By Gjergj Titani

Memorie.al / In the first part of this interview, published in the previous issue, Assembly, the only daughter of Pandi Kristos, told about her early youth full of contempt and insults from her friends and the disgust of the leaders of the Committee of the Union of the Labor Youth of Albania in the capital. The meetings with her father in prison and the deportation of her family from Tirana to Lushnja. The gloomy life of the family of the former close friend of Enver Hoxha and the hard work they did during the exile, in the Agricultural Farm of Çerma. The monstrous behavior of the powerful State Security and others. How Enver sent a letter to Nexhmije Hoxha, to continue his higher studies and the reactions after this letter, which added even more to the family’s misfortunes. Here is the first part of her shocking story.

Continues from last issue

Ms. Assembly, your father, Pandi Kristo, until what age did he work in Lushnja and what did he do after working hours?

The father in Lushnja worked until the age of 69, because he did not meet the seniority age, to receive the pension he was entitled to. The biggest paradox was that they did not know the time of the partisan war and anti-fascist activity! The Council of Ministers of the RPSH correctly sent all the appropriate materials of the working time that he had worked there, while the Central Committee of the RPSH, unjustly, did not send the documents of his activity to the Communist Group of Korça and in the Communist Party of Albania, so he was not given the time needed to retire, because the boring bureaucrats of this particular department, as I pointed out above, did not send him the official documents to prove the time of pension.

After working hours, the father usually listened to Radio Tirana and the news that it broadcast several times a day. He regularly read the newspaper “Voice of the People” and the new books that were published at that time, and it must be said that very high-quality books were published, from the classics of world literature such as: Leon Tolstoy, Victor Hugo, Balzac, Stendal, Mihail Shollohov and our Albanian writers. such as Lasgushi, Petro Marko, Mitrush Kuteli, Nonda Bulka, Migjeni, Çajupi, Naim Frashëri, Dhimitër Shuteriqi, Fatmir Gjata, Shefqet Musarai, Llazar Siliqi, Dritëro Agolli, Ismail Kadare, etc. Often we would comment together on the content of new books as well as express our own thoughts on these publications. But, I want to emphasize that in recent years, my father’s health did not allow him, because he had two myocardial infarctions.

How did the doctors in Lushnja and those in Tirana behave with your family, mainly with your mother and father, who were elderly and had quite a few health problems?

The doctors of Lushnja have been very careful professionally and very humane with the father, because, after leaving prison, he suffered two myocardial infarctions, once there in 1970 and the second time, in 1976. Cardiologist Vasil Kuli, (brother-in-law of Gjovalin Luka), who was interned in Zvrnec, who completed his university studies in Bulgaria and was married to a Bulgarian woman, has shown himself to be very careful and tireless, in relation to his father’s illnesses. , later also the mother’s. Vasil Lushnjari and Frano Shkjezi have also been attentive and have not distinguished whether the father was one of the most “dangerous” persecuted people in the country.

They treated the father very well professionally and with admirable professional competence, not only when he was sick, but also during medical convalescence, between two heart attacks, or exacerbation of the disease. Vasil Kuli, for example, was never lazy to often come home by bicycle, day or night, when it was necessary, so, even today when father and mother are no longer alive, I am very grateful to these doctors, for everything they have done, in order to ease their difficult state of health.

And your mother, Dhora, how did she react during the time when her family was interned at the Çerma farm? Did she know the top leaders of communism?

Before I talk about my mother’s attitude, when my father was convicted and the big troubles started, I would like to say a few words about who she was as a person, as a wife and as a mother. My mother was a shy woman, simple but not cowardly, she was balanced and never knew how to shout. In 1940, when Pandi was working together with one of the old members of the Communist Group of Korça, Peço Nedellin, who was my mother’s brother, they met and fell in love.

She was a seamstress, a beautiful and very charming girl, and that same year, she and Pandi got engaged. My mother, Dhora, took an active part in various anti-fascist activities and accompanied all the important illegal comrades who came to their house, to this important base of the Anti-Fascist National-Liberation War, and from there, she directed them to They were accommodated in other bases, where they had to be accommodated further.

