By Ahmet Bushati

Part twelve

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

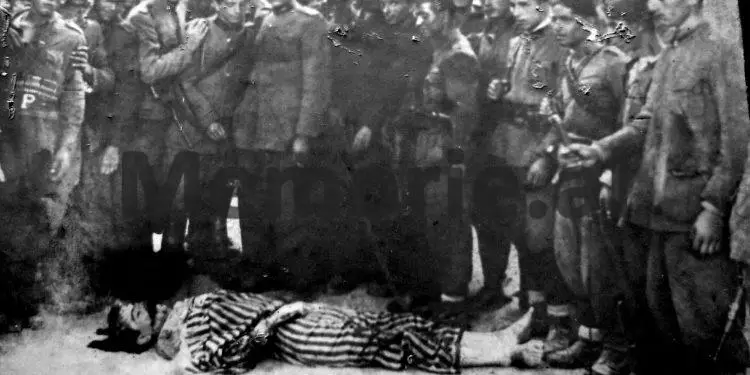

But the massacre of Tivar, April 1945, was it not based on Enver Hoxha’s agreement with the Yugoslav leadership? The young Kosovars, gathered by deception by the partisans of the native Albania, would be brought from Pristina to Prizren by the brigade commander Et’hem Gjinushi, where he would hand them over to the Serbo-Montenegrin partisans, who would immediately herd them like cattle, heading for distant Shkodra.

Exhausted by the indescribable fatigue of an extremely long journey on foot, and after having lost dozens of comrades killed for terror by the Serbo-Montenegrin partisans along the way, they, with torn clothes and often without a single thing on their feet, would finally arrive in Shkodra, like the slaves of the world, a scene that the citizens of Shkodra would watch with pain and tears in their eyes, while it was heard that the communists had said: “The Kosovar pigs have it good”!

After a short stop in Shkodra, those unfortunates, under the barrels of Serbo-Montenegrin guns, would set off for Tivar, at the entrance of which, after the powerful Slavic call; “Idu balisti” – (The ballists came) – would fall under the barrage of machine guns placed for that purpose earlier, on the upper side of the road.

It should not have happened in history that a government and a country, out of servility, gave another country “half a homeland,” with land and people, a country with which, even worse, a life of war and blood had passed, something that Enver Hoxha and his communists would accomplish without any hesitation or remorse, for which Tito would later, as a reward for their “outstanding contribution,” decorate the entire Albanian leadership with the highest titles, regardless of whether they would soon fall victim to the treacherous Enver Hoxha:

Enver Hoxha, Koçi Xoxe, Bedri Spahiu, Mehmet Shehu, Dali Ndreu, Sejfulla Malëshova, Baba Faja Martaneshi, Ymer Dishnica, Nako Spiru, Tuk Jakova and any others, whom Enver, after exchanging Tito for Stalin, and as if after the lessons taken from the latter, as we said a little above, would swallow them all like a bitch her puppies, call them traitors and spies, and ridiculously, build with their names conspiracies after conspiracies from the most imaginary, as opium for his party and for a people, who no longer spoke out of fear.

The Albanian communists, with their opportunist and conformist attitude towards Enver Hoxha’s policy, supported and legitimized his traitorous and criminal act in relation to Kosovo, and we and no one have the right to ever free them from this accusation of treason and indignation.

While these terrible events were taking place, where were those young Kosovars who had once been in Shkodra, as good students and good boys that they generally were, had made a name for themselves outside the walls of the school, and who during the War had been placed at its head? As we said before, the best of them had been treacherously disappeared by their own Serbian-Montenegrin comrades.

Emin Duraku had died in the hospital, as a result of wounds received in an ambush and had been placed on a path, through which he had been ordered by the Serbian headquarters to pass, a headquarters that was urgently summoning him for an allegedly important meeting. It is said that a few days earlier, Emini himself had said on one occasion: “It seems that the words of my father that he had told me are coming back to me, that; you are going to a wedding and, it seems to me, you are going to death”!

Zenel Hajdini, one of the oldest and bravest fighters of Kosovo, was killed in the back by his own Serbian commissar, while he was fighting against the Chetniks. Hajdar Dushi and a friend of his, who were in Kastriot, Dibra, were also urgently called by the headquarters and ordered to pass through an area that was completely controlled by the opposing forces, where they would find their death.

The Serbian partisans, comrades-in-arms of Abdulla Presheva, whose mother called them “boyfriends”, were going to poison his plate of food, which she had prepared for everyone, in which case he would be killed. Meriman Jakupi, accused by the Serbs as a traitor, would be killed behind their backs by a Serbian comrade, while he was fighting in Fushë-Aliaj of Dibra. Xheudet Doda would also end up in one of the German crematoriums, spied on by a Serb he knew.

