Part Five

Memorie.al / The War Diaries of the Supreme Command of the German Armed Forces (Kriegstagebuch des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, KTB OKW), in the years 1940-1945, were kept by the National Defense Office at the Operations Headquarters of the German Armed Forces (Abteilung Landesverteidigung im Wehrmachtführungsstabamt). These war diaries describe strategies, battles, troop movements, front lines, objectives, operational decisions and war plans and assessments of combat situations, by the highest leadership of the German military forces. The Secretary of the War Diaries at the Supreme Command of the German Armed Forces was Helmuth Greiner until March 1943 and then Percy Ernst Schramm. In the years 1961-1965 the war diaries were compiled by historians and published by the publishing house Bernard & Graefe Verlag für Wehrëesen, Frankfurt am Main. The main historian was Percy Ernst Schramm and his assistant historians, respectively according to the volumes, were as follows:

Continued from the previous issue

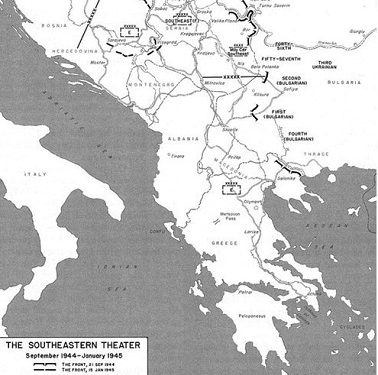

War Developments in the Southeast (01.01.1944 – 31.03.1944) The Southeast as part of the general theater of war. A look back at 1943

Page 603. The third front in the southeast area, the Albanian-Montenegrin-Dalmatian coast, did not pose a great danger, at a time when the Italian lands on the other side of the coast were all in the hands of the Axis powers. However, the very small density of the road network, the almost complete absence of railways, the state of the water supply, etc., will make it difficult for the enemy forces to advance and will give our commands time to take the necessary measures.

Page 604. After the fall of Mussolini’s government in Italy on 25.07.1943, the “Achse” plan (previously called “Alarich”, for Italy and “Constantine”, for the Balkans) was implemented on that occasion: intervention in Italy and the south-eastern area, disarming the Italians and taking over the defense of the areas previously held by the Italians in Croatia, Montenegro, Albania and Greece.

Page 605. A part of the Italian troops went over to the side of the insurgents, especially after the news was given that Italy was no longer fighting on the side of Germany, and they held a large part of the Dalmatian-Montenegrin-Albanian coast under control.

Pages 606-607. Hitler emphasized in the last days of December 1943 that he anticipated an enemy attack in the Balkan area, especially on the side of the Dalmatian-Montenegrin-Albanian coast.

Distribution of forces in early 1944

Page 611. There were two German military units in Albania: near the coast, west of Berat, was the 100th Rifle Division and in the area of Crna [Montenegro – ed. note] the 297th Infantry Division, both under the command of the XXIth Army Corps.

Analysis and measures against an Allied landing at Nettuno, Italy (22.01.1944)

Page 613. …. Allied landing operations are possible, firstly on the western coast of the Balkans, from Arta to the south of Split and secondly, across the Aegean Sea, towards Salonika. In that case, Turkey would abandon its neutrality or, even if Operation “Gertrude” [the invasion of Turkey by the German army – ed.] were implemented, the Allies would land on the western coast of the Balkans.

Reorganization of SS units

Pages 623-624. On 02.03.1944, the High Command Southeast was informed that it was being given tactical command over the 18th SS Motorized Infantry Division “Horst Wessel”, including the troops of the deputy general command of the XVIIth Army Corps. Until further notice, this Division was allowed to be used only for security duties within the region where it was located. The same applied to the SS Division “Skanderbeg”, which, as the High Command Southeast was informed on 12.03.1944, would be formed from Albanian troops, located in the XIIIth Bosnian SS Division and Albanian militia troops.

Serbia and Mihalović in the winter of 1943-1944

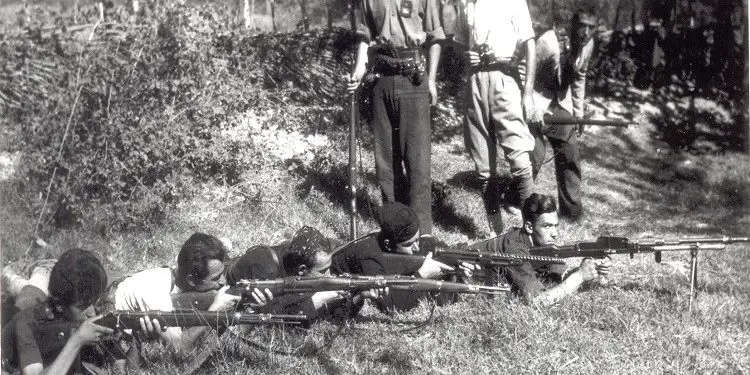

Page 639. In Albania, too, there were initially suitable conditions for the unification of anti-communist forces and the establishment of militia units, in accordance with the plan by Hermann Neubacher. The driving force in that direction was the pro-German Minister, Xhafer Deva. In cooperation with him, the establishment of a state enforcement apparatus began in January 1944. It was initially about supporting the four infantry battalions that were already in action and the occupying forces would help them by providing weapons, equipment, training and supervisory personnel.

