By Sali Bollati

-“To my great sorrow, I could not find the place where my relatives were buried: brothers Faruku, 5 years old, Ferhat, 13 years old, and sister Makbule, 2 years old, grandparents, mother and father”-

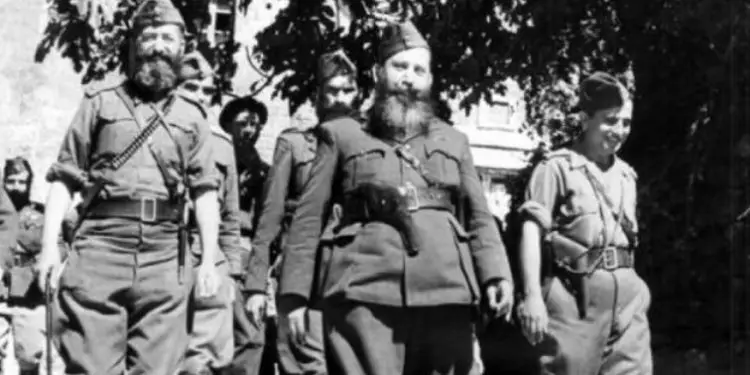

Memorie.al / 66 years, to return to his homeland where he left his mother, father, grandparents, two brothers and a sister, all killed by the Greek genocide. This is the painful story of Sali Bollati from Paramithia of Chameria. He was only 7 years old when he left Çameria and he remembers well the difficult road he traveled to arrive in Albania. Sali Bollati has returned to his hometown 66 years later, at the age of 73. He recounts with emotion the moment of returning to his land. While his account of the day of the escape is chilling. There in Çameri, he left his brothers, Faruk, 5 years old, Ferhat, 13 years old, and sister Makbule, 2 years old, killed that day by the savage hand of Greek Nazism.

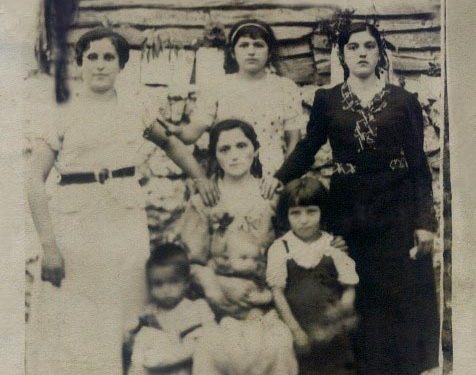

“I was only seven years old, while my wife, Bule Pronjo, 6 months old and the son of my aunt Dr. Tahsin Demi, was only 3 months old when we lost our fathers. So, I, as the eldest, still have in my mind the murders, massacres and sufferings that the Greek chauvinists inflicted on my grandfather, Muharrem, 82 years old, grandmother Rukije, 72 years old, father Ibrahim, 52, mother Betulla, 36, brothers, Faruk, 5 years old, Ferhat, 13 years old, and sister Makbule, 2 years old.

They, along with over 600 other Paramithiots, lost their lives because they were Albanians. While my sister Qerime, 10 years old and I suffered in prison, until December 1944, when we were violently expelled and the English soldiers transported us to our mother Albania. This is how I will try to show where are the lands where our parents had erected the towers and palaces, and where they were born”, Saliu confesses.

He returned to Çameri in September 2010, only with his American passport, because the Greek authorities do not allow entry visas for those Albanians who were born in Çameri. Together with his wife and cousin Tahsin Demi, they visited Çamëri in September 2010.

“After crossing the Neck of the World, with tears in our eyes, we entered the ‘Blessed Land’. The immediate impression there is the endless olive trees, and surprisingly they held more olives than leaves. We took our first vacation in Filat. Among many newly built houses you see old, half-ruined houses. There in the center, in front of the gymnasium in a beautiful flower garden was a cafe.