She was not a party member, but all the leaders of LANÇ, starting with Enver Hoxha, Nako Spiru, Ramadan Çitaku, Vukmanovic Tempo with his wife Milica, Miladin Popovic, Dushan Mugosha, Ymer Dishnica, Naxhie Dume, Nexhmije Hoxha, etc. , have taken refuge in her and her brother’s house. This house was one of the main bases of LANÇ, in the district of Korça. After the liberation, my mother never became active in important social work, like many women of the Politburo members, and after the arrest of Pandi, she went to work for the first time, in her previous profession, as a dressmaker. Of course, she found it very difficult to relate to people and communicate freely with them.

She constantly lived under the tormenting anxiety of the punishment of her husband, whom she loved and respected immensely. She was very orderly, although many detractors expressed themselves with envious words: “How, this wife of Pandi Kristos did not lower her head once”?! My mother worked at NRG (Ready-to-Wear Garments Enterprise). In these difficult conditions, a young, beautiful woman could not think of staying alone and raising her child.

Therefore, Pandi’s sister and brother, Vangjelia and Koçoja, who sacrificed their youth and did not get married when they had the time, until I grew up, stayed very close to my mother. The father’s brother, Koço Kristo, first worked in the passport office of the Executive Committee of the city of Tirana, and then in the labor office. In collective meetings, they often criticized him and exposed him for constantly coming to Pandit to meet him in prison.

Once they warned him, threatening him not to go to prison with Pandi’s wife’s sister and me, the little child, who was looking forward to meeting his father. The uncle refused to deny his brother and as a result he was expelled from the party and transferred to NTLFZ (Local Trade Enterprise of Fruits and Vegetables), where at that time Sabri Godo worked as a director, who has treated his uncle very well. Afterwards, the uncle worked as a specialist in the bakeries, where the old communist, Ilo Budina, was in charge, a wonderful man and an old friend of my father, since the time of the Communist Group of Korça and one of the first communists to establish KPSH.

Uncle Ilua, as Pandi called him, the father of the three LANÇ veteran sons: Janaq, Sotir and Dhimosten Budina (Janaq and Sotir, were two honorable army colonels and two skilled engineers). Later, I remember, Koçoja worked at the Bread Factory, with one of Koçi Xoxes’s sons, Çlirim Xoxen, but this easy job, as it could be called at that time, did not last long, because they both assigned them to work in loading-unloading at the “21 December” Enterprise. Koçoja worked in that company until he retired.

Do you remember the visits you made to your father when he was in Burrel prison?

I remember that when I was little, we used to go to Burrel prison to meet my father, once I and once my mother, Uncle Koçua always accompanied us. Not infrequently, we spent the night outside in nature and when it rained and snowed, we lit a fire to warm ourselves under the arch of the bridges. We had to wait the night because it was necessary to show up at the prison early in the morning in order to register for the meeting. Only when the “Rruga e Drita” was opened, a hotel was built to be in the town of Burrel. At that time, there was no store in the prison to supply the prisoners, and there was not even the slightest possibility of providing charcoal for the cooking of personal food, which the prisoners themselves cooked.

So we had to take with us a large and heavy load, which included coal, leeks, potatoes and beans, dry meat, cabbages, and other vital things that father needed to keep alive soul in prison. It should be emphasized that we, as people with political influence, had no one to help us along the way, to carry these heavy loads. Back then, there were no taxis like today. So Koçua, after we got off the vehicle that took us to Burrel, threw the bags on his back and carried them to the designated place, in front of the prison door. Thus, these frequent trips to visit my father in prison became an important ritual of my life, even though I was a young and immature girl. This is the reason why I loved my father and uncle Koço so much.

This is the legitimate reason I hated and still hate the perpetrators of this tragedy of monstrous nationwide proportions so much. What I’m saying is so true that even today, I can never forget the sacrifices we made as a family even for the most natural and necessary thing, such as meeting the imprisoned parent. Often times, I think of removing from my mind and consciousness, these gloomy and very bitter memories, but I have noticed that it is very difficult, almost impossible, to finally remove those feelings from the layers of consciousness. Uncle, he was never separated from us throughout his life, playing the role of a caring uncle, a correct parent, aware that without his efforts and sacrifices, we would have had a very difficult time, and we would have suffered other even more serious disasters.

