By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part three

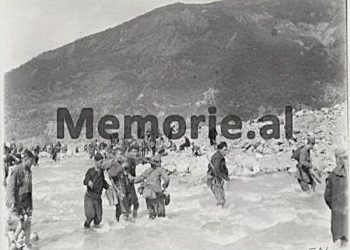

Memorie.al / I were born on 23.12.1951, in a black month of a time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the brutish investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Branch of Internal Affairs in Shkodër; they split my head, blinded one of my eyes, deafened one of my ears, after they broke several of my ribs, half of my molars, and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the pathetic Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After my sentence was halved because I was still a minor, a sixteen-year-old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the Reps political camp, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the Revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we claim to have. But on October 23, 2013, the Director General of the “Renaissance” government sent order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for the termination of a police employee’s duty. Thus, Divine Providence became entangled with the neo-communist “Renaissance” Providence, and precisely on the 23rd, they replaced me, with nothing less than the former operative of the Burrel Prison State Security. What could be more telling than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

REPSI

(The Forced Labor Camp)

Memoir

At that moment, I was hanging onto the wooden ladder that served for climbing to the top bunk. Nevertheless, suspended there, I turned to the yellow-mustached man and asked:

“What’s your name?” At the very least, he deserved a thank you for the help he offered me. He turned to me, his previous smile still lingering on his face, and his twisted mustaches rose even higher, almost touching his ears.

“Karolin…! Karolin Shala!” he said, adding his last name.

“Thank you, Karolin!” I thanked him with all my heart.

“No need! I did what, in the future; it will be your turn to do. Good night!” He turned his back and left through the door, without looking back. This was lesson number one!

“Lesson number one!” I thought to myself, and I thanked him again in my mind, not so much for the help, as for the lesson that would serve me so well during my years in prison. In truth, my dear friend Karolin gave me the most valuable lesson: how to love and help people in need, without expecting a thank you.

Now, as I write these memories, my friend is no longer alive, but while he was, whenever I was in Durrës, I would stop, we would meet, and we would have a coffee, in respect of that first lesson of hospitality in difficult times. “May you rest in peace, my friend, may your pure soul find eternal peace beside Jesus Christ! Amen!”

I climbed to the second floor of that endless bed. Dazed, I collapsed onto my unpacked belongings. I looked around on both sides. From what I could see, the shack resembled a hangar. A type of structure, fixed on some wooden posts planted directly into the ground, covered inside and out with straw slabs. “Oh God, how will I get through this in this barrack?!”

Suddenly, the cement depot at the Vau i Dejës worksite appeared in my mind. Through the porousness of the straw sheets, the Dibra brigade leader, Bastri Nurçja, would eavesdrop on our third shift when we hid in some corner to get some sleep. As a professional spy, he would listen to everything we workers were saying without anyone noticing, and then he would act according to each person’s biography. The spies who watched us in Zadejë did the same thing. That’s why they built the barracks with straw slabs, or as Zef Shkodrani called them, “spy-barracks.”

“They might have called crazy, but by God, he was right! Fine, there, it was supposedly to uncover the ‘class’ enemy who was hindering the fulfillment of the five-year ‘plans,’ because they didn’t want the progress and prosperity of Socialist Albania, but here? Is it because everyone they’ve gathered here are enemies?! Or, in the end, do they deserve this treatment?!” I gave way to the scrambled thoughts bubbling in my brain.

“Brr-rr, so cold!” I tightened the corners of my canvas jacket, but still didn’t get warm. Drafts of air moved freely from one corner to the other. The icy currents that seeped through the straw holes beat against my back and the nape of my neck.

“Get dressed, man, or you’ll get pleurisy!” I thought I heard a whisper in my ear. But what else could I wear? I had already put on everything I had in the cells of Shkodra.

“What did you say?!”

Silence. No one spoke.

“Am I hearing things? No, man, no—you’re talking to yourself, brother!”

“Man, is you full, or are you a little bit crazy?”

