By Volodymyr Viatrovych

Memorie.al/The history of Ukraine under communist rule is similar to that of other post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe. However, unlike other countries of the former Eastern Bloc, Ukraine fell under totalitarian rule much earlier – not after World War II, but several decades prior. The most heinous crimes of the communist regime (mass killings, internments, the Holodomor) were committed before the outbreak of World War II. Ukraine became a “laboratory” for the communist regime, developing proven methods to suppress opponents and perfect the tools of a totalitarian state, which were later utilized in other countries “liberated” by the Red Army from Nazi occupation.

After the fall of the Ukrainian National Republic in 1921, communist rule arrived in Ukraine as a result of the Bolshevik Red Army’s occupation of most of the Ukrainian territory. While there were many Ukrainians among the communist activists, the establishment of the regime was only possible after the Bolshevik army, with Moscow’s support, occupied Ukraine. Anti-communist resistance was significant, and numerous uprisings continued until the end of the 1920s.

Ukrainization

To control the territory, the communists had to compromise with the Ukrainian National Movement. They introduced a policy of “Ukrainization”: the Ukrainian language became official in government institutions, and Ukrainian theaters and universities were opened. These favorable conditions resulted in a rebirth of Ukrainian culture and the emergence of a new generation of poets, writers, artists, and film and theater directors. A new economic policy declared by the communists temporarily allowed peasants to own land and develop their farms again. Ten years later, after the communists seized full power, a famine would destroy the countryside, and the reborn “intelligentsia” was executed or imprisoned in camps.

The Bolsheviks realized that cultural and economic concessions to rebellious Ukrainians could only be temporary. In the second half of the 1920s, after the final consolidation of the regime led by Joseph Stalin, a major offensive began against everything Ukrainian. This attack was called the “Soviet Genocide of Ukrainians” by the renowned lawyer Raphael Lemkin. This genocide consisted of the suppression (executions and imprisonments) of the intelligentsia and the abolition of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Furthermore, the genocide resulted in the mass extermination of Ukrainian peasants, who were the main pillar of Ukrainian national identity. The artificial famine brought about between 1932 and 1933 took the lives of millions (estimates vary from 4 to 7 million people). This heinous crime became known as the Holodomor (from the Ukrainian holod – hunger, and mor – death, or “Death by starvation”).

In the early 1930s, the collectivization of Ukrainian villages was completed, and residents were forced to work on collective farms. As a result of this policy, farmers and livestock breeders became completely dependent on government subsidies. Through mass deportation and suppression, the communists were able to get rid of the wealthy and independent landowners – the “kulaks.” This was a group that could have formed the basis of a national movement. But even after this repressive period, local uprisings against the Soviet Union continued. To end the resistance movement, the government decided to punish the farmers who appeared reluctant with hunger and deprivation.

Extreme Systematic Hunger

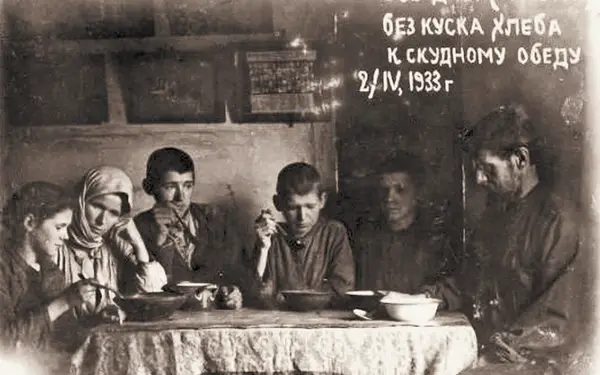

First, the government imposed unreasonably high grain delivery quotas on the peasants. The inability to meet these quotas was labeled as sabotage and resistance to the government. Then forced requisitions began, for which special brigades were sent to the villages. They confiscated all the grain they could find. The government violently punished anyone who tried to hide grain, which was declared government property.

