By Xhevat Ukshini

Memorie.al / “The fate of my people is also my fate”. This was the ethical and political maxim that guided Shtjefa Kurti in life. The Serbs persecuted him; the Albanians killed him, denying him even the right to have a grave on his land, for which he worked with his mind and heart, until the last moments of his life. The city of Ferizaj was formed in 1873, just a few years before the Albanian League of Perzerend, as the old Albanians used to call it, or Prizren, as we call it today, the modern Albanians, to this city, blurring it in this way, through Slavization of the name, its etymology.

Historical sources show us that in the space where the beautiful Prizren is located today, which in ancient times was known as Theranda, in the Middle Ages there was a settlement with the Latin name Peterzen where there were many churches dedicated to the first apostle of Christianity, Saint Peter. But the city of Ferizaj, being a new city, has no problem with the etymology of the name. His problems are other, but not less than the etymological ones.

They have to do with morality in general and with our national irresponsibility in particular, because this city that bears the name of an Albanian, who was also its last mayor under the Ottoman Empire, in the years 1908-1912, as if it doesn’t know what to do the difference between the contribution that comes from absolute patriotic devotion and other incidental circumstances related to his name.

However, Ferizaj does not have a street or square named after Feriz Shasivar, whose name the city bears. In fact, with its name, it is not associated with any special national contribution. The grave of Feriz Shasivari, with the Arabic inscription even after the Congress of Manastir, is located in the courtyard of the Mulla Veseli mosque. On the other hand, not even a street or square of this city bears the name of its guardian angel, that of Dom Shtjefën Kurti, who represented a completely different type of Albanian.

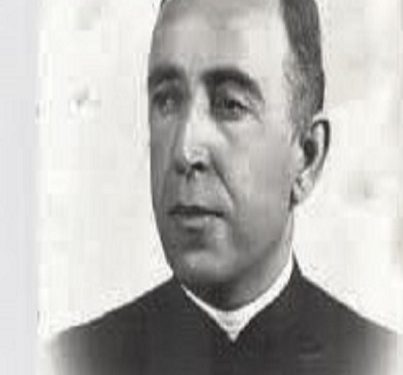

The famous Roman writer, Marcus Cicero, said that a lack of decision brings more harm than the wrong decision. In fact, in our case, it couldn’t be more wrong. Shtjefën Kurti raised his voice in defense of his people, who were oppressed and persecuted in royal Yugoslavia. “The fate of my people is also my fate.” This was the ethical and political maxim that guided Shtjefa Kurti in life, who was persecuted by the Serbs, but who was killed by the Albanians in 1971, denying him the right to a grave on his land, for which he worked until the moment end of life.

Shtjefën Kurti, together with the other two Albanian parishioners, did something that no other Albanian did, in that time of terror, terror and great loneliness. And yet, this guardian angel, unjustly, has somehow been forgotten by his native city, to which he has become a god at a time when others, for various reasons, have been silent or had no voice. . In 1930, Shtjefën Kurti, Luigj Gashi and Gjon Bisaku wrote a memorandum to the League of Nations with headquarters in Geneva, the predecessor of today’s United Nations Organization in New York, for the brutal violation of the national and human rights of Albanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

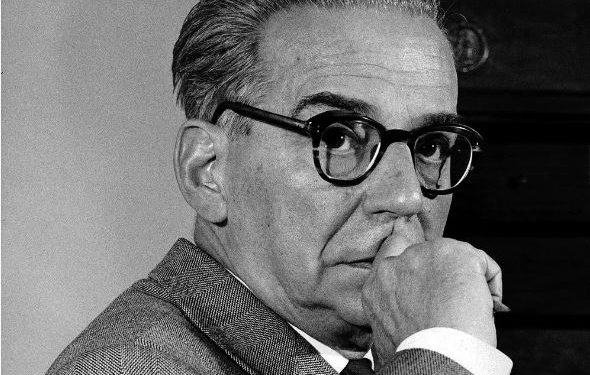

After the submission of this memorandum in Geneva, a tripartite commission was even appointed, consisting of diplomats from Norway, China and Spain, to verify the situation on the ground. The commission did not come to Kosovo to verify the situation, because Yugoslav diplomacy intervened. The State of Yugoslavia sent to the League of Nations as an ambassador, the later deputy foreign minister and Nobel laureate of Tito’s time, Ivo Andriç, who in a diplomatic way, completely neutralized the Albanian initiative.

