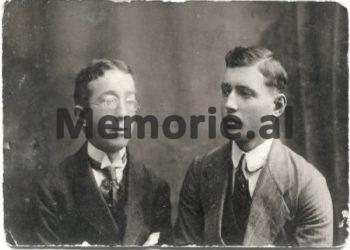

From Gani Kupi

The first part

Memorie.al / “Before the Germans left Albania, my father, Shaban Kupi, was a fugitive together with his brother, Abaz Kupi. And after Abazi fled to Italy, together with his two sons (Petrit and Rustem) and some friends, my father, Shabani, continued to be on the run for a long time. So he was always away from the family home. I remember one occasion: it was evening and I suddenly saw my father in the yard, which had come secretly. After he asked me about some family problems, he asked me to prepare some clothes and food for him to take with him. During the conversation, he headed towards a room which was off the roof of the house, separated from the courtyard, but he saw that the door was closed. There were 10 partisans, whom the Neighborhood Council had assigned to us for housing and food.

I told my father that there were 10 partisans of the 9th Assault Brigade there. Of course, the father was armed with a Greek “Maliher”, a “Nagant” and two bombs, but he did not take any further action. We gave him the clothes and the bread and after he said goodbye to his grandmother, his mother and the children who were there, he left.

It was natural that for 4-5 years that he has been a fugitive in the mountains, he may or may not have slept 4-5 nights inside the house in a year. From time to time we would send him food and clothes to a house in our neighborhood, where he would come in the evening, take them and leave, since in the evening, the ambushes set by the State Security and the police had not been dispersed.

Baba knew this experience from the time of fascism, during which he lived on the run. Before we were interned in Berat, my older brother, Sami, was taken to the Department of Internal Affairs twice in one night, asking him to inform, if he knew where my father was, and; “do you bring food, change”? Like this…!

I, Ganiu, at this time, was in high school in Tirana and I was there even when the family was interned in Berat. At this time, the chairman of the Executive Committee in Kruja was Hamit Pengili and the secretary of the Party, Saba Hasa, both from Croatia. When the family was deported, Zenepe Kupi (grandmother), Aishja (our nana), Samiu (elder brother), Fadili, the brother behind me, Kumrija (sister) and the younger brother Bashkimi were at home. After they loaded the clothes into the car, the police took away some mattresses and quilts, because according to them, there were too many. After this episode, they were sent to Berat.

The fate of the mattresses and quilts was the same as the fate of all the linens and furnishings of the house, which was quite complete for the time. In addition to these, we also had a pantry, which we called “Isuf’s room”, in which we stored sheep’s wool, the sacks of which reached up to the beams of the house, and six magrips, with olive oil, a plow, a horse saddle, etc.

In Pyllin e Bute, which was one of the properties seized from us, we had: 50 wild horses, over 50 head of wild cows, 4-5 oxen, two saddle horses, a small mule, 150 sheep, and 150 goats.

Whereas in Mamurras, we had 2 pairs of houses. In the house that was somewhat older, the first floor was used as a shop, and the second floor for housing for the workers who worked on the outskirts of the lands. There was also a wheat and corn mill. But the house, which was newer, was demolished to the ground by someone, taking the materials, to fix another house for themselves.

This was the chairman of the Cooperative at that time, who also demolished two other buildings: one was the flour mill building and the other was a one-story building, 6-7 meters long, where Kola from Elbasan (an old man) slept as well as Molla, who served both in Mamurras and in Kruja, or any other who could spend the night outside.

In Mamurras, we also had a coal warehouse, with an area of 20 X 7 meters. And others that I don’t remember now, but all seized. We also had 4-5 farmers there. In Kruja, we also had a shed that housed a cow and a small mule. And exactly that room, which father wanted to enter and where the partisans were sheltering, was the bar warehouse. Next to the warehouse, there was the gate and behind the gate, the garden bordering the street of the neighborhood.

I stayed at school in Tirana, after my family was deported. After we had 3-4 days off, I came to Krujë and stayed with my uncle in the “Meçe” neighborhood and, after four days, I went back to school in Tirana. In the “Zim Zenel” neighborhood, a checkpoint was set up by the Kruja police. They stopped me and took me to the Internal Affairs Branch. From there, those of the Branch sent me to the Durrës Branch.

