By Father Danel Gjeçaj

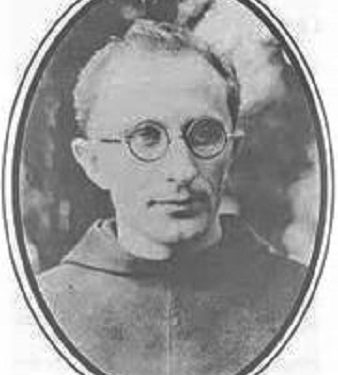

Memorie.al / Father Gjon Shllaku was born on July 27, 1907 in Shkodër, the son of Loro and Marë Ashta, at baptism they gave him the name Kolë. Still young, he entered the city’s Franciscan College, where he completed elementary and junior high school. On September 13, 1928, he granted eternal life, changing his name and being called John. He excelled at the “Illyricum” lyceum and the philosophy course at home, and for his higher studies he was sent to Holland, for Theology; as was the practice at the time to send them abroad. He was ordained a priest on March 15, 1931. He was sent by Provincial Father Mati Prennushi to continue his studies at the University of Louvain, first in the Science branch and then in History and Philosophy. He received his doctorate at the Sorbonne University in Paris (1936-1937) in philosophy, with the subject “The Actualism of Giovanni Gentile”. After his doctorate, he returned to his homeland, joining the teaching staff of the school that prepared him for university. A little while back, in addition to philosophy, he undertook to teach French lessons. With the Italian occupation of Albania, due to his anti-fascist stance, he left Yugoslavia and returned to his homeland on June 13, 1940, after many interventions. After the National-Liberation Front came to power, the authorities of the regime chose him together with Dom Ndre Zadeja, among the members of the Literature Committee of the Shkodër District Council. On January 14, 1945, the House of Art was established in Shkodër, where he was a conference speaker and later was elected a member of the presidency of the National Liberation Front for Shkodër Prefecture. In December 1945, after the arrest of some students of the Gymnasium of Shkodra, associated with papal seminarians, who had created the organization called “Albanian Union”, (who called on the people to rise up against the Slavic policy), in January they arrested and Father Gjon Shllakun, according to the accusation that he “led a terrorist group called “Black Hand” that would commit murders of people, related to Muslim and Orthodox religious leaders”. His trial took place in the “Rozafat” cinema together with the Jesuit priests P. Giovanni Fausti and P. Daniel Dajani, who were to be defended by the lawyer Kolë Dhimitri, while Padë Shllakun was defended by the lawyer Myzafer Pipa. On March 4, 1946, the clergy were shot in broad daylight, together with seminarian Mark Çuni, Gjelosh Lulashin and Qerim Sadiku. The document that we are publishing was prepared by Father Danilel Gjeçaj, (“Gallery of the Art of Martyrdom”), a Catholic priest who served in Italy before the 90s, after escaping from Albania immediately after the end of the war in 1944/

Meanwhile, the public trial, the so-called “People’s Trial”, was being prepared. Daily newspapers, radio, conferences and groups organized by the party were set in motion to create, in the people, the opinion that the imprisoned clerics were really leaders and responsible for an uprising, organized and directed by the Vatican to the detriment of Albania.

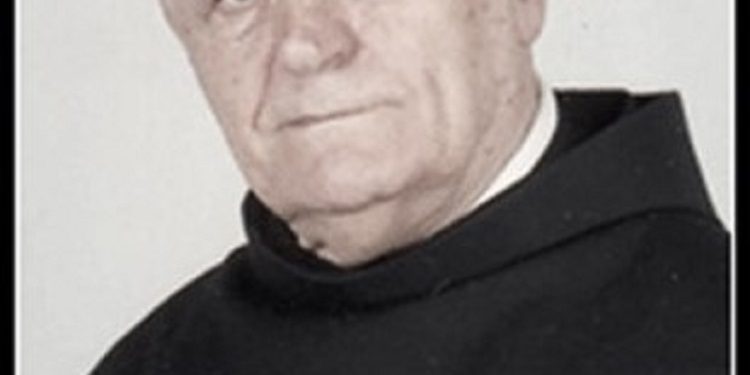

Father Gjoni, according to the prosecutor’s claim in the infamous indictment, was the leader and soul of this subversive plan. After him, according to the claim, Father Daniel Dajani and Father Giovanni Fausti lined up as vice-presidents, while seminarian Mark Çuni came as secretary. The accused, tired of the daily torture, either had to accept the accusations, fabricated by the party organs themselves, or remain silent. Defense was impossible. Every effort was cut off at the first words.

For the sake of formality alone, to give the court a legal appearance and to justify themselves before the outside world and the propaganda made, nominally private lawyers were accepted. For Father Gjon, the friars chose the courageous lawyer, Muzafer Pipa, former student of the Franciscan High School, disciple of many of the friar professors.

