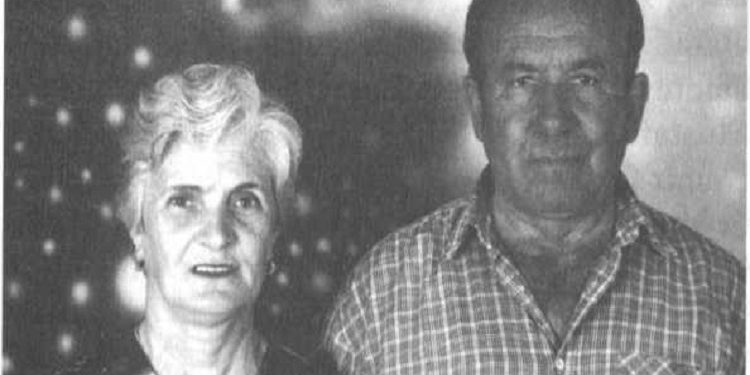

By Sofika Prifti Cara’s

Part eleven

To Forgive…!)

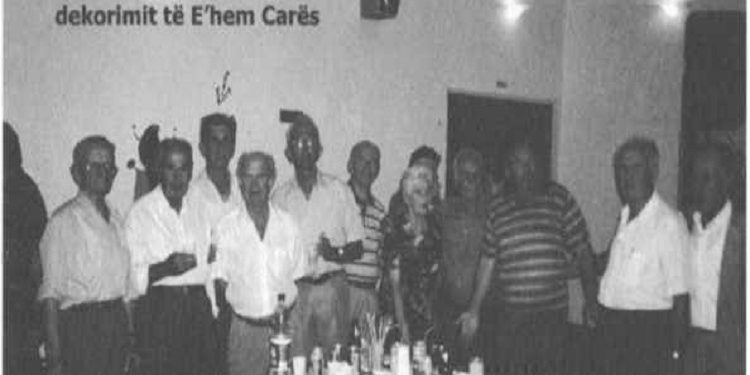

Memorie.al publishes excerpts from the book ‘To Forgive’, authored by Mrs. Sofika Prifti (Cara), published by the Institute for the Study of Communist Crimes and Consequences in Tirana, in which the author has described with detail and professional competence the history of one of the most well-known families, not only in the city of Kavajë but also beyond – the Cara clan. This family produced not only distinguished patriots who contributed to the national cause and the freedom of Albania, but also renowned intellectuals, graduated in the West, who later returned to the homeland, contributing in various fields of science and life. However, even though the descendants of the Cara clan dedicated their lives to the national cause, after the communists came to power at the end of 1944, they would be persecuted, imprisoned, and interned, and the fierce class warfare would follow them until 1990, when the collapse of the communist regime began.

Continues from the previous issue

THE DEATH OF AUNT SHEJA

As I wrote to you about Uncle Lami, he had two wives: Nënë Duda, who was Bardhi’s biological grandmother (and I mentioned a few things about Nënë Duda too). The second wife, Momë Sheja (Aunt Sheja), was from the Dedej clan of Kavajë. Momë Sheja (Aisha) was a special, rare woman, very gentle, wise, kind, hardworking, and very clean.

She was never annoyed, teaching us, the wives of her husband’s nephews, in every way. For our husbands, she was like a good mother. Momë Sheja loved her husband’s nephews and never separated them from her own son Rexhep’s four children.

When I got married, Uncle Lami had been dead for six or seven months, so I never knew him. On April 11, 1985, almost a month after my father’s death, Momë Sheja died, (on the same day as “uncle” Enver!) All four brothers were very close to Momë Sheja, as she had raised them herself, so her death saddened them immensely, and they cried with tears, like women.

Yet, even that day, they did not fail to provoke Xhevdet, who went out to buy some packets of cigarettes. One of the neighbors, who had built his house on Bardhi’s land (a corporal in the Internal Affairs Branch), were truly a “vigilant guard,” who always hypocritically told us: “You are good people!” He told Xhevdet on the street:

“Xhevdet! You must have cried a lot; your eyes are swollen because comrade Enver died! Even if you shed a river of tears, no one would believe you! We know what you have been through and how much you love him. Or are you afraid that I haven’t seen you crying and they might put you in jail?”