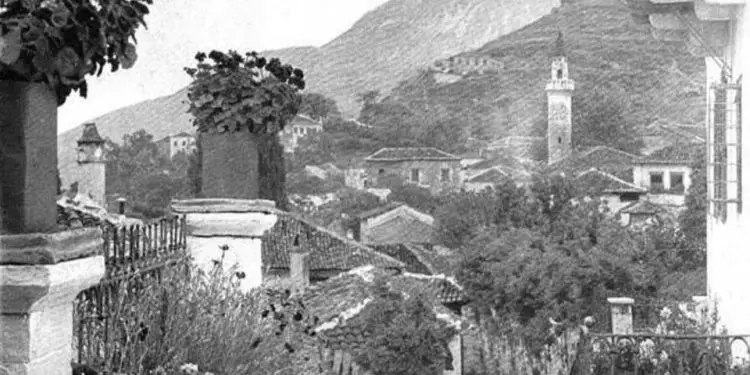

I tried to speak Albanian, but the waiter tells us that he is not local. Then we went to Paramithi. Many houses were built, but the Bollatat Tower stood at the top of the city. This medieval Tower was not only restored, but has been turned into the Paramithi Museum.

Unfortunately it was closed that day. Next to it stood the house where I was born, still inhabited today, but by illegal residents. The high stone portal of the courtyard door no longer existed. In its place, an iron door locked with a key. No one was visible.

In the meadow where we played together with our peers, Rexhepi, Mit’hat, Mihal and Jani, bushes have sprouted. While the many olive trees and figs, along with the vegetable garden that surrounded our house, lacked the care and warm hands of the past; have turned into bushes and buildings.

With Tahsin, we went to the place where he was born. I remember it was near the gymnasium dormitory. A few ruins of a thick wall were visible there, but a new house had been erected whose lady told us that she had come to Paramithi and did not know whose land it was.

All the old cemeteries near the former 9 mosques of Paramithi (the last mosque, that of Bollat was demolished in 1952 – confirms Spiro Muselimi), have been destroyed by building houses and roads.

Meanwhile, a basketball court has been laid over the pit, where the bodies of over 600 victims of the Greek genocide of June 1944 were thrown. The greatest sorrow for a living person is when he does not find the resting place of his ancestors, not being able to leave a bouquet of flowers, for the parents of the beloved who, although born and raised in their thousand-year-old houses and properties, are not allowed a grave for eternal rest. With this great sorrow, unhealed wound, we left for the second time, from our Paramithia!

We left for Parga. Parga, as a coastal city, has a strange appearance. With the houses next to each other and the cobbled streets under the beautiful medieval castle, it is crowded with people, locals and tourists. We had dinner at Grigori’s restaurant, who together with his brother, Thimion, spoke Albanian to us.

Just like the language we spoke and the food and drinks they served us, they made us forget Paramithi, the silent martyr. They are from Rrapëza, a village near Parga. Here, life does not stop until the early hours of the morning.

The next day we went up near the Castle to the so-called Turkish Bazaar; there you can hardly distinguish the shops from the houses and the people are very friendly and hospitable. Walking and talking, an old man approaches us. “I am Panua from Saint Djella (today it is called Aja Qirjaqi), a village here near Parga.

I heard you speak your language, it’s good that you came to us”. In the village, we talked all this Gluha, even with the priest that’s how we get along. Here I remembered that the Bishop of Cameria who in 1877 had translated the New Testament into Albanian, since the Cham Christians did not understand the mass in Greek.

In fact, in Chameri, as well as in other provinces, both Muslims and Christians, we were all Albanians. In fact, not only were they often brothers to each other, but they also married. When we asked Pano if he had known a Veli Manzurana here in Parga, he addressed an elderly woman in Albanian.

“My Vasilika, don’t talk to them because they want to know something.” Vasilika approached and greeted us. When we asked her, she answered with great longing: “What do you drink, I and Hysnija, the sister of Qamile, Veliu’s wife, were close friends.”

And Vasilika, tell us how in 1944, Qamileja went and took out her two youngest sisters, Feton and Dilen, from the Paramithi prison, who later married Albanians from Korça, who had just come from Australia. But poor Qamileja, continued Vasilika, always remembered her desolate brother, Nelon, whom the Greeks had killed in Paramithi and left behind a 3-month-old son.

Listening to Vasilika’s story, I was moved and I told her that this handsome doctor next to me is the 3-month-old boy who was cared for and raised by his dear and honorable mother, my aunt, Zybideja. Tahsini hugged Vasilika, and they hugged tightly, and we looked at them with tears in our eyes. And this is not a fairy tale, but a truth that cannot be forgotten.