In August 1932, a special law was passed, which became known as the “Law of Five Ears of Grain.” Violators of this law were punished with imprisonment or even execution for the so-called “plunder of socialist property.” In reality, it was an attempt to prevent people from keeping grain for themselves, so that not a single kernel of grain could be found after the harvest, let alone enough for a meal. Another method to burden the farmers was the introduction of so-called “natural fines”: farmers who did not meet the expected grain quotas had all their food confiscated. Entire villages were held responsible for “sabotage.” These villages were then placed on so-called “blacklists.” Such villages were completely isolated from the outside world, and all deliveries of goods and supplies were banned. In the end, the entire Ukrainian territory was transformed into a “hunger ghetto,” the borders of which were surrounded by an army that prevented starving people from escaping.

Without food and with no possibility of leaving the area, millions died of hunger. Entire villages were wiped out. Dead farmers were buried in large pits near their villages because there were too many dead to bury individually. Sometimes people were even buried alive because those collecting the corpses were so weak they could not travel twice to the same place.

This tragic death of millions of Ukrainians was long hidden from the world. It was forbidden to speak of the hunger in Ukraine. Censored newspapers wrote of the great successes of the Soviets, and any news of the famine was considered anti-government propaganda, which was severely punished.

Some victims of the hunger were convinced that it was the result of criminal activity by local authorities and that they only needed to inform the central government to stop these crimes. People wrote letters to Stalin to “open the leader’s eyes” to the horrors of the famine. The communist power listened to such letter-writers very carefully and then arrested them.

However, the survivors of the Holodomor tried to preserve their memory and save it for their descendants. Mykola Bokan from the Chernihiv region took photographs of his family during those terrible years. A short time later, these photos became evidence in the lawsuit against him. As a result, he was sentenced to eight years in prison. Mykola Bokan never returned from the Gulag concentration camps and died in a foreign and distant land.

A Witness to the Horror

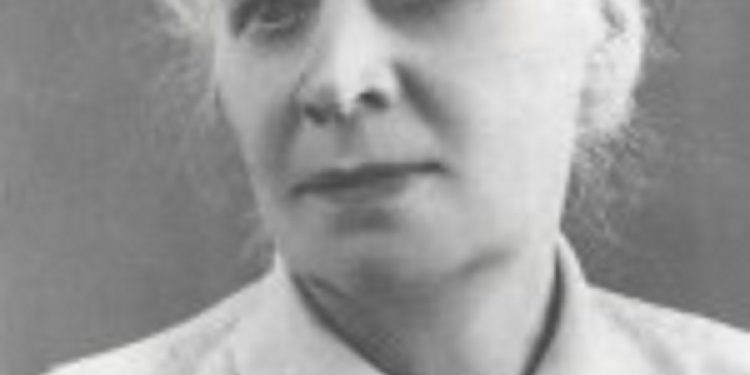

Oleksandra Radchenko was one of the millions of witnesses to the deaths from starvation. At the time, she worked as a teacher in the Kharkiv region. She had access to food ration supplies. As a result, she and her family managed to escape the hunger. But the “ration” she received from the state could not blind her to the horrors surrounding her. It was difficult to isolate her because, as a teacher, she had to look into the hungry eyes of her students and saw that their numbers were constantly decreasing. She knew that any attempt to provide information about the situation in Ukraine would mean her imprisonment, as well as the death of her children, who would have to fend for themselves in her absence. Oleksandra Radchenko understood the risks she was taking by entrusting her truth to her diary. She knew what awaited her if her diary was discovered.

Diary Entries:

- Tuesday, April 5, 1932: “Hunger, an artificial crisis, takes on monstrous proportions. Why do they take away the last crumbs of bread? No one understands. And they continue to take everything down to the last grain, seeing the results quite well. The children are tortured by hunger and by worms they have caught from eating raw beets, which will have to last them until the next harvest in four months. What will happen then??”