Xhevdet, calmly and prudently, replied: “Please, Ismail, leave me alone; I don’t have time to listen to your words, and I don’t know who has died. Momë Sheja died last night, and you know how she raised us!” The police informer was not flustered at all, but prolonged the conversation with a stinging remark:

“Wait, haven’t you heard? Didn’t you hear on the radio about the death of comrade Enver?! It’s not necessary for you to mourn him; all of Albania is mourning him, and the country is in black!”

When Xhevdet came home, he told us that the deceased, the country’s leader, had died…! Surprisingly, he grabbed the bottle of raki and started drinking. He never drank! I told him in a low voice:

“Have you forgotten that we are going to bury Momë? Don’t touch the deceased; she has been washed with abdest (ritual washing), and you have been drinking raki! What are you doing, Xhevdet? You have never drunk raki!” But Xhevdet answered thoughtfully:

“Raki is drunk for two reasons: for good or for bad. Today I have both reasons: for the great grief of Momë Sheja’s death, and for the joy of the dictator’s death. If Momë were alive, she would tell me: ‘Drink, boy, drink it all, I forgive you, because I found out who died…!’

There was only one thing I didn’t want: for his death not to happen on the same day as Momë Sheja’s!” We accompanied Momë Sheja, this rare woman, to her final resting place with great respect. Momë Sheja will remain unforgettable and alive in our hearts forever.

MY CHILDREN

My children grew up with many sacrifices and great deprivations. My son, Beni, finished the fourth grade with very good grades. He caught a severe flu, with a very high fever, 41-42 degrees, and for 15 days, it did not drop at all. This forced us to hospitalize him. But, strangely, in the hospital, we wrapped him in wet sheets; they had locked him in a room, and they wouldn’t let me in, because they “suspected” a bad disease!

In life, a person finds few good people; there are more bad ones. The head nurse there was named Marietta, from Elbasan. She felt very sorry for my son, and one day she told me subtly:

“I know your husband is in prison for politics, but what kind of mother are you?! Take your son and take him somewhere, don’t leave him until tomorrow! He is very sick, and it’s unknown what might happen to him. Today I did not give him the injection they told me to, but the other one will do it tomorrow…”! But what could I do in that situation?!

I had no means or power, but I left my son in the hands of the Fier doctors, who brought him to that degree of condition! Like any mother, I would give my life to save him, because it is natural that even an insect, no matter how small, will attack you if you touch its young one.

“Here is the key,” the kind-hearted nurse told me, “take it at night, when the shifts change! Before you take the boy, take the key from the door and bring it to me in the morning, at a quarter to seven, at the hospital bridge! When you give it to me, be careful that no one sees you, because they will expel me from the party! If they ask you, say you found the door open when the shifts changed…”!

I went home, told my brother-in-law, then we went at 11:00 p.m. and took the boy, but first we removed the key and went home. In the morning, I took it to Marietta, at the place she told me. At nine in the morning, the ambulance arrived with the doctor on duty and Marietta, who gave me the key. The doctor was demanding an explanation:

“Why did you take the boy?!” he shouted, and he was angry. He lectured me about the disease and the injection they would give the boy, which “allegedly” was for his own good. (I had heard that people had died from that injection!) Very upset, I told him:

“How dare you lecture me, when you brought my son to this condition?! With what morality, or with that of the white coat?!” I told him the names of those who had suffered like my son and died, and I told him that I brought my son there to be cured, not to be experimented on. “If he dies,” I said with tears in my eyes, “let him die at home, if the great God has written it.” Marietta winked at me; she didn’t speak at all.

“How did you open the door?!” the doctor asked me. I answered that I had found it open when the shifts had changed.

“Give us the boy; we have come to take him!” the doctor spoke to me in a commanding tone. But I objected:

“Go away; I’m not giving you my son!” “If you don’t,” he said, “the responsibility will fall on you! Then you will come with us to the director to sign that you took him forcibly yourself!”

“Go now; I will come to the hospital myself!” I told him. “I will sign when it is written that you did not cure my son, but you experimented, causing him to die!”

My brother-in-law spoke with one of his doctor cousins, and he told us to send the boy to Tirana as soon as possible. We went to Tirana. He had spoken with a Chinese doctor, one of those who were visiting Tirana. They were real specialists! They examined the boy, Beni, and said, revolted: “What have they done to him like this!? They have affected this child’s main nerve, which connects the brain?!”

