By Selim Mustafa Hasanaj

The third part

Memorie.al / I will write from my memory, even though almost three decades have passed. This is a more or less biographical, personal story in which, with the greatest sincerity and respect, I will also write about other people, that fate may assign us to meet them, to know them and to share our history with them. . I was poor. The only one in the family, I was busy working. This was also the reason why for years I made chalk dodges in the Yugoslav military service, every time I received an invitation. In my heart, I wanted him to never do that service, because I didn’t want to serve the army which, for four decades, had conquered and ruled me. Several times I even thought of injuring myself, so that some handicap or disability would be caused, which would free me from joining the conqueror’s army. God often listens to our thoughts.

Continues from the previous issue

A full week passed until Captain Ljubomir Cvetkovic took all of us Albanian soldiers in his informative talks. Today, as I am writing these events, I wonder how perfidious the Serbo-Slavic military superiors have been. Even the proper regulation of the surnames was taken as a pretext to put pressure on someone, terror.

I fixed that last name myself, together with my father-in-law, after I got married and when I wanted to do my wedding, I saw that my wife’s last name is written in the Slavic language; Hoxic. Thus, Serbian-Montenegrin officials have bastardized and Slavicized our names and surnames for decades.

My father-in-law and brothers-in-law, who all had the last name Hoxha, but as was common in patriarchal families of that time, and since my lady had just finished five years of primary schooling, she stopped schooling and joined the other girls of the family. her, because they lived together with three cousins and their families, a total of 75 family members, no one can correct her surname.

The boys have fixed it, as soon as they have registered high schools, no one cares about the girls. So now when I wanted to do the kunora, I fixed it myself. My brother-in-law Enveri, when Captain Cvetkovic asked me about him, he was a primary school student.

The cruel state had some diabolical plan against my brother-in-law, who was only 14 years old and who had no fault, why did he have the name Enver and the last name Hoxha?!The superior of the secret military service of Yugoslavia knew this too. I would be in a lot of trouble later, for that job. This first meeting was just the beginning.

Since almost all of us were there in Bihaq, after a while we would be dispersed to all parts of Yugoslavia, after that day (that is, after March 7, 1981), we were no longer invited to informative talks, as if they called them torturous and extremely provocative talks, who lived with us, our Serbo-Slavic superiors.

Personally, I couldn’t wait to leave that place, and I kept hoping that after going to Zagreb, I would be able to be released from the military service there, because of the problem I had with my leg.

The day came to run away from Bihaqi. It was April 8, 1981. Surprisingly, I was the only one going to Zagreb, they split us up and made five of us. I remember that Adem Zekaj was sent to Rijeka, the others, I didn’t even manage to find out what happened to them!

The chief from Skopje was sent with me to Zagreb, but not to serve there, but to the hospital because this boy was found to be suffering from tuberculosis.

He was young, he told me that he was a poor peasant and that they lived with wood, which they carry from the mountain with a donkey and then sell it to the citizens and to any baker. He was very upset because they had told him that he would most likely be released from military service as disabled.

Tuberculosis was considered a dangerous disease and those who suffered from it were exempted from military service. That day, I traveled to Zagreb and they also gave me Shefketi. He instructed me to accompany him to the “SHALLATO” hospital and translate for him there. He was upset and sometimes, even your eyes filled with tears.

Once he was redeemed and told me; “Brother, let’s be honest, neither I nor you, I don’t like to be beaten and I don’t want to serve this army of this country, but I’m my brother, I come from a district where some merciless customs reign. If they release me from the army, I will remain single forever, because there among us, no one gives brides to boys who do not accept them in the army, or release them from there”.

I remember that right then and there, my mind went to fate, something that is determined by someone else, not the person himself. I fought with all the means to be declared invalid and to be released from military service, and only God knew if I would succeed, while this deserter did everything to complete the service, even with pain and suffering, because otherwise, he will be branded as incapable of life.

We arrived in Zagreb in the evening. We went to “Shallato” and there they accepted us, they gave us a bed to sleep that night and I spent almost our night, you read the Croatian magazine “ARENA”, the Serbian one “DUGA” and solved the crosswords in “EUREKA” and “ENIGMA “, these two puzzle magazines, which I loved very much and had as a hobby. I missed reading something from civilian life, not only military and party material, as it was imposed on me in Bihaq.