The two elderly neighbors looked at me in the eye. It seemed that when they heard me talking to nothing, they took me for a madman. I didn’t move, but stayed hunched over as I was. Every time I remember that day (more precisely night) in the winter of November 1968, I always imagine a confused oddball (which was me) and a bunch of men who, equally confused, were looking at that dazed kid.

Naturally, the shack could not have been a hotel furnished to receive tourists, but a torture structure for every season. In winter, these inert materials would bring on the frostbite, while in summer; they would be like a furnace and would turn into a model reservoir for bed bugs and other parasites.

As I would see in the days to come, the shack resembled a wreck, covered with eternit that in the summer multiplied the sun’s heat and in the winter lowered the ambient temperatures even more. For a ceiling, they had tacked on some pressed paper fibers, which also conducted the outside temperatures, depending on the season. Inside that hangar, there was no talk of heating; the cold and the heat penetrated equally. The structure was about twenty-five meters long, about three meters high, and four and a half meters wide, with two ill-fitting wooden doors, one in the middle and the other at the end, on the northern edge, with two windows that faced the central terrace.

On both sides of the straw walls, they had lined up two-story beds made of beech planks, as long as the entire length of the shack and one meter and ninety centimeters wide. Between the two rows, there was a gap of sixty centimeters, where everyone passed, which was the corridor. To lay the mattress, they had calculated seventy centimeters of space, but even this limit was not fixed; it would increase or decrease, depending on the number of prisoners in the camp. The height of the first floor from the cement floor was twenty centimeters; the upper bed was separated from the lower by a height of one meter and forty centimeters, while the rest of the space belonged to the second floor.

It is understood that you could never stand up straight because you would either hit your head on the planks of the bed above you or hit the ceiling on the upper level. However, experience had taught the prisoners, just as it would later teach me, to perform every action bent in half. The most comfortable position was lying down or crouching on the bed. Every two meters, they had nailed a pair of wooden ladders, which served for climbing up and down to the upper floor.

The lighting was completed by two dim electric bulbs, which, hanging from the paper fiber ceiling, could not penetrate with their faint light the entire space of the shack.

“Open up your mattress, kid!”

“Who spoke?”

“No one!”

I half-rose. In the gap specially made for me, I laid out the mattress. Then I sat on it. Since they didn’t answer me, I remembered to take a look at the surroundings, to get a fix on who I would have to share my prison days and nights with.

Unknown faces surrounded me, shaved heads, aged, haggard, pale visages. The light and shadow from the lamp hanging from the fiber ceiling gave these faces a monstrous appearance. The formless silhouettes swayed within the frames of this four-cornered picture, as if in a crazy quarantine. On the rows of mattresses, below and above, on both floors or even in the seventy-centimeter space of the corridor, the shadows would confuse each other, like some tragic actor statues on Dantesque stages. The phantasmagorical game transcended human imagination.

I felt that I was rolling into the abyss of an unexplored world, where I was being forcibly pushed. Unprepared to face the change, moreover in this unimaginable situation, I had the impression that I would get lost in a tangled labyrinth, without direction or beginning, that I was wandering endlessly inside a dark alley with no way out. I don’t know why Theseus appeared to me, when he was attacking the Minotaur, with Ariadne’s thread in his hand?

“Oh God, but me? Unoriented, without any protection, without any thread? Irremediably lost in the labyrinth of the communists’ zig-zags?!”

The very idea that I would have to get through all those years in this earthly labyrinth-HELL crushed me. Then, the thought of how I would be able to adapt to these new actors, to this macabre stage where they were making me an involuntary participant, in the troupe of this absurd theater, and were giving me an unknown role to play, was indigestible and my imagination couldn’t grasp it.

I huddled in the corner where they had dumped me. The millstone of my deranged mind spun in a void. Until that moment, no one had spoken to me. Maybe they were giving me time to get used to the environment.

“Where are you from, boy?” I heard this voice come from my left side.

“From Berat!” After this instinctive answer, I remembered my neighbors.

“How long did they sentence you to, man?”

“Five years.”

“Good, let it be a thing of the past!”

