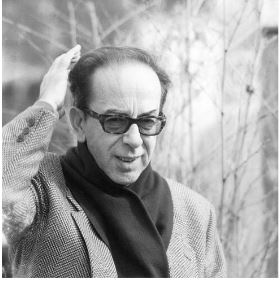

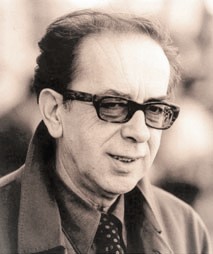

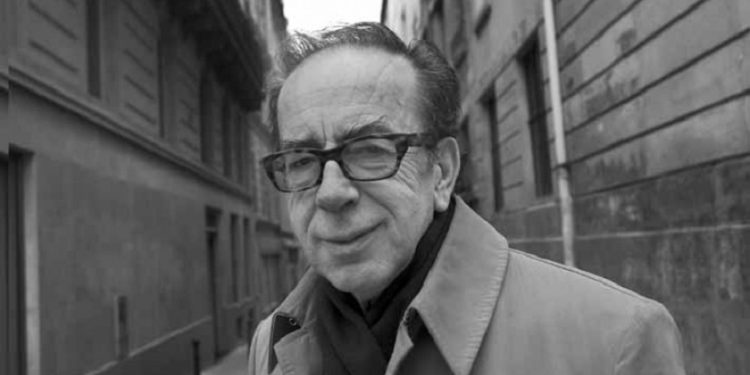

By Giovanni Maddalena*

Memorie.al/ My good Albanian – Armenian friend gifted me two books by Ismail Kadare, The Castle and The Unavoidable Dante – a drama about the Ottoman siege of an Albanian castle, and the history of Dante’s reception in Albania. In one of those life coincidences that I am sure the author would appreciate, I read the first book in English while in New York, and the second one in French, on the other side of the Adriatic, in the small, charming town of Termoli, where I have been living for several years. This intertwining of languages, cities, histories, and seas relates to Kadare’s captivating poetics conveyed to me by the two books, and perhaps, this is the sharpest resonance of the interest and longing that Kadare inspires. This article is dedicated to the reasons that brought about the birth of both. Let’s start with the longing.

I believe we are dealing with a double longing connected to histories and places. Kadare’s Dante is not an elaboration, it is not an essay, it is not an invention. It is a story of love and hatred, almost a passionate novel, about Dante and Albania. And the novel about the Albanian siege is again a story of love and hatred, again a passion, about the Ottoman Empire and Albania.

Pasolini used to say that every man writes the same book and always shoots the same film. There is much truth in this statement: each of us has his own core, a dominant tone, and the more this tone belongs to the universe, the more it manages to speak to everyone.

Kadare’s dominant tone, at least as I discovered it, a neophyte amazed by him, can be presented with the verses of the poet Rebora:

Oh, for man to become powerful

Unavoidable clarity of the truth

weave weave with your threads the fabric

and seal the history on cloth

but God writes destiny eternally:

thus blind and unlearned,

Between death and death,

I feel the low fugitive sound,

I, too, will have made you, I too.

It is always a potential difference between the smallness or suffering of life and the great destiny for which we feel we are created. But Kadare’s longing is love. It is not the arrogant infidelity of rationalist scholars for whom everything must be elaborated with the deductive use of reason, universal yet without belonging, for everyone, but unconnected to time. And it is not the cynicism or nihilism of one who thinks that fate does not exist.

Fate and the Particularity of Happiness

Kadare, in fact, always speaks of fate, whether he writes about Albania, Dante, or the Ottomans. It is the mystery of this fate from which this potential difference arises, upon which longing is layered: we feel we are created for happiness and for greatness, but these do not seem to be experienced in our history. We feel we are made for happiness, and we feel it above all through the places and persons we love.

In fact, happiness is always particular, tied to faces and images, to languages and customs. Happiness must pass through a certain kind of rock and a certain kind of language, and it must be linked to that beloved woman’s face, to that unfortunate, yet desired, son. Happiness for everyone else does not exist if it does not arise even for just one person – this is what I have been able to understand. And yet, this life always seems to postpone the moment in which greatness will come, happiness will be fulfilled.

Fulfillment seems impossible and sometimes desperately absent or utterly unattainable, just like Dante’s return to his Florence, just like the freedom of the Albanian language and people from the Ottomans or the communist power, just like the reunification of many lives broken by desperate emigration.