The next day, April 9, 1981, for a couple of hours, I had work with translations, you helped Shefket, and after that, I took tram no. 11, with which I went to the “BORONGAJ” barracks. I knew the city of Zagreb well and had no problems finding my way around.

Until the tram left in the direction of Dubrava and Borongaji, I remembered the case of Marka Musa, who was killed by a Serb on that tram a few years ago, and the rhapsody Augustin Ukaj sang a rhapsody to him, which was written by the well-known teacher from Berkoci i Gjakova, Mr. Prenke Bezhi.

At 15:20, I arrived at the “BORONGAJ” barracks. There I was met by the captain of the first class, Lubić Zeljko. They sent me to the room where I would spend the next time and I was happy when I saw that there were Albanian soldiers there. There I met these soldiers: Sylë Haziraj, from Orroberrdë village, Istog municipality. (I identified my father, uncles and I knew who they are). Then the soldier Rexhep Sumiqi, from Rashani i Stari-Tërgu.

Qamil Gashi from Ujzi i Hasit, a certain Myrtezi from Skopje, as well as a Serb, with the last name Otashević, who was from the village of Bellopojë near Rakosh, whom I married before. So somehow I felt good when I saw that there are good people there, whom I met and I would definitely have a good time with them.

That night I slept well, because I felt good after meeting these soldiers. In reality, they were on the verge of finishing their service, but I found out that there are over 1,200 Albanian soldiers there, and that in total there were about four thousand soldiers in that barracks.

They told me that the group of bakers has a commander, Colonel Filip Koteli, who they said is an Albanian from the Tuzi highlands. They told me that colonel was strict and dangerous. There in that barracks, but in a different gender, I knew that I also have my brother-in-law, Skënder Hoxha, and I couldn’t wait to meet him the next day.

After we were awakened by the sound of the trumpet, we went and lined up as usual, to welcome the raising of the flag. After that, we went to eat breakfast. We used to go in line and the long wait, I didn’t like it at all, I would get out of the line and go somewhere else, but I was hungry and I had nothing to do. It was a torture in itself, this waiting.

The Serbo-Slavic truculent superiors, indoctrinated with communism, put into practice what they had learned in theory during their education. They, because of a soldier who was not good in behavior, in visual appearance, who disturbed the peace, etc., etc., completely condemned the company. If someone reacted why, the squad received another punishment from the superior.

And after they pronounced the sentence and lived it in practice, they did not forget to say; “Look, you are now asking him because of this and that, you know your methods of revenge. You have enough of them in the bedrooms…”! This work of the qabe, was a dangerous “game” for the soldiers to be grouped in groups, they often played it beautifully, against someone they hated or wanted to take revenge for something.

So, with a casket in his hand, a soldier stood behind the door and when the soldier who was to be punished came in, he threw the casket on his head and at that moment, some others jumped up and punched him mercilessly, and they often used their shoes, boots and other strong things, to shoot him.

After the victim fell and lost the power to defend himself, they fled, and by the time he removed the hood from his head, none of the attackers were inside. Thus the attackers were unknown and escaped unpunished.

So the Serbian-Slavic communist superiors, the most perfidious, encouraged the soldiers to use methods against each other, which were probably only used in the times of the slave-owning system, with gladiators.

Such victims in the former People’s Army of communist Yugoslavia were usually the soldiers of the Albanian nation and why they were, are the following reasons:

Many of them did not know the Serbo-Croatian language and did not understand the commands and orders of their superiors, which is why they made various mistakes. For those mistakes, the entire company was punished and it was normal that the other soldiers, especially the Serbian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Macedonian ones, were irritated and then threw the cape at the Albanian soldier, in the first instance.

There were also those who had come to the service with dossiers prepared by the district and municipality where he was born, that is, with dossiers and reputations of hostile types, such as: “Son of a nationalist, ballistic, revisionist”, “he has around friendly irredentist”, “was associated with this and that”, etc., etc. All kinds of fictions were prepared and staged for these people, in order to punish them even with hangings on top of them.

I had heard all this before, from thousands of friends and cousins who served in the army, and I admit even now, that I did not believe them. Well, now I see them almost every night, with my eyes.

And this irritated me too much, because I saw that it is the superiors themselves, who instigate this terror against the sons of Albanian mothers, whose only fault is, because they are Albanians, otherwise they are the best and most disciplined soldiers. I was convinced that we are vulnerable and that for us the laws of the state we served did not apply and did not protect us.