During the entire time of internment, my mother was constantly sick, especially recently. We will never forget the extraordinary help given to us by the doctors of Lushnja: Zografa Gjika, Lefteri Dori, doctor Çabej and doctor Deliallisi. They, with their recommendation, also introduced us to the only neurologist the city had, his name was Abaz Quka. He has shown himself to be very humane with his mother and unruly. Whenever we needed him, he came to the house, giving mom, among other things, the necessary psychotherapy. The most important thing is that he, often with the hospital’s ambulance, sent his mother for a specialized visit or for treatment at the central hospital in the capital.

In Tirana, we constantly went to the house of doctor Ndroqi, who carefully visited and treated my mother with priority. In 1978, my mother developed severe acute rheumatoid arthritis, which was treated with special care and dedication by Dr. Koço Poro. Whenever we would come to Tirana, to my uncle’s house, he would necessarily come to follow the progress of the cure. This was not a small help for us, who saw us with a bad eye, not only the specialized bodies for this purpose, (State Security), but unfortunately also many of our neighbors, or fellow sufferers.

What about the Agricultural Farm of Çerma, where you were recently interned there around 1983, what do you remember?

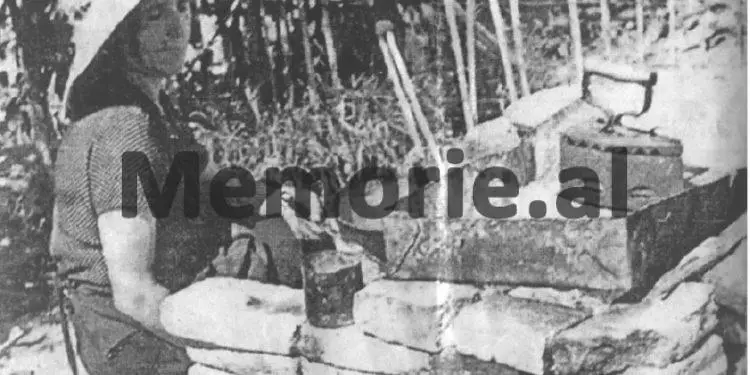

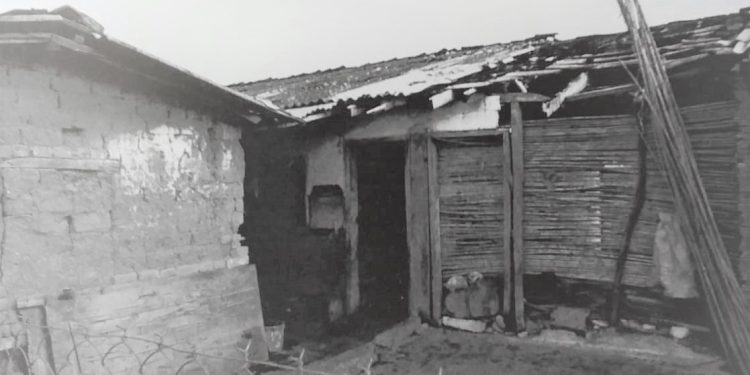

At the Çerma Agricultural Farm, we were transported in two trucks of the Department of Internal Affairs, accompanied by armed policemen, as if we were bandits. We could never have thought that, in those macabre, medieval conditions, we would stay for many more years. I remember well that, at the moment when we arrived at the building where we were supposed to live, the residents of the building, specifically the neighbor on the third floor, found it difficult to accept us to rest, even for a few moments, because my mother was sick. Later, we must have established very good relations, but the initial meeting with them was very difficult. I was assigned to work in the fourth field brigade, which was the furthest brigade and the worst paid. In this brigade, almost all its members were interned, so we were assigned to the most difficult jobs.

This brigade had another advantage that we were all the same in terms of the status of internment and treatment. In this work brigade, I got to know the children of Gani Kodra, in charge of the escort group of former Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu. Ganiu himself, currently, was imprisoned in Burrel together with the sons of Mehmet Shehu, Skenderi and Bashkimi, Mihallaq Ziçishti, former deputy minister of Internal Affairs and member of the Central Committee of the ALP, Nesti Nasen, former Minister of Works of Foreign Affairs of Albania and member of the Central Committee of the ALP, Ali Çenon, if I’m not mistaken, Mehmet Shehu’s first companion or bodyguard, etc.