Here we realized that; “oblivion” and silence in Paramithi, cannot be true. The memory, love and popular respect, regardless of the disappearance of the graves, remains alive and cannot be forgotten, and the time will come, that one day we will also place a bunch of flowers for the souls of our parents, who, through no fault of their own, left us orphans on the streets.

The hospitality of the parganjots was endless. Listening to the conversation, another woman opened the door and invited us: “Come in, I’ll give you a drink that I prepared myself, with good figs.”

We went in and continuing the conversation, that in the village of Rrapëz, all deaf people speak Albanian, even there are elderly people who do not understand Greek well. The phone rings, Dhimitra picks it up and says: “What do you know my Parashqevi, are you better today?”

And after finishing the phone conversation, she explained to us that it was her sister, speaking from their village. She told us a little shyly, that; how good it would be if Cham dancers and singers came here one day.

That we missed hearing our very sweet songs and, even more, seeing those brave Cham dances! We didn’t know what answer to give him. The sweet conversation in my mother’s ear lasted a little longer, after we thanked her for the love and respect she showed to us, with very tasty licorice, we left sad, but also somewhat ashamed, that we could not respond to Dhimitra’s wish for Chama songs and dances.

We went up to Ali Pasha’s Castle, as it is called today. In addition to the amazing views of the coast of Parga, in the Museum that they had built inside it, I left the note: “It was a special pleasure to see here the Albanian heritage, also represented by the well-known Parga woman, Elena Gjika or Dora D’Istria. I signed it, Sali Bollati, Paramithioti from New York”.

On the way down, a man stopped us near his shop. It started in Albanian, but immediately changed it to Greek. He tried to convince us that, in fact, we lived next to each other in friendship, as brothers, but some groups of people, in order to take the property of others, did that havoc like in Paramithi, also here in Parga.

We went down and swam in the warm and crystalline waters of Parga beach, even “competing” with each other, who would be the first to touch the big stone of the opposite island with his hand. We left the hospitable Parga, with the best impressions, for the southernmost part of Chameria.

Preveza, in the Gulf of Arta, is a city both beautiful and historic. We tried to find the Dinej’s Palaces, where in 1879, Abedin Pasha Dino and Abdyl Frashëri, addressed the Congress of Berlin, so that the Vilayet of Ioannina, together with the whole of Çamëria, should not be separated from other Albanian territories.

And this right request, including the support of the armed people, remained in force until March 1913, when the Albanian province of Cameria was occupied by Greece.

We passed by Margelliçi with many old ruined buildings, but surprisingly; there was only a minaret of a mosque and many new houses, next to it. Here, dr. Ingridi, Tahsin’s wife, told us how her grandfather, the well-known patriot Rauf Fico, had served as Kajmekan in Margelliç and later in the role of the Foreign Minister of the Albanian Kingdom, had raised and defended the issue of Chameria with dignity.

After Mazrek, full of olive groves and three oil factories, we drink coffee in Platare. We went to Gumenica, which stretches along the sea coast, where many ferries connect it with the rest of the world.

We went together with the car of Dr. Tahsini on the ferry and we headed to Corfu. After nearly two hours, looking longingly at the coast of Çameria from afar, we land in Corfu. Corfu, with its forts and characteristic buildings, is very similar to a European city.

In fact, tourists from all over Europe and the world rest there. In the restaurant where we had lunch, we were served with pleasure by a clever Albanian boy who is very dedicated to his work. The next day, while returning to Gumenica, contemplating the Cham coast again, we are approached by some Greek tourists who had come from Thessaloniki.

They ask me where we are from because they have never heard the language we speak. I tell him that I am from Paramithia and we are speaking Albanian. One of them, surprised, says that; Paramithia is located far from the border, how is it possible that you speak the Albanian language.

After explaining to them that not only Paramithia, but all of Çameria, up to Preveza, which is further south, was occupied by Greece, only in 1913, as well as your Thessaloniki, in 1919. They immediately left without saying a word. We got off the ferry and made our way back.

I couldn’t leave those parganjos who wanted to see, meet and rejoice with more Albanian brothers. They said that now that the Albanians have come for work, they feel better here. Uncle Panua even told us that: “It would be very good if a school were opened, so that our children would not forget the ear of God”! Memorie.al