In the Kruja branch, I remember seeing the late Sabri Veseli, whom we knew well since we were on the run there in a town in Tirana, with Abaz Kupi’s detachment during the war. At the Durres Branch, they asked me if we had any acquaintances in Durres and I told them yes (we had my aunt and the Belegu family), but I preferred not to go anywhere and decided to sleep in a hotel. Asking around, I found a hotel.

But I didn’t close my eyes all night, because the hotel bed had bed bugs. When the day dawned, after I had breakfast in a breakfast room, I left for the Internal Branch and after a few hours I was sent to Berat. They put me in the car with the Deliallisi (Fajë Bej Deliallisi) family from Shijak, consisting of Fajë’s mother, Fitneta’s wife, Ideali’s son, and two sisters. In the same car was another family with the last name “Mancaku” from Shijaku.

After we arrived in Berat, the family was as happy to see me as they were sorry, because they had hoped that at least I was saved from deportation. There in Berat, I saw many exiles from Kruje, such as: the family of Dar Teta, Muharrem Sallaku, Sabri Shani, Sul Merlika, Zini Lez Paja, etc.

From other districts, I well remember the family of Gjon Markagjon from Mirdite, Cen Elez from Dibra, Gafurr Spahi from Lume, Papalilo, and Llesh Marashi, whose daughter, Rexhina, I had in class. After Lleshi was killed, the family was released. Llesh Marashi’s friend was called Rozi and she was a woman of great courage. There were also many other families, from different provinces of Albania, that I don’t remember now.

In Berat, at school I entered the 3rd unique class and I was arrested without passing the exam in the Science of Nature lesson. My teacher was Bukurie Protopapa from the city of Berat (who was put in prison afterwards); in French, we were taught by an old man, Petro Koçivaci, and later, Jani Verceçka; in language, Zef Shpani from Mamurrasi in Kruja, and later Kolë Ashta from Shkodër and Majhid Daiu from Elbasan. Geography was taught by prof. Kostaq Stefa, mathematics prof. Shundi from Korçe and knowledge, prof. Shtino from Gjirokastra.

Of all the teachers, only one of them treated me harshly because I was an exile, who seemed to have communist views. Two of the professors mentioned above, imprisoned them (Kostaq and Mejiti) and found me in prison, after I was arrested in front of them. During the time I was at school, we also did voluntary work: we went to the villages to drown the shrimps and during the work, a professor from Shkodra taught us to sing an Italian song, among others, I remember the words: “Il tuoi capelli sono neri”, etc. In class, I sat in the second bank from the door and my bank mate was Fatmir Dollan, with a brother who was shot.

I found his father and grandmother in prison when I was arrested. One beautiful spring day, Sunday, I wore for the first time a pair of sandals, made for me by a shoemaker from Shkodër, who worked in Berat and was called Daut Myftari (he helped me a lot and with whom we stayed friends; Dauti’s brother Qamili also went to prison later). As usual at 3.00-4.00 in the afternoon, wearing my new sandals, I went to the Home Branch to report, as my brother and I were ordered to report twice a day, while the others, the heads of the family, reported Once a day.

When I entered the permanent office, aspirant Emërlla Kuta, from Mallakastre, took out the nagant from the case and pointed at me, ordering me: “Hands up!” And I threw my hands up laughing. The aspirant told me: “In the name of the people, you are under arrest!” But I still laughed and told him: “We are under arrest, while we are exiled!”

Then he accompanied me and took me to the roof floor. The roof was slated and the tiles were Marseilles. The roof was divided into two parts. There was also a dividing wall in the middle. As early as the first night, on 28.4.1946, that I was arrested (my brother Sami had been arrested before, when he had appeared at the Branch according to the rules), I was taken to prison.

While I was in prison, after a month, they tied my hands as they used to do with prisoners, opened the two inner iron doors and took me to the Department of Internal Affairs, to an office where they were; Selfo Bilimbashi, (vice president of the Branch), Thoma Bardha from Myzeqeja, Paskal Andoni from the district of Saranda (all three, with the rank of “captain”) and aspirant Zigur Lelo. Paskali questioned me and during the beatings, my mother cursed me. I make everything halal, not cursing.