“Thank you!” I answered mechanically, while thinking: “Man, what do they take me for? Am I sick or something?” but I didn’t say it.

“Don’t you worry, man? Five years, they pass in a flash!”

“What did you say, man?!”

“In the blink of an eye, they’ll fly by, my man!”

“Did I hear that right, or was I hearing things?!”

But the neighbor pulled me out of my daze:

“For five years here, you’re gonna learn as much as for fifty years outside!”

“Man, what is he talking about? Is he sane or has he gone mad?! Oh God! They lock you up inside, for no reason at all, for five years in a row, and he tells me they’ll pass in the blink of an eye! What nonsense! Why didn’t he ask me, for God’s sake, why I was sentenced! Nothing! I’m going to learn a lot! Balderdash, old man, balderdash! Why, old man, did they bring you here to learn? Fine, when you were young, but haven’t you learned yet at this age? No, old man, no, they didn’t bring me here to learn! If they were going to teach me like this, they would have left me outside with my peers, sent me to school, and this whole matter would have been over! You’re going to learn as much as for fifty years combined! Oh, man, what did you just tell me! Where can one learn here, old man? Unless they take away those two bits of sense that the investigation left me with!”

I was thinking all this, but I chose to shut my mouth. I stayed silent. Later I would realize what a fatal mistake I could have made if I had spoken up. Self-restraint had honored me! There, everyone was sentenced for nothing, or almost nothing, for only three articles: either for (imaginary) escapes abroad, or for (supposed) terrorism against high state personalities, or for agitation and propaganda (never committed) against the “magnificent” achievements of the socialist system, which, according to the communists, only we, the enemies of the people, didn’t want to accept. These were the political crimes! So they didn’t see a reason to ask me?

“Listen, kid, you’re a young man, prison is gonna be a great school for you!” he spoke, and he was carving something with a thin wire knife on a small piece of wood.

“As you say!” I said for no reason.

“It really is a school!” he continued to scrape on the wood, then added: “But, like in any school, there are good students and weak ones, so some fail, some pass, some get tens, and some get twos!” He blew away some fine wood shavings. “It depends on the person what they want to learn and what path they want to take.”

“I don’t understand?” I interrupted.

“Just like that, then, like I said, it depends on what you want to take away!”

“Uh-huh, hmm!”

“There are professors galore here, for goodness’ sake! For all subjects!” He blew on the fine shavings of the wood he was carving again, and then continued: “For paradise and for HELL, for light and for DARKNESS!” He emphasized these two words strongly. “In fact, I would add, they are all professors; it depends on you, whom you want to choose?” “I see, I see! You must be the Head Professor of Madness!”

This disjointed lecture stunned me even more. I took a second look, across the shack. As much as I could see, I noticed some frail, aged people, some yellowish and anemic venereals from diseases, and some ragged skeletons, like martyrs from starvation. But no one’s physique impressed me, much less that they were as my neighbor described them!

“Come on, old man, are these the professors?!” still unbelieving, something that was easily visible in my wide eyes, I said back:

“According to what you are saying (I called him a lunatic to myself), there are no teachers left outside?” He looked at me sideways, from under his eyebrows, without lifting his head from the wood he was carving.

“By God, no!”

“What did you say?!”

“I don’t know how to explain it to you, boy, you come in here a fool and you leave with an education! You enter without merit and you leave with a university degree! A professor and more than a professor!”

“It shows?” I replied with irony.

“It depends on what you want to see, the good or the bad! Because here you’ll come out either a devil or an angel, you’ll learn a trade, you have to, man!”

I no longer trusted my ears. I couldn’t make out what I was hearing. I didn’t know if the old man was serious or joking! I stayed silent. I was speechless! But I also didn’t know what to say to him! “Damn, he seems crazy, but he’s tangling me up in a ball of thoughts, the beginning of which I can’t find!” I started scratching my shaved head.

“Oh, Esheref, leave the boy alone, man, let him collect himself! You’ve made his mind into a mess with your nonsense! He’s tired from the journey, from the cell, from hunger; the prison-van has completely taken his breath away. Wait until he gets settled, then I’ll teach him everything in order!”

