Memorie.al / Following two previous editions, “Masakër në Buzëmadhe” (Massacre in Buzëmadhe) (1996 and 2015), this is the latest and most complete book by the scholar and writer Petrit Palushi. The author sheds light on the enigmatic event of 1944, the year in which 21 innocent civilians of Buzëmadhe were executed. Petrit Palushi’s book, “Masakër në Buzëmadhe,” is a tribute to the 21 victims of the massacre of September 26, 1944, a commemoration and bowing before the sacrifice of 16 women who were left widows and the beginning of life for 58 orphaned children. I have always been plagued and simultaneously provoked by fragmentariness and context, two notions I cannot manage to bypass! Only rereading makes a work’s achievement more complete. I begin to reread it…!

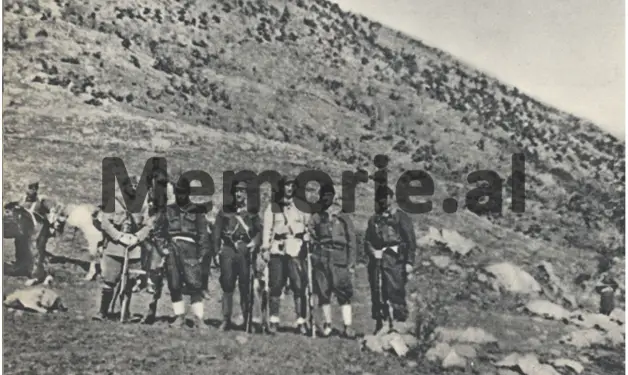

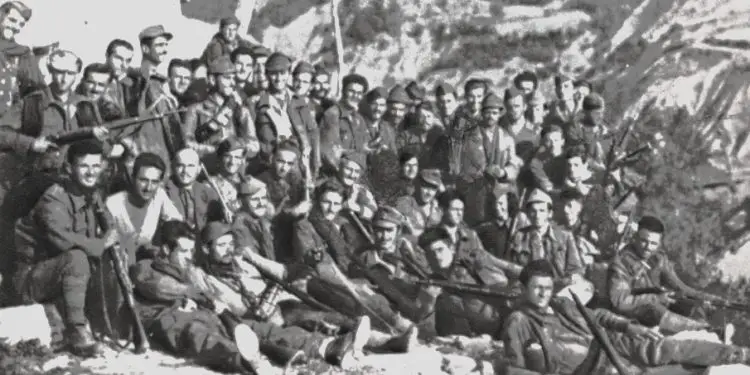

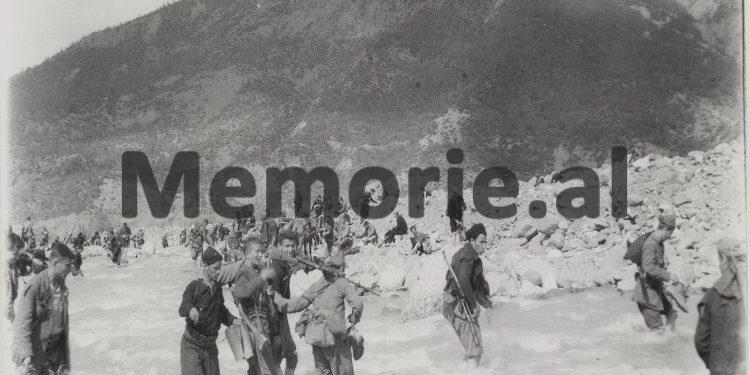

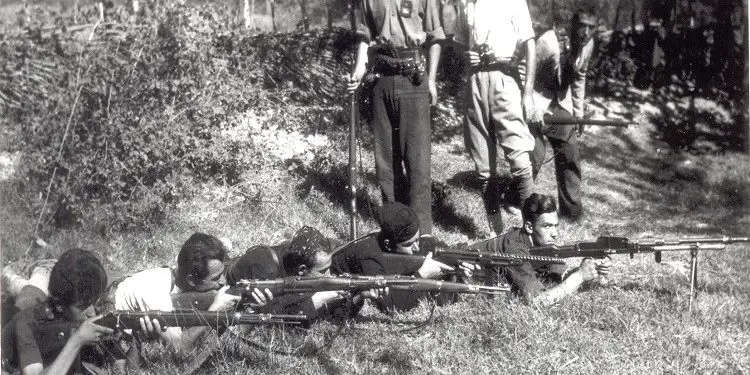

The book “Masakër në Buzëmadhe” (by author Petrit Palushi) addresses one of the most painful events on the eve of the end of World War II: the execution of 21 people in September 1944 at “Kroi i Bardhë” (The White Spring/Fountain) in Buzëmadhe. This work is a tribute to those victims and an illumination for the descendants of the 21 killed, while also being a remembrance and reflection on the horrors brought by Shefqet Peçi and his Brigade to Lumë.

The author of the monograph, Petrit Palushi, with a discourse of cinematic flow, brings to today’s readers a painful event that must be recalled in all the dimensions of that hot September midday, in the tragic inter-Albanian “conflict” in the village of Buzëmadhe. With this book, the author Petrit Palushi has fulfilled the mission of the writer and historian, which should be acknowledged with admiration and it is also an example of preserving memory. The book “Masakër në Buzëmadhe” is a work structured into 12 titled chapters, across three substantive parts.