Muzaferi knew well the personality of Pater Gjon Shllaku and had that familiarity with him, which binds wise and righteous people at first meetings. Defense would cost him his life. He knew from the beginning that he could not do anything, in a country where there was no law or justice. That he could not protect the man, who had been condemned long before his guilt was proven.

Once, after the tragicomedy had been prepared in all details, the trial was opened. In the procession of the martyrs, tied to the fetters of the criminals, Pater Gjoni led the victims. After him came the two Jesuit priests, the seminarians and then the other civilians. The procession was escorted, apart from the defense police, also by groups organized by the communist youth, who, along the way, shouted and screamed like drunks, in chorus: “Bullet to the forehead! Bullet to the forehead!” and “Death to the clergy! Death to the clergy!”.

The professor-friar walked slowly, almost as if he could not trust his legs. He seemed to be very tired and faint; he had the face of a very suffering man, who has just got out of bed after a long illness. A wound was clearly visible on his forehead, like a fresh cut, not yet dry. The glasses barely fit on his nose. He changed tracks laboriously, bent over, as if lost in thought, almost as if he didn’t care at all about the noise and everything that happened around him.

In the improvised courtroom, the horror of that time awaited the military prosecutor, Aranit Çela, famous for his cruelty. A select audience, many party members, filled the hall. The accusations, drawn up from above, presented Pater Gjon as the ideologue, the organizer, the leader of the so-called “Albanian Union”.

After him, as helpers, came the Jesuit fathers, seminarians and other believers. Father Shllaku, according to the accusation, led the “Black Hand”, which would carry out assassinations throughout Albania, in close connection with the Vatican, through Father Faust, while in the country; he was connected with fugitive anti-communist groups. There were also hostile relations with the capitalist states, with the English and the Americans.

These were some of the accusations that blamed the friar, enough to deserve the death penalty, not only as an opponent of the regime, but also as a criminal and a person harmful to the people and the nation.

When the defense lawyer took the floor to reject the accusations, which he heard for the first time in that hall, the public and the jury burst into whistles and shouts: “Down with the traitors and their collaborators!”.

The death penalty, as we said above, was decided in advance. It did not come from the prosecutor, or from the whistles and roars of the indoctrinated people in the hall. The punishment for the best people of Shkodra came from Tirana. That’s how Shkodra was expected! That is why all the efforts of the Franciscans, where they could and where the day was, to save the life of the innocent brother, went in vain.

Father Dajani and Father Fausti, the seminarians Mark Çuni and Gjergj Bici, then the civilians Qerim Sadiku and Gjon Vata and several others were sentenced to death with Father Gjon. The sentence ended on February 22, 1946.

Who was Pater Gjon Shllaku? (Ports)

A simple friar with a great soul. A common lander with a high meander. A small face with a rare value. He did not see any greatness, as befits a friar – well, he attracted and made himself his own; he approached anyone for advice or for social and private problems. He knew how to behave in society and in any environment or social order; he preserved inviolable the dignity of the priest, the skill of the philosopher, the practicality of the sociologist, the wealth of an open and deep culture.

He had a strong sense of reflexes. He read a lot and memorized what he read with strange ease. He knew the modern philosophers and the works of the most famous authors of the time: Italian, French, and German. He was ready to discuss any scientific or literary issue, even though it was not his special branch. He valued quiet minds, but he did not despise a living person, an uneducated peasant or an unelegant orphan.

The face of an ordinary friar, who does not care about the duke’s appearance. On April 10, 1940, the most well-known albanologists of Italy: Tagliavini Carlo, Bartoli Matteo, Schirò Giuseppe Jr., Ercole Francesco and several others, visited Albania with the aim of forming an academy for Albanian studies. In the absence of Father Gjergji, then academician of Italy, Father Gjoni escorted his friends. Albanologists see the muse and the library.

They are left to enjoy. As a reward for the Franciscan activity in the lama of culture and to inherit their library, they ask for a list of books and works, which they would present to the government of Rome, to send to the Franciscans as a gift. Father John, prepare the list and take it to Rome. The Italian Ministry takes it into consideration and agrees. “Whoever drafted it – he answers – must have a very open culture and a prominent literary-daily taste: the marked works are also for us, therefore we cannot condemn you”.

Mindfulness reveals itself

Father Gjoni was born in Shkodër on July 27, 1907. His father, Lorja, and his mother, Maria Ashta, gave him the name Kola at baptism. Little Endè enter the Franciscan College of the city. There he completed primary and lower secondary school, where he became a symbol of quietness and courtesy.

He successfully completed the lyceum and the philosophy course in Atdhé. Later, like ours, he sent the Franciscan students abroad, precisely to the Netherlands. He studied theology there and was ordained a priest on March 15, 1931. In this year, he was sent by the then Provincial, Father Vinçenc Prennushi, later Bishop of Sapa (April 27, 1936) and Archbishop of Durrës (April 26, 1940), to prison in February 1949, in Louvain.

There, Pater Gjoni first followed the branch of sciences and later that of History and Philosophy, graduating with an excellent thesis in philosophy in 1936. Right after his doctorate, he returned to his hometown and immediately started teaching at gymnasium-lycé that had preparations for university.