A dim panorama of the events of Dukagjin, in its first two years under communism

To somehow complete the panorama of Shkodra with its districts for that time, it is necessary to take a look, however cursorily, at Dukagjin, where the escapees, organized in separate groups, were numerous and their encounters with the Pursuit Forces were also numerous. As in no other part of our area – not including Mirdita, to be precise – in Dukagjin the number of escapees, over time, would grow, to the point that during 1946, they would be counted in the hundreds.

When you consider the waves of the most savage terror that fell on those mountains of Dukagjin and the great sacrifices that its poor people were forced to suffer in the name of faith and free life, and on the other hand, when you are not able to properly describe the struggles that its numerous and brave escapees have waged, you feel sorry and something inside kills you. So I feel it necessary to repeat once again that I have undertaken to reflect only my experience. There will be others who, separately for each area of Shkodra, will shed sufficient light on the events and specific people of that time.

However, despite the shortcomings, I feel satisfied and it seems to me that I am fulfilling an obligation of mine, when I manage to reflect parts of the people’s resistance, wherever they have occurred and, in this case, I continue to affirm that I feel proud, every time I see that Shkodra and the mountains, have continued to share the same fate together. Dukagjini, like most of Malsia, during the War, had prevented the movement of communists through his area with “usull” (bonds of trust).

Furthermore, in connection with this, Dukagjini had also raised a defensive battalion, led by his military sons, who, in turn, had been: Major Gjergi Vata, Nikë Sokoli and Major Mark Mala. Sometime before the end of 1944, an Allied mission there, headed by the English Major Neel, had orders to do their best to hold the area without surrendering it to the communists, for a period of no less than three months, with the promise that by then the forces of their countries would land.

It was also this promise – as in Kosovo – and the blind faith in it of many mountaineers, that kept them in the mountains, constantly being killed by the Pursuit Forces, until the amnesty of 1946 was issued, in which case some of them would surrender, but that nevertheless, there would still be many of those who escaped, continuing to believe in a change in the situation on the part of the Allies, not to give up resistance through great sacrifices and real battles, although often they had only those silent mountains and hills as witnesses, and those lonely caves as their last refuge and trench.

And who were their commanders? All of them respected and brave. Such was the case with the aforementioned bajraktari of Nikaj Mërtur, Mark Tunxhi, and also Nikë Sokoli. The commander was also Major Gjon Destanisha, to whom King Zog, for his proven ability and loyalty, had awarded a special medal. Among those mountains was also Academician Palë Thani, who years earlier had graduated brilliantly in Modena, Italy, and received a gold medal. After two years of escaping into the mountains, he surrendered after the amnesty declared by the Sigurimi, as always treacherous, one day, in one of his death cells, he would be killed by the executioner Fadil Kapisyzi.

With them was also another academician, Mark Mala, as well as Academician Martin Sheldija and Captain Gjelosh Luli. Among those mountains, another son and a saint of Dukagjin, Major Gjergj Vata, a good academician, in the mountain with the symbolic nickname “Cukali”, who had encountered the Pursuit Forces several times, and who on December 7, 1946, while he was resting at a place called “Red Rock”, near the Cukali mountain, after a long and tiring journey that he had made, was killed from behind by an ambush that the Sigurimi had set there beforehand, to be sung later like this by the rhapsodist:

“On the Red Rock, by the deep stream,

They say there was once a cave,

They say there was an inn,

Where Gjergi Vata stayed as a vagabond.

Where the mountains gave him bread and bread,

Until that night that the black shadow,

As if it were grain of loneliness

killed Gjergi Vatë in the back”.

When we were in prison, we would hear about many interesting stories of escapees from Dukagjini and, sometimes, even the most terrifying, with rare acts of bravery and great pain. Among other things, I still can’t remember the name of Pjetër Mehmet Shpendi, the son of the patriot Mehmet Shpendi, about whom they told us how he was killed, after a heroic fight he had fought.

I also remember the name of a nun from Dushman, a certain Palina Palit from Dushman, who had continued to bring bread to the fugitives in the mountains for a long time and, when one day after her arrest she was brought to trial, she would not admit anything, especially as it had to do with the priest Dom Alfons Trackin, whom she had respected like no other. After the shooting of Gjelosh Lulash, implicated in the “Albanian Unity” organization, many of his close relatives had gone to the mountains, and in revenge for their Gjelosh, they had killed several partisans.

Eventually, seven men were killed from the house of Lulash Gjelosh, Shosh’s flag bearer and Gjelosh’s father. Lulash himself, whom King Zog had once sentenced to death, and later, by grace, promoted to “lieutenant of the faithful”, at the time we are talking about, was counting the last days of his life, inside a sickroom in the large prison of Shkodra. It so happened that one day, the chief of the Security, Zoi Temeli, entered the room where Lulash was suffering.

The dialogue that took place between them on that occasion would highlight two opposing worlds, the Albanian one and the communist one, represented by the criminal Zoi Themeli, as a man who was completely destroyed by the ideology and the numerous crimes he had committed up to that point, and the other, represented by the brave and courageous mountaineer, Lulash Gjeloshi, who, although with numerous wounds in his heart, in confronting him, would show himself as always, a true mountain man: strong, upright and restrained.