We sent him two batches of injections, because the third one did not arrive, as we broke up with China at that time (!!) Perhaps my son would have died if he had been given that injection too! For me as a mother, I say that my son did not have the proper care. Perhaps because his father was in prison. May God take revenge! (With a mother’s heart, I wish the nurse Marietta a long life, health, and happiness in her family).

Irma, my daughter, finished the eighth grade, but they did not enroll her in the gymnasium. “There are no places,” they told us. Fier had only one gymnasium at the time. Her friends were enrolled; my Irma was not! She stayed at home with her grandmother for many years. I emphasize here that the grandmother had been ill with sclerosis for eight years, and Irma’s care for her was exemplary. The girl was 13 years old at the time.

At that tender age, a heavy burden fell on Irma; she would not only care for her grandmother but also wash clothes, clean the house, cook, receive whoever came to the house, etc. The soul of a mother grew up prematurely! All this effort came because I left for work at six in the morning and returned home at ten at night.

THE EXECUTION LISTS

Fier had many good people who minded their own business, but it also had many bad people. In that city, we seemed to have a curse. Imprisonment, internment, and persecutions were not enough; but the people and relevant structures of the communist government also took extreme measures: physical elimination for two people!

In our family, in 1988, two “bombs” burst: they had devilishly planned to sacrifice two Cara clan members, Bardhi and Sabriu. As was the habit of the red hydra, the dictator, who fed on human heads, after killing his own comrades, was not satisfied but wanted heads from our family too.

These lists, besides men, also included women, to be executed 10 by 10, in the mountains of Mallakastër. The ninth on the list was Bardhi, and the tenth was his brother, Sabriu. Since they failed with the “class struggle,” the people of the Enverist communist government used physical elimination to exert psychological terror on simple people. They wanted to dry up and wither the hearts of mothers and family members.

THE HEAVY STONE, IN ITS OWN PLACE

A popular proverb says: “The heavy stone, in its own place.” Forced by the great, repeated pressures, by imprisonments, by internments, and by the countless cleverly staged trials and denunciations in the neighborhood, but also by the risk of execution, we started thinking about how to somehow evade these cyclones. Our children were left without schooling, without getting married, because the class struggle was passed down from generation to generation.

We, from the husband’s house and also my parents’ house, seemed to have been affected by the disease of leprosy, and everyone avoided us out of fear. Thus, we discussed it as a family, and finally, we decided to leave Fier and settled in the birthplace of Bardhi and Xhevdet, in Kavajë. Xhevdet, fortunately, had found a military family, that of Llazar Turtulli, who had once been a responsible chief in the Kavajë Brigade, but who had died. In Kavajë, his wife lived with their two children. Both husband and wife were from Fier, so they wanted to come to Fier, near their people.

One day, Vangja, Llazar’s wife, offered us the exchange of houses and jobs with her son, as both mother and son worked in the NTAN (State Enterprise for Agricultural Machinery). She herself carried out all the necessary procedures: passport documentation, exchange of the house and job, without any problem. Even Xhevdet sought to come to Kavajë, and he told me:

“Sofi, in Kavajë, we have all our people; they will support us and will not let us perish! To tell the truth, until then, we did not know that the first two sons of the house had been placed on the execution list, without trial. But one friend had told Xhevdet one day: ‘Flee Fier as soon as possible, brother…!’ It’s a miracle how they were stopped without realizing their diabolical plan?! We were miraculously saved! At that time, the warm winds of democracy began to blow in our country.

On November 28, 1989, we came to live in Kavajë as a family. I truly felt regret, pain from this departure. Although I had been through hell in my own city, Fier, I felt bad about leaving. Everything was done for Xhevdet, who also made a great sacrifice for my children; he did not marry and remained a bachelor. He used to tell me:

“If I get married, I will be with my wife, and she will not love the children that my brother entrusted to me.” As soon as we arrived in Kavajë, Xhevdet told me, with childlike joy:

“My lungs got bigger here! Now I am breathing freely, because there in Fier, my breathing was blocked!” He seemed to have put on eagle wings and was flying free. “You saved years of my life; you agreed for me to come to Kavajë; you did not break your word!” he would tell me from time to time with gratitude, and I would tell him:

“Xhevdet, no, no, you deserve the best; no price can value you. You are a jewel of a man!”