Father Gjoni conveyed among the youth not only religious feelings, but also sounds culture and national feelings. Even for him, like other Ettan of the Northern Province, the binomial “Fé e Adhé” is ideal. Therefore, in 1939, when the fascist troops invaded the sacred land of the Motherland, because of the anti-fascist stance, he had to leave Yugoslavia.

Returned to the Motherland on June 13, 1940, after many interventions. Yes, many have never accepted the occupation, because occupation means violation, violence, injustice. Always coherent with the social principles of the Church, he worked back and forth, in silence, always in defense of basic human rights. The best part of the Shkodra youth was closely related to him.

When in our country materialistic ideas and principles, taken from Bolshevik Marxism and its agitators, begin to be planted, become and spread, to be disguised under the guise of patriotism and the liberation of the country, it is not clear the danger that threatens us, the Storm, which after a while would drown the Albanian people, including church and clergy, believers and regulars, peasants and citizens.

Father John stood out for his compelling logic and the clarity and power of his reasoning: modern in appearance, deep and immovable in his principles, concise and sure in his conclusions and consequences, neither opponents nor enemies could withstand him.

For now they were afraid: they were waiting for me to take the power in my hand and thus vent my anger and anger, which the righteous and the true bring to themselves in front of those who do not know the truth as much as they turn justice and goodness into a lie , slander, revenge, blood.

The conferences were accompanied by free discussion in the Franciscan premises of the “Djelmnia Antoniane”. Here Shllaku accepted with respect and respect, with Franciscan humanity, remarks and objections, clarifications and criticisms. He didn’t know how to insult or belittle me, belittle me or humiliate me, but he didn’t accept me to let go or compromise before the truth, keep silent before a mistake or bend before the threat of danger.

To the conferences, we should add the sermons held in the Church between Sundays and celebrations, in the month of May and between Shëna Ndout Tuesdays. Shllaku is not an orator in the traditional view of time; he remains a deep psychologist, a perfect conferencer, a clear and calm theologian and sociologist. Here, what made the people look at it with interest and interest was not the art of speaking, not even the external appearance: it was the thoughts, the landa, the reasoning, and the logic.

What distinguishes Father John in his priestly and Franciscan mission is his pen and writing. Here he gave the first evidence of a rare ability, of a unique talent. He wrote little, because the short time of his activity and the difficult circumstances, which he found himself in when he entered the ranks of writers, did not give him other opportunities.

I am more than sure that, had he had a long life and the normal state of the times and had he followed the natural development of the country, he would, without a doubt, have continued with honor the blessed tradition of the Franciscans in Albania, not only as a good writer, but also, and especially, as a teacher of national consciousness. Although in a different direction and under different conditions, Father Gjoni would have been one of the main elders of the Pantheon of the Elders, next to Leonard De Martino, Fishta, Gječov, Prennus, Harap, Bardhi, Palaj, Sirdan.

As the director in charge of “Hyllit i Drita”, the great magazine of the past, Father Gjoni gathers around himself the best feathers of the time. In the town of Fishtjan, where the platform of a free and progressive Albania was created, sat in the assembly, like the elders of the canon, the young writers, not only among Shllak’s brother, but also among civilians, Christians and no, but always worshipers of a God and loyal to an ideal.

He accepted modern and progressive ideas, but without avoiding the Christian principles of Albanian culture. He clothed the temporary in a new bridal garment, attractive to the generation in evolution. He was faithful to – and there was no way to leave – the nature of the magazine of the principle “moto”, which always characterized the pages of Hylli, without letting its rays shine in the sky of Albania: “Ubi Spiritus Domini, ibi libertas” – “Where the spirit of God is, there is freedom.”

This is the legacy, this last testament, that the father of Albanian letters, Father Gjergj Fishta, the Poet of the Nation, handed over to Father Gjon and, in Father Gjon, all the Franciscan youth, when the night before December (December 30, 1940) he was near to himself to command, with the last thread, Zâni, the Province, Albania, Hylli. There is a commandment, there is a holy trust – why holy is it among the trusts – that the earth holds, Father John guarded it with care and conscience, with competence and love until he sacrificed himself for this trust, and sealed that Faith with his blood, which he witnessed in life; that nation, that he loved with his heart, that country, that he honored with his deeds.

About ours, what we have said so far, Father John, here is the priest and brother. As a priest, he never forgot to live and act as a minister of God; as a friar, he kept Franciscan’s characteristic like the eyes of his forehead: his modesty, his love for the poor and simple, popularity, poverty. The eldest son of the Vobekt of Assisi, he was always small, even though under the dark, immodest shadow, he displayed spiritual greatness and mental height.

The feeling of doing it brought me back to Atdhé at the time of the fascist occupation; the feeling inspired him not to leave the country, as communism flooded. For this regular hearing and for this solitude, he died at the best age of his life. Memorie.al