Fatbardha Mulleti (Saraçi)

Part seventeen

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the book ‘Calvary of women in communist prisons’, by Fatbardha Mulleti Saraçi, (granddaughter of the famous former mayor of Tirana, Qazim Mulleti), whose family from 1944 until in 1991, he was persecuted by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, where Fatbardha’s father, Haki Mulleti, a former senior state administration official since the 1920s, was imprisoned and interned by his family, until died in the hospital of Tirana, poisoned by the State Security. In her book ‘The Calvary of Women in Communist Prisons’, which is the fruit of several years of work, the author has masterfully described the unknown stories of some of the Albanian women and girls who suffered in prisons and internments in the dictatorial regime of Enver Hoxha, started by her mother, Pertefe Mulleti, and many others.

In addition to the above, the author Fatbardha Mulleti Saraçi, in her book, has described some of the tragic stories of some well-known families, mainly from Northern Albania (but also from Central and Southern Albania) such as; Gjonmarkaj of Orosh of Mirdita, Dine, Dema, Kaloshi, Ndreu, of Dibra, Pervizët from Skuraj of Kurbin, Miraka of Puka, Kola of Mat, Bushati, Pipa, Dërguti, Serreqi, Naraçi, Saraçi, Marashi, Gurakuqi, Çoba, Malaj , Vata, Deda, Vuksani, Kaçaj, Luli, Sokoli, Mushani, etc., of Shkodra and Malsisë e Madhe, Kupi, Merlika, of Kruja, Kërçiku, Mulleti of Tirana, Staravecka of Skrapar, etc., which were persecuted and were massacred in the most barbaric way by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, parts of which will be published in the continuation of this cycle of articles by Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

Pervizi family

One of the families that have experienced internments and prisons from 1945 to 1991 is the family of General Prenk Perviz, who had been a general in the National Army. They were interned with their families.

Mrika Pervizi

– (Bulger 1860-Tepelena 1949)

She was born in 1860 in Bulger, in a patriotic family, which had contributed to the League of Prizren and the family towers were burned by the camps of Dervish Pasha in 1881.

She married Frrok Preng Perviz, with whom she had a son, Prenk Perviz, who was orphaned at the age of nine. Her son went to school at the “Mountain Dormitory” in Shkodra.

This venerable woman was not only the perpetuator of the Kurbin movement, but also a participant in it. In these circumstances he experienced the burning of the towers of the Previzajs named after Gjin Pjetrit, the leader who raised the flag, on the same day, November 28, 1912.

The wise, but also courageous, wise woman, was a real treasure trove of information about various events, historical and social life. Her son graduated from the war school in Italy, in Turin and Florence, and worked there as an inspector of Albanian students. Everywhere mother Mrikë accompanied her son. In the Albanian state, her son became a general of the Albanian Army.

When the communists took power, he was interned together with his son’s wife, Mrs. Prena, in May 1945 in Lezha, Berat and Tepelena, where he died in 1949 from suffering and illness, at the age of 90. Her body and bones were buried and reburied three times; her grave is not known where it is located.

All the accomplices who knew her spoke of her as a wise, faithful and courageous woman: “God did well”! -he always said in those difficult conditions of internment. I traveled to Lushnja and left for Savër, to visit my cousin. It was a meeting full of longing. In a small room, two makeshift plank beds, located on either side of the room, between them a dresser, some furniture and an exemplary cleanliness. Two families lived here: mother Hajrie with her son, Reshit Mulleti and mother Prena, with her son Genc Perviz.

I met Ms. Prena, who was a straight-skinned woman, dressed in black, to give the impression of a strong woman and who could hardly read her emotions. In the corner of the wall, on a small, triangular-shaped plank pedestal, mother Prena had placed a pipe. The curiosity of a high school girl made me ask her: – “Who made that pipe?”

The honorable lady gave me the pipe to see and in a sweet voice said to me:

– “My son Leka sent me, he worked it with his own hands, I have it in the Vlona camp, while I have my eldest son, Valentin in prison…”! As soon as I touched the pipe, I saw it; I noticed that Prometheus and the Eagle were carved in the front, eating the lungs. It was a work of art.

