From James Cameron

Part One

“Albania, the Last Marxist ‘Paradise’”

Published in “The Atlantic” magazine, 1963

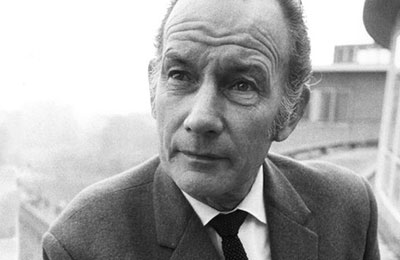

Memorie.al / Born in Scotland, educated in France and England, James Cameron had been a reporter for more than twenty-five years. As chief foreign correspondent for the London News Chronicle, he was one of the first Western observers to travel freely in Mao Testing’s Red China, and his account of what was happening inside that communist country was laid out in his book Red Mandarin, published in 1955. He now tells us how he managed to penetrate Albania.

For years, long before the outbreak of the conflict between the People’s Republic of Albania and the Soviet Union, which would split the Eastern communist world and make this small communist enclave a political phenomenon of the time, I had nurtured an erratic ambition to enter Albania. The impulse, I readily admit, was not entirely academic; a kind of “country-collecting” curiosity must have been involved. It happens that I have worked or at least been to almost every country in the world; it was my “trade” to travel.

But although I had moved through all the communist states, including China, Albania was the one that seemed impenetrable. I had periodically made representations to Albanian missions and consulates in Paris, Rome, Ankara, Sofia, etc., in distant legations, on dark streets. I always encountered either a complete refusal to discuss the matter or, more often, the blank, wooden face of a closed door with a dusty card explaining that the official was out for lunch. In any case, I had long “booked” Albania, and then suddenly I was there.

Several months ago, an advertisement from a travel agency in Cologne appeared in a West German newspaper, announcing an 18-day tour of Albania for a tourist group. There was nothing in it to suggest that it was addressed only to communists. Consequently, on the principle of trying something once, I sent an application to join this tour group, with the virtual certainty that it would be refused or, more likely, ignored.

But to my astonishment, it was immediately accepted, with a set of forms to be filled out, a request for a hundred-pound deposit, and the requirement that my passport be sent to Germany to be affixed with an Albanian visa. This, apparently, was to happen in East Berlin.

I did not feel in any way convinced to send my passport, upon which I depend for my living as a worker, its means, or my medical degree, into an unspecified German oblivion. However, these matters are more manageable now than they were before. A brief consultation at the relevant offices produced a second passport, which was dispatched on the proper route.

For weeks afterward, nothing happened. I put the matter out of my mind. Then, with that kind of manic abruptness that seems to characterize most things that happen to me, came an urgent message: the tour had finally been approved, and the group was ready. There seemed to be an inaugural flight by a Dutch line to Tirana. Would I go, immediately to Munich – the agency told me – where the tourist group would meet at the airport and where I would collect my passport and Albanian visa?

It seemed to me that there must be something either very naïve or very tricky about an agency that could cheerfully propose that a tourist travel from one country to another to pick up his passport! Nevertheless, I complied; if they were willing to ask no questions, so was I. So I came to Munich, and the pantomime began there.

I confess it had occurred to me that while my trick for penetrating Albania as part of a tourist group had been clever, it was not necessarily exclusive. I was prepared to discover that some other writer, journalist, or related tradesman was attached to this innocent party of visitors. I welcomed the possibility of a colleague and prepared to find them, if I could.

What I did not expect to find at our Munich meeting was this: among the seventeen of us, there was barely one who could claim to be, in any sense, a tourist. This discovery required no great talent, as by now the entire group apart from me was heavily loaded with technical equipment: 35-millimeter cameras, tripods, sound equipment, lights and lenses, wires and cables of great weight and complexity, and standing around with the weary vigilance of those who live by such matters.

Thus, when our “tourist group” finally arrived in Tirana some hours later, it resembled less the wide-eyed arrival of those bent on pleasure than the annual outing of some wild and capricious press club.

This visibly astonished the Albanians somewhat, though they adhered to comments with great composure. “You are tourists?” they said, as the passports disappeared one by one into a black leather satchel! Everyone immediately nodded, bristling with the suspicion of exposure. “Very good,” the official said with a rising tone of voice: “Welcome and we boarded the plane that would fly to Albania.

I don’t know what I expected. Most airports of the communist People’s Republics of the East were much the same in my experience. They had a common quality of unforgettable parsimony, are always at the end of long straight roads, and are constantly preoccupied with awaiting fraternal and friendly delegations. Tirana proposed every kind of change.

Here in the evening light was a scene of vexing beauty: a mantle of irregularly carved mountains, a purple frieze against the darkening blue, a long broad valley between olive-laden slopes that climbed the hill, a block of low buildings that could only politely be called an airport, yet confined and embedded in an abundance of roses. On the far side of the perimeter, I could see what appeared to be about two squadrons of years-old, already very familiar MiGs; between them and the runway, an old man with a turban on his head was freely grazing a flock of sheep.