- Wednesday, April 6, 1932: “Sometimes an uncontrollable anger takes over me and I feel sick. I read about ‘rapid Soviet progress’ (reported in the communist newspaper Pravda), about the opening of the first blast furnace in Europe, about the completion of the dam at ‘Dniprostroy’ and many others. All this is fine, but what use is this progress compared to the bloated bellies of hunger and the deprivation of grown children? Hunger generally turns into anger and causes all our problems, everything imaginable. Crime develops very quickly… The thought of hungry children with bloated bellies haunts me and the anger grows…”

- Thursday, June 2, 1932: “Survival is difficult and the situation becomes more desperate. It is an unusual time, never seen before in history. Everyone suffers from malnutrition or hunger and an existence without money. Besides that, the impersonal is terrible and despairing.”

- Sunday, November 20, 1932: “The old man, who worked in the rabbit hutch, said he was ‘robbed by the authorities.’ This means everything was taken from him, like grains and vegetables. He was expropriated two years ago, almost a beggar, except he doesn’t beg. He is 70 years old, his wife 65. Their invalid daughter lives with them. And now, misery – the little they had left that could feed them until February has been taken from them.”

- Monday, January 9, 1933: “The horrors of hunger are spreading in Kharkiv. Children are being snatched and sausages made of human flesh are sold. The healthiest adults are being deceived and snatched by individuals allegedly selling shoes. The newspapers report this, while people are asked to stay calm as measures are being taken… but children continue to disappear.”

- Thursday, March 23, 1933: “Today I saw a group of suffering people. I returned home with heavy impressions. On the way to the village of Zarozhne, near the road in the field, we saw an old man; thin, in torn clothes and without boots. After he fell exhausted, he then froze to death, or simply died and someone took his boots. When we returned from the village, we saw him again. No one needed him…”

- “When we left Babka, we met a seven-year-old boy. My companion called him. However, the boy continued to walk unsteadily. He seemed not to hear us. When the horse approached him, I shouted and the boy turned off the road reluctantly. I couldn’t help but look at his face. The expression on his face made a terrible and unforgettable impression on me. It is likely that such an expression appears in their eyes when they know death is near. Yet they do not want to die. But this was a child! I could not control my feelings. Why? Why the children? I cried silently so my companion would not see. The thought that I could do nothing that millions of children are dying of hunger – the inevitable horror – led me to despair…”

- “A few days ago a rider came, with a bloated face and arms. He says his legs are heavy and that he is ready to die. ‘It is sad for the children,’ he says. ‘They do not understand. They are not to blame.'”

Oleksandra Radchenko and her three daughters, the youngest of whom was born in 1931, survived the Holodomor. They were untouched by the waves of suppression during the Great Terror between 1937 and 1938. However, they would have to endure much more misfortune.

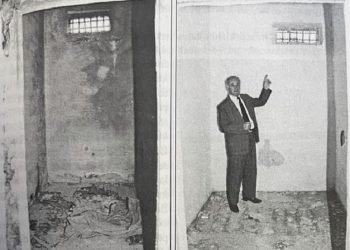

In 1940, the Radchenko family moved to Bukovyna, which had just been annexed to the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1941, they were caught up in the start of the German-Soviet War (World War II). Oleksandra and her husband Vasyl were arrested by the Romanian army, which occupied this part of Ukrainian territory as an ally of the Third Reich. They spent several weeks together in prison camps until they were released by her husband’s colleagues – forestry workers. After release from prison, Vasyl Radchenko continued to work as a forester.

False Hope

In the early days after the change of government, many of the local population, including Oleksandra Radchenko, believed in “German liberation from the communists.” For this reason, she told a German official, who had worked as a correspondent in his country, about her diaries. He suggested publishing them. German propaganda often used information about communist crimes (as was the case with the mass execution of tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war in the summer of 1941 and the discovery of their graves in Katyn). However, the diary about the Holodomor was not published by the new regime. Soon Radchenko realized that the new regime was no better than the previous one. For this reason, she wrote in her diary between 1941 and 1942 about the crimes of the Nazi regime.