The other three officers did not touch me, but when Paskali beat me, they told me, sometimes one and sometimes the other: “Tell me everything, don’t suffer in vain”! The accusations were that; “you know where your father is on the run”, “you wanted to run away” and “you spoke against the popular government”. In conclusion, I did not accept anything, and after two hours they took me back to prison. Sami was on the roof of the prison. We both knew very well where father lived, but in no way did we open our mouths.

When we were not put in prison, we had constantly received letters, which my father’s uncle, Met Shani, took to us. The writing was Dad’s and the signature was Matt’s. We received these types of letters even when we were in prison, from time to time. We were familiar with the writing of my father, who was still on the run.

After they tortured me, they took me back to prison. When I entered the ” dungeon” (as the isolation room was called), the prisoners began to ask me, what was on my face that was red and swollen.

I answered that I had mumps, but they had understood very well that it was not mumps, but traces of torture. And since then, they didn’t ask me anymore. And by the way, they used to ask me “what news do we have?” and “what was the Voice of America saying”!

I, thinking that I could trust the prisoners, told them what I had heard, as long as I was outside. But, after I returned from Dege, an old man named Haziz Bey Malasi said to his roommates: “Don’t ask this guy about any news from abroad and since…”! And since then, they didn’t ask me anymore. I understood this intervention, when someone in the room told me that; “There are spies here in the prison”, which I didn’t know and since Haziz Bey Malasi spoke to me, I didn’t open my mouth anymore. Before I could trust someone, I had to know them well.

So, while I was in prison, my brother Samiu was in the Internal Affairs Branch, undergoing the investigation process, where he was tortured. One night, I saw through the window of the room, how a prisoner came out of the iron door with his head and hand tied with a white bandage, and then they put him in the 6th cell. It had been my brother, Sami, as I found out later. After a while they called me, took me out of the basket, tied my hands behind my back and took me to the Branch.

For clarification: “basket” was called an iron cage, which was approximately 2 meters high, a type of room composed of iron bars all around and with a door made of iron bars (70 cm x 70 cm). To enter the prison yard, you had to crouch. There in the middle of the prison yard, there was a water well, but it was sealed with cement, and next to the well, there was a pipe, through which we filled water to drink and to occasionally wash the barrel with olives, so that his identity was coming out.

By the way, the olive trees of Berat have saved our lives in prison; we bought them through the prison window, with money that our poor families brought us, when it was the turn of the meeting once a week. And what I was talking about… well, they tied my hands and took me to the Branch. I don’t remember who accompanied me to the branch. From the first night, they put my shoulders against the wall, took off my sandals and ordered me to stand still. This torture continued for three consecutive nights.

Then they took me one floor below, where the investigator Paskal Andoni and others were, they tortured me again, but, despite the pain, I could not accept all the accusations they made against me. After two or three hours, they took me back upstairs and left me on my feet, without sleep or bread. There I understood how a person ceases to be a person. Why? Because of the lack of sleep, my eyes looked like they were filled with sand. One night, I said to Shyqyri Kavaja, the policeman: “What are these songs? School kids?” It was about two past midnight.

Shyqyrija was a very good policeman. He said to me: “It seems so to you. It’s two past midnight now, there’s no one on the street.”

In the interrogator, they put me in a room where Hamdi Sefa, from the Sefaj of Lushnje, was. He had finished the investigation and was waiting from day to day to be taken to prison. I remember that there was also an old man from Chameria, whose name I do not remember. One day, Hamdiu suggested that I sign the minutes, just to pass the queue, because I felt sorry for him as a young man; he probably had kids around my age.

Told me; “do it, because without a punishment, you won’t be saved anyway”. There, from that church, with my ears I heard him cursing in disappointment to himself: “O Albania, my mother is my mother/ because I have asked for you with arxuall (prayer)”! And I heard him beg the investigators: “Kill me, because by God, you won’t have any complaints from anyone!”

But the investigating officer answered: “You are begging to die, but who is going to leave you, without telling everything. And there is no God, did you understand or not?!” After a few days, they took the old man from Chameri and I don’t know where they took him. The guards, who worked there, as far as I remember, were four: Dan Saliu from Buzmani in Kukës, Shyqyrija from Kavaje, and a young man named Misto and another from the village of Lushnje, with the surname Xindolja. The first three were very good people, while that Djindolja wouldn’t let me move.