I became very friendly with Gani Kodra’s daughter, Vera, and sons Genci and Artan, as well as their mother, Ikbale, who, in the conditions of exile, was a truly remarkable woman. She used to get the milk for Pandi and send it to me with Vera’s toads. Iqbalja was a very interesting, courageous, practical and very humane woman. She helped them with whatever she could, especially those internees who lived alone, without anyone and without any help. This friendship with this noble family continues to this day, especially with Vera and her family.

What do you remember of any specific event during the exile in Çerma?

One of the strangest cases is that of Jani Qehajaj from the minority, a former political convict, initially with death, then this sentence was returned to 101 years and, when the new Criminal Code was changed, it was returned to 25 years, because, there was no greater punishment than that. Finally, as a result of several amnesties in a row, Jani Qehajaj, who had been an excellent student of the Financial Technical University of Tirana and very few people know that he was a special collaborator of Albanian counter-espionage. He entered and left Hellenic territory freely. In Greece, Jani Qehajaj felt at home.

Without elaborating on the duties he performed, before he was arrested in 1950-1951, people said that; Jani was a State Security man. In fact, when he was arrested, they were not only surprised, but said that by carrying out the tasks given, he must have played a “double role”. Jan was sentenced to death. They kept him in chains, hand and foot, until the sentence given was executed, which was never carried out, but was commuted to 101 years, which meant life imprisonment. But he did not say that Jani would remain in prison for life, because the sentence from 101 years was converted to 25 years, when the new Penal Code came out.

Jani was in prison, worked in labor camps, in mines and was a perfect specialist in the organization, division and complicated calculations of works on construction sites. In the Technical Office of the mining sites, Jani felt himself in his center of gravity. He understood well and like no one else the complicated labyrinths of corruption, bureaucratic administrative and fraud of fictitious accounts, that the Ministry of Internal Affairs systematically lied to the state.

How did Jani Qehajaj’s life go after being released from prison?

All these vicissitudes of Jan, my husband, Robert Vullkani, told me. As for Jani’s vicissitudes, after leaving prison, I will tell them. After Jani Qehajajn got out of prison one fine day, around 1988, they brought him together with his parents to the farm in Cerma. Jan’s parents both died very soon and Jan was left alone and without help. He was helped only by Bali, the wife of Gani Kodra, with her daughter, Vera, who was a dentist and played the role of a volunteer nurse, giving quick help to the internees, who needed it so much. Jan was also helped brotherly by the exiled Kosovars, who were treated worse than Hitler by the regime of Enver Hoxha. Not long after his parents died, Jan died himself, although he was relatively young.

At this time, one of his brothers appeared and became alive, who had never appeared to meet him and help him neither in the interrogator nor in prison, nor during the time of exile, when Jan lived in Çerma, with parents. Do you know why this palo brother of Jan came to Çerma? To get the few lek that Jani had in the savings book! I want to ask you, dear friends and comrades of Jani Qehajaj and you dear readers: Do you know that there are also such brothers?! Don’t be surprised, there is! Our difficult life, in the internment camps and prisons of the brutal Enverist dictatorship, taught us these dirty shacks of life, which the dictatorship built.

What about a typical case, from the humor or wisdom of everyday life on the farm, can you tell us?

Human life also in Çerma, where political internees lived but also ordinary internees, for various reasons, continued its course. People, as crippled as they were, fell in love, got married, gave birth to children, got sick, died. Another episode, from our daily life at the Čerma farm, was the wisdom of the mother of Odise Collos, the son-in-law of Dhimitër Kotefa, from Sopik. This wise old woman lived in Cerma for six months, in the village for six months.

I, the old woman said, joking between us, of course, I stay with you for six months, that is, I am with Odise, six months I am in the village, that is, with the cooperative, meaning the state. When she went to the village, she left the house keys to the most sophisticated thief in the village and said: “… my wife, when you leave the keys to the farm thief, he does not have the courage to steal from you, because he will not be ashamed of the village.” It turns out that there are more skilled thieves than him. That’s how I’ve been doing it for so many years and I’ve never lost anything…”! Memorie.al

The next issue follows