Lekë Harapi, sick and in the same prison cell as Lulash Gjeloshi, speaking about this case, in his book entitled “50 years of memories in the homeland and in exile”, on page 89, would write: “Mr. Temel sees Lulash Gjeloshi lying there as sick as he was and says: if you were still alive, you would take the corpse!? Yes, at least, have you repented for all that your men have done, killing our partisans?

Do you know how much they have hurt us?! And Lulash Gjeloshi, calmly, would immediately answer: ‘As for the bread, as much as your partisans have hurt you, so much more have my men hurt me, because, man, God knows how badly I have tried to raise them and today they have broken my heart and ruined the guest house. Well, as for my work, man, that work is easily enough, “Because I have lived and suffered so much for the sake of Albania, for a man of the mountains, but I know how to say, ‘Woe to those who do evil in this life!'”

Another time I would hear from Lorenc Vata, how in one case Ndreko Rino, as commander of the operation in Dukagjin, where he and Xhemal Selimi, his deputy, were one day in “Talune të Vilas”, the partisans were ordered to shoot the two brothers in front of their mother, just because they had once given bread to some fugitives. The security, in its work as cunning and treacherous as it was inhuman and criminal, when the need arose, would turn even its own servants into victims.

Even in Dukagjin, it would happen that people recruited by him under the threat of persecution, or lured for benefits, as if to squeeze them well and good, and when they no longer entered the work, that Sigurim, would not only abandon them without compensation, but would also persecute them until they disappeared, when it wanted to cover the traces of its work with them.

The Sigurim, with its refined methods, had sometimes managed to introduce into the ranks of the fugitives, people in its service, even those who were trustworthy among them. Loro Vata told again, about a certain Mark Sokol Pjetër Gjokaj from Nikaj-Mërturi, how he, introduced by the Sigurim, would gain the trust of all those Dukagjin fighters, because as a machine gunner of the company he was, he would always distinguish himself in the fighting.

Thus, continuing Loro Vata, he would also tell me about a certain Gjelosh Vata, and another named Vogël, both from the Gimajs, who were recruited by the Sigurimi and given detailed instructions by it, before they supposedly escaped, as a proof of their faith in the people, and even more so as evidence for the commander Gjon Destanisha, for whom they were headed, they would carry out the action of burning the hospital in Breg i Lumit without a second thought. Gjon Destanisha, thanks to his experience, would immediately turn them back. In return, the Sigurimi, in order to eliminate the secret they had with them, would shoot that Vogël, while Gjelosh Vata would be kept in prison, with a life sentence.

There were cases when two or three of my brothers, my acquaintances, had been imprisoned from those parts, and sometimes they would not let any male take me home, because as they themselves once said, “it would take months for anyone to come around the prisoners at home, let alone us in prison”!

I had the chance to be in a prison cell for some time, with a certain Zef Mirashi, who had previously served in the gendarmerie with the rank of aspirant, and who had himself been the third brother on the run. One of them, Deda, had been killed in the fighting with the Enemy; while Zef and Marku, after two years in the mountains, had surrendered with the amnesty announcement, only to later serve several years in prison each.

In this Zefi, who was the eldest of the brothers, with somewhat strong masculine features and bright eyes that constantly expressed patience and dignity, and who also had a strong, almost bitter voice, I would also notice a sense of security that he had in himself, whenever he spoke. From time to time it seemed to me that I was curiously reading on his face a concern that he kept secret. Or did he not also have a very serious and correct attitude!

I had the impression that in this man the maturity of the years, the duty of the soldier and the great sufferings of life, as well as his nobility from the mountains, would contain that strong and human character of his, which was also shown by the sparing words, although somewhat with strict notes that he used, as well as his attitude in general as if he were thoughtful in itself.

Like Zefi, I remember three other brothers from Shllaku, with the surname Noka, who were called Gjelosh, Cin and Gjin in turn, the latter a little older than me, and they were friends with Sami Repishti. Their voices were not heard, especially the two eldest, and if I am not mistaken, there was no one to follow them. The partisans had burned their house and killed one of their first brothers.

They had been proven in the mountains as loyal and brave men. They had grown up in a harsh nature, which had cultivated in their characters not only courage and bravery, but also a measured and reserved attitude, so much so that even if they had had heroic acts, they would never have spoken of them to others. They had received the kind of education that neither school nor years had given them, but their own, lessons as if by tradition and their own misfortune that they were suffering without feeling it.

Seeing them so wise and calm, often sitting alone on their narrow beds, made me believe that those men thought about nothing less than their sufferings and that their minds should have been at home and they were left without any of them. The stoicism with which they were facing their prison sufferings, seemed to have ennobled their words even more, which they would constantly have few and well-considered. Memorie.al