The border control was of the usual People’s Democracy model, conducted with an unbearable calm, but strangely interrupted by a waiter with rolled-up shirt sleeves and a tray of raki in his hands. The female customs inspector accepted all the television technology calmly, and the owners, over whom there was a kind of depressive embarrassment, began to cheer up slightly. As it turned out, this was premature. The Albanians had not the slightest doubt about allowing the use of cameras; on the contrary, they had devised an inspiring technique of discipline. Instead of confiscating the equipment, they sealed it and insisted that the owners take it with them, swaying under the weight of the devices, which served only to remind them, if necessary, who was their boss.

My situation was very different, and my attitude tended (again, with reckless optimism) toward complacency. Alone among this false tourist company, I seemed to have made a great effort to resemble a tourist, at least by having nothing special with me – no typewriter, not even a notebook. However, it was my “innocent” currency that mostly captivated the customs lady, because, as it happened, it contained half a dozen paperbacks of various books – a novel or two, an essay book, and Tristram Shandy, which I had possessed, dragging it across the world for years and years against the day when it would push me into such lazy despair that I would actually read it. The customs lady took them out onto the counter and studied them with the angry suspicion of a scout unsure if she had been sent out with Henry Miller in a Bulgarian translation. She took them to a back room, where two other officials joined her, and for a while, I watched their heads together in confused disapproval. When the customs lady returned and closed my suitcase, the books were not in it, nor did I see them again.

We boarded a bus and drove to Tirana through the already fallen dusk. Along the bumpy road, we passed group after group of soldiers; young men in the old Soviet army uniforms, which were part of Russia’s seemingly less generous aid, back in the days when the two countries had very good relations with each other. On that first evening, it seemed that Albania was entirely populated by young soldiers, with caps jammed on their heads, gray jackets, and soft high boots. This impression would soon change; nevertheless, this small nation was clearly the most armed I think I had ever seen.

There was nothing surprising in this perception; since Albania’s entire past history has been one of almost uninterrupted turmoil and violence, a history of invasions and tyrannies, oppressions and uprisings, occupations and liberations, bitter exploitation and repeated revolutions. Here was a country steeped in tribal memories of endless war; add to this fact (since Albania’s population is still mainly Muslim) the exclusivity and attraction of Islam; overlaying the new doubts and disciplines of twentieth – century communism: it is no wonder I felt, as the faint lights of Tirana approached, that Albania is a difficult country to feel at home in.

The Albanians are among the most ancient peoples of Europe, the Illyrian tribes who somehow preserved their identity under the Greeks for six centuries B.C., who contrived to survive five hundred years of Roman occupation and another five hundred under the Byzantines, who chose these impossible highlands as their battlefield against the kingdom of Bulgaria. Albania w1as a bridgehead for repeated incursions toward the East of Europe, by the Normans in the eleventh century and the Venetians in the thirteenth. Even after the great Turkish conquest in 1478, the Albanians refused to settle down as good colonists and continued to be the greatest source of trouble in the Ottoman Empire for another four hundred and fifty years.

When the Austro-Hungarians, the French, and the Italians had fought themselves to a standstill over Albania in the First World War, there came the ambitious intervention of the tribal chief Zog, who declared himself first President, then King, in the 1920s. And who vanished with the wind in Mussolini’s Italian invasion, on the eve of the Easter holiday, in early April 1939.

In the inevitable progress of time, World War I produced Fascism, and the Second produced Communism. Licking the terrible wounds of years of guerrilla fighting and counting their losses- said to be 28,000 dead, 43,000 deported to concentration camps, 60,000 houses destroyed – the partisans who descended from the mountains of Albania declared their People’s Republic in 1946, under the protective arm of the Soviet Union. Thus went the “honeymoon” for fifteen years. And then had come the great divorce. Once again, the featherweight nation with the massive and furious pride was entirely alone.

The hotel in Tirana was off the main boulevard, behind a belt of evergreen. It was unexpectedly imposing. Like almost everything else of any pretension in the city, it had been handsomely built by the Italians in a broad style, but had long since acquired the joyless, antiseptic colorlessness of all the hotels of the communist Eastern People’s Democracies.

This is very difficult to define; it has to do with the dim lighting of powerless electric bulbs, a motionlessness of elevators, a dusty emptiness of display cases, a grayness of tablecloths, a lack of servants, and a surplus of unidentified functionaries in the shadows, who were clearly neither staff nor guests…!

These characteristics, in my experience, are shared by all communist country hotels and are explained by the simple fact that; befitting their function in societies where people circulate only with specific instructions, they have long since changed from hotels into institutions.

Nevertheless, the ‘Dajti’ Hotel in Tirana offered us a good show of hospitality, as much as the apparent lack of practice permitted. To implicitly deny the accounts of travelers that Albania is a country of unprecedented filth, starting from the floors of the hotel halls and rooms, which harbor microbes, I was given a large, desperate, but spotless room, with a very elaborate bathroom, complete with a bidet, surely a relic of the Italian occupation. The abundance of faucets and taps emitted a series of empty noises and groans, but no water. Out of a group of five wall switches, only one was functional, producing a thin, almost underwater light.

