By ARMAND PLAKA

Memorie.al / If you try to ask about them in Kosovo today, you will have some difficulty getting an answer. It is even possible that silence will follow and you will see faces that frown and show annoyance, but there are still many others who are willing to give you full answers, and prove that they know a lot about them. Well, we are talking about Albanians who have lived in Belgrade, in the heart of Serbia. Although it seems paradoxical, Belgrade hides a lot of Albanian evidence and traces within it, even though everything Albanian there seems to be a very small and modest presence.

Coming across an interesting material from the Albanian section (now closed, officially for financial reasons) of the well-known radio station B-92 in Belgrade, with author Naile Imami, I was excited to bring something more in an elaborate version and shed more light on the history of the first Albanian settlements there and many other aspects, known and unknown, that have to do with this fact. So, who were the first Albanians who decided to work and live deep in the land of their “problematic neighbors”?

– What difficulties did they encounter and continue to encounter during their lives there, the treatment they received over the years, the discrimination or even the appreciation they received, the changes they have undergone along the way, their integration and successes in the largest Balkan metropolis, as well as many other interesting facts and figures that best illustrate what we said above.

When does history begin?

The recorded history of Albanian settlements in Belgrade begins at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were about a hundred Albanians living in Belgrade, most of who had come there to earn a living. According to sources of the time, it appears that “the Salepçi and Bozaxhi were especially noticeable, who were dressed in Albanian national costumes.

They had a plis on their heads, wrapped in a scarf”. On the streets, one could also see, according to the renowned architectural historian Aleksandër Deroku, “groups of two or three Turks”, as they were called at the time, in their white-collared clothes, with saws and sledgehammers on their shoulders. They sawed beech wood “into four cuts, five pieces” or “into three cuts, four pieces”, as it was understood.

The Belgrade newspaper “Radničke Novine” in 1913 wrote: “We in Belgrade know Albanians as quite hard workers, who load and unload loads on the banks of the Sava and Danube rivers. They are also saw millers and there is still no Belgrader who has complained about the laziness of Albanians”. At that time, a small number of Albanians were also educated in Belgrade. Among them was Nikoll Ivanaj, along with two members of his family, Martin and Mirash Dodë Ivanaj, who were engaged in poetry in the Serbian language.

Those poems were published in 1906-1911. Among the craftsmen and merchants in Belgrade, there were several Albanians. As a wealthy merchant and a well-known person, Hajrullah Hajrullahović (Hajrullahu), owner of a Persian carpet shop located in the center of Belgrade, was especially prominent at that time. The attention of Belgraders at that time was especially attracted by his large white “Hispanosuis” automobile, which was driven by an Arab in uniform.

Two Belgrade newspapers in Albanian

In December 1900, the biweekly newspaper “Bratimstvo” (Brotherhood) began to be published in Belgrade, the name of which was also written in Albanian, in Cyrillic script. The owner of the newspaper was Aleksa Bogosavljevič – Berisha, originally from the Berisha brotherhood. During the first year of publication of this newspaper, articles were also published in Albanian (in the Cyrillic alphabet).

From 1902 to 1906, the newspaper “Albania” was published in Serbian, in the Cyrillic alphabet and in Albanian, in the Latin alphabet, in the Gheg dialect. On the cover it was written in Albanian; “Shipja e shkiptarëvet” (Albania of the Albanians). The newspaper strived for reconciliation between Serbs and Albanians and was printed in a total of 44 issues. Its owner was Jashar Erebara.

Shelter for political emigrants Belgrade became the place where, during some hot political periods in Albania, some Albanian intellectuals and politicians found shelter for a short time. When in September 1924, Zog was overthrown by the then opposing leftist liberal-nationalist groups, led by Fan Noli, Ahmet Zog with his son-in-law, Ceno Bey Kryeziu (Crnoglavič) and about 500 supporters, came to Yugoslavia. For several months, Ahmet Zog lived in Belgrade, in the “Bristol” hotel.

At the end of the following year, with the help of the Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian Kingdom, he managed to reverse the situation in Albania. After Ahmet Zog regained power, it was now the turn of a large number of his opponents to “enjoy” life in exile, which escaped and, ironically, went to Belgrade. Among them was the Catholic priest and writer Lazër Shantoja, who wrote the story; “Albanian children in the flowerbeds of the city…” (In 1925, published in 1928).

Albanians in Tito’s socialist Yugoslavia

After World War II, most Albanians in Belgrade continued to be manual laborers and carpenters, but over time they increasingly began to work in more specialized trades such as construction, especially during the 1970s and 1980s. A number of them had by then settled permanently in purchased apartments and had integrated into the life of the capital of former Titoist Yugoslavia. According to data from the Belgrade Chamber of Commerce, in 1983, for example, in the territory of this city, approximately 3% of private shops were in the hands of Albanians. Most of them were pastry shops, then bakers.