The memorandum was archived at the League of Nations, it was put “ad-acta”. China and Spain still do not recognize Kosovo as a sovereign state, despite the fact that they had the privilege of recognizing its problems from the beginning. Norway, on the other hand, has diplomatically recognized the state of Kosovo and helps it in many ways. All three of these states recognize the Albanian problem of Kosovo since its inception, but their reaction to its existence, as we can see, has been quite different.

We know in the meantime, thanks to the Croatian historian Krezman, that Ivo Andriçi will later draft an essay on the migration of Albanians, which also predicted the destruction of the Albanian state. Ivo Andriç was rewarded for his effective work against Shtjefën Kurti, during the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, with the de facto post of Foreign Minister, although formally in the Government of Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Milan Stojadinović, he performed the work of Deputy Foreign Minister.

Andriçi was factually and formally the highest authority in that ministry, and during Tito’s time, he also received the “Nobel” prize for literature, thus enjoying the great support of the Yugoslav communist state.In a visit to Stockholm, Ivo Andriç said that; I have nothing to hide. Now we see that he has hidden a lot. Never, his Yugoslav state persecuted or punished the man who knew how to neutralize the memo of Dom Shtjefën Kurti. It was different with Shtjefën Kurti, who, as a reward for his national commitment, was shot by the Albanian state, which, after imprisoning him in 1946, sentenced him in 1947, for collaboration with British and American diplomats and finally, in the year 1971, with banal reasons, sentenced him to be shot, leaving him without a grave.

The formation of the city of Ferizaj, as is known, is connected with the railway that started from Thessaloniki and through Skopje, ended in Mitrovica. The construction of this railway brought with it the new settlement, which today is one of the largest and most developed cities in Kosovo.Feriz Shasivari is not its founder, as one might think at first glance, but the man who gave the name to the city, which the Turks began to call Ferizovik, the Serbs Ferizović, while the Albanians called him Ferizaj or, simply, Tasjan, a Turkish form this, for the French word “station”, to express disdain for Feriz Shasivar.

The Serbs, after the cession of the Albanian lands in 1913, named it “Uroševac”, i.e., the city of Uroshi. Even today, the city has two names that are officially known, in the country and in the world, one for the Albanians, the other for the Serbs. Today, the city center has the Mulla Veseli mosque with two minarets and the Serbian Orthodox church, side by side, within a courtyard. It is known that the building of the Serbian church was built on the property of the mosque. It is up to the scientific researchers to shed light on the situation of how a part of the mosque’s courtyard was “sold”, in order to later build a Serbian church there.

After 1999, the Serbian Church was guarded for several years by international police, and now it is guarded by Kosovar police, but it has no believers. Maybe there wasn’t even enough in the beginning, when it was built. The Serbs fled the city after the entry of NATO ground troops. The Serbian church stands in the center of the city, like a ghost that scares the Albanians, while a minaret has been added to the mosque, but also the coldness of the Albanians towards it, who increasingly see it as a political object. In the Serbian media, but also in the Albanian ones, praise has been expressed from time to time, for this extraordinary religious tolerance, because nowhere in the world, according to them, is there an Orthodox church and a mosque, within the same courtyard.

The truth actually has nothing to do with tolerance, but with fear, threats, blackmail and corruption. Both the mosque and the Serbian church are objects that were built in such turbulent times, when the city and our entire country were under the threat of the invaders’ weapons. The invaders, on the other hand, through these objects, wanted to alienate the political will of the natives. Neither the mosque nor the Serbian church would have ever been built, if the political disposition of the Albanian mass was taken into account, which wanted an Albanian state, and national signs, with which it would be possible to identify, but not symbols of their impotence, which emitted and transported the idea that they were foreigners in their own land.

The mosque was built after the breakup of the Albanian League of Prizren, and the Serbian church, after the Serbian occupation of Kosovo, so these cult objects, primarily for political reasons, always remain foreign to the majority of Albanian residents of Ferizaj. But in Ferizaj, these two cult objects are not the only ones. On the other side of the city, in an aerial line of no more than 700-800 meters, to the south, there is the “Guardian Angel” Catholic church, where today the parish priest is Don Mikel Sopi, who, as he says, is the successor in office i Dom Shtjefën Kurti. Dom Shtjefa Kurti used to mass in this church. Even this fact is known to very few residents of Ferizaj.