It was unfair to the tourist agency. To blame Albania, of all countries, for an insufficiency of tourists – even tourists as fake as us – was absurd. And yet, the peculiar fact was that Albania really influenced the belief that it was a tourist center. The gloomy lobby of the hotel was filled with leaflets and brochures depicting and extolling the virtues of its archaeological riches, its artistic culture, its social food, its ethnographic traditions, etc.

Some of them looked as if they had been there for centuries; others were undoubtedly new. They were printed in several languages: German, French, Russian, and Italian. To produce an English version was apparently pointless. Americans were neither sought nor allowed, and there had been no relationship with Britain since 1946, when Albania carelessly mined and blew up several British destroyers in the Corfu Channel.

What was the purpose of seeking foreign visitors while, at the same time, making it virtually impossible for anyone to enter the country?! For now, of course, there were no Russians either. The great rift between Albania and the Soviet Union may have been one of the strangest phenomena of recent times, expressing, as it did, ideological differences of great importance that transcended Tirana, but its visible effect on Albania was not delayed. Albania was a diverted branch from its “river,” and it appeared to be drying up.

The quarrel between Nikita Khrushchev and the head of communist Albania, former general Enver Hoxha, had begun slowly since 1959, and it reached a great wave in the summer of 1961. That the whole quarrel was, in fact, a development of the growing split between Russia and China, with Albania playing the role of a political shepherd, was already a fairly self-evident fact; thus, little Albania suddenly found itself upholding the banner of pure Marxism-Leninism against the corrupting wave of “Soviet revisionism” and “Titoist imperialism.”

It is said that the disagreement began when Khrushchev, on his official visit to Enver Hoxha, first became aware of Albania’s great and indeed extreme backwardness, even by Balkan standards, and then advised General Hoxha, in a fatherly manner, to abandon his wild and ambitious plans for the country’s industrialization. “Albania is an incorrigible peasant community,” Khrushchev is reputed to have observed; let it deal with growing tomatoes and olives, and do not suggest steel mills and fertilizer factories. It is easy to imagine Khrushchev saying this; it is also understandable that his urgings toward private peasant economy did not break the ice with the enraged General Hoxha.

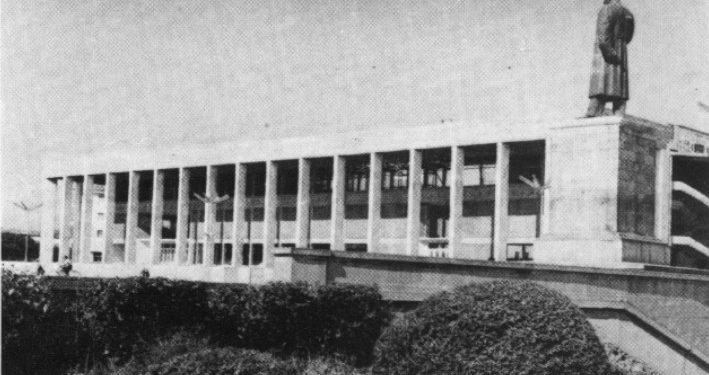

Anyway, the storm broke; Khrushchev denounced Albania at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, halted all Soviet aid, withdrew and canceled all financial credits, and also withdrew all technicians and specialists, leaving Albania as a dead country. The large and affluent new Soviet embassy in Tirana was halted halfway through construction and remains to this day exactly as the workers left it, without a roof.

The blow to Albania’s economy, such as it is, was certainly terrible, but far worse was the shock to its pride. Having no economic card up its sleeve to counterattack, Albania could only retaliate in a way that still seems somewhat comical: it maintained and nurtured the cult of Stalin.

In Moscow and Prague, in Sofia and Bucharest, statues of Stalin were carted away; in Tirana, on the contrary, the massive concrete images of the great man were not only rooted to the ground but were adorned with flowers. It was the perfect case where, in school textbooks, the man who had caused human bloodshed, Joseph Stalin, was adopted and presented as a national myth. There was something almost admirable in its senseless arrogance.

However, all this left Albania without a friend in the world, except the Chinese. The new diplomatic friendship between China and Albania had puzzled everyone, as it would hardly be possible to foresee two nations for whom an exclusive alliance would be more impossible, by temperament itself, and more physically difficult.

The largest nation on earth and one of the smallest; a large Oriental country of 650 million inhabitants and a Balkan province of 1.6 million inhabitants, separated not only by seven thousand miles but by every imaginable human, traditional, racial, and linguistic difference – it seemed entirely incomprehensible how they could even communicate with each other?

Admitting that the relationship was, in fact, a political cover, that Albania existed to be denounced by Russia and exalted by China, nevertheless, the Chinese had to do something about it, and if so, what?! The Chinese, apparently, had granted a $140 million credit. But what about China’s presence in Albania…? Memorie.al