Those two nights I stayed in that small room, I was introduced to the stories of the internees, the sufferings they had experienced in the internment camps, especially in Tepelena, while I told them about Shkodra, the gymnasium, the studies, the books, for songs. I left to take with me a mountain of pain, stories full of suffering and everywhere I was followed by the stories of Genc, of the beloved Reshit, of the mothers, they lived in my heart and mind. The way back to Shkodra was accompanied by many tears, my tears of pain!

Prena Pervizi

(1900-1977)

Mrs. Prena Pervizi, the wife of General Prenk Pervizi, was born on January 1, 1900 in Rrëshen, in the family of the Bajraktars of Kthella. She married Prenk Perviz, in 1918 with whom she had three sons: Valentin, Genc and Lekë. The family lived in Kruja and Tirana, where Prenka was on duty as a district commander. From 1929-‘34 she followed her husband abroad to Paris, Italy (Turin and Florence), where Mr. Prenk graduated from the General Staff School in Turin and was an inspector of Albanian students in Italy.

She was a woman who worked for the emancipation of Albanian women. With the advent of communism in power, the family suffered persecution, which in November 1944, burned down their houses in Laç and Skuraj, as well as the confiscation of all property and possessions, along with the villa in Tirana.

In May 1945, he was interned together with his mother-in-law in Lezha, Berat and Tepelena, where his honored mother died in 1949. He was imprisoned in the castle of Porto-Palermo 1949-1950 and from 1951-’54 in Tepelena, where he joined his sons, Valentin of Lekë. Transferred to Lushnje, to the village of internment Plug. In 1955 he was separated from the boys, who isolated him in the camp of Radostina (Fier) and in Kuç of Vlora (1955-58).

In 1957 he joined his other son, Genc, after serving 10 years in prison and they settled in Savër and Gradisht. A reminder: One day in the castle of Porto-Palermo some officers of the Ministry of Interior come and when they are in front of it, they address:

– “How close is the sea! Maybe you hope that the general with submarines will not come to save you, who know how you will run to board the ship”! But the response they received was overwhelming. She replied:

– “If everyone leaves, or you force me, I will not play the country, gentlemen officers! Do you think that I will forsake my children and leave them in your hands? This is what I never do”!

The officers were amazed; they realized that they were dealing with a very noble and noble woman and mother, the most precious thing being her three sons. She despite all the suffering was lucky enough to become a grandmother, her sons formed families, eternity continues. Died April 15, 1977 in Plug, after major surgery. She should have been taken to hospital earlier, but neither the hospital sent her to the emergency ambulance, nor did the department take her with the car she had at her disposal. At the last moment, they barely loaded him in a tractor trailer.

According to surgeon Qiriako Nezho, if he had been brought earlier, a few hours and not a few days, he would have escaped. This case was identified to show how the internees were treated. How did the life of Mrs. Prena Pervizi’s three sons go?

Valentini graduated in Italy, at the Military Academy, became an officer in 1941, and was a cultured, patriotic boy. He was in love with a beautiful Italian, Gorician, whom he married, but unfortunately separated from socialist life in Albania. Valentin had to endure 47 years, prisons and internments, from Shkodra prison, in the camps of Berat, the castle of Porto-Palermo, Tepelena, Çorovoda, the Brick Factory in Tirana, Kuç of Vlora, the Plug and Gradihtëte sectors of Lushnja . The good Italian Goricia, kept her love in her heart and lived with the hope of meeting, but it was only reached on the threshold of the New Year 1992.

The train stopped, the tall but thin old man got off, stood at the Bologna station, until the last passenger left, but behold, there stood an old lady, and she longingly saw that man, alone. Luckily, they met after 47 years of separation, lived a few years of old age until May 14, 1999, when Valentine closed his eyes forever.

Genci completed his studies from primary school to the completion of the Aviation School in Forli (Italy) in 1943. His life in Albania was spent in prison, 10 years and 33 years of exile. He started a family, married an exiled girl, Albina Llesh Marashi, who was interned at the age of 10. Genci died of a serious illness in April 1989 and was buried in the village of Sopot. He left behind a woman with six children, who were born and raised in exile. Today they live in the USA.

