From Dom Zef Simoni

Part fourteen

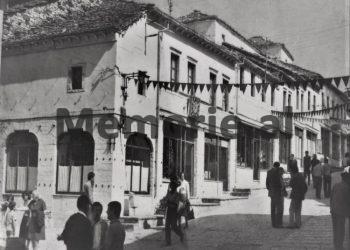

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, titled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990,” in which the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodra, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, dwells extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. Dom Zef Simoni’s full study begins with the attempts by the communist government in Tirana immediately after the end of the War to detach the Catholic Church from the Vatican, first by preventing the Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Leone G.B. Nigris, from returning to Albania after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and then with pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushti, who sharply rejected Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

Everything was done with a strict order. There was no external confusion in the camp. At five in the morning, the wake-up was carried out. One could hear the loud voice of Dhimua, a former officer, and after his release, following almost twenty years in prison, the voice of Jorgji, a Vlach shepherd, would be heard. They were imprisoned town criers. Waking up was a difficult word for us. The eyes of the prisoners would open during the night, and they carried the sadness of the day when a beautiful and bright sun rose among those dry mountains, while the prisoner took consciousness of his own condition. Every day, the prisoner could forge a formation or a ruin of his own life, through which he passed. He went to work, in the underground tunnels, and even those who did not work in the mine found themselves in the tunnels of cruel wars, encountering the most horrific positions on our Earth and continent. And you ask yourself:

What am I doing here, where am I, why am I here?! To be here for just one day and night, twenty-four hours, makes you feel worthless. But to be here for days, weeks, months, years, for your whole life – many even die here. Everything had to be done quickly after waking up to fulfill personal needs. An anti-human torture in those WC’s without doors, thirteen in total, and quickly washing in those few faucets with little water for all the prisoners. There, we also washed clothes, having few tubs. Everything was little, cramped, and rushed. A coming and going, a movement of people, many of whom even rushed like madmen, because the time around 7:30 was approaching, when the crier would announce the next roll call (apeli).

For this, everyone would gather on the terrace, climbing a few steps. The terrace was large, where a walk could even be taken, which was sometimes allowed, but mostly not, because from there one could see a little more, and a corner of the road was visible. The roll call was held regularly twice a day, and it began to be held three times, after the death of the second dictator, Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu. And until the counting time came, we would often stand for an hour or more, in the rain, in the cold, in frost and ice, and even in the peak heat of summer.

This was a heavy hour of our oppression. We passed two by two, descending the stairs, taking off our caps, and exposing our bald heads, in the presence of the duty officer and the police, to pay our respects, to prostrate ourselves as if to false gods. They wanted us to have no personality, but it was here that the poison of our curse also gathered, which would inevitably fall upon the people of violence, upon the oppressors of man. Here lay the false victory of communism on one side, but here would also be ours, because in those significant and concentrated hours, daily and most prominently oppressive due to them, God’s punishment would fall upon those who violate human dignity.

Human dignity is the property of God. It is very difficult to be beaten, to be tortured with brutal, animalistic blows, to be killed, but what surpasses all evils is to be humiliated, because the one who humiliates seeks to remove dignity. Communism did not only do evil by shooting and imprisoning people, because such things have happened during unknown times in history, nor because it corrupted human character (which corruption is a consequence of evils), but mainly because communism corrupted character by systematically and momentarily violating dignity, and people themselves reached the point of lacking dignity. Why were the Nazis and Fascists defeated during the Second World War? This happened to them because they violated the dignity of their enemies. This will happen to every form of communism too. This was our certainty, and for a long time, also our morale.

There was such an organization that if you did not have a strong will, you could collapse, you would keep falling. For a part of the time, about fifteen hundred people could walk around in those two small courtyards, where I had to be careful not to let any word or conversation slip, because spies would follow you to listen. The word prison (burg) is different from interrogation (hetuesi). In interrogation, you have a strong fight, struggle, many nightmares. You rarely come out, maybe never. Whereas in prison, you have a life with a kind of bad stability. You have work, you have air. But you are stuck in something long, with days, with years, and indeterminate, because you might be punished again. If it were possible for me to stay with every person there, and if I entered the essence of those beings called prisoners, I would discover the world of their pains and see that everything is closed within them.