The first part, which the author Petrit Palushi describes in the flow of time, is named after the book’s title itself, “Masakër në Buzëmadhe,” and recounts one of the most severe massacres that occurred in the region of Lumë, that of September 26, 1944, in which 21 people were killed. The book begins with a foreword or introduction in which the author compares the Buzëmadhe massacre to the tragedy “Macbeth.” Whereas nearly three and a half centuries earlier, King Duncan is killed as a guest by Macbeth in the latter’s house, the Fifth Partisan Brigade, led by Shefqet Peçi, kills its hosts by treachery – 21 inhabitants of the village of Buzëmadhe!

A comparative fragment, a discourse of epic proportions for a recollection that happens only once, leading to permanent pain: “… 340 years later, after Macbeth’s crime against King Duncan, a similar crime would be carried out in Buzëmadhe of Lumë against its inhabitants, but twenty-one times greater. The premeditated crime, planned twenty-four hours earlier, would take place in the strangely named place: ‘Kroi i Bardhë,’ right at the peak of the day of September 26, 1944. The scene at ‘Krue të Bardhë’ (White Spring), at first glance, is identical to the scene of Shakespeare’s tragedy ‘Macbeth.’

In the tragedy ‘Macbeth,’ King Duncan, as Macbeth’s guest, is killed by the latter – the host’s invitation is thus misused against the guest – while in the tragedy of Kroi i Bardhë, the guests in Buzëmadhe, i.e., the uninvited guests of the night of September 25, 1944, partisans of the Fifth Partisan Brigade, the next day, after eating breakfast, violate the most traditional rule of hospitality: they summon the men of Buzëmadhe village for a meeting, which, according to them, would be held at ‘Krue të Bardhë,’ and there, right in the presence of the Commander of the Fifth Partisan Brigade, they execute 21 of the hosts from the night before.

In short, despite the proximity, it is a different crime in the two tragedies. In Shakespeare’s fictional tragedy, it is the guest (King Duncan) who is killed by the host, the master of the house, while in the tragedy of ‘Kroi i Bardhë,’ it is precisely the guests who execute the masters of the houses where they spent the night. But the 21 inhabitants of Buzëmadhe were neither kings nor sons of kings…!”

While the “first part” covers the main “chapter” of the book, the other two “parts,” titled “Nga rrëfimet/1” (From the Testimonies/1) and “Nga rrëfimet/2” (From the Testimonies/2), contain the narratives: five authentic testimonies of event witnesses or surviving members (Hysen Sali Lala, Halim Sali Lala, Tahir Arif Lala, Shani Ramiz Lala, Shahe Riza Hoda-Cena) in one “part,” and in the other, the final “part,” the testimonies of those who were alongside the partisans are included (Nënoçe Osmani, Mezin Aliaj, Derro Deraj, and Elmaz Hasanmataj), according to the citation, mainly taken from Vangjel Kasapi’s book, “Mrekulli e natyrës, kështjellë e historisë” (A Miracle of Nature, A Castle of History), published in 1998.

A sudden solo trip from Prishtina to Kukës now marks an immediate closeness. Monday midday was ordinary. The weather began to change, and the spring rain had turned into a winter cold. The city on the roots of Gjallica, right at the corner of the confluence of the two rivers, Drini i Bardhë (White Drin) and Drini i Zi (Black Drin), arriving from “opposite” sides, was breathing, with a football match between two successful clubs from Tirana and Kukës. After the match, I met the well-known writer Petrit Palushi for the first time.

A gifted book, in today’s time, is a mission that can be poorly carried out, even forgotten! Older generations may view this phenomenon with doubt; nevertheless, we hope. “Buzëmadhe,” a name that is provocative. “Masakër në Buzëmadhe” is a book that you cannot stop reading until the end, leaving that mountainous village embedded in your memory, even before visiting, touching, or seeing it.

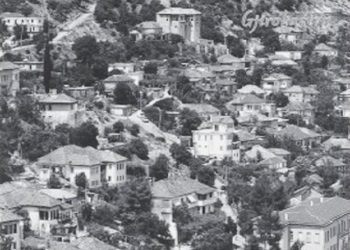

Between an artistic narrative and the material and documented historical data, the book “Masakër në Buzëmadhe” (which lacks necessary photographs for such publications, even of the village today) reveals an entire epoch of pain after a tragedy that was “untold” before! This is a book like a “mirror of the narrative” of an “unilluminated” event.

The author Petrit Palushi feels a responsibility toward himself as an obligation, not only to the victims but also to the future. He “seeks” help from the well-known Anglo-Irish writer Oscar Wilde, weaving endless thoughts: “…No man is rich enough to buy back his past” (O. Wilde), seems entirely appropriate for the story at ‘Krue të Bardhë,’ a history which, despite the foggy cover, despite that dark black fog rapidly and messily cast over it, now comes finely illuminated, without any omission…!”