Lek Pervizi, the youngest of the brothers, studied for eight years in Italy, with an artistic-literary profile. He returned to Albania in 1944. From a young age, he tried internment camps in: Porto-Palermo, Tepelena, Fier, Kuç of Vlora and Plug of Lushnja. She married an internee, Gjyljana, daughter of the fugitive, Nikolle Prek Malaj, who was interned together with her mother Zorka Malaj, at a young age, a four-month-old baby, in 1948, in Kuçova, Berat, Turan, Tepelena of Lushnje, where he grew up. Among the few children (babies) who escaped the diseases and sufferings of the Tepelena camp, he got the name “Beba”, with which all the internees called him.

From this marriage they have three sons. Living in Brussels (Belgium). Leka maintains ties with the homeland, runs the magazine “Kuq e Zi”, publishes books, makes translations, etc.

Here is how Lekë Pervizi describes his life in exile: The first internments were made for families who were declared “reactionary”, in May 1945, in Tirana, they were isolated in the new and old prison. Mass deportations began; the first refuge was the city of Berat, which became the center of all reactionary families, mainly in northern Albania, while the city of Kruja became the refuge of families in southern Albania.

All the families had their property confiscated, movable and immovable, and they were evicted from their homes, only with body clothes, and many families had their houses burned down, such as Gjon Markaj (in Mirdita), Marash (Shkodra), Dinet e Demët (Dibër), Kolat (Mat) etc. In Berat they were placed in the neighborhood “Kala”, later in “Mangalem”, “Murat Çelepias”.

The families were initially given 500 gr. corn bread, per day and were obliged to pay the rent of the house even though many of them lived in huts or huts. Three times a day he was appealed to the Home Office. From May 1945, the communist regime tried to humiliate them, using all means, such as inserting them into the opening of the city’s sewage canals. The internees sent them to work in agriculture and especially in the fight against locusts, in the planted fields.

Many families were forced to go to the mountains to make wood so that they could earn some money for their livelihood. In addition to the physical suffering and hunger, at that time, many interned families, experienced on their backs also numerous stresses from the lusts of the Security officers, who sought to shoot the young girls. None of the girls surrendered to the security guards, who imprisoned many of the young women.

Although the communist propaganda at that time used all means to humiliate the interned families, the people of Berat were very noble and within their means, helped us especially with food and clothing. In that period of suffering, there was great solidarity among the interned families. By the end of 1947, many families from Berat were sent to Kuçova, where the construction of the aviation field began. Families settled in Italian barracks and were given only dry bread to eat. After Kuçova, many families were sent to Valias in Tirana, to work in agriculture such as: Gjonmarkaj, Demët etc.

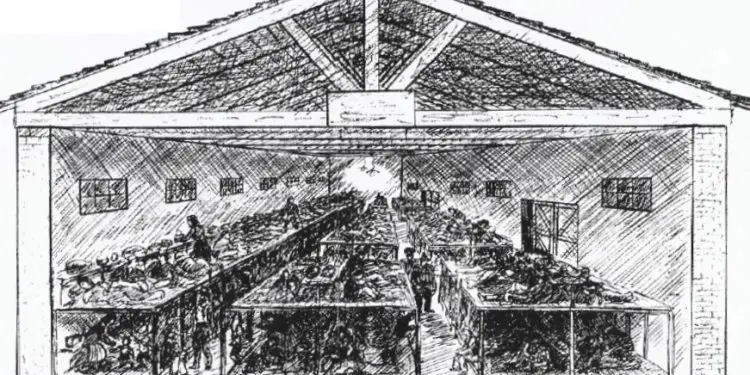

Enver Hoxha’s regime began sending internees to other cities as well. Towards the end of 1948 and the beginning of 1949, when Albania broke off relations with Yugoslavia, in the north of the country, mass escapes began. To curb that influx of refugees, the communist regime began deporting all members of the families living in the homeland. Elders, women, and especially children of all ages were spared. The communist state opened two more camps, in Turhan and Memaliaj of Tepelena. Those two camps were filled with interned families from northern Albania. Housing conditions were on the verge of misery and internees lived in primitive conditions. They were given only 500 gr. cornbread, nothing else.