Life is meant to be happy, yet, often fate strikes the head anxiously and even threateningly. Or even worse, indifferent, just like the sky that Tursun Pasha gazes at before his desperate suicidal act. But Kadare does not think that the unintelligibility and pain caused by fate imply withdrawal from desires, nor from the toil that this desire carries: his characters, invented or historical, experience the desire for the fulfillment of this fate and the delay of its fulfillment. They experience it in different ways, Ottomans and Christians, but fate, whether far or near, is the goal of each.

For Kadare there is no doubt: within history, starting from that of his land, his people, his language. Kadare shows that a great poet is always “one living among the dead” and that the living one has a homeland, an image, and a language to which he belongs with his whole self. There is no Dante without Florence and Italian, and there is no Kadare without Albania.

It seems like a particular principle, while it is the beginning of a true universality, very different from the Enlightenment one. The more a person belongs to someone and something, and knows what the dominant love of his life is, the more he is capable of reading and understanding others, of living under any sky and in any condition: it is like when you know who you are fighting for and are not afraid to set off. Thus, Kadare’s fate is not the dark and general fate that dominates the philosophy of the Muslim soldiers who have surrounded the Albanian castle, but it is the ideal with which human freedom collaborates, even when in exile like poor Dante, even in the prison of Pound or Koliqi, and even in the hell of communism.

In fact, the ideal is delayed in its realization, and some places, like Albania, appear as witnesses to an endless martyrdom. But Kadare does not think that martyrdom is futile or despairing; he suffers sadness, but without despair. The intertwining of events is called history, and in the writing of fate in eternity is God. It is us humans who fight to make history, even when everything seems to end badly; but along the way, there are unexpected and fortunate turns, and in the end, as Kadare seems to say, all these sacrifices of ours may have a good meaning, the signs of which are those small, lucky turns.

The Interweaving of the Great and the Small

And here is where interest arises. The meaning of history, of the weaving and writing of fate, is played out in the heart of each person; it is a history of details, because in the details one sees greatness and smallness, the fight for destiny or surrender to it. The hearts of people from this perspective are all alike, regardless of language, lineage, or origin. History is played out in the fatalistic mind of Tursun Pasha, at the head of an endless army, in the dialogues of the nimble and frightened women of the harem, in the great Dante or the magnificent Kastriot, as well as in the prostitute who emigrated to Milan. Interest arises because the problem of the connection between life and the ideal – that is, fate – is the same for everyone, even for the last reader, wherever he may be.

Precisely this does not mean that readers are isolated units untouched by the issue. The understanding of an author like Dante or an event like the war with the Ottomans is still connected to a particular phenomenon, that of a people. Units build a people when there is a shared discussion of themes, questions, and the struggles to answer them. And the histories of peoples, as confirmed by the reception of Dante in Albanian lands, are also histories of friendship between peoples. All maritime peoples, and especially those of this sea, understand Ulysses’ return home, the tears of the emigrant or the exile, the sudden, overwhelming, and inexplicable death that only the sea and the mountain know how to deliver.

Kadare illuminates the brilliant proximity of folk tales – with their narratives and admonitions—to Dante’s perfect event about the three heavenly worlds, the deep sharing between the small and great questions that make up the life of each of us, who are chosen to fall into oblivion, and the verses that will forever immortalize the Dantesque characters. These last, in particular, perhaps represent the most captivating circumstance of the intertwining of fate with daily history, of the grandeur of our feeling and the smallness of our stories that Kadare lays out, mixing Dante’s phrases with our desolate voices as sailors: “What happens in Rome, war or peace? We set off from Durrës and drowned in the Strait of Otranto. Remember me who am Pia. Siena made me, Maremma unmade me. Light a candle for me in the Rmai cemetery. I gave up my spirit calling the name of Saint Mary.”

They are our small stories that build the great history, that tradition for which fighting for a castle or for the learning of a language is not useless even if the victory will not last; and conveying Dante’s verses is fundamental even if the benefit will not be seen. Like the eagles over the rocks of Albania, Kadare’s work discerns the distant horizon in the most minute and dark detail. But the horizon does not stand without the minutiae and vice versa. In the intertwining lies history, and in the writing of fate is God.

- Pia: The Divine Comedy, Purgatory, Canto V. Character from Siena, Pia de’ Tolomei, wife of Nello d’Inghirano dei Pannocchieschi, who kills her in mysterious circumstances in the castle of Pietra, in Maremma.

*The author of the article to be published in the newspaper L’Osservatore Romano is a Doctor of Science and a professor at the University of Molise.

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)