From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part twenty-three

Memorie.al / I were born on 23. 12. 1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the vile investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the brutal prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Department of Internal Affairs in Shkodër, split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, after breaking several ribs, half of my molar teeth and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the wretch Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After they cut my sentence in half because I was still a minor, a sixteen-year-old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the Reps political camp, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad; Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we aspire to. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Rilindja” government sent order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for; the dismissal from duty of a police employee. So Divine Providence intertwined with the neo-communist Rilindja Providence, and, precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced, no more, no less, by the former operative of the Burrel Prison Sigurimi. What could be more meaningful than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

Continued from the previous issue

R E P S I

Forced labor camp

Memoir

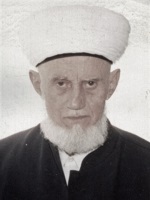

I thanked the hoxha Sabri Koçi with all my heart for that lesson of truth, which would soon be followed by other more complex lectures on Islamic philosophy. Thanks to him, I would encounter the pearls of Arab literature, I would become acquainted with the culture of almost half the world, but this might belong to a separate topic. From that time on, we spoke often and more often. That kind-hearted man induced a much-needed calm in that environment. I quickly befriended the Hafiz; we would also be together in Spaç, until the day of his release. The friendship would last until this great-souled man, physically exhausted from over two decades of suffering and hardship in the prisons of the dictatorship, spread the holy light of Islamic knowledge across Albania and passed away from this world.

One day, the handle of the hammer remained in Maqo’s hand when he was hitting a concrete block. It slipped to the side and the handle broke. Since we definitely needed it, the master sent me to the carpenter, ten steps away from our door: “Go, Çim, to the priest, get a new handle! Tell him Gaqka sent me, and give him my greetings.” It was the first time I set foot there. We were neighbors, but each person kept to their own door, neither the work nor the man who ran the carpentry shop attracted me. For as long as I had been there, I hadn’t had the chance to even exchange a “good morning,” let alone speak at length.

Without knowing him at all, this person somehow sparked a feeling of antipathy in me that I couldn’t explain. Whenever our gazes crossed, his eyes shot out some scorching sparks, which increased my dose of antipathy. He belonged to the grumpy kind. Ultimately, he didn’t seem like an approachable type and didn’t inspire a desire in me to have him in my close circle of friends. The dark-skinned, small-bodied and thin carpenter would pass by our door stooped and solemn, serious and silent, never a smile on his face. He walked with his head down, his hands clasped over his belly like those pious old women and muttered under his breath, as if praying.

When Gaqka told me: “Go to the priest,” the clasped hands and the incessant whispers that never left his lips immediately appeared before me, so I thought that they must have given him the nickname “priest” for this reason. But I never imagined that he could be a real priest. With the hammer in my hand, I entered the door. I found the carpenter folded over the table in front of him. He was planning something. I waited for a few moments at the threshold, hoping he would turn his head, but he continued his work. It seemed my presence didn’t bother him at all, in fact, not even the door that grated my ears as it moved on its hinges, nor the gust of wind that cut like a razor, drew his attention. He continued the back-and-forth movements of the plane, without losing his composure.

Waiting bored me, so I pushed a piece of wood with my foot and it hit the ground with a bang. He raised his head, turned his dark face, with all the harshness that typified him. Two deep, scrutinizing eyes, with a hypnotic light, stood out on his dark complexion. Those eyes seemed to be asking: “Why are you bothering me?” “Mr. Zef, Gaqka sent me to get a handle for this hammer!” I hurried to speak, hoping to soften those captivating eyes. As a form of apology for the inconvenience I was causing him, I heavily emphasized the master’s name.

“Leave it there, on the bench!” he ordered and continued the back-and-forth with the plane. I was left standing there, undecided whether to stay or to run away. But the master was waiting for the hammer. On the other hand, that scowling face and harsh tone of speech didn’t warm me up. “After all, I’ll try one more time,” I encouraged myself. “I’m not going to make him a friend!” and I replied: “Mr. Priest, I came here because I was sent, not because I missed seeing you.” At least, with these words, I thought I had let off some steam and challenged those cold, penetrating eyes.

He put the plane aside and turned to me: “What did you say? I don’t hear very well?” “I said, I came because master Gaqka sent me, who at the same time sends you his greetings, and because we need the hammer for work!” I softened the tone a bit. “I’m sorry I called you a priest, but I didn’t mean to offend you, that are what they told me!” I defended myself. “No, man, I’m not offended at all! And why would I be offended, I am a priest!” “What?!” “Yes, truly! I would be offended if you called me something else!” and he fixed his scrutinizing eyes on me more intently. “Now I have some other work in my hands, I wanted to finish this! Since Gaqka sent you, I’ll do it right now.”