In addition, preparations were to be made to unite all the units that were under the leadership of tribal chiefs or leaders into a national army. The leadership was in the hands of a senior SS and the commander-in-chief of the police in Albania, Major General and Brigade Commander, SS, Josef Fitzthum, who was ostensibly an advisor to the Albanian Secretary of State for national security. The operational command of the Albanian military units mentioned above, in all matters of military action, location and time of action of the troops, was in the hands of the General Command of the XXI Army Corps in Tirana.

Then there was also the position of the German plenipotentiary general, first General Theodore Geib and then General Otto Gullmann, who initially had the task of exercising their influence over the Albanian authorities (for which the German Foreign Ministry demanded the greatest possible independence) according to the instructions of the South-Eastern High Command.

The staff of the German plenipotentiary general was reduced in the period late 1943 – early 1944; For some time, the idea of a merger was considered, with the command of the general of the XXI Army Corps, but it was not pursued further. The coexistence of these different commands, to which was added the plenipotentiary of the German Foreign Ministry [Hermann Neubacher], created, just as in Croatia, great difficulties.

All these measures were made difficult, just as in Montenegro, by the difficult economic situation and the poor food supply. The preventive measures of the German authorities, primarily of the envoy Hermann Neubacher, against rising prices and inflation, were only partially successful. In March-April 1944, both countries were threatened by famine. Envoy Hermann Neubacher tried to help through the German army and, among other things, requested the sending of 120 trucks.

Since they could only be sent piecemeal, the German Supreme Command allowed the South-Eastern Command to help with its own resources; the idea was that the South-Eastern Command, in areas where the civilian population could not be supplied through the local administration, would take over not only the supply, but also the responsibility for those areas, of course in close cooperation with the envoy Hermann Neubacher.

Fighting in the winter and spring months

Page 647. On 13.02.1944, the South-Eastern Command received the order for the 100th Rifle Division, which served to protect the Albanian coast, to leave there quickly, to protect the railway, in the Bitola-Skopje region.

Page 654. When it was not yet clear how the Anglo-Americans would conduct the fighting after they had occupied Italy, the German command was widely concerned with the possibility of an enemy landing on the western side of the Balkan Peninsula, starting from Italy.

Therefore, it tried to control the ports and islands of the Dalmatian-Montenegrin-Albanian-Greek coast as soon as possible. Which they achieved in most cases in the autumn months of 1943. In the aforementioned coastal area, which could be threatened by an Allied landing, it was thought that bandit troops, numbering about 20,000, were operating.

“White” and “Red” in Greece

Pages 669-670. While the German army’s attention in the summer of 1944 was focused on Croatia, the military forces in Greece were few in number, with the main task being coastal defense and mopping-up operations in the surrounding areas. …. The Greek resistance movements never developed into large-scale operations, as happened with Tito and his three offensives in Serbia.

They were very closely tied to the region where they had power and influence. While ELAS [communist forces – ed.] had influence in most of the Peloponnese, in Boeotia, Thessaly-Thrace, (their headquarters were in Verna south of Edessa) and deep into Epirus; EDES [non-communist forces – ed.] was limited to the north of the Gulf of Arta, as far as Parga.

With the leader of the EDES forces, Colonel Zerva, and according to the plan of the special envoy, Hermann Neubacher, the XXII Mountain Corps, in the autumn of 1943, made a general armistice agreement, which was respected until July 1944. On the other hand, the agreements with the ELAS forces were only specific and country-specific.

Since the relations between the Greek resistance groups, constantly changed (ELAS and EDES went through short-term and isolated agreements), the German leadership had more opportunities to intervene to eliminate one side and prevent a joint operation between them.

The fight against the insurgents in the southeastern direction during the general offensive of the Allies and the withdrawal of German troops

Page 670. The Southeastern High Command announced on 21.06.1944 that it did not expect any frontal attack in the Peloponnese or in the region of the islands of Crete and Rhodes. However, small local attacks in the northwestern area of Greece and Albania were to be expected.

