Agron Tufa, Luljeta Lleshanaku

Memorie.al / “One day when I was working in the mine, two unaccompanied wagons came when I was picking out two others outside, and they hit my hand, which I have deformed even to this day. They stitched me up for life with clothespins, in the infirmary… I was howling like a dog from the pain… I will never forget those howls and that pain”, recalls Mirush Osmani, originally from the village of Kardhiq in Gjirokastra, a former political prisoner in the camps and the prisons of the dictatorial regime of Enver Hoxha and his successor, Ramiz Alia.

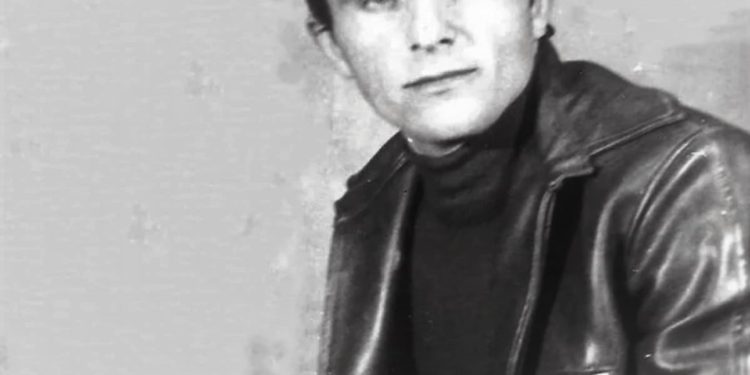

He was a young man with unparalleled self-confidence and many dreams of freedom. Somewhere in a deep village in Dropull of Gjirokastra, he had hatched his secret plan to break the bars of the dictatorship and gain freedom.

That’s how Mirush Osmani set out, on a winter night in December 1980, full of hope and faith… even with fear, but with conviction that the destination would be freedom.

He was only 20 years old with boyish courage, convinced that the irons of the dictatorship would never leave a mark on his hands; he headed towards the border…! But, bad luck would start exactly at the end of that journey, exactly when he encountered a group of pious choristers who, as soon as they confronted him, called him an “enemy of the people”.

They caught him and mercilessly handed him over to the border command, to take him straight to the investigator, where he would be sentenced to 10 years in prison. After many years, he tells us the marks that the dictatorship has left on him.

After the investigation and conviction, Mirush Osmani would be sent to Spaçi prison, where the real hell was the mine. There, where Mirushi also received the eternal mark on his hand, from an accident in the mine.

The testimony of Mirush Osmani

“One day when I was working in the mine, two unaccompanied wagons came while I was picking out two others outside, and they hit my hand, which I have disfigured to this day. They stitched me up for life with clothespins and thread, in the infirmary…!

I howled like a dog in pain. Even today I do not forget my screams. I remember the creaking needle. There was a nurse from Shijak, Isuf, I think his name was.

They left me without work for some time, but they didn’t even give me medicine for my hand, they didn’t even visit me or anything. The hand swelled and turned blue. At this time, a convict from Vlora, named Qemal Demiri, who, I will never forget who had served 15 years in prison and had another 10 or 15 years left, told me:

“I will write a letter to the Ministry of Health.” ‘O Qemal, what will we win’? – I told. “No, no,” he told me, “we will do it because these people intend to corrupt your hand.”

Qemali also wrote the letter, read it to me and we agreed to post it. Even if I wanted to write the letter myself, I couldn’t because my hand didn’t work. To feed, Çajupi, another friend, fed me with a spoon like a baby.

And when a team from the Ministry of Health came from Tirana to Spaç, I said to them: ‘You have sentenced me to prison or to disability’? They saw my hand and after a week it seems, they took me to Rrëshen.

There they did an x-ray of the hand and saw that all the bones in the hand were cracked. But when they took us prisoners for a medical examination in Rrëshen, the place was surrounded by soldiers, the hospital was surrounded, and for fear that we might escape.

Where the hell should we go?! And when they returned me to the camp, in Spaç, they put me directly in the dungeon. In the dungeon, in isolation. And this time they let me in alone, because I had complained.

Where such an order came from, I do not know. But with only one convenience this time: they brought me the bucket of warm water to hold in my hand. This was all the service they did to me. No more, no less.

When I came out again with a broken hand, they sent me to work. One Hajrulla Kruja took me to the brigade, which I will never forget. I was hired by Hajrulla Kruja, who must have been in his 50s at the time, and I was 21 years old.