Accuracy and truth shine painfully. “People recount the event as if it were a sudden action and have registered everything with precision,” the day of the massacre, the first days and nights after the massacre, the graves of the massacred according to the order, and those who recount the event are of different ages, but during their narratives, they are extremely precise, exceedingly precise, because the story, being told frequently and repeated every time, has strongly cemented itself in everyone’s memory!

The reasons for the doubts surrounding a letter as an enigmatic alibi are re-dimensioned with the exhaustive variation of the goal. “Firstly, it has often been repeated that the letter reached Shefqet Peçi late, and that, had it arrived earlier, the massacre would not have taken place. (The same thing was said after the execution of Ramize Gjebrea, as if such a letter… Ramize Gjebrea, who was executed on March 7, 1944, based on a partisan court decision signed by Shefqet Peçi, Hysni Kapo, Manush Myftiu, etc.)

Secondly, it is said that Shefqet Peçi took the letter and nervously tore it up; thus, he disregarded what was written in the letter, and the massacre was carried out. Thirdly, the imagination of people who were not properly informed often created the mindset that Enver Hoxha did not know about the crimes that might be committed and that, according to that mindset, he could never allow them…” All of this, because; “it was an attempt to create a state of continuous coma, so that the truth would not be unveiled and would sink into a dark past with no way out.”

And finally, the bleak atmosphere of almost half a century speaks the language of reality and the illumination of truth. “But with the change of the communist system, the events of September 1944 began to be revisited coolly, starting first by leafing through the era’s documents, which had been locked away in the archives until then, but also by taking as a basis the testimonies of the witnesses of the time, especially those upon whom the primitivism of the Fifth Assault Brigade’s partisan formation weighed heavily. Little by little, the bleak atmosphere was able to be re-dimensioned.”

The pain does not cease. It crosses the boundaries of legends. And of human life. The massacre survivor Hysen Sali Lala (in conversation with the author in September 1994, fifty years after the event at Kroi i Bardhë) says: “The sorrow of that day, I will only tell it to the Night of the Grave.” Halim Sali Lala, whose testimony is renewed over the years, expresses: “It is an event that is not easily forgotten. And there’s no way it can be forgotten!” (…) “I was saddened beyond words. I turned completely bitter.” (…) “I had no strength to walk or talk, I remained like a log in place.”

The dimensions of the crime were terrifyingly experienced. They were kept in the subconscious like a nightmare seeking release. But the crime exceeded every limit. Tahir Arif Lala: “…I never thought they would deceive the boys into going to ‘Kroi i Bardhë’ and commit the unthinkable upon them!” (…) “Even the women of Reçit couldn’t mourn as much as we mourned the people they killed!” (…) “…it was a regime that should never be recalled!” (…) “…he had committed the blackest mischief everywhere. He had spilled blood in Kosovo too; he had killed all innocent people!”

Witnesses recount the nightmare of those days in detail even half a century later. Shani Ramiz Lala: “I will tell you the words from the end to the top.” (…) “Remzi Islami brightened up…” Life as a sacrifice and the sudden event as destruction. Shahe Riza Hoda-Cena: “We were left four orphans. We grew up with great difficulty, because to grow up without a father is to grow up without having a master of the house!” (…) “That party did the unthinkable to us; it destroyed us, trampled upon us, and left us to swallow life with difficulty.”

Finally, the third “part” of the book, or the second appendix of testimonies, comes as a kind of repentance, but which essentially holds the “compactness” of a historical book, with data from the opposite side, “theirs,” as well. Nënoçe Osmani: “God punishes you for forgetting the Kukësian hospitality.” (…) “Once, when I had the chance to meet him, I mentioned Buzëmadhe, but he was silent as before a grief and no word came out of his mouth.”

A kind of repentance, a disequilibrium of dialogue between Mezin Aliaj and Hito Çako, 23 years after the massacre (1967)! A self-justification of conscience that amounted to no more than a monologue to oneself. Mezin Aliaj: “We didn’t talk any further, as we were both afraid of the bitter truth. The Kukësian people, as a counterbalance to Hysen’s commemoration, made the 21 martyrs-shehits (martyrs).” The former member of the Fifth Brigade, Derro Deraj from Brataj, said that “reality and honor do not dissolve in water.” And indeed, they come in the perfect “format” in Petrit Palushi’s book, “Masakër në Buzëmadhe.”

Analogies are necessary. Especially when dealing with a writer who addresses a historical fact that is not only documented but also has surviving participants. While, from a literary perspective, it is said that; “historicism cannot transform a 20th-century mind,” the writer Petrit Palushi, in the wake of successful achievements in illuminating the anathematized, even literary, period, manages to interweave the reality of a painful tragedy with an artistic language, thanks to the dedication and responsibility felt by a contemporary intellectual during the great transitions and “breaks” that occur in a society.

There are periods when time seems to move much faster than in another period. The dimensions of a loss are preserved in the most “dark” areas of consciousness. They are not forgotten. In the code of remembrance, as wisdom and warning of the people, it is said that even the thorn (as a mark or the most hated and hidden “object”) has revealed the killer! It may be delayed, but the crime is never completely erased from being known. / Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)