I turned to the right, towards the arm from which this voice came. The gentle timbre seemed to caress my ear. I had almost forgotten that, besides the old man who was carving wood, there were others in the shack. I watched the speaker carefully; he was skinny and sallow-skinned, with a gaunt face, with some deep pockmark scars, with the look of an ascetic, which brought to mind the spitting image of Jesus Christ, just as I had pictured him in the icons hanging on the church iconostases.

The tormented figure of the man they introduced to me as a priest looked at me from beneath his wrinkled forehead, with two bright eyes that radiated parental compassion. The light of those gentle eyes seemed to restore my wavering security. The yellowish old man lifted the pillow at the head of the bed and pulled out a faded bag, untied some kind of cord, opened the mouth, and with a cupped hand, held out something to me.

“Take them, my son, eat them! This is what we found!”

But I remained frozen. He noticed my hesitation, so he continued:

“I know you need even more, but, man, we are all needy here.”

I still hesitated.

“Come on; don’t turn me down, today you are in more trouble than the others!”

I didn’t want to take them, but the low, almost pleading tone and the determination with which that exhausted man spoke broke my resistance. I reached out my hand; a few crumbled flakes fell into my palm. My guts were gnawing at me; I was so hungry that I didn’t believe I would ever be full; nevertheless, I didn’t rush to put them in my mouth.

“Eat them, man, don’t be proud! – he urged me. “They’re nothing special, after all!” he added, and then fell silent, lowering his eyes as if he felt ashamed that he had offered me so little. When he saw me dazed, with my palm still outstretched, he hastened to say: “Eat them, my son! Today it is you; tomorrow others will be in your place! I am sure that soon it will be your turn too, to do this, with the unlucky ones who will end up here!”

I had not eaten anything all day. For the entire journey, they had given us neither bread nor water. The rattling journey had tired me out, my guts were tearing, I opened my mouth, and devoured those flakes without a fuss. How delicious! But the way that priest offered them made them even more flavorful. I wanted to thank him, but I couldn’t find the right words. The old man understood my embarrassment, turned to the opposite side, as if he was talking to his neighbor. In the meantime, I had swallowed the last flake, when Uncle Esheref offered me a piece of bread:

“Eat this crust too, boy! It’s dry bread, but we don’t have any food!”

“Thank you, but…!”

“Eat it, man, you’ve got young teeth!” He waved his hand as if to say: “Leave the thanks for later!”

Indeed, at that time my teeth were like pearls, strong and healthy, but the pole, the spiked boots of the police, and the sulfuric acid-laced water at Spaç would grind them to bits, beyond repair. I swallowed that piece of dry bread as well; dry, without any kind of dish. Still, I didn’t feel full. I was young, the long stay in the cells, where I never had a full stomach, had done its part. He also didn’t accept my thanks!

Anyway, in my heart, I thanked both old men for their care, even if it was a little ironic. This is how I met my bed mates. I could not have dreamed of a more beautiful acquaintance, even if it lacked romantic finesse.

Those crumbled flakes and that dry crust of bread tasted far better than the most exquisite dishes. Even the later menus in the most famous restaurants of Athens, Rome, Thessaloniki, etc., where fate would take me years later, would not give me the pleasure and the taste of those crumbs that my unforgettable old men offered me, in that time of gall, amid endless privations and sufferings, where a crust of bread was equal to a day of life.

Now, when I recall the humane gesture of these two good old men, two tears unconsciously fall. I pray to God that each of them may rest peacefully in the heavenly paradise, where their pure souls must surely have ascended. But who were they?

Vasillaq, or Father Vaska, as the Korça people called him, was a man with an ascetic face, bloodless and without flesh on his cheeks, tall and thin, dressed with style, winter and summer in a clean woolen suit; a jacket, knickerbocker trousers, and a vest, he reminded you of the old-time men with pocket watches, although a pocket watch was not allowed in prison./Memorie.al