The Sister’s Visits to Spaç and Ballsh

In prison, you are plunged into darkness. You only have the reality of pressure. You were separated from your family, from relatives, from friends. You waited for the family members with such love. They stayed with you for about ten minutes. My sister came to visit my brother and me, so self-sacrificing for us. It is enough to recall the difficulties she had traveling to Ballsh, where Gjergji was, and to Spaç, with difficult roads to come to me, where the journey would torment her with stomach discomfort and would turn her face the color of a corpse during every trip. And all the weight of the food that she had to carry, walking on a stretch of road, she had taken from un-fed mouths. In the meeting, conversations were short, fast, and clear, and the meeting ended with final goodbyes and the tears of mothers, sisters, wives, and children. Families, to help us, also sent us packages by mail.

The Unemployed in Spaç

Those who worked three shifts in the mine suffered and were exhausted. The unemployed, who numbered about five hundred, also did small, internal jobs. There was a kitchen that they called “private.” To prepare the fire, the command gave coal dust to make briquettes (balls). All unemployed prisoners were taken outside into a yard (patalok), sitting near the command office, in the cold, frost, and wind, to make briquettes by hand. A job that lasted about two hours, almost every day, with the shepherd foreman of the unemployed watching over us. There was no need to have a better policeman. Those who worked had a bread ration of 900 gr. a day, and food for breakfast and lunch. Dinner consisted of tea with a piece of marmalade or cheese. Many times, there were those who did not eat the rice or pasta with meat, because those who extracted pyrite, in particular, lost their appetite and gave their portions to their friends in unemployment, where there was much hunger.

In unemployment, there were 600 gr. of bread per day, but even this was not given accurately. The food quota was valued at eight old lek per day. In a week, only sunflower oil might be served, two tablespoons. It was a ration. Eat the food or don’t eat it. Every winter morning, you would be served some kind of dried leeks, brought in sacks by cars, which were inedible, unsavory, and we poured them into the leftover bins for the command’s swine. “Oh, that rice soup for lunch is unbearable.” Faces would grimace. We would look for some leek or garlic that entered the camp through the command. A bowl of thin bean soup, and that only every three days, turned the day into a feast. Every evening for dinner, you would get a slice of bread and a cup of tea, almost without sugar. Amidst the heat, rain, snow, and ice, down to a temperature of minus 10-15°C, for how many years, we would be lined up, three hours or more a day, at the three meal times, to receive that food which had been prepared in such a way as to destroy any desire we had to live. Food suitable only for saints and animals.

When it rained, we were not allowed to take plastic sheeting to protect ourselves. Thus, everyone got wet, and coats and heads became drenched. We shivered especially when the rain fell in the cold. A heartless guard saw a prisoner who had placed plastic over his head. He pulled him out of the line and placed him in a position where the raindrops fell onto his neck to run down his body. Everywhere, I felt bad. Even if I had some comfort, spiritually I would not like it, because it felt as if I was thinking about staying there, for a life that becomes yours, thus prolonging the time of captivity. The disposition had to be such that we did not live with reality. It is a way to escape collapsing, to keep up your morale, and to always think, never for a moment to be detached from the future, from that which you do not have presented.

There is still life. And even if there is no more life, or if I don’t live anymore, the value is that you have not collapsed. “Frangar, non flectar”. (“I will be broken, but I will not bend”). What do I need reality for then? Forget it! Am I freezing? Move, to get warm! I am hungry! I will eat. I am tired, standing even during the roll call, more than three or four hours a day, in the rain, in the sun. I will rest and live. This is Stoicism. But there is even more for me. There is something else for the one who gives a high perspective to life. That which sanctified suffering always comes before me. Sacrifice with reward. I do not seek suffering much, but I accept it when I am in it. I have a high purpose. Christ suffers in me. And then it seems to me that I suffer less. It melts into merit. And so I work for the future.

Now we can also appreciate the essay topic that Father Gjoni gave us in the sixth grade of the lyceum: “Geniuses are formed in solitude, characters in noise.” There is little, almost no solitude. There is a lot of noise. Characters are formed here. At any moment, someone can provoke you. There are very good, polite, educated, kind-hearted people, with ideas and ideals, but there are also those who are backward in human kindness. The narrowness that is characteristic of the time and the regime gave rise to quarrels, as well as discoveries that happened among those intriguing people, spies, and the vices that permeated the camp, giving that natural pit of the prison fear and anxiety.