The return of Ukraine to Soviet rule in 1944 resulted in another loss for the Radchenko family. Vasyl, Oleksandra’s husband, was sent to the front as a soldier in a penal battalion because he had served as a forester “under the Germans.” In 1945 the war ended. Before that time, their daughter Elida returned from Germany. In August, Vasyl Radchenko returned with a “Medal for Merit in Battle.” The Radchenkos were finally reunited.

But the good times were short, and the totalitarian regime intervened in their lives again. On July 7, 1945, an investigator from the regional office of the NKVD (Secret Police, later KGB) of Kamyanets-Podilsk signed an order for the arrest of Oleksandra Radchenko. While searching her apartment, they found seven of her diaries, covering the period between 1926 and 1943. The diaries became the main evidence in the charges against Radchenko. She was accused of “anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation.”

Her daughter Elida recalls that tragic moment in her family history: “Mama never hid her diaries. They found the box containing them. I was still able to hide five or six other notebooks under a pillow. When Mama was arrested, we started reading them and learned so much about the horrors of the Holodomor that we were afraid the whole family would be executed. Therefore, we burned the books…” But the information found in the notebooks seized by the NKVD was enough to convict the teacher.

The Investigation

The investigation lasted almost six months. Oleksandra immediately admitted that she was the author of the diaries. But this was not enough. The investigator tried to force her to admit that the entries were lies – that they were written to portray the Soviet regime in a bad light. “The result of the investigation was certain from the beginning,” she wrote in her complaint to the prosecutor a little later. “They threatened me with a long and drawn-out investigation if I didn’t sign a confession stating that I kept a diary with counter-revolutionary content since the early 1930s. Deep fear of prison, fear and concern for my ill health, were the reasons that pushed me to sign the confession.”

After the investigation concluded, the case went before the court in Proskuriv on December 14, 1945. In her final words before the court, Oleksandra Radchenko practically denied all the evidence included in the case, telling the judges:

“The main purpose of my notes was to dedicate them to my children. I wrote because after twenty years, children would not believe the violent methods used to build socialism. The Ukrainian people endured horrors between 1930 and 1933…”

Naturally, the judges did not listen to her, and the indictment stated: “Oleksandra Radchenko was hostile to the Soviet regime between 1930 and 1933 and wrote a diary with counter-revolutionary content, condemning the actions of the Communist Party, the organization of collective farms in the USSR, and describing the difficult living conditions of workers.” Despite the absurdity of the charge, it did not make the sentence any less real and cruel: 10 years in a Gulag concentration camp. Once in the camp, the former teacher continued her campaign for release, writing letters of complaint and protests; however, this did not change her fate.

Return to Ukraine

Oleksandra Radchenko returned to Ukraine in August 1955. She had served her entire prison sentence. Due to poor health, she lived in freedom for only ten more years. A few weeks before the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Soviet regime in 1991, Radchenko was “posthumously rehabilitated.” The Soviets admitted she had been wrongly imprisoned. Her diaries (unfortunately, not the complete set – three notebooks were burned during the investigation because they allegedly contained “no useful information”) were preserved in the KGB archives, and no one knew of their existence. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) inherited these archives. They contain the remaining diaries of Radchenko.

Only in 2001 were the archived documents discovered, including the diaries of the Holodomor atrocities. “I happened to hear on the radio that it was possible to see Oleksandra Radchenko’s archive documents,” recalls her daughter Elida, “and that they had been confiscated by the Secret Service. I was moved and started to cry. Mother’s time in prison had not been in vain and her work had not disappeared. She wrote the truth…” In 2007, excerpts from the diaries were published in the book Declassified Memory.

OLEKSANDRA RADCHENKO (1896-1965) worked most of her life as a teacher in Ukraine. She and her three children survived the starvation in the Holodomor between 1932 and 1933. She wrote about those times in her diary, documenting the horrors of what was in fact a deliberate starvation of the population. In August 1945, she was arrested and accused of propaganda against the Soviet Union. Her diary was presented as evidence during her trial. She was sentenced to 10 years in a communist concentration camp. Oleksandra returned to Ukraine in August 1955 after serving her full sentence. Due to poor health, she lived freely for only ten years. Memorie.al

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)