It’s normal that he was sorry and did my job too. Even the comrades of my brigade made one more wagon to go in my name. I was also going with realized rate. For the command, it looked like I was doing them, but I wasn’t actually doing them.

I couldn’t grab anything by hand; I couldn’t fill the wagons anymore. I felt very much in debt to Hajrullai and the others, because they made ten wagons each for themselves and they were going to make them for me as well.

It was a daily chore and they did it just to save me from the wood and the dungeon. To this day, I am very grateful.

In these ups and downs, a group of us pick us up and take us from Spaçi to Qafë Bari.

In Qafe i Bari, the game changed. Kafa e Bari had a different command, with a different mentality; it was a command that was used to ordinary prisoners.

The fate of a man who weighed 50 kg, in Spaçi prison

If a man in the prison of Spaçi, or that of Qafë Bari, or even elsewhere, weighed 50 kg or less, he earned the right to refuse work in the mine.

This was the greatest luck for Mirush Osman, when he scored the record figure of 49 kg. At this point, he could refuse to work in the mine.

According to the laws of the Labor Party, it was like this: if you as a man were 50 kilograms or less in weight, the command did not force you to work in the mine.

Second, if you were over 55 or older, they had no right to put you in the mine. Outside the mine, in other jobs yes, they worked in this case, but not inside the mine.

And if a convict in Spaç, or even in any other prison, had a doctor’s report that did not allow him to enter the mine, he could not be forced to work in the mine.

I speak with the laws of the system itself. There came a time when I went 49 kg. Do you believe it?! I was like a corpse. A case similar to mine was Skender Tufa, for example. He was 50 kilos”, explains Mirush Osmani.

Violence in the Qafë Bari camp

“The brigade was taken by three policemen from a policeman who was in front; three policemen took it, and another three left it, that is, six policemen. Agron Qipllaka, Mirush Osmani (me) and Durim Qelibashi were on the list of the youth brigade that would be beaten, before going to work and after leaving work.

That is, we had the ration: before going to the cloakroom to change, we had to go to the boiler room, where six policemen were waiting for us with a hu in hand. Then we would go to work, leave work and back to the boiler, and eat wood for the second time. These were the decisions of Edmond Caja; he had us on the list.

In my brigade this happened; in the other brigades I don’t know how it went, but the youth brigade suffered the most of all.

Then an accident happened: because the police were looking for the norm at all costs and the front had no ore, the prisoner, in order to escape the madness, looked for the ore where his life was in danger.

In this way, two people were killed: Ilmi Çoçka from Lushnja and Dilaver Hysi from Vlora. Imagine a terrible scene: the wagon comes from the mine with Chochka split in two, the head separated from the body. Ilmi was about 48-50 years old.

His head was completely torn off and he was left hanging, and those criminals of the Grass Neck, to terrorize everyone else, had not even tried to cover him with a blanket at least.

They deliberately left him out, and his head was hanging from the outside of the wagon. I will never forget these scenes. They dug a hole, I don’t know where, and buried him.

Even the dog didn’t dig like that! Then came the death of Enver Hoxha, and on the occasion of the death of these prisoners, it seems as if some order was taken to release them a little. So, as if it was softening somehow…”!

After prison, towards the army

“I came out physically weak and anti-communist with deep convictions. I returned to Kardhiq to my parents, where I stayed for more than a month. The deserted mother seemed to me very gaunt and old after so many years. She treated me with all care, like a baby. Calculate: I was 50 kg. when I went home, and for a month and a half, I may have gained about 10 kg.

I will never forget that care; brought me back to life. They wanted to take me out to work, but I told them that I don’t come to work. I told them: “I’m not working because I’m waiting for an answer from the Executive Committee.” The family members were crying because they saw that I had made up my mind not to stay there with them. So I didn’t go to work; I stayed at home.

The mother had told the father that: “This boy will not work, and we will all pay him a pension”. She had me stop working at all. “Mom, I told her, I will work because I am my own master”! But the father was very, very ill and died a few years later.

After a month, instead of what I expected, I received a soldier’s letter. The letter fell into my mother’s hand, and together with my father, they did not know how to tell me, because it was difficult for me: I had just been released from prison, and they were taking me as a soldier. Mom was falling from side to side:

“What if, let’s face it, they take soldiers and take them to Durres or Vlora”? ‘I soldier?! I have passed the age and they have no right’ – I told him. Neyse, I don’t know who did it behind my back, but I had no other way but to join the army”, concludes his confession, Mirush Osmani. Memorie.al