In prison, it was impossible for your nature not to manifest itself with all its power, in the depth of your actions. You were completely exposed. Life here had no mask. “Why, O man, O prisoner, do you go ahead of your comrade in line, when you are lined up to receive bread, without his permission, without any reason?” And this is not done by some sick person, someone who has no help, but by those who seek to profit in everything. So why then did you fall into prison? I fulfilled the idea that justice must be the first characteristic of man. If a man is not just with you, he is your beast. Are perhaps the conditions, the circumstances, everything over man? No. They influence. But they are not. The personality of man is the same in every case. I often decided for myself that I would take the bread among the last in line, without looking if anyone passed me. I kept my peace.

Only once did I ask a prisoner who, for three consecutive days, came ahead of me in line, passing in front of me. He entered and did not greet me. He did not speak a word to me. A curiosity arose in me, and having an inner anger, I asked him on the third day, with a certain tone: “Why, young man, do you go ahead of me, when I am much older than you in age, and sick? I judge these actions badly!” I told him. “I come,” he said, “ahead of you, because you don’t say anything to me, because you priests are good people. You endure. You have many reasons. – He told me, and asking for forgiveness, he continued: – I am young, and I don’t know what I am doing from the suffering. I am an only son, and my parents are in difficulty, and sick.” I also asked him for forgiveness:

“Stay ahead of me whenever you want.” But he did not come again, but he would give me a greeting in the camp. This fact was almost similar to that event when I protested in church about not giving communion to that friend of mine. A secular vein ran through me. There were many young people who were preoccupied with knowledge, especially foreign languages. During the years of prison, if anyone was discovered to be dealing with them, their notebooks and notes would be taken, and they would be isolated for thirty days. Thus, some were sometimes punished for thirty Italian words. For one word, one day in prison. For thirty, arithmetic multiplication. He stayed freezing because it was winter. He came out at the beginning of the month. His friends stayed close with food to help him recover, that face that had turned like a corpse.

The Death Cells

To enter the cell meant, especially in winter, to enter a torture chamber, about two meters long, where wind and ice entered through the holes, and one can only imagine the heavy physical consequences in these rooms called “the death cells…!” The reasons for entering were varied, and for some people whom the command considered stubborn and dangerous for their views, they awaited the smallest reason to put them in the cell. With these people, they would then organize beatings with squads of police, reaching up to 13 people.

If the guard found the smallest reason for violating the regulation: that the bed was not made properly, or eating any item, no matter how small, in the sleeping room, that’s where your place was. The cells were placed above the stream, and the cold wind blew in winter. This was the coldest point in Albania. The stream below was completely ice, and the merciless wind entered through the cracks of the cells like a cruel killer. No food other than the commands was allowed inside. The condemned person would stand all day, dressed in thin clothing, because they would take away any jacket you had. In the evening, two ragged blankets would be brought in.

Every night in the strong torture of winter, frozen with snow on the ground and ice in the heart. Camp and terror. Re-education Camp 303 Spaç, that’s what they named it. Frequent meetings were held, presided over by the command with the commander, or more often the political commissar. Those were bitter meetings, usually held on Sunday mornings. Communist poison was spewed out there, with military strictness, and they were warning signs of new arrests in the camp. There were cases where the rights of the prisoners were discussed, but more often their duties. They talked about internal organization, cleanliness, the food that never changed at all. The food was checked every day by the duty officer and the camp doctor. There were two doctors: the military doctor of the command and the imprisoned camp doctor.

The imprisoned doctor, in the infirmary, conducted visits, gave medication, and limited rest permits, not to go to work for those in the mine, and for the unemployed to rest in bed when they had a fever. The command ordered in every meeting that we should be quiet and not speak against the regime: “because we will cut off your tongue. Your snake tongue. Because of this tongue, you have ended up here. This is the ideal power.” Said the sub-commissar, Nikolla, from Puka. “Heh, heh,” a group of prisoners laughed towards the end of the hall. Not knowing the cause of the noise, the sub-commissar took heart and flared up in the face, taking on a strong, bad color. “Don’t throw venom against the power, re-educate yourselves. For this, we have also introduced the reading of the press.”