When we came here, we were all unemployed, even the son, whom we had arranged to switch jobs with, was put to work late. Kavajë at that time administratively depended on Durrës. I went to the People’s Council of the neighborhood every time they had reception hours and asked for a job. But I came out empty-handed. After much effort, with friends and well-wishers, I got a work permit for the leather factory, where I had worked for 20 years.

THE FIRST ANTI-COMMUNIST DEMONSTRATIONS

In Kavajë, the anti-communist movements did not begin in 1990, but much earlier. The people of Kavajë had begun to express their dissatisfaction and revolt against that hated regime for some time. This had happened in the city’s enterprises and factories, where various governmental officials of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and his successor, Ramiz Alia, had been mocked and fled shamefully to Tirana. Then, leaflets began to be distributed in shops and the gymnasium, and anti-communist slogans were written on walls.

The party secretary, who had come from Durrës here for the issue of the slogans, a high-ranking official of Ramiz Alia’s government, was forced by the revolted people to step with his own shoes on the works of his teacher, Enver Hoxha! Many people were beaten on the streets, arrested, and tortured: they wanted to find the initiators of this movement, but they failed; on the contrary, they incited and inflamed the mass protests even more.

Such protests were made by men and women in the Paper, Glass, and Nail-Bolt factories, in the Textile Enterprise, and everywhere. In all of Kavajë, the “cauldron” was boiling. Not only had that, but the boys of Kavajë carried the torch of the anti-communist flame to other cities in the country: Durrës, Tirana, Shkodër, Lushnjë, Fier, Elbasan, etc. In Lushnjë, Daut Elmazi, Edi Segeri, Arian Gjoni, and their friends rallied the people of Lushnjë, and when they asked them: “Where are you from?”, they answered without fear: “We are from Kavajë!”

More than twenty boys from Kavajë, with their rallying cry, caused a large crowd of revolted people to gather on the boulevard of Durrës, shouting various anti-government slogans. Durrës began to buzz, and the same happened in Patos, Fier, Shkodër, and other cities. And behold, the flame of this movement, which started in Kavajë, covered the entire country, changing many things in Albania. The long-desired days arrived, when the people felt the “first flower buds” of democracy burst forth!

Little by little, these “buds” grew, and their fragrance spread everywhere, much awaited not only by the layer of political persecutees but by the entire, long-suffering people of Albania. The great fate of our family willed that this great historical event should find us in Kavajë. It took the Sunday of March 25, 1990, when the youth of Kavajë bravely rose, striking the first blow against the dictatorship, killing fear once and for all. That Sunday, the “Besa” team was playing football on its own field against “Partizani.”

The government sniffed out the danger threatening it like a dog; it clearly sensed the approach of collapse and prepared plans on how to act. It wanted to prolong its life; it tried to stay on its feet still. The dictatorship took many measures to frighten and urge all officials to be ready to prevent the outbreak of the hurricane, which started right in Kavajë.

All those days, urgent meetings were held in schools, enterprises, and agricultural cooperatives; police were seen everywhere on the streets; the goal was to restrain people and prevent them from going to watch that match. But the situation had slipped out of their hands, and they could do nothing but gnash their teeth and bite whoever they caught. That Sunday, especially in the afternoon hours, it seemed as if the whole city was invited to a wedding! Yes, it was a wedding, a nationwide wedding!

And that wedding had its dance floor on the green carpet of the stadium, where football would be played, and instead of cheering “Goal!” the shouts of the young people would be heard: “We want Albania like all of Europe!” “Enver – Hitler!” “Down with the dynasty!” “Freedom – Democracy!” “Down with Nexhmija!” etc.

The greenery was polluted by dozens of border dogs and by SAM-ists in frightening uniforms, and by police and plainclothes State Security agents. But the people of Kavajë could not be held back, because they had reached the point where they could not take it anymore! Dozens of Enver Hoxha’s works, hundreds of “Zëri i popullit” (Voice of the People) newspapers, were torn up and thrown onto the field, they were burned! The patriotic song roared in unison: “Come, gather here-here, together with us…!” Memorie.al