He took the hammer and with a skill that did not match his clumsy appearance, with a swift blow, he removed the wooden piece that had remained stuck in the metal socket. He looked for something behind some plywood sheets in the far corner, where he seemed to find what he needed. “This is beech; it’s not strong enough to break concrete. If you have a little patience, I’ll make you an ash handle, but it’ll take about ten minutes to finish.” He said to me. “No problem, I’ll wait, as long as it’s a good one!” I replied. He returned again to where he had taken the first piece, but this time he came with a truncheon, with bleached bark.

“This is the perfect fit for this tool!” He took the hatchet from a shelf and with accurate and swift blows; he gave it the proper shape. I watched this harsh man with admiration; how masterfully he used the hatchet! “What is it with these religious people, all finished craftsmen!” this dilemma was bothering me. “Strange people, quiet, tireless, talented, hidden in modesty! First a hoxha master in plumbing, now a priest, also a master in carpentry!”

These examples forced me to revise my opinion up to that point. The old myths were collapsing one by one; the myth of the lazy and parasitic religious person, which they had long tried to serve to the new generation in school curricula, fell; the myth of the “Turk-like” men in Haxhi Qamili’s baggy trousers, which satirical engravings in “Hosteni” magazines, etc., presented, also fell. I remembered the simple words of the clever old Esheref; “Here they are all professors, little boy!” And indeed they were! Lost in these contemplations, I didn’t even notice the priest when he had put the handle in the metal socket and was extending the hammer to me:

“Now it’s ready, but before you start working, scrape it with glass and dip it in water!” He took the plane he had left on the table again. Before I turned my back, I thought to thank him for the favor he did me, but since I couldn’t find the right words, I remained frozen at the door threshold: “Mr. Zef… no, Mr. priest, I wanted to tell you, thank you…”! “No need, man, just Father! You understood, Father!” “Yes, Mr. Father, thank…”! “No, no, very briefly, Father!” he emphasized and fixed his fiery eyes on me.

For a moment, some muscles moved on his stony face, something like a hidden smile behind the veil of his harshness. Confused, I left with that half-stammered thanks. I spent the whole afternoon going back and forth about the meeting with Father Zef; I couldn’t figure out where to classify this person; among the positives?! The way he behaved didn’t convince me: gloomy, cold, wild; neither hospitable nor benevolent; but a man who gets things done. Among the negatives? Again, I felt in doubt; he finished the job, very quickly and accurately, without even waiting to be thanked, except for his unceremonious, slightly harsh and brutal approval. “Come on, try to understand these types, I beg you!”

When I told the elders my impressions of the meeting with Zef, the way he received me and the words we exchanged, old Eshref burst out laughing: “Bravo, kid, didn’t I tell you that everyone here is a professor! Now fate is bringing you to meet them, one by one! By the Prophet, today you met the chief professor, Father Zef! He is a great man, learned and serious! But, he is a man of few words; he doesn’t trust anyone without knowing them well! And he doesn’t know you!” When I told him that I didn’t like his sullen and grumpy face, then the way he dismissed me, without waiting for me to thank him, he replied:

“Don’t look at the suit, but the deed, kid! And what were you expecting, did you want to see some clown, grinning! He is an old man; he is still shocked from the interrogation. That priest has suffered a lot! This is his second time in prison and he has escaped the death sentence! He is terrified of the spies in the cells, only God knows what he has suffered from this race of people! When he gets to know you closely, he will love you dearly, and you will change your opinion!”

While Vaska spoke more clearly: “From what I know about Catholic priests, and naturally, I have years with them, I’m not speaking simply as a colleague, but they are much higher than us other clerics. They have completed full schools, but they have a lot of problems with the war and with physical elimination. The communist system eliminated or imprisoned almost all of them. Over time, you will learn everything. As for Father Zef, we will pay him a visit together.” With that, the conversation ended. Three or four days later, one Sunday around noon, the priest, old Esheref and I went down to the lower barrack, where Sulua and old Dauti were waiting for us.

The elders seemed to have made an agreement among them and had arranged this visit, which would open up new paths for me. One after another, we entered the dormitory door, turned left and at the end near the poplar wall, again to the left, we found ourselves in front of Father Zef’s cot. The priest, leaning on a pillow and with an old blanket thrown over his shoulders, was reading near the weak light of the window. “Oh Father Zef, are you expecting guests?” old Dauti addressed him, as the oldest one.

