We have just published the work The Red Pashas – Investigation into a Literary Crime by Mr. Maks Velo. This work and the goal it expresses regarding the opening of archives are very important. The situation in Albania reminds me of 1968, when I published a file on the difficulties Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had faced at the Writers’ Union in Russia. It is the same approach. Archives must be opened so that evil does not repeat itself. It is not about revenge or reprisals, despite the mistakes some made, including criminal acts. The truth must be told, and history must be known. I believe there is no strong democracy if history is falsified. This is a duty toward the future of children and the generations to come. To erase history means that they too might one day fall into the same errors if they are not shown what evil and misfortune communism and ideology created.

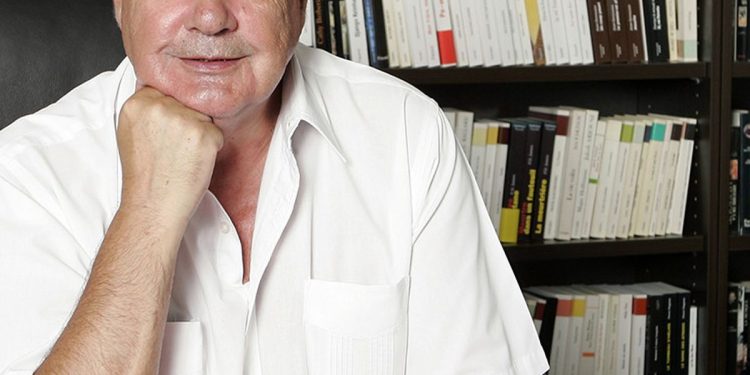

Since 1980, as you mentioned, you have been the president of an important and historically significant publishing house. Who is Claude Durand, and how did he get here?

I was born on the outskirts of Paris, in what is called the “Banlieue rouge” (Red Suburb), which bustled with factories and workers. A simple environment. My father was an accountant. I did well in school. To pursue studies, you either needed money or to run elsewhere. One of my teachers entered me into a competition to attend a school for teaching, a “Normal School.” Very quickly, I became a teacher. I started teaching at the same school where my first teachers had taught. I was 18, while my students were 14.

This lasted for several years, but I wanted to do many other things beyond that. I got involved in politics, I was active in the Association for the Defense of Human Rights, I was involved in theater as an actor and in cinema as a director – I did many things. Meanwhile, I was also involved in literature. During this time, I had contacts with publishing houses. Someone there asked me to read manuscripts by beginners and report on them. So, during the day I taught, and in the evening I did this work.

At the age of 25, I was asked to leave teaching and engage in publishing at “Les Éditions du Seuil.” I was involved in publishing the works of many young writers, with Russian literature, and later with Spanish literature for their international presentation – meaning verifying all translations, because many writers of that era coming from Eastern countries were protected by the Berne Convention. For this reason, there were often anarchic translations through Switzerland. I only need to mention the case of Solzhenitsyn. So, I had to bring order to all the countries where Solzhenitsyn had not only been poorly translated but also pirated.

When speaking of your experience as a publisher, the first writer who comes to mind is precisely the Russian dissident and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Have you recently published a work of his?

I have been involved with his work since the ’70s. Yes, recently we published a book that has been highly discussed in the West and is very bold: a work on the relations between Russians and Jews in Russia. It is in two volumes: the first speaks of the resistance of Russians and Jews under the Tsarist regime, and the second about resistance under the Communist regime. Solzhenitsyn has done very good work with the archives.

Another issue not well examined here remains that of dissidence. Since we are talking about literature and the fact that you have dealt for a long time with Solzhenitsyn’s work, let’s stop at dissidence in literature. What is a dissident?

It is very important to answer this question. I think there are several forms of dissidence. The simplest form is what we find in many Eastern countries, like Russia, Albania, or elsewhere: exile. The choice to leave the homeland, though not by your own will. In my opinion, this is not dissidence in relation to the struggle that a writer or intellectual wages against a dictatorship by deciding to stay in their own country. Here we are dealing with the highest level of dissidence: resistance. We just spoke of Solzhenitsyn.

Many say it was he who decided to leave, to leave Russia. No! He refused to go collect the Nobel Prize in Stockholm because he knew they wouldn’t let him return, just as he knew he would gain nothing from exile. It was he who decided to receive the Nobel Prize in Moscow from the Swedish ambassador. When he left Russia in February 1974, Solzhenitsyn was expelled, meaning he went into exile by force. This is what I call the best dissidence – that of the one who stays and fights until the end. But only until a final moment, when, as in Kadare’s case, that symbolic departure becomes more effective, turning into a political event. He also chose to stay in Albania. Nevertheless, among all cases and levels of dissidence, the most superior is that of the person who, in the situations we are discussing, remains in the homeland.

You also collaborated for a long time with Jusuf Vrioni. How did you know him?

Jusuf, whom I knew for 20 years, was more than just Ismail’s translator. He reminded me of a man who had the grace of nobles, regardless of his origin. Besides that, he knew French brilliantly, having lived in France even before the Second World War. This Western side of him was immediately noticeable – very elegant, very pleasant. We worked very well together. Conditioned by circumstances, Jusuf also translated the works of the head of state, Enver Hoxha, but he was no dissident (laughs).

In my opinion, every translator has their qualities and defects. In Jusuf Vrioni’s case, besides being a fine connoisseur of French, he had a tendency to expand phrases, providing longer sentences than the original to be more evocative. So, a bit too Proustian, I would say – demanding. But his translation conveyed a very good understanding of the thought and the phrase in general.

And now it is Tedi Papavrami, the young man who replaced Vrioni…?

In Tedi’s case, the problem is his young age. He does not have a consolidated knowledge of all the historical allusions contained in Kadare’s work. But he is doing very well. In short, I have liked his work, and I now have one of his translations in my hands.

Do you plan to publish other Albanian authors?

We have already published several. A book of prose by Migjeni, who can be considered an Albanian Rimbaud; an anthology of 26 Albanian writers from Albania and Kosovo; and a book by Bashkim Shehu. Besides these, two historical-political works: The Kosovo Issue by Ibrahim Rugova and The Albanian Issue by Rexhep Qosja. Meanwhile, we publish 2–3 books by Kadare a year. He has prepared a serial collection for publication in other publishing houses of several Albanian writers.

You came to totalitarian Albania and waited 14 years to land in democratic Albania? You are late…!

Yes, I am late, but there is something symbolic in this. It has to do with one of those idyllic memories of ours. On my last visit, I remember we left Tirana and headed for Durrës. There, on the sand, we had lunch. At that time, there were even more trees around. And when Ismail later tells me: “You know? I will have a house exactly where we had our last picnic!” “Very well,” I said, “When it’s ready, you will invite me for a holiday. And here we are.”/Memorie.al