Pages 671-672. On 05.06.1944, the 1st Mountain Division began Operation “Gemsbock” (‘Wild Goat’) in the border area between Albania and Greece, starting from Macedonia. After setting up a blocking line on the border, starting from the lakes, it was to advance in a southwesterly direction, towards the coast. In this area, after the departure of the 100th Rifle Division, as the South-Eastern High Command emphasizes, on 17.05.1944, banditry, supported by the British, has increased excessively and has reached a high level of danger.

The South-Eastern Command further announces that, with the exception of a narrow area on the coast and some support points along the Korça-Ioannina road, there is a vanguard of an enemy landing force in that area, which should be taken very seriously also because of the proximity to Bari, Brindisi and Taranto, which created the possibility of a sudden landing and that Corfu was seriously threatened by enemy attacks.

The Southeastern Command had foreseen for that clearing operation, the 4th SS Division, of the Motorized Infantry of the border police, but the German army command staff did not agree with that decision, since that Division, as the only motorized unit, should not be involved in the fight with the gangs, but rather should be kept ready where it was (in Thessaly), as a motorized reserve; “with an eye on the coast”.

The advance of the 1st Mountain Division encountered strong resistance from the insurgent forces, who were well armed. As in the “Rösselsprung” operation [on 25.05.1944 – 06.06.1944 for the capture of Tito, in Drvar, Croatia – ed.] the Anglo-American forces bombed, starting from Italian airports, thus seriously interfering in the fighting.

On 12.06.1944, the 1st Mountain Division reached the coast and turned south towards the security line, previously established on the border. As a result of the operation, the Southeastern High Command announced on 25.06.1944, the enemy had suffered heavy losses and in the area of southern Albania, freedom of operational movement was guaranteed for the time being.

Pages 672-673. In the area of northern Albania, fierce fighting took place in the second half of July 1944 between the “Skanderbeg” Division (created by Albanian forces, initially part of the 13th SS Mountain Division “Hanjhar”), which had been there since May 1944, and the communist forces, which are not discussed in detail here. This Division had difficult battles here (see Situation Book on 24.07, 25.07, 28.07.1944).

In the armaments and fighting style of the communist troops, progress was noted in the unification of separate communist groups and their close connection with Tito. Towards the end of the month, this Division encountered a new attack by communists on the Albanian-Montenegrin border, who were trying to enter southern Serbia (see Situation Book on 28.07.1944). At that time, the Division received the order (operation “Draufgänger”), to create a preparatory area for a subsequent major offensive, starting from the region west of Peja, to attack in the direction of Berane.

In the fighting against Tito’s organized forces, the center of gravity, despite the heavy losses suffered by Tito’s movement in April and the first half of May 1944, was again in the border area of Serbia and Montenegro, as well as in Montenegro itself. The Southeastern High Command noted on May 17, 1944, that Montenegro, instead of being an isolated part between Croatia and Albania, was in danger of becoming a powerful area of red power. The second communist army corps had managed to maintain its striking power here, thus becoming a gathering point for bandit troops that had been hit and weakened in other regions.

Apparently, the “red leadership” intends to refresh the troops in Montenegro and launch a new offensive in the direction of Serbia. In the last days of May 1944, while Operation Rösselsprung was being carried out in Bosnia, powerful communist forces attempted to enter Serbia from the south-eastern part of the Serbian-Montenegrin border (Situation Book 30.05.1944). In early June, troops were massed in the north-east of Montenegro, under the command of General Leeb [Helge Auleb? – ed. note] to seize airports and places where gangs could enter. (Situation Book 06.06.1944).

At the end of June, a plan was drawn up to undertake another purge operation, in which the Albanian SS Division “Skanderbeg” would participate, together with mountain forces and SS police (Situation Book 20.06.1944). The operation ended on 30.06.1944, without having managed to destroy the assembled enemy forces, which were trying to enter southern Serbia, (Situation Book 01.07.1944).

Page 674. The Greek nationalist General Zervas, who had made an agreement to remain neutral with the Germans, suddenly attacked the German forces, on 05.07.1944, on the Preveza-Agrinio line. It is thought that he did this, perhaps under the instigation of the British, but the possibility cannot be ruled out that he did it simply for his own interest. ……

In a summary of the assessment of the situation on 12.07.1944, the South-Eastern Command emphasizes that; there is a possibility of a connection between the revival of Zerva’s forces and the intentions of the Anglo-American landing in western Greece, or in southern Albania, and he called in this matter, the destruction of Zerva’s troops, as a very important task. Memorie.al

Continues next issue