Twenty Albanians owned restaurants, and the same number had their own trucks and cars and was engaged in the transport of goods; three Albanians were also owners of car repair shops. Five goldsmiths should also be mentioned, including Mjeda and Čivlaku, who still have their well-known shops in the center of Belgrade today. Around 40 translators and other clerks worked in the Federal Executive Council, the Assembly of Yugoslavia and other administrative and service sections. After the nineties, but even before, a phenomenon was noticeable: Belgrade hospitals were full of Albanians and the medical staff “behaved well towards them”, especially towards those who “paid in German marks”.

The Kosovo War and the Albanians of Belgrade

For Albanians in Belgrade, in addition to other problems they experienced before (distrust, insults, hatred), with the arrival of Serbian refugees from Kosovo, life became even more difficult. A large number of Albanians decided to move from Belgrade, out of fear for the future. During the Kosovo war, when some Albanians left Belgrade, their homes were occupied by Serbian refugees from Kosovo, with the excuse that; “we have been persecuted by Albanians, therefore we have the right to act like this”.

July and August 1999 were the most difficult months for Albanians in Belgrade. Some of them were attacked and even physically threatened, in addition to the insults and the tense climate and anxiety they experienced daily. The windows of many Albanian shops were broken. A small group of Albanian students at the University of Belgrade was imprisoned in May 1999 on charges of having prepared “terrorist acts”.

During the main hearing, the defendants described in detail the torture they experienced during police custody, where, as they said, they were forced to confess to the crimes they were charged with using violent means. After a few months, most of them were released as innocent. After the 1999 war, more than 300 families moved out of Belgrade within a few weeks. In fact, the exodus of Albanians began in the late 1980s.

Albanology in the Serbian capital

The first scholar to seriously study the Albanian language among Serbs was Henrik Baric, a Catholic from Ragusa, who studied in Graz and Vienna. In the 1920-1921 school years, as part of the seminar on comparative grammar of Indo-European languages, he also included the “History of the Grammar of the Albanian Language”. This work of his also marks the beginning of the functioning of the field of Albanology at the University of Belgrade. The Department of Albanology in Belgrade, the Council of the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Belgrade, on May 31, 1925, decided to establish the Seminar for “Albanian Philology”, which was entrusted to Henrik Bariç. The Seminar for the Albanian language resumed its work in the 1948-49 academic years, and Vojislav Dançetović was elected as a lecturer. Anton Çeta and Idriz Ajeti were elected assistants in 1950, which had completed Romance studies at the University of Belgrade. Later, both of these names became prestigious scientists throughout the former Yugoslavia.

The Albanian “Brain” of Belgrade

Before World War II, a considerable number of Kosovo Albanians studied in Belgrade. At the University of Belgrade, Zejnel Ajdinović (Ajdini), Mehmed Barjaktarević (Meto Bajraktari), Ramiz Sadiković (Sadiku), who lost their lives as partisans in World War II and were declared “People’s Heroes”, also studied law. Also Rashić Dedović (Deda), who also lost his life as a partisan, Aziz Sulejmanović, fought as a partisan, Esad Imerović (Imer), Kurteš Agusević (Agushi): for veterinary science: Esad Mekulović (Mekuli), who in 1933-36, published social poems in progressive magazines of the time: for agronomy: Qamil Ibrahimović (Ibrahimi), for romance: Ferid Peroli: technology: Hivzi Sulejmanović (Sylejmani), after the war a famous writer, etc.

After World War II, Belgrade thus became for a long time a center where many Albanians from the territories of the former Yugoslavia studied. The first Doctors of Science from among the Albanians of Kosovo came from the University of Belgrade. Idriz Ajeti defended his dissertation in 1958 at the Faculty of Philosophy, in the field of philological sciences. At the Faculty of Natural Sciences, in 1959, Dervish Rozhaja also successfully defended his doctoral thesis in the field of biological sciences, and at that time he was the youngest Doctor of Science in Yugoslavia, and that same year, Esat Mekuli was also promoted to Doctor in the field of veterinary medicine.

Likewise, Martin Camaj, an immigrant from Albania, began to be educated in this city, who graduated in Slavic languages at the Faculty of Philosophy. Musli Mulliqi, Gjelosh Gjokaj, Engjëll Berisha, Bedri Emra, Tahir Emra, Hysni Krasniqi, Sylejman Cara were also educated in Figurative Arts, in the applied arts: Mateja Rodiqi, Rexhep Ferri and Shyqri Nimani, in the field of music: Krist Lekaj, Selim Blata, Mark and Gjergj Kaçinari, Bajar Berisha, etc. The names of the famous ones stand out in particular: Bekim Fehmiu, and also Faruk Begolli, Enver Petrovci, Xhevdet Qorraj, in theater and cinematography and also in directing: Isa Qosja, Selami Taraku, Emin Halili, Artan Skënderi, dramaturgy: Ekrem Kryeziu, Petrit Imami, etc.

STREETS WITH ALBANIAN NAMES IN BELGRADE

It seems paradoxical, but many streets in Belgrade bear Albanian names for various reasons. They mainly refer to the history of the “sporadic contribution” of some Albanian who “brought water to the mill” of Serbia. “Skenderbegova ulica” (“Skanderbeg Street”) is located in the part of the city that has been there since 1896. One of the oldest streets in the center of Belgrade, “Makedonskaulica”, from 1872 to 1896, was called “Kastriotova ulica” (“Kastriot Street”), at a time when it was thought to be of Serbian origin. “Kondina ulica” (“Konda Street”) is named after an Orthodox Albanian from Southern Albania, who showed great bravery in 1806, when Belgrade was liberated from the Turks.