Who is Shtjefën Kurti, about whom Albanians should know everything, but in fact many of them know almost nothing?!His basic biographical data are as follows: He was born on December 24, 1898, in Ferizaj, in the city where he lived for only a quarter of a century. A few years ago, this city celebrated the 150th anniversary of its birth, and the mayor, Agim Aliu, declared Dom Shtjefën Kurtin the “Honour of the City”. Shtjefën Kurti was also a teacher of the Albanian School in Skopje and Ferizaj. He, together with Luigj Gashi and Gjon Bisak, drafted a memorandum for the League of Nations in Geneva in 1930, where he complained to this high international forum about the violation of the national and human rights of Albanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Shtjefën Kurti and his family fled to Albania at the beginning of 1930, that is, only a few months after the murder in Zym, of another Albanian priest, Shtjefën Gjeçov, with whom he had been in cooperation relations. After the submission of the memorandum in Geneva, he was appointed by the Vatican as a priest in a parish in Albania, where he would be imprisoned in 1946, as a man who cooperated with Western, British and American diplomats. In 1947, an Albanian state court would convict him of the charge; “for cooperation with the West”, with 20 years in prison. In 1963, he got out of prison and stayed for several months in Rrashbull in Durrës and later, he started working as a priest in the parish of Gurëz in Kurbin.

In 1971, he was again imprisoned and sentenced to death, being accused of; “espionage, sabotage and performance of religious rites”. In the meantime, a document was found in the archive of the Ministry of the Interior in Tirana, which proves that his body, after the shooting, was given to the Faculty of Medicine in Tirana, as a corpse for medical students. After a few years, Shtjefën Kurti’s corpse must have been buried in some unknown place. Nikolin Kurti, the nephew of Shtjefën Kurti or the son of the martyr’s brother, the brother who also spent several years in prison, has made great efforts to find his remains, but until today, he has not been able to find them find no sign of it.

The great American newspaper “The New York Times” also wrote about this unsuccessful search for the grave of the martyr and revivalist Shtjefën Kurti, while the former president of the American Congress Nancy Pelosi learned about Kurti’s patriotic and religious activity, while the Pope Francis declared him “Good” in 2016. In short, Shtjefën Kurti is our great reborn without a grave, like Jesus Christ and Gjergj Kastrioti.

The absence of a grave has a great symbolic load, because a man who does not have a grave cannot be said to be dead. Shtjefën Kurti was indeed shot, but he is not dead, because he lives in the hearts of Albanians, beyond the religious divisions of Albanians that exist today. The former professor of the High Technical School and the University of Ferizaj and also the University of Pristina, Dr. Kôle Kurti, says that; relative Kurti, has experienced a real ordeal in Royal and Communist Yugoslavia. However, as we can see, a part of the Kurti family has survived all these persecutions and punishments.

Not a few descendants of his relatives still live in the city. The core of the city center before, as we learn, consisted of the properties of the Kurti tribe, the very house of Shtjefën Kurti’s parents, Jak and Katrine Kurti, was not far from the old cinema of the city. “Many properties of the Kurts were expropriated by the Yugoslav communist state after 1945”, says Frank Kurti, who tells us that Gjon Serreqi himself, the son of his aunt, was related by blood to the Kurts which today is held by the main primary school of the city.

In conclusion, we can say about Shtjefa Kurti, that he did everything he could for his city and country, but as a reward, in the end he received bullets from the Albanian communist state, at a time when Ivo Andriç managed to become ‘de facto’ and the Foreign Minister of Yugoslavia, precisely because he was able to neutralize Shtjefën Kurti’s memorandum at the League of Nations in Geneva. Even today, his city and all of Kosovo have not shown the respect and honor that Shtjefa Kurti deserves.

However, he has defeated all his Albanian and non-Albanian enemies. The time has simply come to recognize the work of this Albanian renaissance, to recognize his moral and political triumph over the Albanian criminals who killed him and over the Nobelist Ivo Andriç, who once, stepping on the principles of universal morality, was victorious in the match with him in the international arena. Shtjefën Kurti’s triumph is at the same time our triumph, a decisive victory for the future of the state of Kosovo, but there are, unfortunately, still many Albanians who have not understood this. Memorie.al