“Welcome, O Daut from Labëria, the house belongs to guests and to God, but here we have neither a house nor a household!” the priest replied with a smile. This sincere smile was the first surprise for me, his face changed right there on the spot. Now, I had before me a person who was diametrically opposed to that grumpy carpenter of a few days ago. “Oh Zef Pllumi, we have come to see you and have a little chat!” the witty old Esheref added. “May God bless you for bringing you!” and on his knees, he gathered himself on the narrow bed. In the cot nearby, a giant man with a turban of small flowers wrapped around his big head, where twisted mustaches stood out from ear to ear, moved in his place.

“Move a little, Çun!” the priest addressed him. “Good friends have graced us with their presence, man!” “By God, may the hour bless you, oh friends of my friend, and mine too!” the mustachioed man invited us and got off the bed, to make room for the elders and for me as well. “How are you, men?” Zef addressed us and extended his hand one by one. “You made me happy! Settle down in this little property that the government has granted us!” They sat down as they could. I was at the bottom, with my feet hanging out in the corridor.

The greetings and routine questions about each other’s health and the latest news from their families were over, they also talked a little about the wild weather of Mirdita, and then the conversations seemed to dry up. Meanwhile, old Esheref, as the most practical one, brought up the priest’s passion, wood carving: “Father Zef, how are your worries going, have you managed to doing anything good?” “As for worries, everyone has enough and more than enough of their own, and I don’t intend to burden them with mine. As for the work, how can they let you do anything here, Sheref! Man, they are not satisfied! They have completely drowned us, now they want to take our soul too!”

“You’re right! As for the rest, that’s how it is, but they don’t have our soul in their hands, but God with His Grace!” old Esheref confirmed. “A few days ago, Commissioner Sela, that guy from Korça, ordered me to make him a nightstand out of Chinese red wood, with packing boxes and a chess board, with some pieces of broom. He wants to have it as a memory from Reps, because he’s going to be transferred. It’s been a week and I haven’t finished it yet!” “You don’t like us at all, Zef, come on out, let’s have a coffee!” old Dauti intervened.

“We are tired and exhausted, my friend! All day at work, when I come back here, my strength is gone; I take a book to read, just to calm down. Besides, you know, I am a priest, I have some other obligations.” “I understand, but we also have social duties, because we’re not going to hold up the world by ourselves, my dear!” “Time, Daut, time, we have it quite limited! But, who is this young man?” He cast his eyes on me. The incident from a few days ago came to my mind, and I felt ashamed. “A friend of ours, a young one!” Sulua introduced me. “Yes, truly, now I remember, he came once to get a handle for a hammer, and I couldn’t exchange two words,” he was silent for a moment, then as if to excuse himself, he added: “See, how busy I was!”

“Oh Zef, here where they have put us, they have left us enough time to finish all the orders.” “By God, they have sentenced us for so long, to do the work of this world and the next!” old Sheref burst into a sarcastic laugh. “But, we need to ration a little, and keep the old company and miss each other!” he added with an unwavering smile; then a little diplomatically: “But, we need to get to know the newcomers, because we have a duty to guide them, if they are good! That’s why we brought our boy here, to introduce him to you.”

“The day he came to the carpentry shop, I knew nothing about him, and I didn’t get to know him!” the priest put his hand on his heart, as if asking for forgiveness. “But who is this man, because I don’t know him, and I don’t know where he is from or where he is going?” he thought for a moment and added: “Now that I see him with you, I believe he must be from good stock!” “As for his family, I guarantee it,” Sulua intervened. “I know him well, root and branch. This one is a minor, but the pear falls near the pear tree, as we say in our parts. We have a duty to guide him, and then let him choose his own path. But, since I only have four months left, if I manage to get out alive, I will do what his father would have done for my son if he were in my position. So, I want to feel at ease, before my friend, and also before my conscience, I want to leave him among friends and in safe hands!” he concluded.

At that moment, I felt as if I were a commodity being exchanged in a livestock market, where some unscrupulous horse traders praise the qualities and heritage of the animal they have put on the market. These quips reminded me of the deceptive matchmakers who praise the positive aspects of the groom and his family to the bride’s people, to convince them to get married.

I was contemplating these things at the time, but the future would cast them into oblivion, because the fruits of the experience of these clever men would serve as a lesson for me, the results of which I would enjoy later. When it was time for the clashes with the crushing rocks of pressures and backroom intrigues concocted by the State Security and its pseudo-historian collaborators, I understood how important the support of the group that surrounded you was; more or less the effect of the rubber life-saver, which protects fragile boats from being crushed against the walls of the pier.

Securing such a belt was more than a necessity behind the barbed wire. The divisions with clans and groups of the state organism had also been transplanted into those environments, even at the highest level. Over the years, some immune organisms had been created that determined the subsequent progress for each new prisoner. In prisons, there was a kind of hierarchy, which had its origins with the first prisoners of forty-five and then, through them, was inherited from generation to generation by the younger ones.