Preoccupied with these thoughts, I finally got breakfast, which was a big bowl of tea, a cheese “ZDENKA” and a thin sheet of sausage.

When I reached out to take the salami, a sergeant winked at me; “BRKO TO JE SVINJSKA SALLAMA, NEMOJ DA POKVARIS VERU” (O quack, it’s pork sausage, and beware that you’re breaking the religion).

This irritates me too much and here’s the trick; “You don’t know my religion at all, so do it well, don’t provoke me.””Yes, aren’t you Turks, you Albanians”?! – told me. “No, sir,” I told him. – We are Albanians and we have nothing in common with Turks and Turkey, except that we remember five centuries of slavery”.

I spoke emphatically and I was not even afraid of this man. He was superior, but not of my platoon and I was surrounded by old Albanian soldiers, somehow I felt stronger and my courage somehow increased.

Remember that Rexhep Sumiqi came to my side and told me; “Eh, I wish you luck, you are brave from the beginning”. Sylë Haziraj whistles and tweezers; “SITNO” JOS 13 DANA” (Details for 13 days). Suddenly, as if in a chorus, the whistles started and that SITNOOOO… of the old soldiers and this scared the sergeant, he ran away, but he didn’t forget to remind me that he and I will see each other again.

After I sat down to eat breakfast, Skenderi, my brother-in-law, appeared in front of me. Oh how happy I was, I gave you a hug. He is by nature a quiet person and a bit of a loner. He was also happy and waited for me until I ate and together we went to the canteen. I bought a beer, while Skenderi got a coca-cola. As soon as we started talking, we were surrounded by young soldiers.

“I’m Zef Ndrecaj,” a red-haired boy with curly hair told me, “I’m from Krusheva e Madhe, near Klina.” “I am Idriz Musliu and I am from Gjilan”, another told me.

“I am Haqif Maliqi, also from Gjilan”, Gani Pllana from Pristina, Metë Cacaj, from Deqani, Samiri from Podujeva, Mehmet Bajramaj, from Strellci, Nazmi Shehu, from Prilep i Deqani, Avdullah Vokshi, from Peja, Shaban Dreshaj, from Prigoda and passed between them, seeing that he is also a neighbor of mine, I hugged him tightly. This was Enver Pepaj.

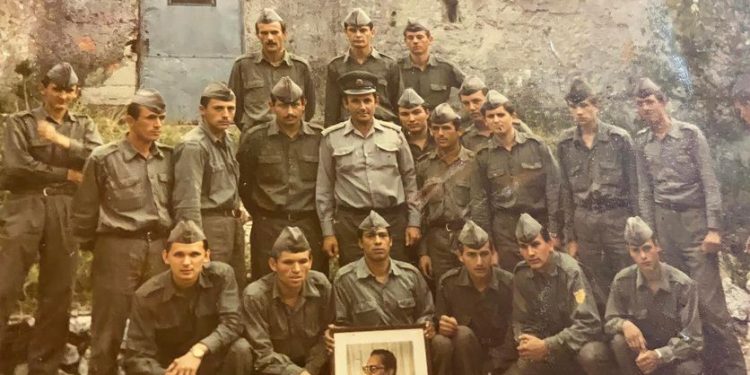

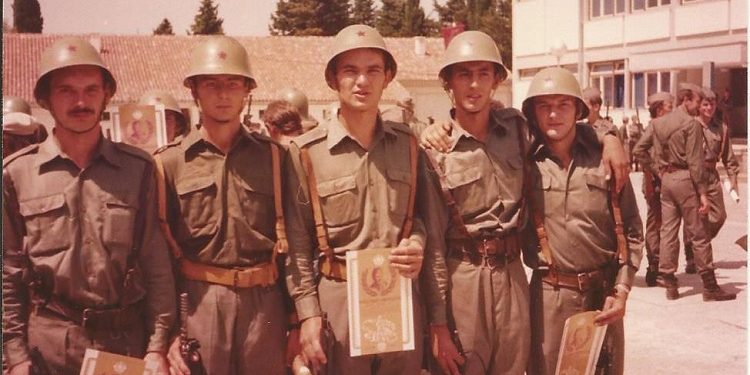

We all got together and went outside to a lawn to chat. After a while, a soldier with a camera passed by. “Do you want to take a photo of them together, how are you, – he told us, we are from the Photo-Club here in the barracks”. Take some pictures for us, which will cost us a lot later. Memorie.al

Sarpsborg-Norway: 6.11.2010