One day, he put the bayonet on the rifle, which I thought he was afraid of, that I might grab the rifle. And Mistoja, one night, said to me: “I don’t know where to run, that I would take you with me and we would run away.” I know well what prison is; I stayed in the Gjirokastra Prison, where drops of water dripped on my body”. Dan Salihu, was a soldier of the Division of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, with all of Jindola; the other two were policemen.

From Dan Salihu, I also learned about the event that happened to my brother, Sami, after he had jumped from the third floor window, Dan had been a guard in the Military Branch, just below the Internal Affairs Branch, but, they were somehow opposite each other. – Tetra. Dan Saliu told me: “A small noise was heard ahead, and after a few seconds a moaning ‘ow!'” Then I saw Sami, who stood up and started walking slowly…”! So, I continued to be tortured, punished to sit on my feet, without bread and without water, when one day the police took me and took me to the interrogation room.

Paskali told me: “I am reading and listening carefully to the minutes”! In the minutes, it was written that; “…he is the grandson of Abaz Kupi, and the son of Shaban Kupi, both criminals of the Republic of Albania. Born and raised with reactionary feelings, enemies of the people and People’s Power. He did agitation and propaganda against the People’s Power…he wanted to escape abroad…”, and some other words, which I don’t remember. After a few days, they took me to prison, where I met Sami.

After I finished the investigation, they gave me the mattress and the quilt, and placed me near a window. The windows were flush with the soleta, approximately 40 cm high and about 1 m long. One morning, I heard my grandmother’s voice. I scratched a little with my fingernail the newspaper that had been put on the glass, and I saw the grandmother calling the policeman: “Please, take these foods to Ghana”! He had a grinder in his hand, which took a glass of milk (I knew it was the house grinder) and an egg. The policeman told him:

“Do not worry; I will take it to him from now on”! And the grandmother ran home. I waited until close to lunch so they wouldn’t bring me anything, but they didn’t bring me food. It seems that the police kept them to themselves.

In the interrogator, we were 7-8 meters away from each other. Here I got to know Hamdi and the other prisoners, like; Estref Mufti, Ahmet Dollanin, Gani Dollanin, Muharrem Therepalin, Enver Vranin, Sadi Kuçin, Mehdi Dobrushën, Isuf Ngruçanin from the “Vakëf” neighborhood of Berat, Jup Kokoshin also from “Vakëfi”; Ahmet Xhindolin, with his brother Ismail, Ceno Velmish, Hyso Çela, Banush Saraçin, Rrap Qerretin, Enver Karrapatin, Asqeri Arifi, Vehxhi Buharana, who also translated “Gjylistani and Bostani”, Fatmir Shehu with one hand, Petrit Mufti, Myrto Malasin , Xhavit Malasin, Demo Veli with his son, Pasho Veli, Nexhip Zdravë with his son Qani, Dylaver Çarrogjati, Ferik Zhapokika, Baba Tahiri e Kuçi, Dervish Rizai and Dervish Reizi, who was young, and who seemed to be Rufai.

Likewise, Baba Bajram Plashnikun, Baba Sami, Maliq Backën, Refik and Tefik Çepelen (two brothers), Isa Godon, Lirie Luari, Qani Dinen and Qani Malaj, both from Mallakastre; Gani Limza, Qamil Kadrina (who were both killed by the police when they went to work), Karafil and Gani Zhepova, who had been officers of King Zog, Ismail Kolaverin from Mati (also a former officer of Zog), Banush Hazizin, Hysen Strani, Kamber Dobrushë, and many others…!

One day, we went to “pajtoz” (that’s what the “paradise of prisoners” was called, that is, “airing hour”). It was an exit to the courtyard inside the prison, which was no larger than one hundred and fifty square meters, surrounded by high walls, on which armed guards watched. The exit to the prison yard was one hour before daylight and one hour after daylight.

We walked in circles, but we weren’t even allowed to talk to each other. Unfortunately, Nexhip Zdrava, when we were walking in line, saw that his dish was spilled and stopped for a second to remove the lid of the pot, which was boiling in the charcoal brazier, and policeman Kasemi from Gorishti i Vlora, called: “Nexhip, come here! Why did you stop and touch the dish?” and slapped him in the face, so hard, that I believe it was heard even beyond the prison. Memorie.al

The next issue follows