This street in the center of Belgrade has been named after him since 1872. “Esad-pašina ulica” (“Esad Pasha Street”) was named after this controversial politician for his role in Albania, in recognition of the help he gave the Serbian army during its retreat through Albania. “Ulica Ramiza Sadiku” (“Ramiz Sadiku Street”) was named after this revolutionary and communist from Kosovo, who was declared a “People’s Hero” after the War. The street is located in “New Belgrade”, near the banks of the Sava River, in the former working-class neighborhood, today not far from the most luxurious hotels in Belgrade such as: “Hajat” and “Intercontinental”.

“Skadarska ulica” (“Shkodra Street”) is considered one of the most attractive streets in Belgrade, with several old and very popular cafes, and it was given this name in 1872. This street and part of the city is also known as “Skadarlija”. A small street in Zemun, the walled province of Belgrade, is also known by the same name. There is even a street in Belgrade known as “Albanska ulica” (“Albanian Street”), which is located in one of the oldest municipalities of Belgrade, in Palilula. It was given this name in 1927, and it had it until 1972, when it was changed to “Ulica Albanske spomenice” (“Albanian Memorial Street”). But (at least in Albania), let no one think that they gave it this name because of their love for Albania and Albanians.

It is connected with the dark memories and suffering of Serbian soldiers, who retreated in very difficult conditions through Albania in 1915. We also encounter a series of street names such as; “Dracka ulica” (“Durres Street”), “Lješka ulica” (“Lezha Street”), which is located in the Municipality of Çukarica, and which received this name in 1930, for the same reasons that have to do with the soldiers of the Serbian army in 1912, when on November 18, they “liberated” this city from the Turks, and when in 1915, through the narrow streets of this city, many exhausted Serbian soldiers and civilians passed, retreating before the Austro-Hungarian army.

“Palata Albanija” (“Palace of Albania”) is located in the center of Belgrade, where before World War I, there was the “Albanija” cafe, a name given by the owner in honor of the Serbian fighters who fought in Albania in 1912-1913. It was built in 1939 and was the tallest building at that time in Yugoslavia, which they called “Palace of Albania”, after the cafe in question, and by this name Belgraders call it to this day.

THE “FAMOUS” ALBANIANS OF BELGRADE

Many well-known figures to all residents of the capital of Serbia and the former Yugoslavia have lived in Belgrade. Politicians have lived there: Mehmet Hoxha, Ismet Shaqiri, Alush Gashi (his niece is a well-known RTV B-92 journalist, Antigona Andonov), Ali Shukria, Sinan Hasani, Kol Shiroka, Hadije Morina with her husband Murat Morina, Sokol Nimani, director of the Reserve Fund, with his wife Antigona Nimani, translator and announcer.

Ambassadors Elhami Nimani, Rexhep Xhiha, Xhavit Emini, Gjon Shiroka, Mesud Besniku, Colonel Shkreli, writer Elhami Nimani, who died after a shocking event in 1998, translator and writer Sitki Imami, journalists Hilmi Thaçi, correspondent for “Rilindja” and Masar Murtezai, editor of Albanian-language programs on TV Belgrade (1968-74), later chief of staff of Fadil Hoxha and Sinan Hasani.

Likewise, many other figures from the fields of military, medicine, culture, sports, etc. have been well-known. The name of Petrit Fejzullahu stands out, a prominent handball player in the elite club “Crvena Zvezda” and in the representative team of Yugoslavia; also Fahri Musliu, a journalist who was once a correspondent for “Rilindja”, today for “Voice of America”, Petrit Imami, a professor of film script at the Faculty of Drama in Belgrade, who in 2000 published the study book “Serbs and Albanians through the Ages” (“Srbi i Albanci kroz vekove”).

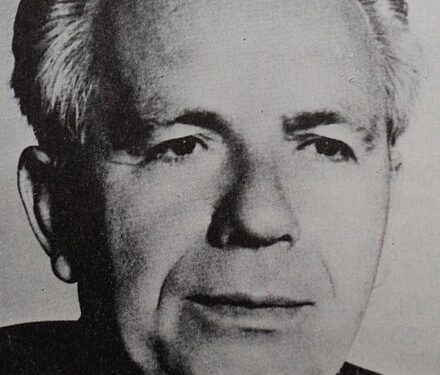

Undoubtedly the most well-known among the Albanians of Belgrade is the famous actor, Bekim Fehmiu. He achieved world fame in the Yugoslav film “The Feather Collectors”, which in 1967 made a name for itself at the Cannes Film Festival. In Belgrade he published the first part of his memoirs; “Shklqimi dhe termeri”, where he attractively describes his childhood in Prizren. Also very well-known is another actor, Enver Petrovci. During the 80s, one of the most popular pop music singers was Zana Nimani. Even though she no longer lives in Belgrade, her songs are still well heard and known to this day. / Memorie.al