Every day, except Sunday, which was a rest day, the golden reading of the works of Comrade Enver was done, three hours a day, and in the last years, two hours, until about 10:30 in the morning. Then we would be confined to bed, so as not to make noise, we the unemployed, for those who slept to go to work in the second shift. A cemetery silence would reign, while the world at this hour is in the movement of the day and life. And while we were lying down, we were constantly checked by the police, who slowly walked through the rooms, casting their eyes on each one of us. For twelve years, I heard the reading.

The lecturer was a prisoner. We would all stand attentive. The strict foreman of the unemployed, Jorgji, was present. And when the guard entered the reading room, everyone adjusted their positions. A guard in the Përparimi section, near Saranda, where I was in the last year of my imprisonment, saw an elderly prisoner who had lowered his head onto the table. The guard, with the greatest calmness, requested a bucket of water to throw in his face, and letting out a tearing scream, he said: “Is this how you listen to the great works of Comrade Enver?!” and took him outside to take him to the command. To go to the command meant to enter torture.

It was winter, very cold. There was frost. The surrounding mountains were white with snow. It was a day with little sun, a sickly sun, 7°C. A check would be conducted in the camp, as it was done once a month. The check lasted almost five hours. They told the lecturer to read. What? The works of Comrade Enver. We felt heated. The works heated us up. Hatred, the heat of anger. Camp and terror. In Spaç, they added barbed wire, fences. There were four. Another one was added. There were five. The military guards who were day and night in control aroused our curiosity. They wore helmets. Sometimes they took them off; sometimes they put them on even during the day. We made political interpretations inside the prison. Every day we lived in fear, we had great psychological pressure.

Convictions were formed that it was difficult to get out of there anymore: from the extermination camp. A prisoner who had been in the Mauthausen camp said that Spaç surpassed it in terms of torment and terror. Words would come in: “There will be arrests these days.” Some of their agents would spread the word. There are arrests. Arrests after arrests, in prison. Without warning, without recalling, the roll call. “Apeli!” the dreadful voice called. 11:00 AM. Stop the reading. It is the roll call. Everyone stands without a sound, a deathly silence. Everyone lined up. The sky darkened for us, hearts grew dark. Everyone thought to themselves; is it me? Are there many of us? Again, mothers, children who will suffer. Again with bags to take their loved ones back with tears in their eyes, with exhausted legs. What are these events like?!

The political commissar, the commander, the operative officer, officers, and many guards entered the camp. They were arrested as enemies of the people. The guards moved through the prisoners. They put handcuffs on their hands. The arrested men held their heads high, a sign of defiance. The entire camp fell silent that day. A day of mourning. They acted this way every time. Even forty people at once. But this arrest, they carried it out without a roll call (apeli), taking them from their rooms. Again, they spread rumors that others would be arrested. Twenty-seven others were arrested simultaneously. This included the group of Fadil Kokomani and Vangjel Lezho, on February 23, 1979.

Both held strong communist views. These two had sent a letter from the prison to the Central Committee, demanding a change in Enver Hoxha’s line and his removal. They wanted to reestablish relations with the Soviet Union. They had both completed their studies there. Communism does not take hold. It possesses dictatorship and totalitarianism. For Fadil, Vangjel, and their comrades, everything had to breathe through the narrow opening of Moscow. Communism takes power by violence, and it maintains it by violence and blood. Violence and blood are the binomial of Communism. They were convinced that they were right.

Yet, the Soviet Union was a perfect example of terror, and for sixteen years, it extracted the eyes and water (drained the energy and resources) of Albania. What was the need for ties with this country and these ideas and principles?! If you are a communist, your head will be taken even by your own kind, even if you offer just a slight criticism. Fadil was Stoic, a journalist, and a literary man. Vangjel was a journalist, a literary man, and a Christian believer. They were people of courage and honest in character. Many individuals who belonged to the current of revisionism had also fallen, sons of many party and state cadres, such as Beqir Balluku, Teme Sejko, Fatos Lubonja, Spartak Ngjela, with democratic tendencies, and many others. All of them held socialist views, but were honest in character, and you could stay with them without any fear, you could speak freely, because they were truly loyal. Memorie.al