The generation of early prisoners who benefited from criminal policy, because the long sentences that started with one hundred and one years, as a result of the spirit of the laws that had been exceeded in time, with the approval of the new constitution and legislation were abrogated and the maximum sentence was reduced to twenty-five years. Now they had to serve sentences of no more than twenty-five years, except for one “very small” caveat, twenty-five years, was converted without any equivocation, into twenty-five years of real deprivation of liberty and not a sentence “in folio”, where it was enough to escape execution and then, God willing; pardon after pardon, you serve five years and you are out! This did not fit with the criminal policy of Socialist Albania.

Twenty-five, means twenty-five years in prison, period! Consequently, “life imprisonment”! This was also due to the age and the cruel treatment! Thus, the prisoners of the first generation coexisted for a long time with the second generation, and when they were released after twenty-something years, they passed the baton to this generation, and so on. The “aristocracy” of the prisons respected the hierarchical continuity for an additional reason, many former prisoners were either re-sentenced there in prison, or even if they were released for a while, they were re-sentenced again to internment and then returned to the bosom of their social group, where they regained the positions from which they had been separated some time ago.

I will discuss this topic below, perhaps in a separate chapter. During the visit we paid to Father Zef, I learned a truly original fact; the ability to adapt that consisted of accommodating representatives of the four religious faiths in the same dormitory. This way of organizing, undoubtedly on purpose, left a rare impression on me. The cost of those who, after twenty-two years, would re-establish the spiritual constitution of the Albanian nation, were arranged at a distance of seventy centimeters, one from the other. On the left side, they were lined up one after the other; Father Zef Pllumi, the one who would lead the Albanian Catholics, on the difficult path of spiritual revival, Çun Çamluk Mëhilli, the great-mustached devout Catholic from Iballa e Pukës.

After him, Don Ernest Troshani, also a distinguished priest, across from them in the space of an outstretched arm, were in order, Hafëz Sabri Koçi, who would become the legendary leader of the Albanian Muslims, hoxha Faik Hoxha, who also after the nineties, would lead the chief muftis of Shkodër, and continued with Shefqet Alla, from the villages of Librazhd, a very charming religious man, further on Sulejman Begovija, Rruzhdi Boriçi, Hodo Sokoli, etc.

On the second floor, on both sides, were lined up: on the right, Father Aleksi from the villages of Lunxheria, with Irakli Sirmo, from Dropull, and Stavri Pilafi, brilliant believers, and further on, Kosta Mitre with a bunch of rascals of the Macedonian minority, from the Prespa basin. Across from them, a group of Bektashis, led by their spiritual leader, Baba Bajram Mahmutaj, followed by Meleq Hasa, Hebib Bodurri, Rustem Gojka, etc., believers from the region of Skrapar, about whom I will speak as the occasion arises.

Maybe today it seems unbelievable, but the truth of this fact can be testified by some survivors of that time, who are still alive. Three months later, after reorganization by brigades, At Vaska and I would also be residents in this barrack. In fact, I would have the chance to be only two beds away from Father Zef, between us would be the heroic man from Iballa, Çun Mhill with the great mustache, and the priest, Don Ernest Troshani. I want to emphasize, however, that after this meeting, especially after the month of probation in the cell with Don Mark Hasi, I would form a close, sincere and long friendship with Father Zef, until his departure from this false world.

In that individual, the natural intelligence of the noble and honest highlander, but a little harsh, as a result of the conditions in which he grew up, was harmoniously intertwined with the culture and education he received in the Franciscan colleges. He was proud of his highlander ancestors, to the same extent as he was of his teachers, the great Franciscans, who had passed on to him and his generation, the most advanced world culture and the most ardent patriotism for the homeland.

His eyes sparkled whenever he mentioned these distinguished men who, according to Father Zef’s words: “Have been, are and will be, THE PRIDE OF THE NATION! No matter how much they are defiled and left without graves, their work will live on for a long time! I guarantee you, the day is not far when they will be hailed, elevated as martyrs, who were sacrificed for Faith and Homeland! Even if gold is found in the mud, it keeps its value unchangeable! Only stones are thrown at nut trees, poplars only have fluff!”

When the conversation turned to past facts and events, he told me about works and documents with rare historical value, which he had in his hands in his youth, in the archive of the Franciscan Convent. He expressed doubt that these unique documents had been stolen and disappeared without a trace, by the Yugoslav U.D.B., in cooperation with the State Security and its pseudo-historian lackeys.

He judged that the archives, which are the history of a nation, should be left as a legacy to future generations, as a point of reference, to sketch the future. Therefore, in every conversation with young people, whom he thought were worth opening these topics to, he would not miss the opportunity to mention them. But, nevertheless, he was very cautious about provocations and provocateurs. Memorie.al