At the time Bardhok Biba (communist ruler) was assassinated, the number of internees in both Tepelena camps reached 6,000. Due to the great lack of hygiene, epidemics of various diseases broke out there and people died en masse. The average death toll from those epidemics was seven per day. The greatest catastrophe occurred in August 1949, when 33 children died in the Turhan camp overnight. The children died of dysentery, there was no medical help and the cornbread was moldy. The horror of that night’s death added to the anxiety because it did not promise time to open graves for all the babies.

A woman from Vermoshi, Dukagjini, named Cukalina, lost her twin children, one in the morning and the other at dinner. They were the only men in the tribe, their mother killed herself the next day, and so did her sister-in-law. This tragedy caused a great commotion among the doctors of Gjirokastra and Tepelena, who had the courage and made it a problem in Tirana. The communist government of Enver Hoxha, was forced and sent there, a group of officers to see the situation and after that inspection, it was decided to close the camps of Turhan and Memaliaj. All the internees of those two camps were sent to the Tepelena camp, where they were placed in the Italian barracks, where there was water to drink. But even in the Tepelena camp, the internees were given only 650 gr. wheat bread, with a little worm soup that had only water. The deaths continued again.

Even there, the exiles could not escape the cold and hunger. They were sent to work in the forest for wood, manure, and to maintain and transport poles for construction. By the end of 1949, many exiles were sent to the Porto-Palermo camp, which had been used as a place of torture since Roman times. The internees were placed in the Castle and many of the internees were blinded by the darkness. The families interned in the Tepelena camp, stayed there, until the end of 1953, many of them were sent to different districts, for the construction of the buildings of the Internal Branch.

In 1954, the Tepelena camp was closed and all the families who were there were sent to several camps, which were opened in Myzeqe as sectors: Grabian, Çermë, Gradisht, Dushk, Plug, Savër, Xhazë etc. In 1954, some of the internees were sent to the Kuç camp in Kurvelesh, which had just opened at that time.

Among the 100 internees who were sent there, 60 of them had graduated from Western universities such as: Dom Mikel Koliqi, Ali Erebara, Ibrahim Sokoli, Nedim Kokona, Sami Kokolari and others. In 1958, this camp was closed and the internees were sent to the Myzeqe camps.

In those camps together with dozens of families, such as: Friends, Gjomarkaj, Çelët, Hoxhat, Bajraktars, Dinet, Demët, Ndretë and others, we stayed until 1990, but for the sake of truth, I want to say that in those camps there are still some of the interned families, who have nowhere to find another shelter.

This was the tragic fate of many noble families, which the communist regime declared “reactionary” and deported them for 45 years, in internment camps, which were open all over socialist Albania. In the family of the artist Lekë Pervizi, in Plug of Lushnja, Leonardi was born (year 1966), with the stamp “Enemy of the people”, the grandson of the general. At the age of 6, Leonard’s father notices in his son the tendencies for painting and he says: – “I started working with my son, on a program that I designed myself. The first thing I did to Leonard was a mud hut, with an area of 4 m2. for years, it would be his studio. Working systematically with him, albeit in inappropriate conditions, Leonardi manages to technically affirm the 16-year-old. He was prevented from continuing school, the reason would be defined “For class criteria”.

Only in 1989 was he given the right to study, but the Lushnja Executive Committee communicated it to him too late, after the competition at the Academy had ended. During the internment period, it was practiced in graphics, with ink paint. Color paintings have more possibilities of interpretation and to avoid it, Leonardi chose the graphics – says the father, Lek.

Why? – Because the communists knew about being politically convicted even with a painting, just as they had convicted for an unwritten poem, like the case of the poet Visar Zhiti. Leonardi left Albania in 1990, as a family. The Albanian boy was admitted to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, painting branch, in Brussels. After four years he graduated in this branch, and won the first prize, as the best graduate student of that academic year. Memorie.al